International Pre-Electoral Observation Mission-Colombia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

126613844.23.Pdf

-Raj? Sds.m.s? PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIX PAPERS RELATING TO THE SCOTS IN POLAND November 1915 I v PAPERS RELATING TO THE SCOTS IN POLAND 1576-1798 Edited with an Introduction by A. FRANCIS STEUART ADVOCATE EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1915 PREFACE It is very necessary to present to the members of the Scottish History Society, in an apologetic vein, the disastrously chequered history of this very much belated book. The original intention of the Council was to issue Papers relating to the Scots in Poland, a collection made by and in part edited by Miss Beatrice Baskerville, and, as it was expected that this volume would be ready in 1907-1908, its title was accordingly placed among the Society’s publications for that year. Many and serious delays occurred, however : some were caused by the awkward climatic conditions of Poland, which render the transcribing of original documents by copyists almost impossible for many months of each year, other delays were caused by the difficulty of printing exactly (as was originally intended) the Manuscripts sent in Polish or Polish Latin transcriptions by not too accurate archivists. Losses of letters in the post, and changes in the secretariat of the Society further protracted matters. Then, as could not have been anticipated, the Balkan War arose, which distracted Miss Baskerville’s attention from her book to a more active Slavonic field. Lastly, the Polish and German literati engaged later to translate portions of this unlucky work were suddenly called off to fight in the great International War of 1914, and their places were only filled eventually by gracious volunteers, who bridged over by their kindness and labour yet another difficulty which could not have been foreseen. -

IFES Faqs on Elections in Colombia

Elections in Colombia 2018 Presidential Election Frequently Asked Questions Americas International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2011 Crystal Drive | Floor 10 | Arlington, VA 22202 | www.IFES.org May 14, 2018 Frequently Asked Questions When is Election Day? ................................................................................................................................... 1 Who are citizens voting for on Election Day? ............................................................................................... 1 When will the newly elected government take office? ................................................................................ 1 Who is eligible to vote?................................................................................................................................. 1 How many candidates are registered for the May 27 elections? ................................................................. 1 Who are the candidates? .............................................................................................................................. 1 How many registered voters are there? ....................................................................................................... 2 What is the structure of the government? ................................................................................................... 2 Are there any quotas in place? ..................................................................................................................... 3 What is the -

Elections in Colombia: 2014 Presidential Elections

Elections in Colombia: 2014 Presidential Elections Frequently Asked Questions Latin America and the Caribbean International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1850 K Street, NW | Fifth Floor | Washington, D.C. 20006 | www.IFES.org May 23, 2014 Frequently Asked Questions When is Election Day? ................................................................................................................................... 1 Who are citizens voting for on Election Day? ............................................................................................... 1 Who is eligible to vote?................................................................................................................................. 1 How many candidates are registered for the May 25 elections? ................................................................. 1 Who are the candidates running for President?........................................................................................... 1 How many registered voters are there? ....................................................................................................... 3 What is the structure of the government? ................................................................................................... 3 What is the gender balance within the candidate list? ................................................................................ 3 What is the election management body? What are its powers? ................................................................. 3 How many polling -

Colombia Baseline Study

RESPONSIBLE BUSINESS CONDUCT DUE DILIGENCE IN COLOMBIA’s golD SUPPLY CHAIN GOLD MINING IN CHOCÓ About the OECD The OECD is a forum in which governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people around the world. About the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Minerals The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Due Diligence Guidance) provides detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance is for use by any company potentially sourcing minerals or metals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. About this study This report is the third of a series of assessments on Colombian gold supply chains and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High- Risk Areas in the Colombian context. It analyses conditions of mineral extraction and related risks in Colombia’s Choco region. This report was prepared by Frédéric Massé and Jeremy McDermott, working as consultants for the OECD Secretariat. Find out more about OECD work on the minerals sector: mneguidelines.oecd.org/mining.htm Cofunded by the European Union © OECD 2017. This document is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

