Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas Between the 8Th and 13Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VEIL of KASHMIR Poetry of Travel and Travail in Zhangzhungpa’S 15Th-Century Kāvya Reworking of the Biography of the Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo (958- 1055 CE)

VEIL OF KASHMIR Poetry of Travel and Travail in Zhangzhungpa’s 15th-Century Kāvya Reworking of the Biography of the Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo (958- 1055 CE) by Dan Martin n November of 1987, I visited Samten G. Karmay at his office, then on Rue du Président Wilson in Paris. With over twenty I years’ distance, and indeed that many years older, it is difficult to recall exactly what words were spoken during that meeting. As you get older you tend to look back on your past and identify particular turning points, discerning paths both taken and not taken. You are forced to become a historian of your own life. Suspended as I was in a veritable bardo between the incipient stages of that dreaded academic disease known as dissertationitis at a North American university and my second and longest sojourn in South Asia, I do not believe I was aware at the time just how important this meeting would be for setting me steadily on a course of research into 11th- and 12th-century Tibetan history, and especially the history of the Bon religion. In a word, it was inspirational. In 1996, the last week of June, I attended a conference in the Spiti valley, quite near the border with Tibet, in Himachal Pradesh. It was a very long and tiring but eventful three-day bus trip from Delhi via Simla and Kinnaur. This conference was intended as a millennial cele- bration for Tabo Monastery’s founding by Rinchen Zangpo in 996 CE. So needless to say, many of the papers were devoted to the Great Translator. -

The Tibetan Translation of the Indian Buddhist Epistemological Corpus

187 The Tibetan Translation of the Indian Buddhist Epistemological Corpus Pascale Hugon* As Buddhism was transmitted to Tibet, a huge number of texts were translated from Sanskrit, Chinese and other Asian languages into Tibetan. Epistemological treatises composed by In dian Buddhist scholars – works focusing on the nature of »valid cognition« and exploring peripheral issues of philosophy of mind, logic, and language – were, from the very beginning, part of the translated corpus, and had a profound impact on Tibetan intellectual history. This paper looks into the progression of the translation of such works in the two phases of the diffusion of Buddhism to Tibet – the early phase in the seventh to the ninth centuries and the later phase starting in the late tenth century – on the basis of lists of translated works in various catalogues compiled in these two phases and the contents of the section »epistemo logy« of canonical collections (Tenjur). The paper inquires into the prerogatives that directed the choice of works that were translated, the broader or narrower diffusion of existing trans lations, and also highlights preferences regarding which works were studied in particular contexts. I consider in particular the contribution of the famous »Great translator«, Ngok Loden Shérap (rngog blo ldan shes rab, 10591109), who was also a pioneer exegete, and discuss some of the practicalities and methodology in the translation process, touching on the question of terminology and translation style. The paper also reflects on the status of translated works as authentic sources by proxy, and correlatively, on the impact of mistaken translations and the strategies developed to avoid them. -

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE of LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much Ofwhat Is Generally Considered to Represent the Earl

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE OF LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much ofwhat is generally considered to represent the earliest heritage of Ladakh cannot be securely dated. It even cannot be said with certainty when Buddhism reached Ladakh. Similarly, much ofwhat is recorded in inscriptions and texts concerning the period preceding the establishment of the Ladakhi kingdom in the late 151h century is either fragmentary or legendary. Thus, only a comparative study of these records together 'with the architectural and artistic heritage can provide more secure glimpses into the early history of Buddhism in Ladakh. This study outlines the most crucial historical issues and questions from the point of view of an art historian and archaeologist, drawing on a selection of exemplary monuments and o~jects, the historical value of which has in many instances yet to be exploited. vVithout aiming to be so comprehensive, the article updates the ground breaking work of A.H. Francke (particularly 1914, 1926) and Snellgrove & Skorupski (1977, 1980) regarding the early Buddhist cultural heritage of the central region of Ladakh on the basis that the Alchi group of monuments l has to be attributed to the late 12 and early 13 th centuries AD rather than the 11 th or 12 th centuries as previously assumed (Goepper 1990). It also collects support for the new attribution published by different authors since Goepper's primary article. The nmv fairly secure attribution of the Alchi group of monuments shifts the dates by only one century} but has wide repercussions on I This term refers to the early monuments of Alchi, rvIangyu and Sumda, which are located in a narrow geographic area, have a common social, cultural and artistic background, and may be attIibuted to within a relatively narrow timeframe. -

