Accessing Water for Domestic Use: the Challenges Faced in the Ga West Municipality, Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Care and Infrastructure in Accra, Ghana

Health Care and Infrastructure in Accra, Ghana Jennifer L. Pehr Advanced Issues in Urban Planning 27 April 2010 Page 1 of 21 Introduction Ghana, located in West Africa, was the first of the colonized countries in Africa to declare its independence. Accra is Ghana‟s capital city, and serves as the geographic and economic gateway to this region. The city‟s diverse economy is home to both local and regional traders as well as many international companies. Since its independence, Accra‟s population has increased rapidly. In 1957, the city had a population of approximately 190,000 (Grant &Yankson, 2003); today, the city‟s population is estimated to be over three million (Millennium Cities Initiative website). Accra experienced a period of rapid spatial expansion in the 1980s, and has been urbanizing rapidly ever since. Much of the city‟s growth has not been planned, and as a result, Accra‟s spatial expansion in recent years has occurred in some of the poorest areas of the city. This unfettered and unplanned growth has had severe implications for the population of Accra, and is most pronounced in the lack of basic urban infrastructure, including water and sanitation, transportation, education and health care in many parts of the city. In January 2010, Accra partnered with the Millennium Cities Initiative (MCI) to become a “Millennium City.” MCI works with underserved urban areas in sub-Saharan Africa to help them eradicate extreme poverty and to attain the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (MCI website). To fully realize a city‟s social and economic potential, needs assessments are conducted in many areas, including education, gender, water and sanitation, health and opportunities for economic development and foreign direct investment. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2007 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2007, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 51.500 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

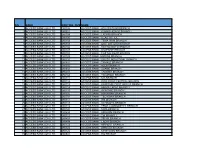

Certified Electrical Wiring Professionals Greater Accra Regional Register

CERTIFIED ELECTRICAL WIRING PROFESSIONALS GREATER ACCRA REGIONAL REGISTER NO NAME PHONE NUMBER PLACE OF WORK PIN NUMBER CERTIFICATION CLASS 1 ABABIO BENEDICT 0276904056 ACCRA EC/CEWP1/06/18/0001 DOMESTIC 2 ABABIO DONKOR DE-GRAFT 0244845008 ACCRA EC/CEWP2/06/18/0001 COMMERCIAL 3 ABABIO NICK OFOE KWABLAH 0244466671 ADA-FOAH EC/CEWP1/06/19/0002 DOMESTIC 4 ABABIO RICHARD 0244237329 ACCRA EC/CEWP3/06/17/001 INDUSTRIAL 5 ABAITEY JOHN KWAME 0541275499 TEMA EC/CEWP2/12/18/0002 COMMERCIAL 6 ABAKAH JOHN YAW 0277133971 ACCRA EC/CEWP2/12/18/0003 COMMERCIAL 7 ABAKAH KOBBINA JOSEPH 0548026138 SOWUTOUM EC/CEWP1/12/19/0001 DOMESTIC 8 ABASS QUAYSON 0274233850 KASOA EC/CEWP1/06/18/0004 DOMESTIC 9 ABAYATEYE NOAH 0243585563 AGOMEDA EC/CEWP2/12/18/0005 COMMERCIAL 10 ABBAM ERIC YAW 0544648580 ACCRA EC/CEWP2/06/15/0001 COMMERCIAL 11 ABBAN FRANCIS KWEKU 0267777333 ACCRA EC/CEWP3/12/17/0001 INDUSTRIAL 12 ABBAN KWABENA FRANCIS 0244627894 ACCRA EC/CEWP2/12/15/0001 COMMERCIAL 13 ABBEY DENNIS ANERTEY 0549493607 OSU EC/CEWP1/12/19/0002 DOMESTIC 14 ABBEY GABRIEL 0201427502 ASHIAMAN EC/CEWP1/06/19/0006 DOMESTIC 15 ABBEY LLOYD SYDNEY 0244727628 ACCRA EC/CEWP2/12/14/0001 COMMERCIAL 16 ABBEY PETER KWEIDORNU 0244684904 TESHIE EC/CEWP1/06/15/0004 DOMESTIC 17 ABBREY DAVID KUMAH 0244058801 ACCRA EC/CEWP2/06/14/0002 COMMERCIAL 18 ABDUL BACH ABDUL - MALIK 0554073119 ACCRA EC/CEWP1/06/18/0007 DOMESTIC 19 ABDUL HAMID AWUDU AMIDU 0242886030 TEMA,ACCRA EC/CEWP1/12/15/0005 DOMESTIC 20 ABDUL HAMID SANUSI 0243606097 DANSOMAN,ACCRA EC/CEWP1/12/15/0006 DOMESTIC 21 ABDUL HAMID SANUSI 0243606097 -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR11564 Implementation Status & Results Ghana Ghana Urban Transport Project (P100619) Operation Name: Ghana Urban Transport Project (P100619) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 13 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 16-Sep-2013 Country: Ghana Approval FY: 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 21-Jun-2007 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2012 Planned Mid Term Review Date 15-Apr-2010 Last Archived ISR Date 05-Jul-2013 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 19-Oct-2007 Revised Closing Date 15-Dec-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 16-Jan-2012 Project Development Objectives Ghana Urban Transport Project (P100619) Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The key objective of the project is to: Improve mobility in areas of participating metropolitan, municipal or district assemblies (MMDAs) through a combination of traffic engineering measures, management improvements, regulation of the public transport industry, and implementation of a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system. Public Disclosure Authorized Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Program? Yes No Ghana Urban Transport Project (P092509) Global Environmental Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The key objective is to: Promote a shift to more environmentally sustainable urban transport modes and encourage lower transport-related GHG emissions along the pilot BRT corridor -

