The Himyarite “Knight” and Partho-Sasanian Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johnny Okane (Order #7165245) Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition

johnny okane (order #7165245) Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition Weloe to the Hurlat Pulishig editio of Miro Warfare “eries: Miro Ancients This series of games was original published by Tabletop Games in the 1970s with this title being published in 1976. Each game in the series aims to recreate the feel of tabletop wargaming with large numbers of miniatures but using printed counters and terrain so that games can be played in a small space and are very cost-effective. In these new editions we have kept the rules and most of the illustrations unchanged but have modernised the layout and counter designs to refresh the game. These basic rules can be further enhanced through the use of the expansion sets below, which each add new sets of army counters and rules to the core game: Product Subject Additional Armies Expansion I Chariot Era & Far East Assyrian; Chinese; Egyptian Expansion II Classical Era Indian; Macedonian; Persian; Selucid Expansion III Enemies of Rome Britons; Gallic; Goth Expansion IV Fall of Rome Byzantine; Hun; Late Roman; Sassanid Expansion V The Dark Ages Norman; Saxon; Viking Happy gaming! Kris & Dave Hurlbat July 2012 © Copyright 2012 Hurlbat Publishing Edited by Kris Whitmore Contents Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition ................................................................................................................................... 2 Move Procedures ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

Military Technology in the 12Th Century

Zurich Model United Nations MILITARY TECHNOLOGY IN THE 12TH CENTURY The following list is a compilation of various sources and is meant as a refer- ence guide. It does not need to be read entirely before the conference. The breakdown of centralized states after the fall of the Roman empire led a number of groups in Europe turning to large-scale pillaging as their primary source of income. Most notably the Vikings and Mongols. As these groups were usually small and needed to move fast, building fortifications was the most efficient way to provide refuge and protection. Leading to virtually all large cities having city walls. The fortifications evolved over the course of the middle ages and with it, the battle techniques and technology used to defend or siege heavy forts and castles. Designers of castles focused a lot on defending entrances and protecting gates with drawbridges, portcullises and barbicans as these were the usual week spots. A detailed ref- erence guide of various technologies and strategies is compiled on the following pages. Dur- ing the third crusade and before the invention of gunpowder the advantages and the balance of power and logistics usually favoured the defender. Another major advancement and change since the Roman empire was the invention of the stirrup around 600 A.D. (although wide use is only mentioned around 900 A.D.). The stirrup enabled armoured knights to ride war horses, creating a nearly unstoppable heavy cavalry for peasant draftees and lightly armoured foot soldiers. With the increased usage of heavy cav- alry, pike infantry became essential to the medieval army. -

Mithridatic Pontic 100Bc – 46 Bc

MITHRIDATIC PONTIC 100BC – 46 BC The following Army Organisation List (AOL) will enable you to build a Mithridatic Pontic army for War & Conquest. Please refer to the introductory online Army Organisation List guide document. This is Version 3, April 2020. Feedback and observations are most welcome. Thanks to John O'Connor for creating the original list. The Kingdom of Pontus, located in the north of Asia Minor on the southern shores of the Black Sea, was one of Rome’s most persistent enemies. Pontus ruled over a large and wealthy area including most of the Black Sea coast, the Crimean Bosporus, Cappadocia and parts of Armenia. Due to this her armies contained an eclectic mix of troops from all of the nations in the area and large numbers of mercenaries. Her armies defeated Roman armies several times during the Mithridatic Wars but, unfortunately, only defeats at 2nd Chaeronea, Orchomenus and Zela (Veni, Vidi, Vici) are written about in most general histories – that’s if the Mithridatic Wars get a mention at all. Pontus was also responsible for the only recorded successful use of scythed chariots at the River Amnias against the Bithynians. ARMY COMPOSITION PERSONALITIES OF WAR SUPPORTING FORMATIONS Up to 25% of the points value of the army Up to 50% of the points value of the army may be Personalities of War may be selected from supporting An Army General must be selected. formations Strategy Intervention Points are automatically pooled in a Pontic army ALLIED FORMATIONS except from allied commanders Up to 25% of the points value of the army may be selected from allied formations CAVALRY Up to 50% of the points value of the army LEGENDS OF WAR may be cavalry. -

