Mediatization, Marketization and Non-Profits: a Comparative Case Study of Community Foundations in the UK and Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gemeindebrief August 2015 Beratung Alten- Und Krankenpflege Palliativpflege Betreuungsdienste Und Alltagshilfen

Gemeindebrief August 2015 Beratung Alten- und Krankenpflege Palliativpflege Betreuungsdienste und Alltagshilfen Häusliche Pflege Kirchlicher Pflegedienst Breckerfeld Martin-Luther-Weg 3 58339 Breckerfeld Tel. 0 23 38 - 91 29 26 www.diakonie-mark-ruhr.de 2 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, Seite Inhalt vor Ihnen liegt die neue Ausgabe unseres Gemeindebriefes. Ein Großteil 4 An(ge)dacht der Artikel steht unter dem Thema: 5 Notfallseelsorge Breckerfeld „Gemeinsam auf dem Weg“. Einige Gemeindegruppen waren in den 7 Forum-Flüchtlinge letzten Monaten auf Freizeiten und 8 Kirchenmusiktage 2015 Studienreisen unterwegs, andere bewegen sich in besonderer Weise 10 Senioren-Freizeit auf andere zu (Forum Flüchtlinge, 11 Altenzentrum St. Jakobus Notfallseelsorge) oder begegnen ei- nander neu (Stadtfest). Begegnungen 12 Abendmahls-Andacht bereichern uns, gemeinsame Wege 13 Gottesdienste schaffen Verbundenheit. Wir hoffen, Ihnen mit diesem Brief 14 Lebendige Gemeinde einen guten und aktuellen Einblick 18 Wir sind für Sie da in das Leben Ihrer Jakobus-Kirchen- gemeinde zu geben. Vielleicht bietet 19 Ein neuer Anfang Ihnen der eine oder andere Bericht 20 Kinder-Kirchentag eine Anregung, den persönlichen Kontakt zu Ihrer Kirchengemeinde 21 Breckerfelder Stadtfest neu oder wieder zu suchen. Wir freuen 22 Segeln auf dem Ijsselmeer uns darauf. Sie können uns auch gerne schreiben, 24 Ein Vormittag im Kindergarten wie Ihnen der Gemeindebrief gefällt, 26 Israelreise was Sie evtl. vermissen und wie wir unsere Arbeit noch besser machen 27 Nachrichten aus der Gemeinde können: [email protected] 29 Freud und Leid Ihre Gemeindebriefredaktion IMPRESSUM Redaktion: Renate Bergmann, Jörg Bielau, Paul-Gerhard Diehl (V.i.S.d.P.), Christina Görsch, Ursula Kistermann-Neugebauer, Gunter Urban, Christof Wippermann. -

Cesifo Working Paper No. 4452 Category 5: Economics of Education October 2013

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Cantoni, Davide; Yuchtman, Noam Working Paper Medieval Universities, Legal Institutions, and the Commercial Revolution CESifo Working Paper, No. 4452 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Cantoni, Davide; Yuchtman, Noam (2013) : Medieval Universities, Legal Institutions, and the Commercial Revolution, CESifo Working Paper, No. 4452, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/89752 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

University of Groningen Die Niederdeutschen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Die niederdeutschen Mundarten des südwestfälischen Raumes Breckerfeld - Hagen - Iserlohn Brandes, Friedrich Ludwig IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2011 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Brandes, F. L. (2011). Die niederdeutschen Mundarten des südwestfälischen Raumes Breckerfeld - Hagen - Iserlohn. Groningen: s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 - 348 - Verzeichnis der benutzten Literatur Die Siglen zu den häufig zitierten Werken der benutzten Literatur finden sich auf S. 2f. Almeida, Antonio / Braun, Angelika, Probleme der phonetischen Transkription. In: HSK 1.1, 1982, 597-615 Ammon, Ulrich, Dialekt, soziale Ungleichheit und Schule. -

The Path to the FAIR HANSA FAIR for More Than 600 Years, a Unique Network HANSA of Merchants Existed in Northern Europe

