History of the Finn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Team Portraits Emirates Team New Zealand - Defender

TEAM PORTRAITS EMIRATES TEAM NEW ZEALAND - DEFENDER PETER BURLING - SKIPPER AND BLAIR TUKE - FLIGHT CONTROL NATIONALITY New Zealand HELMSMAN HOME TOWN Kerikeri NATIONALITY New Zealand AGE 31 HOME TOWN Tauranga HEIGHT 181cm AGE 29 WEIGHT 78kg HEIGHT 187cm WEIGHT 82kg CAREER HIGHLIGHTS − 2012 Olympics, London- Silver medal 49er CAREER HIGHLIGHTS − 2016 Olympics, Rio- Gold medal 49er − 2012 Olympics, London- Silver medal 49er − 6x 49er World Champions − 2016 Olympics, Rio- Gold medal 49er − America’s Cup winner 2017 with ETNZ − 6x 49er World Champions − 2nd- 2017/18 Volvo Ocean Race − America’s Cup winner 2017 with ETNZ − 2nd- 2014 A class World Champs − 3rd- 2018 A class World Champs PATHWAY TO AMERICA’S CUP Red Bull Youth America’s Cup winner with NZL Sailing Team and 49er Sailing pre 2013. PATHWAY TO AMERICA’S CUP Red Bull Youth America’s Cup winner with NZL AMERICA’S CUP CAREER Sailing Team and 49er Sailing pre 2013. Joined team in 2013. AMERICA’S CUP CAREER DEFINING MOMENT IN CAREER Joined ETNZ at the end of 2013 after the America’s Cup in San Francisco. Flight controller and Cyclor Olympic success. at the 35th America’s Cup in Bermuda. PEOPLE WHO HAVE INFLUENCED YOU DEFINING MOMENT IN CAREER Too hard to name one, and Kiwi excelling on the Silver medal at the 2012 Summer Olympics in world stage. London. PERSONAL INTERESTS PEOPLE WHO HAVE INFLUENCED YOU Diving, surfing , mountain biking, conservation, etc. Family, friends and anyone who pushes them- selves/the boundaries in their given field. INSTAGRAM PROFILE NAME @peteburling Especially Kiwis who represent NZ and excel on the world stage. -

OL-Sejlere Gennem Tiden

Danske OL-sejlere gennem tiden Sejlsport var for første gang på OL-programmet i 1900 (Paris), mens dansk sejlsport debuterede ved OL i 1912 (Stockholm) - og har været med hver gang siden, dog to undtagelser (1920, 1932). 2016 - RIO DE JANIERO, BRASILIEN Sejladser i Finnjolle, 49er, 49erFX, Nacra 17, 470, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Bronze i Laser Radial: Anne-Marie Rindom Bronze i 49erFX: Jena Mai Hansen og Katja Salskov-Iversen 4. plads i 49er: Jonas Warrer og Christian Peter Lübeck 12. plads i Nacra 17: Allan Nørregaard og Anette Viborg 16. plads i Finn: Jonas Høgh-Christensen 25. plads i Laser: Michael Hansen 12. plads i RS:X(m): Sebastian Fleischer 15. plads i RS:X(k): Lærke Buhl-Hansen 2012 - LONDON, WEYMOUTH Sejladser i Star, Elliot 6m (matchrace), Finnjolle, 49er, 470, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Sølv i Finnjolle: Jonas Høgh-Christensen. Bronze i 49er: Allan Nørregaard og Peter Lang. 10. plads i matchrace: Lotte Meldgaard, Susanne Boidin og Tina Schmidt Gramkov. 11. plads i Star: Michael Hestbæk og Claus Olesen. 13. plads i Laser Radial: Anne-Marie Rindom. 16. plads i 470: Henriette Koch og Lene Sommer. 19. plads i Laser: Thorbjørn Schierup. 29. plads i RS:X: Sebastian Fleischer. 2008 - BEIJING, QINGDAO Sejladser i Yngling, Star, Tornado, 49er, 470, Finnjolle, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Guld i 49er: Jonas Warrer og Martin Kirketerp. 6. plads i Finnjolle: Jonas Høgh-Christensen. 19. plads i RS:X: Bettina Honoré. 23. plads i Laser: Anders Nyholm. 24. plads i RS:X: Jonas Kældsø. -