Études Mongoles Et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques Et Tibétaines, 51 | 2020 the Murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a Few Related Monuments

Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 51 | 2020 Ladakh Through the Ages. A Volume on Art History and Archaeology, followed by Varia The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries Les peintures murales du Lotsawa Lhakhang de Henasku et de quelques temples apparentés. Un aperçu de la situation politico-religieuse du Ladakh aux XIVe et XVe siècles Nils Martin Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4361 DOI: 10.4000/emscat.4361 ISSN: 2101-0013 Publisher Centre d'Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études Electronic reference Nils Martin, “The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries”, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 51 | 2020, Online since 09 December 2020, connection on 13 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4361 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/emscat.4361 This text was automatically generated on 13 July 2021. © Tous droits réservés The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments.... 1 The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries Les peintures murales du Lotsawa Lhakhang de Henasku et de quelques temples apparentés. Un aperçu de la situation politico-religieuse du Ladakh aux XIVe et XVe siècles Nils Martin Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines, 51 | 2020 The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments... -

The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-Pa Formations

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-09-13 The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations Emory-Moore, Christopher Emory-Moore, C. (2012). The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28396 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/191 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-pa Formations by Christopher Emory-Moore A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2012 © Christopher Emory-Moore 2012 Abstract This thesis explores the adaptation of the Tibetan Buddhist guru/disciple relation by Euro-North American communities and argues that its praxis is that of a self-motivated disciple’s devotion to a perceptibly selfless guru. Chapter one provides a reception genealogy of the Tibetan guru/disciple relation in Western scholarship, followed by historical-anthropological descriptions of its practice reception in both Tibetan and Euro-North American formations. -

Rare and Important Manuscripts Found in Tibet

TIBETAN SCHOLARSHIP Rare and Important Manuscripts Found in Tibet By James Blumenthal he past few years has been an exciting time for scholars, Nyima Drak (b. 1055). Patsab Nyima Drak was the translator historians, and practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism as of Chandrakirti's writings into Tibetan and the individual Tdozens of forgotten and lost Buddhist manuscripts most responsible for the spread of the Prasangika- have been newly discovered in Tibet.' The majority of the Madhyamaka view in this early period. Included among this texts were discovered at Drepung monastery, outside of new discovery of Kadam writings are two of his original Lhasa, and at the Potala Palace, though there have been compositions: a commentary on Nagarjuna's Fundamental smaller groups of texts found elsewhere in the Tibet. The Wisdom of the Middle Way, and a commentary on Aryadeva's single greatest accumulation is the group of several hundred Four Hundred Stanzas on the Deeds of a Bodhisattva. Kadam texts dating from the eleventh to early fourteenth Perhaps the greatest Tibetan philosopher from this centuries that have been compiled and published in two sets period, and to this point, the missing link in scholarly under- of thirty pecha volumes (with another set of thirty due later standing of the historical development of Tibetan Buddhist this year). These include lojong (mind training) texts, thought was Chaba Chokyi Senge (1109-1169). This recent commentaries on a wide variety of Buddhist philosophical find produced sixteen previously lost or unknown texts by topics from Madhyamaka to pramana (valid knowledge) to Chaba including several important Madhyamaka and Buddha nature, and on cosmology, psychology and monastic pramana treatises. -

Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture by Ronald M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Macalester College Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 26 Number 1 People and Environment: Conservation and Article 17 Management of Natural Resources across the Himalaya No. 1 & 2 2006 Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture by Ronald M. Davidson; reviewed by Chris Haskett Chris Haskett Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Haskett, Chris (2006) "Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture by Ronald M. Davidson; reviewed by Chris Haskett," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 26: No. 1, Article 17. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol26/iss1/17 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. or part of the Chinese empire 7 Since the bibliography only available in mimeographed hand lists or well- excludes works in Chinese or Himalayan languages, thumbed card catalogs of specialized institutions. it is not clear that this question is answerable based Some bibliographies are migrating to the World on the works in the bibliography. However, it is Wide Web which holds the promise of a format that clear that Marshall's attention to the many English- is easily kept up-to-date. -

