Bringing an Icon Into the Future: Willis Tower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “International” Skyscraper: Observations 2. Journal Paper

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The “International” Skyscraper: Observations Author: Georges Binder, Managing Director, Buildings & Data SA Subject: Urban Design Keywords: Density Mixed-Use Urban Design Verticality Publication Date: 2008 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal, 2008 Issue I Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Georges Binder The “International” Skyscraper: Observations While using tall buildings data, the following paper aims to show trends and shifts relating to building use and new locations accommodating high-rise buildings. After decades of the American office building being dominate, in the last twelve years we have observed a gradual but major shift from office use to residential and mixed-use for Tall Buildings, and from North America to Asia. The turn of the millennium has also seen major changes in the use of buildings in cities having the longest experience with Tall Buildings. Chicago is witnessing a series of office buildings being transformed into residential or mixed-use buildings, a phenomenon also occurring on a large scale in New York. In midtown Manhattan of New York City we note the transformation of major hotels into residential projects. The transformation of landmark projects in midtown New York City is making an impact, but it is not at all comparable to the number of new projects being built in Asia. When conceiving new projects, we should perhaps bear in mind that, in due time, these will also experience major shifts in uses and we should plan for this in advance. -

READING and WRITING Intro

READING AND WRITING Intro Sabina Ostrowska Kate Adams with Wendy Asplin Christina Cavage HOW PRISM WORKS WATCH AND LISTEN 1 Video Setting the context Every unit begins with a video clip. Each video serves PREPARING TO WATCH 1 Work with a partner and answer the questions. ACTIVATING YOUR as a springboard for the unit and introduces the KNOWLEDGE 1 What are five things that you do every day? 2 What jobs do people in the mountains do? What do you think they do every day? topic in an engaging way. The clips were carefully 3 What jobs do people on islands do? What do you think they do every day? selected to pique students’ interest and prepare 4 What do you think is better, living in the mountains or living on an them to explore the unit’s topic in greater depth. As island? Why? 2 Match the sentences to the pictures (1–4) from the video. PREDICTING CONTENT they work, students develop key skills in prediction, USING VISUALS a The women wear colorful clothes. b The woman is caring for a plant. c There is a village on the island. comprehension, and discussion. d The man is catching food to eat. GLOSSARY coast (n) the land next to the ocean deep (adj) having a long distance from top to bottom, like the middle of the ocean culture (n) the habits and traditions of a country or group of people sweep (v) to clean, especially a floor, by using a broom or brush raise (v) to take care of from a young age 60 UNIT 3 SCANNING TO FIND WHILE READING INFORMATION 4 Scan the texts. -

Lbbert Wayne Wamer a Thesis Presented to the Graduate

I AN ANALYSIS OF MULTIPLE USE BUILDING; by lbbert Wayne Wamer A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering Lehigh University 1982 TABLE OF CCNI'ENTS ABSI'RACI' 1 1. INTRODlCI'ICN 2 2. THE CGJCEPr OF A MULTI-USE BUILDING 3 3. HI8rORY AND GRami OF MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS 6 4. WHY MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS ARE PRACTICAL 11 4.1 CGVNI'GJN REJUVINATICN 11 4. 2 EN'ERGY SAVIN CS 11 4.3 CRIME PREVENTIOO 12 4. 4 VERI'ICAL CANYOO EFFECT 12 4. 5 OVEOCRO'IDING 13 5. DESHN CHARACTERisriCS OF MULTI-USE BUILDINCS 15 5 .1 srRlCI'URAL SYSI'EMS 15 5. 2 AOCHITECI'URAL CHARACTERisriCS 18 5. 3 ELEVATOR CHARACTERisriCS 19 6. PSYCHOI..OCICAL ASPECTS 21 7. CASE srUDIES 24 7 .1 JOHN HANCOCK CENTER 24 7 • 2 WATER TOiVER PlACE 25 7. 3 CITICORP CENTER 27 8. SUMMARY 29 9. GLOSSARY 31 10. TABLES 33 11. FIGJRES 41 12. REFERENCES 59 VITA 63 iii ACKNCMLEI)(}IIENTS The author would like to express his appreciation to Dr. Lynn S. Beedle for the supervision of this project and review of this manuscript. Research for this thesis was carried out at the Fritz Engineering Laboratory Library, Mart Science and Engineering Library, and Lindennan Library. The thesis is needed to partially fulfill degree requirenents in Civil Engineering. Dr. Lynn S. Beedle is the Director of Fritz Laboratory and Dr. David VanHom is the Chainnan of the Department of Civil Engineering. The author wishes to thank Betty Sumners, I:olores Rice, and Estella Brueningsen, who are staff menbers in Fritz Lab, for their help in locating infonnation and references. -

