Postdoctoral Funding Schemes in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Chicago Postdoctoral Researcher Policy Manual

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO POSTDOCTORAL RESEARCHER POLICY MANUAL Preamble A Postdoctoral Researcher is an individual who has received a doctoral degree (or equivalent) and is engaged in a temporary and defined period of mentored advanced training to enhance the professional and research independence needed to pursue his or her chosen career path. At the University of Chicago, the postdoctoral experience emphasizes scholarship and continued research training. The Postdoctoral Researcher conducts research under the general oversight of a faculty or other mentor in preparation for a career in academe, industry, government, or the nonprofit sector. In many disciplines postdoctoral work provides essential training for individuals pursuing academic careers and may include opportunities to enhance teaching and other professional skills. Postdoctoral Researchers contribute to the academic community by enhancing the research and education programs of the University. The University strives to provide a stimulating, positive, and constructive experience for the Postdoctoral Researcher by emphasizing the mutual commitment and responsibility of the institution, the faculty and other researchers, and the Postdoctoral Researcher. Policy This policy defines and sets forth terms and conditions relating to the appointment of Postdoctoral Researchers. It applies to both (1) Postdoctoral Scholars (PDS), who are employees of the University and (2) Postdoctoral Fellows (PDF), who are paid stipends by extramural agencies either directly or through the University. Postdoctoral Fellows, however paid, are not employees of the University. Definition Postdoctoral appointments are temporary positions with fixed end dates intended to provide a full-time program of advanced academic preparation and research training. A postdoctoral appointment is not intended for long-term, indefinite, or career appointments, or for short-term appointments where the primary goal is to advance a principal investigator's research. -

The University of Eastern Finland, UEF, Is One of the Largest Multidisciplinary Universities in Finland

The University of Eastern Finland, UEF, is one of the largest multidisciplinary universities in Finland. We offer education in nearly one hundred major subjects, and are home to approximately 15,000 students and 2,800 members of staff. We operate on three campuses in Joensuu, Kuopio and Savonlinna. In international rankings, we are ranked among the leading 300 universities in the world. The Faculty of Health Sciences operates at the Kuopio Campus of the University of Eastern Finland. The Faculty offers education in medicine, dentistry and pharmacy, as well as in some other central fields of the health care sector. The Faculty is research-intensive, and its internationally recognised research activities are closely linked to the strategic research areas of the University. There are approximately 2 500 degree students and about 450 PhD students in the Faculty. The number of staff adds up to almost 700 experts. http://www.uef.fi/en/ttdk/etusivu We are now inviting applications for Postdoctoral Researcher/Assistant Professor/Associate Professor (Tenure Track) (biomedical image and signal analysis) position, A.I. Virtanen Institute for Molecular Sciences, Kuopio Campus (position no 32286) This post is re-opened. Applications of those who have applied for the position earlier will be taken into consideration when the post is filled. In the currently vacant position, the Tenure Track can be entered from the Postdoctoral Researcher or Assistant Professor or Associate Professor level onwards. At the end of the term, the merits of the person will be evaluated to determine whether he or she can proceed to the next level of the Tenure Track without public notice of vacancy.The criteria, objectives and results to be achieved during the term in order to proceed to the next level of the Tenure Track will be agreed in detail with the appointee when signing the contract of employment. -

Clemson University, Ph.D., Learning Sciences, Program Proposal, CAAL, 8/7/2014 – Page 1 CAAL 8/7/14 Agenda Item 4C