The Armies of Belisarius and Narses

1 O’ROURKE: ARMIES OF BELISARIUS AND NARSES ARROW-STORMS AND CAVALRY PIKES WARFARE IN THE AGE OF JUSTINIAN I, AD 527-565 THE ARMIES OF BELISARIUS AND NARSES by Michael O’Rourke mjor (at) velocitynet (dot) com (dot) au Canberra Australia September 2009 1. Introduction: “Rhomanya” 2. Troop Numbers 3. Troop Types 4. Tactics 5. Selected Battles 6. Appendix: Arrows, Armour and Flesh “Rhomanya”: The Christian Roman Empire of the Greeks Having been conquered by the Romans, the Aramaic- and Greek-speaking Eastern Mediterranean lived for centuries under imperial rule. Its people had received full citizenship already in 212 AD. So the East Romans naturally called themselves Rhomaioi, the Greek for ‘Romans’. The term Rhomanya [Greek hê Rhômanía:‘Ρ ω µ α ν ’ι α ] was in use already in the 300s (Brown 1971: 41). Middle period examples denoting the ‘Eastern’ Empire are found in the 600s - as in the Doctrina Jacobi - and in the 800s in various entries in the chronicle of Theophanes (fl. 810: e.g. his entry for AD 678). Although we do not find the name Rhômanía in Procopius, fl. AD 550, or in Anna Comnena, fl. 1133, it does occur in the writings of emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, fl. 955. The later medieval West, after AD 800, preferred the style ‘Greek Empire’. After 1204 the Latins used the term Romania to refer generally to the Empire and more specifically to the lower Balkans (thus English ‘Rumney wine’, Italian vino di Romania). Our own name Rumania/Romania, for the state on the northern side of the Danube, was chosen in 1859. -

THE STRATEGIC DEFENSE of the ROMAN ORIENT a Thesis

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE NISIBIS WAR (337-363 CE) THE STRATEGIC DEFENSE OF THE ROMAN ORIENT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in History By John Scott Harrel, MG (Ret.) December 2012 © 2012 John Scott Harrel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii The thesis of John Scott Harrel is approved: ____________________________ _____________ Dr. Donal O’Sullivan Date ____________________________ _____________ Dr. Joyce L. Broussard Date ____________________________ _____________ Dr. Frank L. Vatai, Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii Dedication To the men and women of the California Army National Guard and the 40th Infantry Division, who in the twenty-first century, have marched, fought and died in the footsteps of the legions I & II Parthia, Joviani and Herculiani. iv Table of Contents Copy Right ii Signature Page iii Dedication iv List of Maps vi List of Illustrations vii Abstract viii Chapter 1: The Nisibis War (337-363): Thesis, Sources, and Methodology. 1 Chapter 2: Background of The Nisibis War. 15 Chapter 3: The Military Aspects of the Geography Climate and 24 Weather of the Roman Orient. Chapter 4: The Mid-4th Century Roman Army and the Strategic 34 Defense of the East. Chapter 5: The Persian Army and the Strategic Offense. 60 Chapter 6: Active Defense, 337-350. 69 Chapter 7: Stalemate, 251-358 78 Chapter 8: Passive Defense, 358-361 86 Chapter 9: Strategic Offense, 362-363 100 Chapter 10: Conclusion 126 Bibliography 130 v List of Maps 1. King Shapur’s Saracen Wars 324-335 18 2. Nisibis War Theater of Operations 25 3. -