Finn World Masters 2019

Finn World Masters 2019 Finn World Masters 2019 in Skovshoved, Denmark Bid proposal by Royal Danish Yacht Club (KDY) Presentation agenda: o Home waters of Finn Class Legends o Grass fields for tents o Royal Danish Yacht Club o Boat Yard hall o Large international regattas o Skovshoved o Venue: Skovshoved o Wonderful Copenhagen o Skovshoved Harbor o Lonely Planet on Copenhagen o Aerial view o “Hygge” in Copenhagen o One of the ramps and dinghy park o And for the ladies… o Map o Please vote for us o Sailing Area o Contact o Accommodation o Social events Home waters of Finn Class legends… The Royal Danish Yacht Club (KDY) will offer Finn Master sailors from all over the world to sail in the home waters of Paul Elvström, Henning Wind, Lasse Hjortnäs, Stig Westergaard and Jonas Høgh-Christensen. When it comes to Finn sailing, Denmark has a great history and tradition. 4 Olympic medals won, 10 Finn Gold Cup victories, a strong national team squad and a very active fleet of master sailors. Royal Danish Yacht Club • The Royal Danish Yacht Club is the oldest and largest sailing club in Denmark (150th anniversary in 2016) • The club is a very active club and experienced when it comes to organizing international regattas • The club has three stations north of Copenhagen: Tuborg Harbor, Skovshoved Harbor and Rungsted Harbor Large international regattas - hosted by Royal Danish Yacht Club the last 10 years: 2007 Farr40 Worlds 2015 M32 Scandinavian Series 2007 Danish Open, WMRT 2016 Danish Open, WMRT 2008 Danish Open, WMRT 2016 Match Race Europeans 2009 470 Worlds 2016 ORC-Worlds 2009 Danish Open WMRT 2016 5.5m Worlds 2011 Snipe Worlds 2016 8mR Europeans 2011 J/80 Worlds 2016 Classic Meter Yacht Cup 2013 X-Yachts Gold Cup 2017 Euro Cup 29er 2015 X-Yacht Gold Cup, X35 Worlds … and many more 2015 Sailing Champions League Venue: Skovshoved Skovshoved Harbor The proposed venue is Skovshoved Harbor, which has just been expanded and modernized with perfect facilities to host large events. -

WBYC Membership Packet

Willow Bank Yacht Club has been a fixture on the Cazenovia Lake shoreline since 1949. Originally formed as a sailing club, over the years it has become a summer home to many Cazenovia and surrounding area families. Willow Bank provides its members with outstanding lake frontage and views, docks, private boat launch, picnic area, beach, swimming area, swimming lessons, sailing lessons, children’s programming, Galley take-out restaurant and a lively social program. The adult sailing program at Willow Bank is one of the most active in Central New York. Active racing fleets include: Finn, Flying Dutchman, Laser, Lightning and Sunfish. Each of these fleets host a regatta over the summer and fleet members will often travel to other area clubs for regattas as well. Formal club point races are held on Sundays. These are races to determine a club champion in each fleet. This format provides for a fun competition within the fleets. On Saturdays, the club offers Free-for-All races which allow members to go out and get some experience racing in any class of sailboat. Adults also have sailing opportunities during the week with our Women of Willow Bank fleet sailing and socializing on Wednesday evenings and, on Thursday evenings, we now have an informal sailing and social program for all members. In addition, we offer group adult lessons and private lessons for anyone looking to learn how to sail. For our youngest members we have a great sand beach and a lifeguarded swimming area which allows hours of summer fun! Swimming lessons, sailing lessons, and Junior Fleet racing, round out our youth programs. -

January 2009

February 2009 Official Publication of Alamitos Bay Yacht Club isaf youth world Volume 82 • Number 2 qualifier Rich Roberts photos underthesunphotos.com Jim Drury photo boat captain Boys International 420s ride a fair southwesterly downwind with downtown Long Beach in the background air wind carries Youth winners on to Brazil Finally, a gentle sea breeze arrived on the third and last day of the 2009 US Sailing ISAF Youth World Qualifier and F US Youth Multihull Championship in time to sweep a group of America’s best young sailors along to the 39th Volvo Youth Sailing ISAF World Championship at Buzios, Brazil July 9-18. “It hasn’t sunk in yet,” said Marissa Lihan, 17, of Ft. Lauderdale, Fla. “I guess I’ll have to start learning Portuguese.” She who won the girls Laser Radial class on a tiebreaker with Emily Billing, 17, of Clearwater, Fla., but only after a wrenching protest hearing about an improper life jacket. Other winners were Chris Barnard, 17, of Newport Beach, in boys Laser Radials; Morgan Kiss, 15, Holland, Mich., and crew Laura McKenna, 17, Palo Alto, Calif., in Club 420s; and Korbin Kirk, 14, Long Beach, and crew Daniel Segerblom, 13, Costa Mesa, Calif., in Hobie 16s. The latter youngsters, neither of whom had ever sailed a catamaran until two weeks ago, also collected the national Youth Multihull title for the Arthur J. Stevens Trophy. Marissa Lihan won Laser Radials, but you More than three hours after racing won’t see this life jacket again concluded, Ian Liberty, 16, Colts Neck, N.J., and crew Alexander Whipple, 17, Plandome, N.Y., won the Boys International 420 title after frontrunners Judge Ryan, San Diego, and crew Chris Segerblom, Costa Mesa, lost a request for redress. -

