PSA/NPEPPS): PSA/NPEPPS Is a Possible Modifier of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

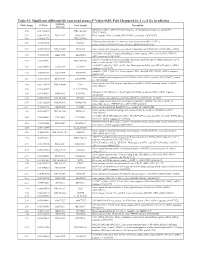

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Ykt6 Membrane-To-Cytosol Cycling Regulates Exosomal Wnt Secretion

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/485565; this version posted December 3, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Ykt6 membrane-to-cytosol cycling regulates exosomal Wnt secretion Karen Linnemannstöns1,2, Pradhipa Karuna1,2, Leonie Witte1,2, Jeanette Kittel1,2, Adi Danieli1,2, Denise Müller1,2, Lena Nitsch1,2, Mona Honemann-Capito1,2, Ferdinand Grawe3,4, Andreas Wodarz3,4 and Julia Christina Gross1,2* Affiliations: 1Hematology and Oncology, University Medical Center Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany. 2Developmental Biochemistry, University Medical Center Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany. 3Molecular Cell Biology, Institute I for Anatomy, University of Cologne Medical School, Cologne, Germany 4Cluster of Excellence-Cellular Stress Response in Aging-Associated Diseases (CECAD), Cologne, Germany *Correspondence: Dr. Julia Christina Gross, Hematology and Oncology/Developmental Biochemistry, University Medical Center Goettingen, Justus-von-Liebig Weg 11, 37077 Goettingen Germany Abstract Protein trafficking in the secretory pathway, for example the secretion of Wnt proteins, requires tight regulation. These ligands activate Wnt signaling pathways and are crucially involved in development and disease. Wnt is transported to the plasma membrane by its cargo receptor Evi, where Wnt/Evi complexes are endocytosed and sorted onto exosomes for long-range secretion. However, the trafficking steps within the endosomal compartment are not fully understood. The promiscuous SNARE Ykt6 folds into an auto-inhibiting conformation in the cytosol, but a portion associates with membranes by its farnesylated and palmitoylated C-terminus. Here, we demonstrate that membrane detachment of Ykt6 is essential for exosomal Wnt secretion. -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

Modeling of Human M1 Aminopeptidases for in Silico Screening of Potential Plasmodium Falciparum Alanine Aminopeptidase (Pfa-M1) Specific Inhibitors

open access www.bioinformation.net Hypothesis Volume 10(8) Modeling of human M1 aminopeptidases for in silico screening of potential Plasmodium falciparum alanine aminopeptidase (PfA-M1) specific inhibitors Shakti Sahi*, Sneha Rai, Meenakshi Chaudhary & Vikrant Nain* School of Biotechnology, Gautam Buddha University, Greater Noida, 201312, India; Shakti Sahi – Email: [email protected]; Vikrant Nain- Email: [email protected]; Phone: +91-120-234275; +91-120-234283 Fax: +91-120-234205; *Corresponding authors Received June 18, 2014; Accepted June 27, 2014; Published August 30, 2014 Abstract: Plasmodium falciparum alanine M1-aminopeptidase (PfA-M1) is a validated target for anti-malarial drug development. Presence of significant similarity between PfA-M1 and human M1-aminopeptidases, particularly within regions of enzyme active site leads to problem of non-specificity and off-target binding for known aminopeptidase inhibitors. Molecular docking based in silico screening approach for off-target binding has high potential but requires 3D-structure of all human M1-aminopeptidaes. Therefore, in the present study 3D structural models of seven human M1-aminopeptidases were developed. The robustness of docking parameters and quality of predicted human M1-aminopeptidases structural models was evaluated by stereochemical analysis and docking of their respective known inhibitors. The docking scores were in agreement with the inhibitory concentrations elucidated in enzyme assays of respective inhibitor enzyme combinations (r2≈0.70). Further docking analysis of fifteen potential PfA-M1 inhibitors (virtual screening identified) showed that three compounds had less docking affinity for human M1-aminopeptidases as compared to PfA-M1. These three identified potential lead compounds can be validated with enzyme assays and used as a scaffold for designing of new compounds with increased specificity towards PfA-M1. -

Goat Anti-MP100 / NPEPPS Antibody Peptide-Affinity Purified Goat Antibody Catalog # Af1679a