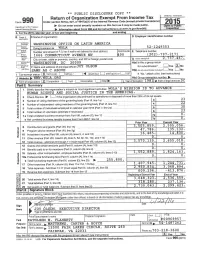

2015 IRS Form

Form 990 (2015) WASHINGTON OFFICE ON LATIN AMERICA 52-1249353 Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III †X 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission: WOLA'S MISSION IS TO ADVANCE HUMAN RIGHTS AND SOCIAL JUSTICE IN THE AMERICAS. 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ††Yes X No If "Yes," describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services?~~~~~~ ††Yes X No If "Yes," describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization's program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 514,393. including grants of $ )(Revenue $ ) HUMAN RIGHTS: WOLA IS A LEADING RESEARCH AND ADVOCACY ORGANIZATION ADVANCING HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE AMERICAS. WOLA SEEKS PUBLIC POLICIES IN THE AMERICAS THAT PROTECT HUMAN RIGHTS AND RECOGNIZE HUMAN DIGNITY, SO JUSTICE MAY OVERCOME VIOLENCE. WOLA TACKLES PROBLEMS THAT TRANSCEND BORDERS AND REQUIRE DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL SOLUTIONS. WOLA CREATES STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS WITH COURAGEOUS PEOPLE MAKING SOCIAL CHANGE-ADVOCACY ORGANIZATIONS, ACADEMICS, RELIGIOUS AND BUSINESS LEADERS, ARTISTS, AND POLICY MAKERS. TOGETHER, WE ADVOCATE FOR MORE JUST SOCIETIES IN THE AMERICAS. -

Mexico's Police: Many Reforms, Little Progress

esofoto C hez / Pro C án s nrique Castro nrique Castro e A convoy of Federal Police vehicles Credit: Photo passes through Morelia, the capital of Michoacán. Mexico's Police Many Reforms, Little Progress By Maureen Meyer For more than two decades, successive Mexican administrations have taken steps to create more professional, modern, and well-equipped police forces. While these reforms have included some positive elements, they have failed to establish strong internal and external controls over police actions, enabling a widespread pattern of abuse and corruption to continue. Recognizing the need for stronger controls over Mexico’s police, this report reviews Mexico’s police reforms, with a specific focus on accountability mechanisms, and provides recommendations for strengthening existing police reform efforts in order to establish rights-respecting forces that citizens can trust. WOLA Washington office on Latin america MAY 2014 2 Mexico's Police: Many Reforms, Little Progress Introduction now-defunct Ministry of Public Security (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública, SSP). The CNDH recommendation “Forgive us, this isn’t against you, it’s just that certified that the men had been arbitrarily detained those at the top are asking me for results.”1 and tortured. In early 2014, the Federal Attorney General’s OfficeProcuradur ( ía General de la On August 11, 2010, Rogelio Amaya Martínez, along República, PGR) used the international guidelines for with four other young men, was outside the house of the documentation of torture, known as the Istanbul a friend in Ciudad Juárez when two trucks of Federal Protocol, to examine all five men. Based on this Police agents drove by. -

Not a National Security Crisis

RESEARCH RESEARCH REPORT REPORT AP Photo/Eric Gay NOT A NATIONAL SECURITY CRISIS The U.S.-Mexico Border and Humanitarian Concerns, Seen from El Paso By Maureen Meyer, Adam Isacson, and Carolyn Scorpio OCTOBER 2016 Contrary to popular and political rhetoric about a national security crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border, evidence suggests a potential humanitarian—not security—emergency. This report, based on research and a field visit to El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico in April 2016, provides a dose of reality by examining one of the most emblematic of the U.S.- Mexico border’s nine sectors, one that falls within the middle of the rankings on migration, drug seizures, violence, and human rights abuses. NOT A NATIONAL SECURITY CRISIS The U.S.-Mexico Border and Humanitarian Concerns, Seen from El Paso TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 IMPORTANT CHANGES IN THE EL PASO SECTOR ...................................................... 12 NOTEWORTHY EFFORTS ON THE MEXICAN SIDE ................................................... 28 AREAS OF CONCERN ........................................................................................................................................32 RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................................................................................48 -

Vieques, a Target in the Sun

Vieques, a Target in the Sun By George Withers WOLA Senior Fellow for Regional Security Policy From 1943 until May 1, 2003, the U.S. Navy used portions of the island of Vieques, Puerto Rico for military training ranges and ammunitions storage. Ten years after the Navy left the island, the people of Vieques continue to suffer from poor health, high unemployment, a lack of basic services, and limited access to much of the land that was taken from them 60 years ago. May 2013 2 Vieques, a Target in the Sun INTRODUCTION THE NAVY AND VIEQUES “The abuse of the Empire has a limit and that is the In the early 1940s, the U.S. Navy began conducting patience of the people.” weapons training on the two islands off the east coast of Puerto Rico’s main island. But these two islands were not empty; each was occupied by local -Graffiti on Vieques civilians throughout the period that they were being used as targets for bombardment. President From a distance, Vieques looks like another Nixon in 1974 directed that weapons training on Caribbean island paradise with sandy beaches and Culebra be terminated, and in 1975, after more lush tropical forests. Sitting just off of the east coast than five years of protests by the inhabitants, Navy of Puerto Rico, and part of the Commonwealth, bombardment there stopped. This left the two target its population of fewer than 10,000 people lives ranges on Vieques, just south of Culebra, the only mostly in two villages, one on the north shore and ones in the Caribbean available for the training. -