Name Phone Number Location Certification Class 1 Akrofi

NAME PHONE NUMBER LOCATION CERTIFICATION CLASS 1 AKROFI EMMANUEL CUDJOE 0202002469 ACCRA COMMERCIAL 2 AMANOR PATRICK BEDIAKO 0243354280 ANYAA, ACCRA INDUSTRIAL 3 ABBAM ERIC YAW 0544461167 ACCRA COMMERCIAL 4 ABBAN KWABENA FRANCIS 0244627894 ACCRA COMMERCIAL 5 ABBEY LLOYD SYDNEY 0244727628 OSU COMMERCIAL 6 ABBEY PETER KWEIDORNU 0244684904 TESHIE DOMESTIC 7 ABBREY DAVID KUMAH 0244058801 ASHONGMAN, ACCRA COMMERCIAL 8 ABDUL HAMID AWUDU AMIDU 0242886030 TEMA,ACCRA DOMESTIC 9 ABDUL HAMID SANUSI 0243606097 DANSOMAN,ACCRA DOMESTIC 10 ABDUL RAMAN MUSTAPHA 0242939057 MAKOLA,ACCRA DOMESTIC 11 ABEDU RICHARD 0244258993 KANDA COMMERCIAL 12 ABEFE GIFTY 0277181938 ACCRA DOMESTIC 13 ABEW MAXWELL KOJO 0541921325 ODORKOR,ACCRA COMMERCIAL 14 ABLORNYI SOLOMON YAO 0244842620/0570742620 ACCRA DOMESTIC 15 ABOAGYE BENJAMIN KOJO KWADJO 0243733195 AJIRINGANO.ACCRA DOMESTIC 16 ABOAGYE GODFRED 0249565884 ACCRA COMMERCIAL 17 ABOAGYE RICHARD BOAFO 0244430975 ACCRA COMMERCIAL 18 ABOKUMA DANIEL KWABENA 0200196475 ACCRA COMMERCIAL 19 ABORTA EDEM BRIGHT 0244136035 MADINA,ACCRA DOMESTIC 20 ABOTSIGAH FRANK AGBENYO 0244447269 ZENU,ACCRA DOMESTIC 21 ABRAHAM JONATHAN 0208121757 TEMA COMMERCIAL 22 ABROQUAH ROMEL OKOAMPAH 0277858453 TEMA COMMERCIAL 23 ABUBAKARI ALI 0543289553 MADINA DOMESTIC 24 ACHAMPONG, ING KWAME AKOWUAH 0208159106 ABBOSSEY OKAI INDUSTRIAL 25 ACHEAMPONG EMMANUEL 0246971172 ACCRA COMMERCIAL 26 ACHEAMPONG EMMANUEL KWAMINA 0203003078 TAIFA, ACCRA DOMESTIC 27 ACHEAMPONG ROMEO 0247786202 TEMA NEW TOWN,ACCRA DOMESTIC 28 ACKAH ELORM KWAME 0243233564 ACCRA DOMESTIC -