10320 Camino Santa Fe, Suite G San Diego, CA 92121 Tel: 858.875.1900 Fax: 858.622.0609 Goat Anti-MP100 / NPEPPS Antibody Peptide-affinity purified goat antibody Catalog # AF1679a Specification Goat Anti-MP100 / NPEPPS Antibody - Product Information Application WB Primary Accession P55786 Other Accession NP_006301, 9520 Reactivity Human Predicted Mouse, Rat Host Goat Clonality Polyclonal Concentration 100ug/200ul Isotype IgG Calculated MW 103276 AF1679a (0.3 µg/ml) staining of Human Brain Goat Anti-MP100 / NPEPPS Antibody - Additional (Cerebral Cortex) lysate (35 µg protein in Information RIPA buffer). Primary incubation was 1 hour. Detected by chemiluminescence. Gene ID 9520 Other Names Goat Anti-MP100 / NPEPPS Antibody - Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, PSA, Background 3.4.11.14, Cytosol alanyl aminopeptidase, AAP-S, NPEPPS, PSA This gene encodes the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, a zinc metallopeptidase which Format hydrolyzes amino acids from the N-terminus of 0.5 mg IgG/ml in Tris saline (20mM Tris its substrate. The protein has been localized to pH7.3, 150mM NaCl), 0.02% sodium azide, both the cytoplasm and to cellular membranes. with 0.5% bovine serum albumin This enzyme degrades enkaphalins in the brain, and studies in mouse suggest that it is Storage involved in proteolytic events regulating the Maintain refrigerated at 2-8°C for up to 6 cell cycle. months. For long term storage store at -20°C in small aliquots to prevent Goat Anti-MP100 / NPEPPS Antibody - freeze-thaw cycles. References Precautions Involvement of puromycin-sensitive Goat Anti-MP100 / NPEPPS Antibody is for aminopeptidase in proteolysis of tau protein in research use only and not for use in cultured cells, and attenuated proteolysis of diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. -

1 Large-Scale Deep Multi-Layer Analysis of Alzheimer's Disease

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.05.438450; this version posted August 13, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Large-Scale Deep Multi-Layer Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Reveals Strong Proteomic Disease-Related Changes Not Observed at the RNA Level Erik C.B. Johnson1,2,†,*, E. Kathleen Carter1,2,†, Eric B. Dammer1,3,†, Duc M. Duong1,3, Ekaterina S. Gerasimov2, Yue Liu4, Jiaqi Liu4, Ranjita Betarbet1,2, Lingyan Ping1,2,3, Luming Yin3, Geidy E. Serrano7, Thomas G. Beach7, Junmin Peng8,9, Philip L. De Jager10, Vahram Haroutunian11,12, Bin Zhang13, Chris Gaiteri14, David A. Bennett14, Marla Gearing1,2,6, Thomas S. Wingo1,2,4, Aliza P. Wingo1,5,15, James J. Lah1,2, Allan I. Levey1,2,* and Nicholas T. Seyfried1,2,3,* 1Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA 2Department of Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA 3Department of Biochemistry, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA 4Department of Genetics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA 5Department of Psychiatry, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA 6Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA 7Banner Sun Health Research Institute, Sun City, AZ, USA 8Departments of Structural Biology and Developmental Neurobiology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA 9Center for Proteomics and Metabolomics, St. -

Proteomic Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles Derived From

cells Article Proteomic Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Cerebrospinal Fluid of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: A Pilot Study Satoshi Muraoka 1, Mark P. Jedrychowski 2, Kiran Yanamandra 3, Seiko Ikezu 1, Steven P. Gygi 2 and Tsuneya Ikezu 1,4,5,* 1 Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02118, USA; [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (S.I.) 2 Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA; [email protected] (M.P.J.); [email protected] (S.P.G.) 3 Abbvie Inc. Foundational Neuroscience Center, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02118, USA 5 Center for Systems Neuroscience, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-617-358-9575 Received: 26 June 2020; Accepted: 21 August 2020; Published: 25 August 2020 Abstract: Pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are deposits of amyloid beta (Aβ) and hyper-phosphorylated tau aggregates in brain plaques. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of Aβ and tau-containing extracellular vesicles (EVs) in AD. We therefore examined EVs separated from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and control (CTRL) patient samples to profile the protein composition of CSF EV. EV fractions were separated from AD (n = 13), MCI (n = 10), and CTRL (n = 10) CSF samples using MagCapture Exosome Isolation kit. The CSF-derived EV proteins were identified and quantified by label-free and tandem mass tag (TMT)-labeled mass spectrometry. -

NPEPPS (NM 006310) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product Data