The path to the FAIR HANSA FAIR For more than 600 years, a unique network HANSA of merchants existed in Northern Europe. The cooperation of this consortium of merchants for the promotion of their foreign trade gave rise to an association of cities, to which around 200 coastal and inland cities belonged in the course of time. The Hanseatic League in the Middle Ages These cities were located in an area that today encom- passes seven European countries: from the Dutch Zui- derzee in the west to Baltic Estonia in the east, and from Sweden‘s Visby / Gotland in the north to the Cologne- Erfurt-Wroclaw-Krakow perimeter in the south. From this base, the Hanseatic traders developed a strong economic in uence, which during the 16th century extended from Portugal to Russia and from Scandinavia to Italy, an area that now includes 20 European states. Honest merchants – Fair Trade? Merchants, who often shared family ties to each other, were not always fair to producers and craftsmen. There is ample evidence of routine fraud and young traders in far- ung posts who led dissolute lives. It has also been proven that slave labor was used. ̇ ̆ Trading was conducted with goods that were typically regional, and sometimes with luxury goods: for example, wax and furs from Novgorod, cloth, silver, metal goods, salt, herrings and Chronology: grain from Hanseatic cities such as Lübeck, Münster or Dortmund 12th–14th Century - “Kaufmannshanse”. Establishment of Hanseatic trading posts (Hanseatic kontors) with common privi- leges for Low German merchants 14th–17th Century - “Städtehanse”. Cooperation between the Hanseatic cit- ies to defend their trade privileges and Merchants from di erent cities in di erent enforce common interests, especially at countries formed convoys and partnerships. -

FOUNDED on VALUES Die Anfänge Der Hanse Liegen Im 12

WERTE ALS FUNDAMENT FOUNDED ON VALUES Die Anfänge der Hanse liegen im 12. Jahrhundert. Sie entstand als Bund von Kaufleuten, die ihr Handeln an gemeinsamen wirtschaftsethischen Grundsätzen ausrichteten, feste Regeln dafür schufen und so im Geschäftsverkehr schnell und sicher miteinander umgehen konnten. Das Wort des Kaufmanns zählte, Geschäfte wurden mit Handschlag vereinbart, die Erfüllung durch die auferlegten Regeln gewährleistet. Aus dieser Kaufmannshanse entwickelte sich eine Städtehanse, die in ihrer größten Ausdehnung fast mehr als 200 See- und Binnenstädte Europas zusammenschloss und neben den wirtschaftlichen auch politische Interessen ihrer Mitglieder vertrat. Der im Sommer 2013 gegründete Wirtschaftsbund Hanse folgt der ursprünglichen Tradition der Kaufmannshanse. Hier schließen sich Unternehmen zusammen, um die alten Werte wieder verstärkt in den Geschäftsverkehr zu tragen. Das Ziel: Durch eine gemeinsame Werte-Grundlage die Zusammenarbeit über Grenzen hinweg zu fördern, vertragliche und regulatorische Hürden zu verringern und Unternehmen mehr Freiraum für ihr Geschäft zu geben. The origins of the Hanseatic League, or Hanse, date back to the 12th century. The League developed as a confederation of merchants who were guided by common business ethics and who created firm principles for fast and reliable business relations. The merchant‘s word was trusted, transactions were agreed by handshake and the self-imposed rules guaranteed that all parties would meet their obligations. 200 years later a Hanseatic League of Cities has emerged from the Hanseatic League of Merchants which once comprised more than 200 European seaports and non-coastal cities and looked after both the economic and political interests of its members. The Business Hanse founded in the summer of 2013 follows the original tradition of the Hanseatic League of Merchants. -

Hagen - Iserlohn Brandes, Friedrich Ludwig

University of Groningen Die niederdeutschen Mundarten des südwestfälischen Raumes Breckerfeld - Hagen - Iserlohn Brandes, Friedrich Ludwig IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2011 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Brandes, F. L. (2011). Die niederdeutschen Mundarten des südwestfälischen Raumes Breckerfeld - Hagen - Iserlohn. [s.n.]. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 29-09-2021 - 348 - Verzeichnis der benutzten Literatur Die Siglen zu den häufig zitierten Werken der benutzten Literatur finden sich auf S. -

D a T E N B L a T T

D a t e n b l a t t Name Vorname Baumann Klaus Ausgeübter Beruf Bürgermeister Beraterverträge --- Mitgliedschaften in Aufsichtsräten und anderen Kontrollgremien i. S. d. § 125 Absatz 1 Satz 3 des Aktiengesetzes • EN-Agentur – Mitglied der Gesellschafterversammlung • WLV GmbH, Münster inkl. Ardey Verlag GmbH, Münster und Kulturstiftung Westfalen-Lippe gGmbH, Münster – Mitglied des Aufsichtsrates • Westfälische Provinzial Versicherung AG, Münster - Mitglied des Aufsichtsrates • KEB Holding AG – Mitglied des Aufsichtsrates • Gebau Wohnen eG – Vorsitzender des Aufsichtsrates • Gebau Immobilien AG – Vorsitzender des Aufsichtsrates • ENERVIE – Mitglied des kommunalen Beirates Mitgliedschaft in Organen von verselbstständigten Aufgabenbereichen in öffentlich-rechtlicher oder privatrechtlicher Form der in § 1 Absatz 1 und 2 des Landesorganisationsgesetzes ge- nannten Behörden und Einrichtungen • VHS-Zweckverband Ennepe-Ruhr-Süd – stellv. Verbandsvorsteher • Zweckverband Gewerbegebiet Breckerfeld – Vorsitzender der Verbandsversammlung • Sparkassenzweckverband Ennepetal-Breckerfeld – Verbandsvorsteher der Zweckverbandsver- sammlung • Sparkasse Ennepetal-Breckerfeld – Vorsitzender des Risikoausschusses, Mitglied im Verwal- tungsrat und im Hauptausschuss • Verband der Hauptgemeindebeamten • Verbandsausschuss des Zweckverbandes Südwestfälisches Studieninstitut für kommunale Ver- waltung – Mitglied im Prüfungsausschuss für die Laufbahn des gehobenen bautechnischen Dienstes sowie für die Prüfung/Zwischenprüfung zum Ausbildungsberuf Verwaltungsfachange- -