Structural Developments in Tall Buildings: Current Trends and Future Prospects

© 2007 University of Sydney. All rights reserved. Architectural Science Review www.arch.usyd.edu.au/asr Volume 50.3, pp 205-223 Invited Review Paper Structural Developments in Tall Buildings: Current Trends and Future Prospects Mir M. Ali† and Kyoung Sun Moon Structures Division, School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA †Corresponding Author: Tel: + 1 217 333 1330; Fax: +1 217 244 2900; E-mail: [email protected] Received 8 May; accepted 13 June 2007 Abstract: Tall building developments have been rapidly increasing worldwide. This paper reviews the evolution of tall building’s structural systems and the technological driving force behind tall building developments. For the primary structural systems, a new classification – interior structures and exterior structures – is presented. While most representative structural systems for tall buildings are discussed, the emphasis in this review paper is on current trends such as outrigger systems and diagrid structures. Auxiliary damping systems controlling building motion are also discussed. Further, contemporary “out-of-the-box” architectural design trends, such as aerodynamic and twisted forms, which directly or indirectly affect the structural performance of tall buildings, are reviewed. Finally, the future of structural developments in tall buildings is envisioned briefly. Keywords: Aerodynamics, Building forms, Damping systems, Diagrid structures, Exterior structures, Interior structures, Outrigger systems, Structural performance, Structural systems, Tall buildings Introduction Tall buildings emerged in the late nineteenth century in revolution – the steel skeletal structure – as well as consequent the United States of America. They constituted a so-called glass curtain wall systems, which occurred in Chicago, has led to “American Building Type,” meaning that most important tall the present state-of-the-art skyscraper. -

An Overview of Structural & Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings

ctbuh.org/papers Title: An Overview of Structural & Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings Using Exterior Bracing & Diagrid Systems Authors: Kheir Al-Kodmany, Professor, Urban Planning and Policy Department, University of Illinois Mir Ali, Professor Emeritus, School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Subjects: Architectural/Design Structural Engineering Keywords: Structural Engineering Structure Publication Date: 2016 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 5 Number 4 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Kheir Al-Kodmany; Mir Ali International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of December 2016, Vol 5, No 4, 271-291 High-Rise Buildings http://dx.doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2016.5.4.271 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php An Overview of Structural and Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings Using Exterior Bracing and Diagrid Systems Kheir Al-Kodmany1,† and Mir M. Ali2 1Urban Planning and Policy Department, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL 60607, USA 2School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA Abstract There is much architectural and engineering literature which discusses the virtues of exterior bracing and diagrid systems in regards to sustainability - two systems which generally reduce building materials, enhance structural performance, and decrease overall construction cost. By surveying past, present as well as possible future towers, this paper examines another attribute of these structural systems - the blend of structural functionality and aesthetics. Given the external nature of these structural systems, diagrids and exterior bracings can visually communicate the inherent structural logic of a building while also serving as a medium for artistic effect. -

Read More and Download The

Case Study: Vista Tower, Chicago A New View, and a New Gateway, for Chicago Abstract Upon completion, Vista Tower will become Chicago’s third tallest building, topping out the Lakeshore East development, where the Chicago River meets Lake Michigan. Juliane Wolf will participate in the Session 7C panel discussion High-Rise Occupying a highly visible site on a north- Design Drivers: Now to 2069, on Jeanne Gang Juliane Wolf south view corridor within the city’s grid, and in Wednesday, 30 October. Vista Tower is the subject of the off-site close proximity to the Loop, the river, and the program on Thursday, Authors city’s renowned lakefront park system, this 31 October. Jeanne Gang, Founding Principal and Partner Juliane Wolf, Design Principal and Partner mixed-use supertall building with a porous Studio Gang 1520 West Division Street base is simultaneously a distinctive landmark Chicago, IL 60642 USA at the scale of the city and a welcoming connector at the ground plane. Clad in a t: +1 773 384 1212 gradient of green-blue glass and supported by a reinforced concrete structure, the e: [email protected] studiogang.com tower is composed of an interconnected series of stacked, frustum-shaped volumes that move rhythmically in and out of plane and extend to various heights. The Jeanne Gang, architect and MacArthur Fellow, is the Founding Principal and Partner of Studio tower is lifted off the ground plane at the center, creating a key gateway for Gang, an architecture and urban design practice headquartered in Chicago with offices in New York, pedestrians accessing the Riverwalk from Lakeshore East Park. -