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for RC209037 NPEPPS (NM_006310) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product data: Product Type: Expression Plasmids Product Name: NPEPPS (NM_006310) Human Tagged ORF Clone Tag: Myc-DDK Symbol: NPEPPS Synonyms: AAP-S; MP100; PSA Vector: pCMV6-Entry (PS100001) E. coli Selection: Kanamycin (25 ug/mL) Cell Selection: Neomycin This product is to be used for laboratory only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. View online » ©2021 OriGene Technologies, Inc., 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200, Rockville, MD 20850, US 1 / 5 NPEPPS (NM_006310) Human Tagged ORF Clone – RC209037 ORF Nucleotide >RC209037 representing NM_006310 Sequence: Red=Cloning site Blue=ORF Green=Tags(s) TTTTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGGCCGGGAATTCGTCGACTGGATCCGGTACCGAGGAGATCTGCC GCCGCGATCGCC ATGTGGCTGGCAGCTGCCGCCCCCTCCCTCGCTCGCCGCCTGCTCTTCCTCGGCCCTCCGCCTCCTCCCC TCCTCCTTCTCGTCTTCAGCCGCTCCTCTCGCCGCCGCCTCCACAGCCTGGGCCTCGCCGCGATGCCGGA GAAGAGGCCCTTCGAGCGGCTGCCTGCCGATGTCTCCCCCATCAACTACAGCCTTTGCCTCAAGCCCGAC TTGCTGGACTTCACCTTCGAGGGCAAGCTGGAGGCCGCCGCCCAGGTGAGGCAGGCGACTAATCAGATTG TGATGAATTGTGCTGATATTGATATTATTACAGCTTCATATGCACCAGAAGGAGATGAAGAAATACATGC TACAGGATTTAACTATCAGAATGAAGATGAAAAAGTCACCTTGTCTTTCCCTAGTACTCTGCAAACAGGT ACGGGAACCTTAAAGATAGATTTTGTTGGAGAGCTGAATGACAAAATGAAAGGTTTCTATAGAAGTAAAT ATACTACCCCTTCTGGAGAGGTGCGCTATGCTGCTGTAACACAGTTTGAGGCTACTGATGCCCGAAGGGC TTTTCCTTGCTGGGATGAGCCTGCTATCAAAGCAACTTTTGATATCTCATTGGTTGTTCCTAAAGACAGA -

Aminopeptidase Expression in Multiple Myeloma Associates with Disease Progression and Sensitivity to Melflufen

cancers Article Aminopeptidase Expression in Multiple Myeloma Associates with Disease Progression and Sensitivity to Melflufen Juho J. Miettinen 1,† , Romika Kumari 1,†, Gunnhildur Asta Traustadottir 2 , Maiju-Emilia Huppunen 1, Philipp Sergeev 1, Muntasir M. Majumder 1, Alexander Schepsky 2 , Thorarinn Gudjonsson 2 , Juha Lievonen 3, Despina Bazou 4, Paul Dowling 5, Peter O‘Gorman 4, Ana Slipicevic 6, Pekka Anttila 3, Raija Silvennoinen 3 , Nina N. Nupponen 6, Fredrik Lehmann 6 and Caroline A. Heckman 1,* 1 Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland-FIMM, HiLIFE–Helsinki Institute of Life Science, iCAN Digital Precision Cancer Medicine Flagship, University of Helsinki, 00290 Helsinki, Finland; juho.miettinen@helsinki.fi (J.J.M.); romika.kumari@helsinki.fi (R.K.); maiju-emilia.huppunen@helsinki.fi (M.-E.H.); philipp.sergeev@helsinki.fi (P.S.); muntasir.mamun@helsinki.fi (M.M.M.) 2 Stem Cell Research Unit, Biomedical Center, University of Iceland, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland; [email protected] (G.A.T.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (T.G.) 3 Department of Hematology, Helsinki University Hospital Comprehensive Cancer Center, 00290 Helsinki, Finland; juha.lievonen@hus.fi (J.L.); pekka.anttila@hus.fi (P.A.); raija.silvennoinen@helsinki.fi (R.S.) 4 Department of Hematology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, D07 Dublin, Ireland; [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (P.O.) 5 Department of Biology, Maynooth University, National University of Ireland, Citation: Miettinen, J.J.; Kumari, R.; W23 F2H6 Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland; [email protected] Traustadottir, G.A.; Huppunen, M.-E.; 6 Oncopeptides AB, 111 53 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] (A.S.); Sergeev, P.; Majumder, M.M.; [email protected] (N.N.N.); [email protected] (F.L.) Schepsky, A.; Gudjonsson, T.; * Correspondence: caroline.heckman@helsinki.fi; Tel.: +358-50-415-6769 † These authors equally contributed to this work. -