CAAL 8/7/14 Agenda Item 4c New Program Proposal Doctor of Philosophy in Learning Sciences Clemson University Summary Clemson University requests approval to offer a program leading to the Doctor of Philosophy in Learning Sciences to be implemented in January 2015. The proposed program is to be offered through traditional instruction. The following chart outlines the stages for approval of the proposal; the Advisory Committee on Academic Programs (ACAP) voted to recommend approval of the proposal. The full program proposal is attached. Stages of Consideration Date Comments Program Planning Summary 2/11/14 received and posted for comment Program Planning Summary 3/30/14 One ACAP member noted that the research considered by ACAP through methods courses appear strong in this degree, electronic review but also suggested adding coursework in cognitive theory and design. Another ACAP member stated that the proposed program is similar to USC Columbia’s Ph.D. program in Educational Psychology and Research. Program Proposal Received 5/15/14 ACAP Consideration 6/19/14 ACAP members suggested the proposal include statements about how the program differs from Educational Psychology programs. ACAP also recommended the addition of recruitment strategy statements to address USC Columbia’s concerns about competition. ACAP requested a revised budget and budget justification. Comments and suggestions 6/20/14 Staff requested additional information about from CHE staff sent to the potential employment opportunities and institution specificity about what students will be able to do and in which positions they might reasonably expect employment. Staff also requested a new letter of evaluation because the letter provided did not adequately address the proposed courses/curriculum, faculty, or resources required. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Yaouen Fily Postdoctoral Researcher Martin Fisher School of Physics, Brandeis University Waltham, MA 02453, USA +1 315-436-6069 yffi[email protected] http://people.brandeis.edu/~yffily Education Ph.D. in Condensed Matter Physics, Université de Tours, France 2009 Master Dynamical systems and statistics of complex matter, Université Paris VI, France 2006 Agrégation de Sciences Physiques, option Physique1 2005 Licence in Physics, Université Paris VI / Ecole Normale Supérieure de Cachan, France 2003 Research Experience Postdoctoral Researcher 2012-present Brandeis University. Advisors: Michael Hagan, Aparna Baskaran. Confined active particles, flagellar beating, chiral self-assembly. Postdoctoral Researcher 2009-2012 Syracuse University. Advisor: Cristina Marchetti. Self-propelled particles, viscous fluid dynamics, linear elasticity, cell motion, jamming transition. Graduate Student 2006-2009 LEMA, CNRS/Université de Tours, France. Advisors: Jean-Claude Soret and Enrick Olive. “Depinning and high velocity dynamics of vortex lattices in type II superconductors – A numerical study”. Trainee February-March 2006 Service de Physique Theorique, C.E.A. Saclay, France. Advisor: Cécile Monthus. Directed polymers in random media. Trainee May-July 2004 Service d’Écologie Sociale, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. Advisor: Jean-Louis Deneubourg. Modeling of cockroach aggregation. Trainee June-July 2003 Kastler-Brossel Lab, Université Paris VI, France. Advisor: Claude Fabre. Design and study of a resonant optical cavity. 1 Agrégation is a highly selective French exam of teaching ability that covers all core undergraduate physics classes and some chemistry. It is taken after a year-long preparation that involves theory as well as giving practice lectures critiqued by experienced educators. 1/4 Curriculum Vitae Yaouen Fily Teaching Experience Postdoctoral Researcher 2009-present At Syracuse University: GRE preparation, 4h, undergraduate level. -

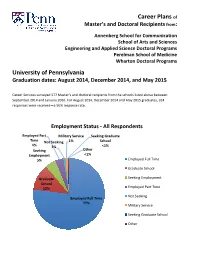

Career Plans of University of Pennsylvania

Career Plans of Master’s and Doctoral Recipients from: Annenberg School for Communication School of Arts and Sciences Engineering and Applied Science Doctoral Programs Perelman School of Medicine Wharton Doctoral Programs University of Pennsylvania Graduation dates: August 2014, December 2014, and May 2015 Career Services surveyed 577 Master’s and doctoral recipients from the schools listed above between September 2014 and January 2016. For August 2014, December 2014 and May 2015 graduates, 324 responses were received—a 56% response rate. Employment Status - All Respondents Employed Part Military Service Seeking Graduate Time Not Seeking 1% School 4% 1% <1% Seeking Other Employment <1% 5% Employed Full Time Graduate School Graduate Seeking Employment School 12% Employed Part Time Not Seeking Employed Full Time 77% Military Service Seeking Graduate School Other Date of Job Offer Acceptance 246 of the 249 Master’s and PhDs who secured full-time employment (including full-time postdoctoral research/fellowship positions) included the date they accepted their job offer when they completed the survey. 80% 72% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 15% 10% 5% 5% 3% 0% Continuing previous Received offer before Received offer within Received offer 3-4 Received offer 5 or employment graduation 1-2 months of months after more months after graduation graduation graduation Top Industries of Full-time Employed Respondents (N=249) 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Education, Higher (College/University) Healthcare, Hospital/Health System Consulting Biomedical Products/Pharmaceuticals/Medical Devices Technology, Computing/Information Systems All Other (industries with less than 10 employed) PhDs 444 individuals received their PhD between August 2014 and May 2015. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Patricia M. Lambert