Maritime Service Report

Major Sailing Events in Pwllheli 2012 We are delighted to include details of Clwb Hwylio Pwllheli’s programme of major competitive sailing events for the 2012 season. In the London Olympic year Pwllheli is delighted to be hosting the International Finn World Masters championship and International Laser UK ranking event. The UK will have medal prospects in both classes at the Olympics in August 2012 in Weymouth. Pwllheli Sailing Club is hosting the UK championships for the International Optimist and International Topper junior ‘Olympic Feeder’ classes. These will be the two largest dinghy competitions in the UK this year. There is no doubt Pwllheli is one of the premier event venues in the UK and with commencement of the building of the new National Sailing Academy the future remains bright for sailing in Wales. 1 - 6 April RYA UK Youth championships This is the premier event in the UK youth sailing programme and is used to select sailors to represent the UK at the ISAF Youth Worlds. Over 220 of the finest youth competitors (under19) are expected to compete in 6 classes of dinghy and windsurfer. 21 - 22 April Welsh Youth and Junior championships Over 120 of the best youth and junior sailors in Wales compete for national honours. 27 May - 1 June International Finn World Masters championships This championship is sailed in the Olympic dinghy in which Ben Ainslie has won gold at the last two Olympics. Competitors are over 40 years old and prizes are awarded by age categories, including the Legends who are over 70. In excess of 150 competitors, including current and former Olympians, are expected from Europe and the rest of the World. -

De/Colonizing Preservice Teacher Education: Theatre of the Academic Absurd

Volume 10 Number 1 Spring 2014 Editor Stephanie Anne Shelton http://jolle.coe.uga.edu De/colonizing Preservice Teacher Education: Theatre of the Academic Absurd Dénommé-Welch, Spy, [email protected] University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada Montero, M. Kristiina, [email protected] Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Abstract Where does the work of de/colonizing preservice teacher education begin? Aboriginal children‘s literature? Storytelling and theatrical performance? Or, with a paradigm shift? This article takes up some of these questions and challenges, old and new, and begins to problematize these deeper layers. In this article, the authors explore the conversations and counterpoints that came about looking at the theme of social justice through the lens of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (FNMI) children‘s literature. As the scope of this lens widened, it became more evident to the authors that there are several filters that can be applied to the work of de/colonizing preservice teacher education programs and the larger educational system. This article also explores what it means to act and perform notions of de/colonization, and is constructed like a script, thus bridging the voices of academia, theatre, and Indigenous knowledge. In the first half (the academic script) the authors work through the messy and tangled web of de/colonization, while the second half (the actors‘ script) examines these frameworks and narratives through the actor‘s voice. The article calls into question the notions of performing inquiry and deconstructing narrative. Key words: decolonizing education; Indigenizing the academy; preservice teacher education; performing decolonization; decolonizing narrative; Indigenous knowledge; First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples of Canada; North America. -

Performance Award Archives

Performance Award Archives The Performance Award category was introduced in 1994 and since this time many great achievements in the sport of yachting have been recognised. The category was previously known as the Merit Award, in 2010 the category was renamed the Performance Award. Year Awardees Details Peter Burling & Blair Tuke 1st 49er World Championships 2019 & 2020 Logan Dunning Beck & Oscar 5th 49er World Championships 2019 Gunn Honda Marine - David 1st JJ Giltinan Trophy for 3rd consecutive year McDiarmid, Matt Steven & Brad Collins Josh Junior 1st Finn Gold Cup 2020 (World Championships) Knots Racing - Nick Egnot- 2nd World Sailing Match Race Rankings 2020 Johnson, Sam Barnett, Bradley McLaughlin & Zak 2020 Merton Scott Leith 1st Laser World Masters 2020 Alex Maloney & Molly Meech 1st 49erFX Oceania Championship 2019 2nd 49erFX Oceania Championship 2020 2nd World Cup Series Enoshima 2019 Andy Maloney 6th Finn Gold Cup 2020 (World Championships) Sam Meech 8th Laser World Championships 2020 Lukas Walton-Keim & Justina 3rd Mixed Formula Kite European Championships 2019 Kitchen Micah Wilkinson & Erica 7th Nacra17 World Championships 2020 Dawson Peter Burling & Blair Tuke 1st 49er European Championships 2019 1st 49er Olympic Test Event 2019 Logan Dunning Beck & Oscar 1st 49er Kiel Week 2019 Gunn George Gautrey 3rd place Laser Worlds 2019 Knots Racing: Nick Egnot- 1st Grade 1 Match Race Germany 2019 Johnson, Sam Barnett, 1st New Zealand Match Racing Nationals 2019 Bradley McLaughlin, Zak 3rd World Sailing Match Race Rankings 2019 Merton -