Public Procurement Authority. Draft Entity Categorization List

PUBLIC PROCUREMENT AUTHORITY. DRAFT ENTITY CATEGORIZATION LIST A Special Constitutional Bodies Bank of Ghana Council of State Judicial Service Parliament B Independent Constitutional Bodies Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice Electoral Commission Ghana Audit Service Lands Commission Local Government Service Secretariat National Commission for Civic Education National Development Planning Commission National Media Commission Office of the Head of Civil Service Public Service Commission Veterans Association of Ghana Ministries Ministry for the Interior Ministry of Chieftaincy and Traditional Affairs Ministry of Communications Ministry of Defence Ministry of Education Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation Ministry of Finance Ministry Of Fisheries And Aquaculture Development Ministry of Food & Agriculture Ministry Of Foreign Affairs And Regional Integration Ministry of Gender, Children and Social protection Ministry of Health Ministry of Justice & Attorney General Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development Ministry of Petroleum Ministry of Power PUBLIC PROCUREMENT AUTHORITY. DRAFT ENTITY CATEGORIZATION LIST Ministry of Roads and Highways Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Creative Arts Ministry of Trade and Industry Ministry of Transport Ministry of Water Resources, Works & Housing Ministry Of Youth And Sports Office of the President Office of President Regional Co-ordinating Council Ashanti - Regional Co-ordinating -

Quality of Service Test Results for March 2018

QUALITY OF SERVICE TEST RESULTS FOR MARCH 2018 May, 2018 Table of Contents Quality of Service Monitoring Results for AirtelTigo ................................................................................. 2 Voice Test .......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 3G Data/Coverage Test ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Quality of Service Monitoring Results for Glo ................................................................................................ 8 Voice Test .......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 3G Data/Coverage Test .............................................................................................................................................. 9 Quality of Service Monitoring Results for MTN ........................................................................................... 14 Voice Test ........................................................................................................................................................................ 14 3G Data/Coverage Test ............................................................................................................................................ 15 Quality of -

Step 2 Compilation of the Sector Profile

MINISTRY OF ROADS & HIGHWAYS SECTOR MEDIUM-TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN (SMTDP): 2014-2017 DRAFT July, 2014 Road Sector SMTDP 2014-2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ...................................................................................................... i LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of figures .......................................................................................................................................... ii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................................. iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1 PROFILE AND CURRENT SITUATION .....................................................................................................3 1.1 Background............................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Sector Governance ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Review of Sector Policy Objectives and performance as linked to GSGDA -