Hansestadt Breckerfeld Informationen Für Neubürger Und Gäste Modernes Altenzentrum Mit Tagespflege Und Service-Wohnungen

Hansestadt Breckerfeld Informationen für Neubürger und Gäste Modernes Altenzentrum mit Tagespflege und Service-Wohnungen Wohnen im Alter | Kurzzeitpflege | Ta gespflege Alten- & Krankenpflege | Betreuungsdienste Dauerpflege | Hausnotruf | Betreutes Wohnen Senioren-Cafés | Mittagstisch Eigenes Kuratorium für Pflegedienst und Altenzentrum Qualitätssicherungspflege | Demenz-Gruppe Palliativ-Pflege | 24-Stunden-Pflege Kirchlicher Pflegedienst Breckerfeld Mit einem Te l. 02338 912926 Altenzentrum St. Jakobus Tagespflege Hansering guten Te l. 02338 9193-0 Gefühl www.diakonie-mark-ruhr.de zu Hause. Wir sind da. In Breckerfeld. Wo die Menschen uns brauchen. Grußwort 1 Liebe Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, liebe Neubürger, liebe Gäste! Die folgenden Seiten sollen Ihnen ein Ratgeber sein, sich in unse rer Hansestadt Breckerfeld, die sich bei allem Respekt vor der Tradition ständig weiterentwickelt, besser zurechtzufinden. Sie erhalten wissenswerte Daten über Zahlen und Fakten sowie einen Überblick über Handel, Gewerbe und Industrie, Bildung, Kultur und Unterhaltung, Schule, Kirche sowie Sport, Politik, Frei zeit und Erholung. Breckerfeld ist eine Kleinstadt mit großer Fläche und einer langen Geschichte. Bürgerengagement und soziales Verantwortungs bewusstsein prägen das Leben in unserer liebenswerten Hanse stadt und eine rege Vereins und Festkultur führt dazu, dass man sich hier schnell heimisch fühlen kann. Hier kennt nicht jeder jeden, aber vermutlich jeden Zweiten, was dazu führt, dass sich vieles auf kurzem Wege erledigen lässt und man schnell Hilfe für die kleinen Dinge des Alltags bekommt. Ich darf Sie herzlich einladen, sich in Politik und Gesellschaft Bedanken möchte ich mich bei denen, die mit ihrer Anzeige die unserer Kommune einzubringen und von dem vielfältigen Ange Herausgabe der Bürgerinformationsbroschüre ermöglicht haben. bot Gebrauch zu machen. Scheuen Sie sich nicht, in den zahlrei chen Vereinen mit neuen Ideen und frischem Schwung – vielleicht Ich wünsche mir, dass Sie sich in Breckerfeld wohl und heimisch sogar aktiv – mitzumachen. -

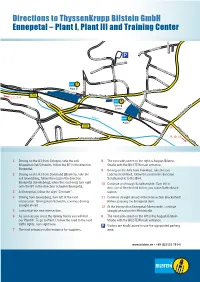

Directions to Thyssenkrupp Bilstein Gmbh Ennepetal

Directions to ThyssenKrupp Bilstein GmbH Ennepetal – Plant I, Plant III and Training Center ße ra er Straße St er Brink str. ch Brink o H P eddinghausstraße aße Gartenstr Friedrich-Asbeck-Str aße Gar tenstr e Schmiedestr aß aße aße Hochstr Vom-Hofe-Str Lohm g a tstraße nn Gar Klüter st ra aß tenstraße ß e e Höhlenstraße Plant III Höhlenstr Hohlwe Am aße aße Milsper. Str 6 r t S L702 Milsper Str - aße n n 1, 2, 3, 4 Neustr a tm Mittelstr p u Quer 7 a aße H straße aße rt- a rh Gasstr Training e aße G aße 5 Wehr Center straße Voer 8 Mittelstr der Str aße Loher Str aße Ennepe Aug ust -Bils tei n-S Plant I traße L702 12 Mittelstr Vereinsstr F Neustr elsenstr aße Voer aße er Str der Str aße aße L699 aße aße 9, 10, 11 Esbeck aße Schemmstraße Neustr 1 Driving on the A1 from Cologne, take the exit 8 The next side-street on the right is August-Bilstein- Wuppertal-Ost/Schwelm, follow the B7 in the direction Straße with the BILSTEIN main entrance. Ennepetal. 9 Driving on the A45 from Frankfurt, take the exit 2 Driving on the A1 from Dortmund (Bremen), take the Lüdenscheid-Nord, follow the road in the direction exit Gevelsberg, follow the road in the direction Schalksmühle to the B54. Ennepetal (Gevelsberg), when the road ends turn right 10 Continue on through Schalksmühle. Turn left in onto the B7 in the direction Schwelm/Ennepetal. direction of Breckerfeld before you reach Dahlerbrück 3 At Ennepetal, follow the sign “Zentrum”. -