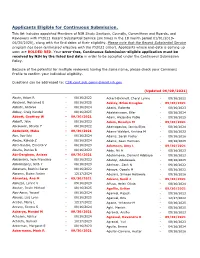

Applicants Eligible for Continuous Submission

Applicants Eligible for Continuous Submission. This list includes appointed Members of NIH Study Sections, Councils, Committees and Boards, and Reviewers with FY2021 Recent Substantial Service (six times in the 18 month period 01/01/2019- 06/30/2020), along with the End dates of their eligibility. Please note that the Recent Substantial Service program has been terminated effective with the FY2021 cohort. Applicants whose end-date is coming up soon are BOLDED RED. Your error-free, Continuous Submission-eligible application must be received by NIH by the listed End date in order to be accepted under the Continuous Submission Policy. Because of the potential for multiple reviewers having the same name, please check your Commons Profile to confirm your individual eligibility. Questions can be addressed to: [email protected] (Updated 06/09/2021) Abate, Adam R - 08/16/2022 Ackert-Bicknell, Cheryl Lynne - 08/16/2022 Abazeed, Mohamed E - 08/16/2025 Ackley, Brian Douglas - 09/30/2021 Abbate, Antonio - 08/16/2024 Adachi, Roberto - 08/16/2023 Abbey, Craig Kendall - 08/16/2025 Adalsteinsson, Elfar - 08/16/2024 Abbott, Geoffrey W - 09/30/2021 Adam, Alejandro Pablo - 08/16/2025 Abbott, Jake - 08/16/2023 Adam, Rosalyn M - 09/30/2021 Abcouwer, Steven F - 08/16/2022 Adamopoulos, Iannis Elias - 08/16/2024 Abdellatif, Maha - 09/30/2021 Adams Waldorf, Kristina M - 08/16/2022 Abe, Jun-Ichi - 08/16/2024 Adams, Sarah Foster - 08/16/2026 Abebe, Kaleab Z - 08/16/2024 Adams, Sean Harrison - 08/16/2025 Abel-Santos, Ernesto V - 08/16/2023 Adamson, Amy -

ARMY COMPOSITION SASSANID PERSIA 220 AD to 637 AD

SASSANID PERSIA 220 AD to 637 AD The Sassanids were one of the politically powerful noble families of Iran and successfully revolted against Parthian rule, founding a dynasty that would provide the later Roman Empire with its toughest opponent, and continue to be a problem for the Byzantine Empire until overcome unexpectedly by the Arab expansion. The early Sassanid armies resembled their Parthian predecessors, with a core of Tanurigh, “oven-men” or cataphracts, supported by clouds of horse archers. Later the Azatan warrior class wore lighter equipment and the importance of the horse archer waned, especially when the Azatan recommenced using the bow in the later period. Both Early and Late variants of the army may be constructed from this list. Units marked (E) may only be used in early armies. ARMY COMPOSITION Horse Archers have a bow. Evade, May be fielded as Skirmishers with Parthian Shot. In either formation, Commanders: Up to 6 may have shield (+1). Cavalry: At least 50% Iranians have javelins and shield. Evade. May be Infantry: Up to 50% fielded as skirmishers for 18 points per base. Allies and Vassals: Up to 33% In an early army, there must be at least one light Elephants: Up to 1 per 400 points cavalry figure for each heavy cavalry figure in the All troops other than Allies and Vassals are Used to army. elephants. In a late army there must be at least one light cavalry figure for each heavy cavalry figure in the army, COMMANDERS unless all Azatan Noble cavalry have bows. A C Pts INFANTRY 0-1 Shah +2 10 50 D C Pts or 0-1 General +2 9 0 Militia Spearmen 5 6 14 Noble +2 +2 20 Levy Spearmen 5 5 8 All ride horses. -