High-Resolution Radiation Hybrid Mapping of Human Chromosome

Swine Research Report, 2000 Animal Science Research Reports 2001 High-Resolution Radiation Hybrid Mapping of Human Chromosome 17 Genes to the Pig Genome Extends Gene Order Conservation with Pig Chromosome 12 and Limited Synteny with Pig Chromosome 2 X. W. Shi Iowa State University C. J. Fitzsimmons Iowa State University C. K. Tuggle Iowa State University C. Genêt Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique–Toulouse R. Prather University of Missouri–Columbia Recommended Citation Shi, X. W.; Fitzsimmons, C. J.; Tuggle, C. K.; Genêt, C.; Prather, R.; Whitworth, K.; and Green, J. A., "High-Resolution Radiation Hybrid Mapping of Human Chromosome 17 Genes to the Pig Genome Extends Gene Order Conservation with Pig Chromosome 12 and Limited Synteny with Pig Chromosome 2" (2001). Swine Research Report, 2000. 19. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/swinereports_2000/19 This report is brought to you for free and open access by the Animal Science Research Reports at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swine Research Report, 2000 by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/swinereports_2000 Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Animal Sciences Commons Extension Number: ASL R666 High-Resolution Radiation Hybrid Mapping of Human Chromosome 17 Genes to the Pig Genome Extends Gene Order Conservation with Pig Chromosome 12 and Limited Synteny with Pig Chromosome 2 Abstract A comparative study of human chromosome 17 (HSA17) and pig chromosome 12 (SSC12) and 2 (SSC2) was conducted using both somatic cell hybrid panel (SCHP) and radiation hybrid (RH) panel analysis. -

The Genetics, Structure and Function of the M1 Aminopeptidase Oxytocinase Subfamily and Their Therapeutic Potential in Immune-Mediated Disease T

Human Immunology 80 (2019) 281–289 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Human Immunology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/humimm The genetics, structure and function of the M1 aminopeptidase oxytocinase subfamily and their therapeutic potential in immune-mediated disease T Aimee L. Hansona,b, Craig J. Mortonc,d, Michael W. Parkerc,d, Darrell Bessetteb,e, ⁎ Tony J. Kennab,e, a University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia b Translational Research Institute, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia c Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia d Australian Cancer Research Foundation Rational Drug Discovery Centre, St. Vincent's Institute of Medical Research, Fitzroy, VIC, Australia e Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The oxytocinase subfamily of M1 aminopeptidases plays an important role in processing and trimming of Aminopeptidase peptides for presentation on major histocompatibility (MHC) Class I molecules. Several large-scale genomic Antigen presentation studies have identified association of members of this family of enzymes, most notably ERAP1 and ERAP2, with Autoimmunity immune-mediated diseases including ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis and birdshot chorioretinopathy. Much is Inhibitor now known about the genetics of these enzymes and how genetic variants alter their function, but how these variants contribute to disease remains largely unresolved. Here we discuss what is known about their structure and function and highlight some of the knowledge gaps that affect development of drugs targeting these en- zymes. 1. M1 aminopeptidase oxytocinase subfamily – protein structure disturbed in ways that lead to immune system evasion or to auto- and function immune reactions. -

The M1 Aminopeptidase NPEPPS Is a Novel Regulator of Cisplatin

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.04.433676; this version posted March 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The M1 aminopeptidase NPEPPS is a 2 novel regulator of cisplatin sensitivity 3 4 Robert T. Jones1,15, Andrew Goodspeed1,3,15, Maryam C. Akbarzadeh2,4,16, Mathijs Scholtes2,16, 5 Hedvig Vekony1, Annie Jean1, Charlene B. Tilton1, Michael V. Orman1, Molishree Joshi1,5, 6 Teemu D. Laajala1,6, Mahmood Javaid7, Eric T. Clambey8, Ryan Layer7,9, Sarah Parker10, 7 Tokameh Mahmoudi2,11, Tahlita Zuiverloon2,*, Dan Theodorescu12,13,14,*, James C. Costello1,3,* 8 9 1Department of Pharmacology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, 10 USA 11 2 Department of Urology, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Erasmus University Medical Center 12 Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 13 3University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Colorado Anschutz 14 Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, USA 15 4Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center of Excellence, Tehran University of Medical 16 Sciences, Tehran, Iran 17 5Functional Genomics Facility, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, 18 USA 19 6Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Turku, Turku, Finland. 20 7Computer Science Department, University of Colorado, Boulder 21 8Department of Anesthesiology, University