Report of the Auditor General on the Accounts of District Assemblies For

Our Vision Our Vision is to become a world-class Supreme Audit I n s t i t u t i o n d e l i v e r i n g professional, excellent and cost-effective services. REPUBLIC OF GHANA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT ASSEMBLIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 This report has been prepared under Section 11 of the Audit Service Act, 2000 for presentation to Parliament in accordance with Section 20 of the Act. Johnson Akuamoah Asiedu Acting Auditor General Ghana Audit Service 21 October 2020 This report can be found on the Ghana Audit Service website: www.ghaudit.org For further information about the Ghana Audit Service, please contact: The Director, Communication Unit Ghana Audit Service Headquarters Post Office Box MB 96, Accra. Tel: 0302 664928/29/20 Fax: 0302 662493/675496 E-mail: [email protected] Location: Ministries Block 'O' © Ghana Audit Service 2020 TRANSMITTAL LETTER Ref. No.: AG//01/109/Vol.2/144 Office of the Auditor General P.O. Box MB 96 Accra GA/110/8787 21 October 2020 Tel: (0302) 662493 Fax: (0302) 675496 Dear Rt. Honourable Speaker, REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT ASSEMBLIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 I have the honour, in accordance with Article 187(5) of the Constitution to present my Report on the audit of the accounts of District Assemblies for the financial year ended 31 December 2019, to be laid before Parliament. 2. The Report is a consolidation of the significant findings and recommendations made during our routine audits, which have been formally communicated in management letters and annual audit reports to the Assemblies. -

Osu Watson Branch 2 Access Bank

S/N BANK ROUTING_NUMBERNAME 1 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280105 ACCESS BANK - OSU WATSON BRANCH 2 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280601 ACCESS BANK - KUMASI ASAFO BRANCH 3 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280104 ACCESS BANK - LASHIBI BRANCH 4 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280100 ACCESS BANK - HEAD OFFICE 5 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280102 ACCESS BANK - TEMA MAIN BRANCH 6 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280103 ACCESS BANK - OSU OXFORD BRANCH 7 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280106 ACCESS BANK - KANTAMANTO BRANCH 8 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280107 ACCESS BANK - KANESHIE BRANCH 9 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280108 ACCESS BANK - CASTLE ROAD BRANCH 10 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280109 ACCESS BANK -MADINA BRANCH 11 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280110 ACCESS BANK - SOUTH INDUSTRIAL BRANCH 12 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280801 ACCESS BANK - TAMALE BRANCH 13 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280602 ACCESS BANK - ADUM BRANCH 14 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280603 ACCESS BANK - SUAME BRANCH 15 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280401 ACCESS BANK - TARKWA BRANCH 16 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280402 ACCESS BANK - TAKORADI BRANCH 17 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280111 ACCESS BANK - NIA BRANCH 18 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280112 ACCESS BANK - RING ROAD CENTRAL BRANCH 19 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280113 ACCESS BANK - KANESHIE POST OFFICE BRANCH 20 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280114 ACCESS BANK - ABEKA LAPAZ BRANCH 21 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280115 ACCESS BANK - OKAISHIE BRANCH 22 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280116 ACCESS BANK - ASHAIMAN BRANCH 23 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280701 ACCESS BANK - TECHIMAN BRANCH 24 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280117 ACCESS BANK - IPS BRANCH 25 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280118 ACCESS BANK - ACHIMOTA BRANCH -

Seismological and Geological Investigation for Earthquake Hazard in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh SEISMOLOGICAL AND GEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION FOR EARTHQUAKE HAZARD IN THE GREATER ACCRA METROPOLITAN AREA This thesis is submitted to the DEPARTMENT OF NUCLEAR SCIENCES AND APPLICATIONS GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NUCLEAR AND ALLIED SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF GHANA BY MAXIMILLIAN-ROBERT SELORM DOKU 10362761 BSC PHYSICS (KNUST), 2007 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Award of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE in NUCLEAR EARTH SCIENCES JULY, 2013. University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I, Maximillian-Robert Selorm Doku hereby declare that, with the exception of references to other people’s works which have been duly acknowledged, this work is the result of my own research undertaken under the supervision of Dr. Paulina Ekua Amponsah and . Prof. Dickson Adomako and has not been presented for any other degree in this university or elsewhere, either in part or whole. …………………………….. ……..…………………… Maximillian-Robert Selorm Doku Date (Student) ……………………………. ….……………………… Dr. Paulina Ekua Amponsah Prof. Dickson Adomako Supervisor Co-Supervisor ……………………………. ……..…………………… Date Date i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my late mum, Esther Vugbagba. ii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to God Almighty for His guidance throughout this work. Secondly, my appreciation goes in no small way to my supervisors Dr. Paulina Ekua Amponsah and Prof. Dickson Adomako. They have been very inspiring and tolerant of my shortcomings. My sincere gratitude goes to my contemporaries and senior colleagues who have contributed in one way or the other to my work (School of Nuclear and Allied Sciences; Earth Sciences Department, University of Ghana and Ghana Atomic Energy Commission). -