Swordpoint Quick Reference Sheet V1.5

Quick Reference Sheet v1.5 By Andy Cummings 1. Inial Phase Take Cohesion test when: 1. Test for loss of Cohesion due to fleeing friends within 4” 1. Fleeing friends within 4" at the start of the turn 2. Terror test for mounted units within 8” of elephant 2. Friends break or are destroyed in hand‐to‐hand combat within 12" 3. Test units outside 12” for death of general previous turn 3. Charged in the flank or rear Modifiers 4. Impetuous/Warband tests (Charge or Take Cohesion Test) 4. The Army General is slain 5. Cohesion test for troops to return from off table 5. The unit suffers 25% casuales Discouraged +1 6. Remove Discouraged markers from units not in combat or fleeing from shoong in one turn Depleted (<= half bases) +2 2. Shoong Phase # Shoong Dice 1. Shoong is simultaneous Unit Type Weapon # Bases #dice per base 2. Declare all targets to be shot at Formed Infantry Bow, Long Bow First two rows 1 per Base 3. Resolve shoong Plus all except Levy, inferior or units front row not shoong +1 per 2 in 2nd row 4. Test for Commanders killed (12 on 2d6) Formed Mounted* Bow, Long Bow First two rows 1 5. Take any cohesion tests Foot Skirmishers Any First two rows 1 6. Award momentum tokens Mtd Skirmishers Any All bases 1 Target Priority All other Units Hand hurled weapons, First row only 1 1. Closest enemy able to charge Slings, Handguns, Xbow 2. Closest enemy Elephant, Chariots All All 1 3. If two or more enemy units are equidistant from the *Mounted: Cavalry, Camels and Chariots shooters and covering an equal amount of their front‐ Shoong ranges To hit target modifiers age, then shoong is split equally Weapon Short Long Factor To Hit 4. -

The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire

The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire EDWARD N. LUTTWAK THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Luttwak, Edward. The grand strategy of the Byzantine Empire / Edward N. Luttwak. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03519-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Byzantine Empire—Military policy. 2. Strategy—History—To 1500. 3. Military art and science—Byzantine Empire— History. 4. Imperialism—History—To 1500. 5. Byzantine Empire—History, Military. 6. Byzantine Empire—Foreign relations. I. Title. U163.L86 2009 355′.033549500902—dc22 2009011799 Contents List of Maps vii Preface ix I The Invention of Byzantine Strategy 1 1 Attila and the Crisis of Empire 17 2 The Emergence of the New Strategy 49 II Byzantine Diplomacy: The Myth and the Methods 95 3 Envoys 97 4 Religion and Statecraft 113 5 The Uses of Imperial Prestige 124 6 Dynastic Marriages 137 7 The Geography of Power 145 8 Bulghars and Bulgarians 171 9 The Muslim Arabs and Turks 197 vi • Contents III The Byzantine Art of War 235 10 The Classical Inheritance 239 11 The Strategikon of Maurikios 266 12 After the Strategikon 304 13 Leo VI and Naval Warfare 322 14 The Tenth-Century Military Renaissance 338 15 Strategic Maneuver: Herakleios Defeats Persia 393 Conclusion: Grand Strategy and the Byzantine “Operational Code” 409 Appendix: Was Strategy Feasible in Byzantine Times? 421 Emperors from Constantine I to Constantine XI 423 Glossary 427 Notes 433 Works Cited 473 Index of Names 491 General Index 495 Maps 1. -

De Bellis Multitudinis

DE BELLIS MULTITUDINIS Wargames Rules for Ancient and Medieval Battle 3000 BC to 1500 AD by Phil Barker and Richard Bodley Scott Version 3.2 April 2011 Explanatory note for Version 3.2 Phil Barker and Richard Bodley Scott jointly developed all versions of DBM up to 3.0, published in July 2000. After that they went their separate ways. Phil started to develop DBMM which he intended to be the successor to DBM. Richard at that time did not consider that changes to DBM were needed. The prototype of DBMM was put on the web for open discussion and after over two years testing, DBMM 1.0 was published in 2007. Meanwhile Richard had decided to accept suggestions and update DBM and in 2005 he issued amendment sheets to update DBM to version 3.1; Phil had no direct input to this version, but many of the changes resemble sections of the DBMM rules. The changes between 3.0 and 3.1 are indicated in blue. In 2009 John Graham-Leigh (not a member of Wargames Research Group but an organiser of many DBM competitions) developed some amendments as house rules for use in his competitions. In 2011 Richard approved these amendments as DBM Version 3.2. (Phil, being fully occupied with version 2.00 of DBMM which was published in 2010, took no part in these discussions.) The 3.2 amendments are shown in red in this document. Phil and Richard have been prevailed upon by John to permit the electronic publication of DBM version 3.2, partly as an historical document and partly for the convenience of those who wish to continue using these rules. -