From Padmasambhava to Gö Tsangpa: Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas Between the 8Th and 13Th Centuries

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en dubbelklik nul hierna en zet 2 auteursnamen neer op die plek met and): Mein- ert and Sørensen _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas, 8th–13th c. _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas, 8th–13th c. 151 Chapter 6 From Padmasambhava to Gö Tsangpa: Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas between the 8th and 13th Centuries Verena Widorn 1 Introduction1 Authenticity—in all its various aspects2—seems to be one of the most re- quired criterions when analysing an object of art. The questions of authentic- ity of provenance and originality in particular are of major importance for western art historians. The interest in genuine workmanship, the knowledge of an exact date, and chronology keep scholars occupied in their search for prop- er timelines and the artistic lineages of monuments and artefacts. The time of 1 I especially wish to express my gratitude to Carmen Meinert and her team for the generous invitation to the start-up conference of her ERC project BuddhistRoad, which gave me the opportunity to present and now to publish a topic that has been on my mind for several years and was supported through several field trips to pilgrimage sites in Himachal Pradesh. Still, this study is just a first attempt to express my uneasiness with the manner in which academic studies forces western concepts of authenticity onto otherwise hagiographic ideals. I am also thankful to Max Deeg and Lewis Doney for their critical and efficient comments on my paper during the conference. -

View Profile

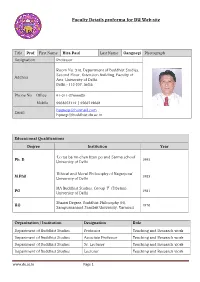

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected] Titl Profess First Hira Paul Last Gangnegi Photograph e or Name Name Designation PROFESSOR Address DEPARTMENT OF BUDDHIST STUDIES, FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF DELHI, DELHI-110007 Phone No +91-11-27666625 Office Residence C- 18, (29-31) Chatra Marg, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 Mobile +91-9560712608 Email [email protected] Web-Page www.du.ac.in Educational Qualifications Degree Title and Institution Year Ph.D. ‘Lotsaba Rinchen Zangpo and Sarma 1995 Schoo’. University of Delhi. M. Phil. ‘Ethical and Moral Philosophical of 1983 Nagarjuna’. University of Delhi. M. A. ‘Group (F) Tibetan Studies’. University of 1981 Delhi. Diploma in ‘Tibetan Language and Literature’. 1980 University of Delhi. Certificate in ‘Tibetan Language and Literature’. 1979 University of Delhi. B. A (Shastri) Sampurananda Sanskrit Viswavidayala, 1975 Varanasi. (UP). 1. Uttara Sampurnanda Sanskrit Viswavidayala, 1973 Madhyama Varanasi. (UP). 2. Purva 1971 Madhyama -Do- Career Profile 1. Former Head of Department, Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi from 01.03.2014 – 28.02.2017. (Ref.No: CNC-1/100/1988/BUDH ST/146) 2. Professor, Department of Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi from 1.07.2007 onwards. 3. Associate Professor/ Reader, Department of Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi from 27.07.1998 – 30.06.2007 4. Senior Lecturer, Department of Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi from 10.04.1990 - www.du.ac.in Page 1 26.07.1998. 5. Lecturer, Department of Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi from 09.04.1986 - 09.04.1990 6. -

Chakzampa Thangtong Gyalpo

Chakzampa Thangtong Gyalpo Architect, Philosopher and Iron Chain Bridge Builder Manfred Gerner Translated from German by Gregor Verhufen དཔལ་འག་ཞབ་འག་ི ེ་བ། Thangtong Gyalpo: Architect, Philosopher and Iron Chain Bridge Builder Copyright ©2007 the Centre for Bhutan Studies First Published: 2007 The Centre for Bhutan Studies PO Box No. 1111 Thimphu, Bhutan Tel: 975-2-321005, 321111 Fax: 975-2-321001 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.bhutanstudies.org.bt ISBN 99936-14-39-4 Cover photo: Statue of Drupthob Thangtong Gyalpo, believed to have been made by Drupthob himself, is housed in a private lhakhang of Tsheringmo, Pangkhar village, Ura, Bumthang. Photo by Karma Ura, 2007. Block print of Thangtong Gyalpo in title page by Lauf, 1972. To His Majesty, the Druk Gyalpo of the Royal Kingdom of Bhutan, the Bhutanese people and the Incarnation Line of Chakzampa Thangtong Gyalpo. ནད་མ་འོངམ་ལས་རིམ་ོ། ་མ་འོངམ་ལས་ཟམ། Appease the spirits before they turn foes Build a bridge before the river swells Contents Preface ......................................................................................i I. Biographical notes on Thangtong Gyalpo ...................... 1 The King of the Empty Plains.............................................................. 1 Tibet of his times.................................................................................... 6 Thangtong Gyalpo’s journeys to Bhutan ........................................... 8 Fragments from his life’s work.......................................................... 12 Incarnation lineage............................................................................. -