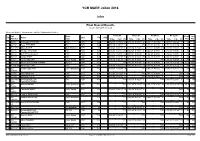

2010 Finn Gold Cup Scoring.Xlsx

. St. Francis Yacht Club August 27‐September 4, 2010 RESULTS Medal/ T Place Bow Sail # Owner/Skipper Race 1Race 2Race 3Race 4Race 5Race 6 Race 7Race 8Race 9Race 10 Total Final O 1 4GBR 11 Edward Wright 183111325312[18]22 2 2ESP 100 Rafael Trujillo 2 1 35 10 81132520[35]53 3 5GBR 41 Giles Scott 1026547361418[10]56 4 3USA 4 Zach Railey 5574510577184[18]59 5 10 FRA 115 Thomas le Breton8733312104888/DNF14[88]72 6 12 SLO 5 Gasper Vincec 11626113026811310[30]94 7 16 GBR 85 Andrew Mills 14 22 5 15 10 15 4 10 32 6 6 [32] 107 8 1CRO 524 Ivan Kljakovic Gaspic31537961613189108[37]107 9 15 GBR 88 Mark Andrew 1211102 39226 12121112[39]110 10 40 AUS 1 Brendan Casey 412418191481351316[41]112 11 6CRO 25 Marin Misura 26 4 8 14 22 8 7 9 15 16 3 [26] 106 12 18 SWE 11 Daniel Birgmark 11 20 17 17 7 11 17 1 23 7 1 [23] 109 13 8FRA 112 Jonathan Lobert 19 31 14 7 2 18 11 15 10 14 4 [31] 114 14 41 DEN 2 Jonas Høgh‐Christensen6638123823142486[38]119 15 20 NZL 1 Dan Slater 32172811264 9 11131215[32]146 16 47 ITA 146 Michele Paoletti 179 12199 171514302414[30]150 17 23 SWE 6 Björn Allansson 288 1825365 122016212[36]155 18 39 SLO 573 Vasilij Zbogar 9 359 16156 3217222512[35]163 19 52 AUS 221 Anthony Nossiter 2710231317271616142018[27]174 20 17 NED 842 Pieter‐Jan Postma 29 18 40 34 28 13 28 24 6 2 7 [40] 189 21 11 ITA 117 Giorgio Poggi 25 25 11 21 13 2 27 30 29 32 13 [32] 196 22 21 CZE 1 Michael Maier 20 19 27 23 23 20 20 19 17 17 35 [35] 205 23 14 POL 17 Piotr Kula 35284 2225262527274710[47]229 24 24 ESP 7 Alejandro Muscat 7 14192420322339333522[39]229 25 25 GER -