2. Shooting Phase 3. Movement Phase

Quick Reference Sheet v1.4 By Andy Cummings 1. Initial Phase Take Cohesion test when: 1. Test for loss of Cohesion due to fleeing friends within 4” 1. Fleeing friends within 4" at the start of the turn 2. Terror test for mounted units within 8” of elephant 2. Friends break or are destroyed in hand-to-hand combat within 12" 3. Test units outside 12” for death of general previous turn 3. Charged in the flank or rear Modifiers 4. Impetuous/Warband tests (Charge or Take Cohesion Test) 4. The Army General is slain 5. Cohesion test for troops to return from off table 5. The unit suffers 25% casualties Discouraged +1 6. Remove Discouraged markers from units not in combat or fleeing from shooting in one turn Depleted (<= half bases) +2 2. Shooting Phase # Shooting Dice 1. Shooting is simultaneous Unit Type Weapon # Bases #dice per base 2. Declare all targets to be shot at Formed Infantry Bow, Long Bow First two rows 1 per Base 3. Resolve shooting +1 per 2 in 2nd row 4. Test for Commanders killed (12 on 2d6) Formed Mounted* Bow, Long Bow First row only 1 5. Take any cohesion tests Foot Skirmishers Any First two rows 1 6. Award momentum tokens Mounted Skirmishers Any All bases 1 Target Priority All other Units Hand hurled weapons, First row only 1 1. Closest enemy able to charge Slings, Handguns, Xbow 2. Closest enemy Elephant, Chariots All All 1 3. If two or more enemy units are equidistant from the *Mounted: Cavalry, Camels and Chariots shooters and covering an equal amount of their front- Shooting ranges To hit target modifiers age, then shooting is split equally Weapon Short Long Factor To Hit 4. -

Who Were the Cataphracts?

Who were the cataphracts? An archaeological and historical investigation into ancient heavy cavalry in the Near East By Ruben Modderman Figure 1: Historical reenactment of a Sassanian cataphract Figure 1: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ancient_Sasanid_Cataphract_Uther_Oxford_2003_06 _2(1).jpg Adres: Hildebrandpad 204, 2333 DB, Leiden E-mailadres: [email protected] Telefoonnummer: 06-13508753 Who were the cataphracts? An archaeological and historical investigation into ancient heavy cavalry in the Near East Name Author: Ruben Modderman Studentnumber: s1116444 Course: Bachelor thesis Name supervisor: Dr. M.J. Versluys Specialisation: Classical and Mediterranean Archaeology University of Leiden, Faculty of Archaeology Leiden, 29-12-2014, Final version Content 1. Introduction §1.1 Identifying the cataphract 5 §1.2 What is cataphract cavalry? 6 §1.3 Chronology and geography 6 §1.4 The horse before antiquity 7 §1.4.1 Use of the horse in prehistoric times 7 §1.4.2 The origin of cavalry 10 2. Ancient sources on cataphracts and related cavalry 13 §2.1 Terminology 13 §2.2 Greek Sources 14 §2.2.1 Xenophon 14 §2.2.2 Polybius 16 §2.2.3 Plutarch 17 §2.2.4 Cassius Dio 20 §2.3 Latin Sources 20 §2.3.1 Livy 21 §2.3.2 Quintus Curtius Rufus 22 §2.3.3 Ammianus Marcellinus 23 §2.4 Other sources 23 §2.5 Reliability 25 3. Archaeological evidence 26 §3.1 Frieze of horsemen, Ḫalčayan, Uzbekistan 26 §3.2 Tang-E Sarvak relief, Iran 27 §3.3 Relief, Tang-E Ab, Firuzabad, Iran 31 §3.4 City, Dura-Europos, Syria 34 3.4.1 Preservation of material 35 3.4.2 Horse trappers 37 3.4.3 Rider armour and weaponry 40 3.4.4 Graffito’s 42 §3.5 Relief of a horseman, Taq-E Bostan, Iran.