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Patricia M. Lambert ___________________________________________________________________________________ DATE: August 7, 2018 Department of SSWA Lab: Veterinary Science 206 0730 Old Main Hill Office: Main 245E Utah State University Logan, UT 84322-0730 Office: (435) 797-2603 / Fax: (435) 797-1240 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 1997 Postdoctoral Fellow, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 1994 Ph.D. Anthropology. University of California, Santa Barbara Dissertation Thesis: War and Peace on the Western Front: A Study of Violent Conflict and Its Correlates in Prehistoric Hunter-gatherer Societies of Coastal Southern California. University of California at Santa Barbara. University Microfilms, Ann Arbor. 1986-89 M.A. Anthropology. University of California, Santa Barbara 1980 B.A. Physical Anthropology, Honors. University of California, Santa Barbara MAJOR PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2007- Professor. Anthropology Program, USU 2010-16 Associate Dean of Research and Graduate Studies, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, USU 2012-16 Executive Director, Museum of Anthropology and SDCAV, USU 2012-14 Program Director, Anthropology Program, USU 2011-16 Director, Mountain West Center for Regional Studies, USU 2004-09 Program Director. Anthropology Program, USU. Successful Program Initiatives: M.S. Degree Program in Anthropology Distance Minor in Anthropology with new Distance faculty line (2008) Founding of USU Archaeological Services, Inc. Museum of Anthropology: USU Funded Curator position (2008) -

Session Proposal

19th World UISPP Congress | Meknès, Morocco, 1-6 September 2020 | Session proposal SESSION TITLE: UNTOLD STORIES: WOMEN AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN AFRICA THEME: Historiography, methods and theory AUTHORS: Laura Coltofean-Arizancu, Postdoctoral Researcher | Universitat de Barcelona, Spain | email: [email protected]; [email protected] Ana Cristina Martins, Research Associate | IHC-FCSH NOVA – Pólo Universidade de Évora and Uniarq-UL, Portugal | email: [email protected] Nathan Schlanger, Professor | École nationale des Chartes and UMR Trajectoires, France | email: [email protected] ABSTRACT In the last thirty years, research devoted to women in archaeology has increased considerably, confirming the previously unrecognized role they played in the development of the discipline. However, these studies have mostly focused on renowned and successful female archaeologists from Western Europe, North America and Australia. Little attention has been given to the more conventional and sometimes less visible professional trajectories of women working as museum curators, conservators, educators, illustrators, photographers, or to those who pursued their interest in archaeology as collectors or on the side of their male relatives. As a consequence, women involved in archaeology in Africa, Eastern Europe, Asia and South America have remained largely unknown. This session addresses the various modes by which women have engaged with archaeological practice and knowledge production in Africa, from the nineteenth to the twentieth century. With the -

Tenure-Track Positions at the Rank of Professor Or Associate Professor

Tenure-Track Positions at the Rank of Professor or Associate Professor with Associated Postdoc Positions International Research Organization for Advanced Science and Technology (IROAST) Kumamoto University, Japan I. Position Description: Professor or Associate Professor Level The International Research Organization for Advanced Science and Technology (IROAST), which will be established from April, 2016 in Kumamoto University, Japan, is pleased to invite applications for tenure-track positions at the rank of Professor or Associate Professor for the enhancement and development of international research projects ongoing at the Graduate School of Science and Technology. The positions are available from August 1, 2016, or as soon as possible thereafter. Appointments at this rank are for 5-year terms. After qualification (see section IV), successful applicants will be promoted to tenure posts in the Graduate School of Science and Technology within 5 years. The four priority research areas are as follows: (1) Nano Material Science, (2) Green Energy, (3) Environmental Science and (4) Advanced Green Bio. Nano Material Science covers a wide area including the development of organic functional materials such as graphene oxide nano-sheets, catalysts and metal materials. It also includes the development of innovative materials under extreme conditions. Green Energy includes the development and utilization of renewable resources such as geo-thermal, water, and bio-mass resources. Environmental Science covers a wide area including the protection and evaluation of hydrospheric and atmospheric environments, analysis of climate change, and the protection of underground water and shallow sea areas. Advanced Green Bio covers a wide area for the interdisciplinary life sciences relating to chemical biology, molecular biology, cooperation with medicine, pharmacy, agriculture (such as the development of drug delivery systems), applications of micro-CTs, applications of informatics, and so on. -