Analysis of Technical Problems in Modern Super-Slim High-Rise Residential Buildings

Budownictwo i Architektura 20(1) 2021, 83-116 DOI: 10.35784/bud-arch.2141 Received: 09.07.2020; Revised: 19.11.2020; Accepted: 15.12.2020; Avaliable online: 09.02.2020 © 2020 Budownictwo i Architektura Orginal Article This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-SA 4.0 Analysis of technical problems in modern super-slim high-rise residential buildings Jerzy Szołomicki1, Hanna Golasz-Szołomicka2 1 Faculty of Civil Engineering; Wrocław University of Science and Technology; 27 Wybrzeże Wyspiańskiego st., 50-370 Wrocław; Poland, [email protected] 0000-0002-1339-4470 2 Faculty of Architecture; Wrocław University of Science and Technology; 27 Wybrzeże Wyspiańskiego St., 50-370 Wrocław; Poland [email protected] 0000-0002-1125-6162 Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to present a new skyscraper typology which has developed over the recent years – super-tall and slender, needle-like residential towers. This trend appeared on the construction market along with the progress of advanced struc- tural solutions and the high demand for luxury apartments with spectacular views. Two types of constructions can be distinguished within this typology: ultra-luxury super-slim towers with the exclusivity of one or two apartments per floor (e.g. located in Manhattan, New York) and other slender high-rise towers, built in Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Hong Kong, Bangkok, and Melbourne, among others, which have multiple apartments on each floor. This paper presents a survey of selected slender high-rise buildings, where structural improvements in tall buildings developed over the recent decade are considered from the architectural and structural view. -

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

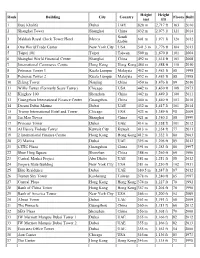

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

Burj Khalifa Tower

Burj Khalifa Tower The tallest structure in the world, standing at 2,722 ft (830 meters), just over 1/2 mile high, Burj Khalifa (Khalifa Tower) opened in 2010 as a centerpiece building in a large-scale, mixed-use development called Downtown Dubai. The building originally referred to as Dubai Tower was renamed in honor of the president of the United Arab Emirates, Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan. Burj Khalifa Dubai, United Arab Emirates Architecture Style Modern Skyscraper | Neo-Futurism Glass, Steel, Aluminum & Reinforced Concrete Prominent Architecture Features Y-Shaped Floor Plan Maximizes Window Perimeter Areas for residential and hotel space Buttressed central core and wing design to support the height of the building 27 setbacks in a spiraling pattern Main Structure 430,000 cubic yards reinforced concrete and 61,000 tons rebar Foundation - 59,000 cubic yards concrete and 192 piles 164 ft (50 m) deep Highly compartmentalized, pressurized refuge floors for life safety Facade Aluminum and textured stainless steel spandrel panels with low-E glass Vertical polished stainless steel fins Observation Deck - 148th Floor PROJECT SUMMARY Project Description Burj Kahlifa, the tallest building in the world, has redefined the possibilities in the design, engineering, and construction of mega-tall buildings. Incorporating periodic setbacks at the ends of each wing, the tower tapers in an upward spiraling pattern that decreases is mass as the height of the tower increases. The building’s design included multiple wind tunnel tests and design adjustments to develop optimum performance relative to wind and natural forces. The building serves as a model for the concept of future, compact, livable, urban centers with direct connections to mass transit systems. -