Ratings Affirmed on Various German Savings Banks, Helaba, and Dekabank on Capital Strengthening and Integration

Ratings Affirmed On Various German Savings Banks, Helaba, And DekaBank On Capital Strengthening And Integration Primary Credit Analyst: Bernd Ackermann, Frankfurt (49) 69-33-999-153; [email protected] Secondary Contact: Harm Semder, Frankfurt (49) 69-33-999-158; [email protected] OVERVIEW • German savings banks are continuing to strengthen their capitalization despite earnings pressure from ultra-low interest rates. • They are also benefitting from sound economic conditions in Germany, leading to low credit losses and a strong inflow of stable retail deposits. • We are affirming our ratings on members of regional subgroups of savings banks in Westphalia-Lippe, and in Hesse and Thuringia including the central bank Landesbank Hessen-Thueringen, and on DekaBank Deutsche Girozentrale. • The outlook on DekaBank remains positive, reflecting the potential for stronger integration into the German savings banks. The outlooks on the other entities are stable. FRANKFURT (S&P Global Ratings) Aug. 19, 2016--S&P Global Ratings today affirmed its ratings on two regional subgroups of Germany's savings banks sector, including their central bank, and on DekaBank Deutsche Girozentrale, the sector's investment product and securities services provider. The outlooks on these banks remain unchanged. The affirmations follow our regular surveillance reviews of these entities in light of the recent publication of aggregate financial data by German regional and national savings banks associations. Specifically, we took the following actions: WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT AUGUST 19, 2016 1 1696704 | 300027913 Ratings Affirmed On Various German Savings Banks, Helaba, And DekaBank On Capital Strengthening And Integration • We affirmed the 'A+/A-1' long- and short-term credit ratings on 68 savings banks in Westphalia-Lippe (collectively Savings Banks Westphalia-Lippe; SWL). -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND. -

Amtsblatt Amtsblatt

Amtsblatt für den Regierungsbezirk Münster Herausgeber: Bezirksregierung Münster Münster, den 6. April 2018 Nummer 14 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS C: Rechtsvorschriften und BekanntmachungenINHALTSVERZEICHNIS anderer 72 Bekanntmachung des Haushaltsbeschlusses des Behörden und Dienststellen 101 Deichverbandes Bislich-Landesgrenze für das 71 Frühzeitige Information der Öffentlichkeit gemäß Haushaltsjahr 2018 103 § 9 Abs. 1 Raumordnungsgesetz (ROG) – Neuauf- stellung des Regionalplans Ruhr durch den Regional- verband Ruhr 101 C: Rechtsvorschriften und Bekanntmachungen anderer Behörden und Dienststellen 71 Frühzeitige Information der Öffentlichkeit • den im Verbandsgebiet liegenden Teil des GEP 99 der gemäß § 9 Abs. 1 Raumordnungsgesetz (ROG) Bezirksregierung Düsseldorf, – Neuaufstellung des Regionalplans Ruhr durch • den Regionalplan „Teilabschnitt Emscher-Lippe“ der den Regionalverband Ruhr Bezirksregierung Münster, • den im Verbandsgebiet liegenden Teil des Regional- Die Regionaldirektorin des Essen, den 28.03.2018 planes „Teilabschnitt Oberbereich Dortmund“ (Dort- Regionalverbandes Ruhr mund/Kreis Unna/Hamm) der Bezirksregierung Arns- als Regionalplanungsbehörde berg, 15/RPR/NA • den im Verbandsgebiet liegenden Teil des Regional- Der Regionalrat beim Regionalverband Ruhr hat be- planes „Teilabschnitt Oberbereiche Bochum und Ha- schlossen, den Regionalplan Ruhr neu aufzustellen. Mit gen“ (Bochum, Herne, Hagen, Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis, dem Regionalplan Ruhr sollen die künftigen Bereiche für Märkischer Kreis) der Bezirksregierung Arnsberg, die Wohnbauflächenentwicklung,