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche

KHYENTSE FOUNDATION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche. Photo by Pawo Choyning Dorji. Aspiration Prayer Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen (1292-1361), a great Tibetan master, wrote this prayer, which Rinpoche said we should recite as Khyentse Foundation’s aspiration: May I be reborn again and again, And in all my lives May I carry the weight of Buddha Shakyamuni’s teachings. And if I cannot bear that weight, At the very least, May I be born with the burden of thinking that the Buddhadharma may wane. 2 | KHYENTSE FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT KHYENTSE FOUNDATION’S ASPIRATION Excerpts from Rinpoche’s Address to the KF Board of Directors New York, October 22, 2016 irst of all, I have to rejoice about “As followers of Shakyamuni Buddha, what we have done. I think we the best thing that we can do is to pro- are supporting more than 2,500 tect and uphold his teachings, to keep monks and nuns and 1,500 lay them alive through studying and putting people, probably many more, them into practice.” helping all different lineages and traditions, not only — Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche the Tibetans. Khyentse Foundation has supported Fpeople from more than 40 different countries. We The longevity and the strength of the Dharma are so are also associated with 28 different universities. important because, if the Dharma becomes extinct, That is very worthy of rejoicing. then the source of the happiness, liberation, is fin- ished for all. Concern for the Dharma is bodhicitta. Of course, I don’t need to remind anyone that I don’t think there is any other greater bodhicitta Khyentse Foundation is not a materialistic, profit- — relative bodhicitta at least — than concern for oriented organization. -

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Prof. First Name Hira Paul Last Name Gangnegi Photograph Designation Professor Room No. 316, Department of Buddhist Studies, Second Floor, Extension Building, Faculty of Address Arts, University of Delhi, Delhi - 110 007, India Phone No Office 91-011-27666625 Mobile 9968053119 | 9560712608 [email protected] ; Email [email protected] Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year ‘Lo tsa ba rin chen bzan po and Sarma school’ Ph. D. 1995 University of Delhi ‘Ethical and Moral Philosophy of Nagarjuna’ M.Phil 1983 University of Delhi MA Buddhist Studies, Group ‘F’ (Tibetan), PG 1981 University of Delhi Shastri Degree, Buddhist Philosophy (H), UG 1976 Sampurnanand Sanskrit University, Varanasi Organization / Institution Designation Role Department of Buddhist Studies Professor Teaching and Research work Department of Buddhist Studies Associate Professor Teaching and Research work Department of Buddhist Studies Sr. Lecturer Teaching and Research work Department of Buddhist Studies Lecturer Teaching and Research work www.du.ac.in Page 1 Department of Buddhist Studies Lecturer (Ad-hoc) Teaching and Research work Administrative Assignments 1. Warden, Mansarovar Hostel, University of Delhi since May, 2007. 2. Member, Board of Buddhist Studies, Himachal University, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, 2008- 2010. 3. University Court Member, University of Delhi. 4. Member, Managing Committee, Gandhi Bhawan, University of Delhi. 5. Resident Tutor, PG Men’s Hostel, University of Delhi (1999-). 6. Member, Working Committee, Himachal Kala Sanskriti Evam Bhasha Academy, Himachal Pradesh. 7. University Observer, SC/ST & OBC Selection Committee, University of Delhi. 8. Member, Managing Committee, Ambedkar Ganguly Students House, University of Delhi. Areas of Interest / Specialization Buddhist Studies, History of Mahayana Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism & Tibetan Language and Literature.