CASE STUDY WILLIS TOWER (Formerly Known As Sears Tower) Chicago, Illinois

CASE STUDY WILLIS TOWER (Formerly known as Sears Tower) Chicago, Illinois Situation Constructed in 1973 and named for its largest tenant, the 110-story Sears Tower was the tallest building in the world, a title it held for nearly 25 years. The Sears Tower featured 3,750,000 square feet of premier office, retail and restaurant space in addition to an observation deck and a rooftop antenna farm with over 52 broadcast users. After the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center in New York, the building’s then owner experienced a marked decrease in the desire for office space in the tallest building in the United States. This resulted in the property reverting to the lender, via a deed in lieu of foreclosure, further stigmatizing the building. Challenge/Opportunity In 2004, the property was purchased for $840 million, with occupancy at its lowest level in decades. American Landmark Properties and its principals were co-managing members of the ownership group and were involved in every aspect of renovating, rebranding, operating and managing this world-class property. The new ownership group saw an opportunity to acquire one of the truly iconic buildings in the world with a unique chance to restore the structure to its original world-famous status through a rebranding of the Tower and a physical and operational make-over, financed by a recapitalization. Results In 2015, the Willis Tower American Landmark Properties Solution sale to Blackstone Group Following the acquisition of the property, the new owners implemented a plan to rebrand the represented the highest price Tower, highlighting its prime location in the CBD and its state-of-the-art systems and security. -

The-Hows-Whats-And-Wows-Of-Willis

There are enough impressive facts about the When you get back to your school, we hope Willis Tower to make even the most worldly your students will send us photos or write or among us say, “Wow!” So many things at the create artwork about their experiences and Willis Tower can be described by a share them with us (via email or the mailing superlative: biggest, fastest, and longest. But address at the end of this guide). there is more to the building than all these “wows”: 1,450 sky-scraping, cloud-bumping One photo will be selected as the “Photo of feet of glass and steel, 43,000 miles of the Day” and displayed on our Skydeck telephone cable, 25,000 miles of plumbing, monitors for all to see. Artwork and writing 4.56 million square feet of floor space and a will posted on bulletin boards in the view of four states. lunchroom area. We would also love to have you and your students post you Skydeck Behind the “wows” are lots of “hows” and Chicago photos to the Skydeck Chicago pages “whats” for you and your students to on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. explore. In this guide you will be introduced to the building—its beginnings as the Sears As you get ready for your trip, please call us Tower and its design, construction and place with any questions at (312) 875-9447. We aim in the pantheon of skyscrapers. Its name to make your visit your best school trip ever. was recently changed to the Willis Tower, proudly reflecting the name of the global insurance broker who makes the Tower its Chicago home. -

Office Markets & Public Policy

REAL ESTATE ISSUES Office Markets REAL ESTATE ISSUES & Public Policy This is the first book that looks at how offices and office markets in cities have Also available in the series changed over the last 30 years. It analyses the long-term trends and processes Markets & Institutions in Real within office markets, and the interaction with the spatial economy and the Estate & Construction planning of cities. It draws on examples around the world, and looking forward Ball Policy Public & Markets Office at the future consequences of information communication technologies and the 9781405110990 sustainability agenda, it sets out the challenges that now face investors. The Right to Buy: Analysis & Evaluation of a Housing Policy The traditional business centres of cities are losing their dominance to the brash Jones & Murie new centres of the 1980s and 1990s, as the concept of the central business 9781405131971 district becomes more diffuse. Edge cities, business space and office parks have Housing Markets & Planning Policy entered the vocabulary as offices have also decentralised. The nature and pace of Jones & Watkins changes to office markets set within evolving spatial structures of cities has had 9781405175203 implications for tenants and led to a demand for shorter leases. The consequence is a rethink of the traditional perception of property investment as a secure long Challenges of the Housing Economy: An International Perspective term investment, and this is reflected in reduced investment holding periods by Jones, White & Dunse financial institutions. 9780470672334 Office Markets & Public Policy analyses these processes and policy issues from an Towers of Capital: Office Markets & international perspective and covers: International Financial Services Lizieri l A descriptive and theoretical base encompassing an historical context, 9781405156721 a review of the fundamentals of the demand for and supply of the office Office Markets market and offices as an investment.