Academy of Finland's Funding Terms and Conditions 2019-2020

1 (40) AKA/5/02.04.10/2019 THE ACADEMY OF FINLAND’S FUNDING TERMS AND CONDITIONS 2019–2020 Decision 28 May 2019 These funding terms and conditions of the Academy of Finland (hereafter the Academy) apply to funding calls implemented between 1 September 2019 and 31 August 2020 and to funding decisions based on these calls. 2 (40) Contents PART I APPLYING FOR FUNDING ......................................................................................................................... 5 1. SCOPE OF APPLICATION ..................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Scope of application of these funding terms and conditions .......................................................................... 5 1.2 Receiving and confirming receipt of funding decision, notifying application for advance payment ............. 6 2. APPLYING COST MODELS IN THE ACADEMY OF FINLAND’S RESEARCH FUNDING ........... 7 2.1 Funding percentage.......................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Decisions in accordance with the additional cost model ................................................................. 7 3. BASIC FACILITIES FOR THE PROJECT .............................................................................................. 8 4. COSTS OF FOREIGN SCIENTISTS’ RESEARCH VISITS TO OR RESEARCH IN FINLAND ........ 8 5. CONSIDERING PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT ............................................... -

UC Libraries Academic E-Book Usage Survey

University of California Libraries UC Libraries Academic e-Book Usage Survey Springer e-Book Pilot Project Springer e-Book Pilot Project Reader Assessment Subcommittee Chan Li, California Digital Library Felicia Poe, California Digital Library Michele Potter, UC Riverside Brian Quigley, UC Berkeley Jacqueline Wilson, California Digital Library May 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Table of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Survey Background and Methodology .............................................................................................. 7 Respondent Demographics ....................................................................................................................... 8 II. Academic e-Book Users: Overview ................................................................................................... 9 Preference for Print Books as Compared to e-Books ............................................................................. 11 Influence of Use on Preference for Print Books as Compared to e-Books ............................................. 13 III. Valued e-Book Features ............................................................................................................... -

The Life of P.I. Transitions to Independence in Academia

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/571935; this version posted March 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The life of P.I. Transitions to Independence in Academia Sophie E. Acton1, , Andrew Bell2, , Christopher P. Toseland3, , and Alison Twelvetrees4, 1Stromal Immunology Group, MRC Laboratory for Molecular Cell Biology, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom 2Sheffield Methods Institute, University of Sheffield, Western Bank, Sheffield, S10 2TN, united Kingdom 3School of Biosciences, University of Kent Canterbury, Kent, CT2 7NJ, United Kingdom 4Sheffield Institute for Translational Neuroscience, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S10 2HQ, United Kingdom The data in this report summarises the responses gathered sities or through external sources such as the research coun- from 365 principle investigators of academic laboratories, who cils and larger charities. Lecturers typically follow a proba- started their independent positions in the UK within the last tion scheme which leads to confirmation of their appointment 6 years up to 2018. We find that too many new investigators whilst the situation for research fellows is more precarious. express frustration and poor optimism for the future. These However, externally-funded research fellows typically have data also reveal, that many of these individuals lack the sup- significant funding available for long-term research projects port required to make a successful transition to independence and positions to recruit lab members, allowing more rapid and that simple measures could be put in place by both funders and universities in order to better support these early career re- establishment of research projects compared to lecturers. -

Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing Program

A Publication of The Graduate Center, CUNY Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing Program Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing The Graduate Center 365 Fifth Avenue Room 3317 New York, New York 10016 T: 212.817.7987 F: 212.817.1681 E: [email protected] Doctor of philosophy in nursing program Executive Officer Donna M. Nickitas PhD, NEA- Greetings from Executive Of- Keville Frederickson Schol- BC, CNE, FNAP, RN, FAAN ficer Dr. Donna M Nickitas arship Fund Announcement Deputy Executive Officer Eileen Gigliotti RN, PhD Faculty Achievements Postdoctoral Researcher Mi- Deputy Executive Officer guel A. Villegas-Pantoja Martha Whetsell RN, PhD, ARNP Alumni Achievements In Focus: Retired Faculty Assistant Program Officer Sheren Brunson MA Student Achievements Upcoming Events Editorial Board Donna M. Nickitas PhD, NEA- Jonas Center Nurse Leader BC, CNE, FNAP, RN, FAAN Stephen Jones Scholars Sheren Brunson MA Designer, Editor, & Photographer Stephen Jones 1 CUNY Graduate Center Ph.D. in Nursing N e w s l e t t e r Greetings from the Desk of Executive Officer Dr. Donna M. Nickitas Greetings on behalf of the Faculty and Staff This milestone is reached at the end of of the Nursing Science Program. We are the first year. The first examination tim- pleased to provide the second edition of our ing, content, and format have been program’s E-Newsletter. We are grateful for evaluated and revised since our program began. Students are now required to the excellent work of our Editor, Stephen demonstrate foundational knowledge by Jones, as he highlights the outstanding schol- writing a “State of the Science” paper.