Manage2sail Report

YCB MARE Jollen 2018 Jollen Final Overall Results As of 7 SEP 2018 At 14:20 Discard rule: Global: 4. Scoring system: Low Point. Rating system: Yardstick. Sail Boat R1 09.05. R4 27.06. R5 04.07. R7 22.08. Total Net Rk. Name Club YS CDL Number Type Time Calc. Pl. Time Calc. Pl. Time Calc. Pl. Time Calc. Pl. Pts. Pts. 1 SUI 5 Christoph CHRISTEN Finn YCB 109 0:52:14 0:47:55 (2) 0:41:19 0:37:54 2 0:41:17 0:37:52 1 0:30:54 0:28:20 1 6 4 2 SUI 67 Peter THEURER Finn YCB 109 0:52:49 0:48:27 3 (DNC) 0:42:01 0:38:32 3 0:31:22 0:28:46 2 37 8 3 SUI 3782 Mahé RATTE Moth Hydrofoil YCB 72 0:30:43 0:42:39 1 0:26:24 0:36:40 1 0:33:01 0:45:51 (13) 0:21:52 0:30:22 7 22 9 4 SUI 55 Philippe MAURON Finn YCB 109 0:56:32 0:51:51 (10) 0:42:48 0:39:15 4 0:42:49 0:39:16 6 0:32:48 0:30:05 6 26 16 5 SUI 51 Ueli APPENZELLER Finn YCB 109 0:55:15 0:50:41 (7) 0:43:37 0:40:00 7 0:44:28 0:40:47 7 0:32:22 0:29:41 4 25 18 6 SUI 89 Lorenz KURT Finn YCB 109 0:54:16 0:49:47 5 0:43:38 0:40:01 (8) 0:42:18 0:38:48 5 0:33:16 0:30:31 8 26 18 7 SUI 9 Lorenz MÜLLER Laser Radial YCB 116 1:00:42 0:52:19 11 0:45:59 0:39:38 6 (DNC) 0:35:33 0:30:38 9 55 26 8 SUI 142 Sibylle Andrea FREI MÄDER Europe YCB 118 (DNC) 0:48:29 0:41:05 11 0:48:09 0:40:48 8 0:37:23 0:31:40 13,5 61,5 32,5 9 SUI66/ 84 Panos MALTSIS Finn YCB 109 1:00:55 0:55:53 (13) 0:45:45 0:41:58 13 0:44:47 0:41:05 9 0:34:15 0:31:25 11 46 33 10 SUI Caspar LEBHART Laser Standard YCB 112 1:03:39 0:56:49 14 (DNC) 0:46:18 0:41:20 11 0:34:58 0:31:13 10 64 35 204060 11 SUI 91 Patrik MUSTER Finn YCB 109 0:55:36 0:51:00 8 (DNC) 0:41:51 0:38:23 -

History of Sailing at the Olympic Games

OSC REFERENCE COLLECTION SAILING History of Sailing at the Olympic Games 19.10.2017 SAILING History of Sailing at the Olympic Games SAILING Paris 1900 Los Angeles 1984 Sydney 2000 Rio 2016 2-3t (Mixed) Flying dutchman (Mixed) Laser (Men) Nacra 17 (Mixed) INTRODUCTION Sailing was planned for the programme of the Games of the I Olympiad in Athens in 1896, but the events were not staged owing to the bad weather. It was then staged for each edition of the Games with the exception of those in St Louis in 1904. Women competed in the mixed sailing events as of 1900. Since the Games of the XXIV Olympiad in Seoul in 1988, some events have been reserved only for them. KEY STAGES Entry 1894: At the Paris Congress held in June, the desire was expressed for nautical sports (rowing, sailing and swimming) to be on the Olympic programme. Windsurfing 1980: At the 83rd IOC Session held in July and August in Moscow, it was decided to add a mixed windsurfing event (windglider) to the programme of the Games of the XXIII Olympiad in Los Angeles in 1984. Women’s 1984: At the IOC Executive Board meeting held in July and August in Los inclusion Angeles, it was decided to add the 470 dinghy event for women to the programme of the Games in Seoul in 1988. EVOLUTION IN THE NUMBER OF EVENTS 1900: 13 events (mixed) 1988: 8 events (1 men's, 1 women's, 6 mixed) 1908-1912: 4 events (mixed) 1992-1996: 10 events (3 men's, 3 women's, 4 mixed) 1920: 14 events (mixed) 2000: 11 events (3 men's, 3 women's, 5 mixed) 1924-1928: 3 events (mixed) 2004-2008: 11 events (4 men's, 4 -

Solo November 2019

Finn Clinic Fairhope YC - page 9 USA FINN CLASS November 2019 www.finnusa.org We are growing again!! National Class Contacts The effort kicked off years ago by Joe Chinburg and others is starting to pay off! We have new activity in many different areas of the country! In addition to the explo- Peter Frissell—President sion of activity in Southern California and the Rocky Mountain district we have new [email protected] activity in the Midwest. I credit both Mike Dorgan and Rodion Mazin for their social Rodion Mazin—Secretary media efforts and abilities. A few other areas where we are starting to see more ac- tivity; This past winter Joe Burke held some training sessions and the Nationals in [email protected] Sarasota. Rob Coutts is getting some people interested in Iowa on Lake Okoboji. Glenn Selvin—Treasurer We’ve had a number of successful regattas on the Great Lakes thanks to John [email protected] Woodruffs persistence a few years ago. Terry Greenfield—Chief Measurer James Bland is doing a great job of keeping things on track for the Nationals and North Americans and just held a great regatta in Austin. [email protected] Darrell Peck—Honorary President On the International front, the persistence of the IFA has resulted in a number of submissions in a last-ditch effort to get the Finn reinstated in the Olympics. Please [email protected] look at the IFA website for more information. To add additional fuel to the growth, the Class Officers has three projects in process. A modified loaner boat program is progressing.