Page 1 "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "J "

D I S T R I C T M A P O F G H A N A 3°0'0"W 2°30'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°30'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°30'0"W 0°0'0" 0°30'0"E 1°0'0"E B U R K I N A F A S O BAWKU MUNICIPAL Pusiga Zawli Hills Bawku J" J" Zawli Hills PUSIGA Uppe Bli 11°0'0"N Gwollu 11°0'0"N J" Paga Binduri Tapania Tributries J" J" Kulpawn H'Waters Ghira Navrongo North Zebilla Chasi BONGO Pudo J" BINDURI J"Bongo Nandom KASENA NANKANA WEST KN WEST Tumu Chana Hills J" Kambo Tumu Ü J" Garu NANDOM LAMBUSSIE KARNI Navrongo J" J" J" J" Nangodi SISSALA WEST BOLGATANGA BAWKU WEST Nandom Lambusie NABDAM GARU TEMPANE Bopong MUNICIPAL Polli KASENA NANKANA J" Sandema Bolgatanga J" EAST Tongo BUILSA NORTH J" TALENSI Kandembelli Lawra Sissili Central J" LAWRA SISSALA EAST Ankwai East Red & White Volta East Wiaga Red & White Volta east Wiaga Kandembelli Gambaga Scarp E&W JIRAPA Red & White Volta West Jirapa Gambaga J" J" Gbele Game Prod. resv. Mawbia J" 10°30'0"N 10°30'0"N BUILSA SOUTH Bunkpurugu Fumbisi Fumbesi " MAMPRUSI EAST Daffiama J BUNKPURUGU YONYO J" Pogi DAFFIAMA BUSSIE Nadawli WEST MAMPRUSI J" Gia J" Walewale Funsi NADOWLI-KALEO J" MAMPRUGU MOAGDURI Kulpawn Tributries J" Yagaba CHEREPONI Chereponi WA EAST J" Wa J" Nasia Tributries WA MUNICIPAL Ambalalai 10°0'0"N 10°0'0"N KARAGA Karanja Tanja J" GJ"USHIEGU Karaga R WA WEST Daka H'waters Wenchiau J" Nuale E KUMBUMGU SABOBA Sephe P NORTH GONJA J" SAVELUGU NANTON Saboba Mole National Park Savelugu J" U Kumbungu Daboya J" J" TOLON B 9°30'0"N SAWLA/TUNA/KALBA YENDI MUNICIPAL 9°30'0"N Bilisu Tolon SAGNERIGU Yendi Sagnarigu Sang J" J" J" Sinsableswani J" L J" Tamale Tatale TAMALE NORTH SUB METRO MION J" I C Zabzugu Sawla J" J" Dunwli O C TATALE T WEST GONJA Kani Kani ZABZUGU E Damongo Scarp J" Laboni Damongo Bole O J" 9°0'0"N 9°0'0"N NANUMBA NORTH F D' GONJA CENTRAL Kumbo Bimbila J" I Buipe T V J" Yakombo Lambo NANUMBA SOUTH BOLE O Wulensi O J" Yerada I G Salaga NKWANTA NORTH R J" Kpasa 8°30'0"N 8°30'0"N O E EAST GONJA Kpandai J" Bui Nat.