Understanding the Deterioratin in US-Colombian Relations, 1995

UNDERSTANTING THE DETERIORATIN IN US-COLOMBIAN RELATIONS, 1995- 1997. CONFLICT AND COOPERATION IN THE WAR AGAINST DRUGS BY ALEXANDRA GUÁQUETA M. PHIL. THEIS SOMERVILLE COLLEGE, UNIVERISTY OF OXFORD APRIL, 1998 INTRODUCTION Colombia, unlike the majority of its Latin American and Caribbean neighbours, had a remarkable record of friendly relations with the United States throughout most of the twentieth century. However, this situation changed in 1995 when the U.S. downgraded Colombia's previous status of alliance in the war against illegal drugs by granting it a conditional certification (national interest waiver) on its performance in drug control.1 The drug certification is the annual process by which the U.S. evaluates other countries' accomplishments in drug control making foreign aid conditional to their degree of cooperation. It also involves economic sanctions when cooperation is deemed unsatisfactory. In 1996 and 1997 Bill Clinton's administration decertified Colombia completely. The media reported Colombia's 'Cuba-nisation' in Washington as U.S. policy makers became obsessed with isolating the Colombian president, Ernesto Samper.2 Colombia was officially branded as a 'threat to democracy' and to the U.S.3 1 See chapter 3 for detailed explanaition of certification. 2 Expression used by journalist Henry Raymount in Washington and quoted in El Tiempo, November 6, 1996, p. 11A. 3 U.S. Department of State, Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL), International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) 1997, Washington D.C., March 1997. p. xli. 1 Colombia and the U.S. quarrelled so severely that they perceived each other as enemies. 'Never before, had relations between the U.S. -

ECONOMIC 10 November 1962 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/SPANISH

UNITED NATI general E/CN.12/618 ECONOMIC 10 November 1962 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/SPANISH MiMiMMiMiummMMHNtnimiHiimMMitHiiiiitMtiHihnmHHMtiimmiiHMHMiiiiini ECONOMO COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA SOME ASPECTS OF POPULATION GROWTH IN COLOMBIA Prepared by the secretariat of the Economic Commission for Latin America E/CN,12/618 Page iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Sage Introduction. ............ ...»c..... 1 Population Estimates ..aoo.........•<>.o»... <,......... 3 1. Total population growth» «••.«•••»•a...*. 3 (a) The censuses of 1938 and 1.951 3 (b) Recent population growth in Ecuador, Mexico and 'Venezuela,, ........a...,,,», ...*<>«••...,, .,,,*«» 7 (c) Birth rates and death rates in Colombia 8 (d) Estimated population growth, 1945-70. ... 11 2. Population growth by departments ..... 14 (a) Growth of departmental populations according to census es osoo. 14 (b) Effects of migration 16 (c) Natural increase0.o * 21 (d) Population estimates for departments, 1945-70 23 3. Urban and rural populations,., 25 (a) Census definitions* 25 (b) The projection, 27 (c) Population of towns of various sizes* 29 (d) Urban and rural population by departments,,... • 34 II, Implications for education, manpower and housing,,..»., 41 1, Population and primary education0„ 9009 oe..'...«........... 41 (a) Children enrolled in primary schools.......... 41 (b) Number of children of proper primary school age...... 49 (c) Primary education: future requirements».,,..,,,...... 57 (d) Regional distribution of school children and school enrolment. o........... 62 (e) Educational level0.»....,.,.,........................ 66 (f) Literacy... 69 /2. Population and E/CN.12/618 Page iv £äge 2o Population and manpowers,..., <,.......» » 76 (a) Difficulty of study 76 (b) Economic activity of the population in 1951...* 77 (c) Reported economic activity of the population in 1938.... 80 (d) Effects of urbanization.. -

Localising the 2030 Agenda in Colombia

development dialogue paper no.25 | december 2018 Localising the 2030 Agenda in Colombia This paper describes Colombia’s process of localising the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It outlines the main steps taken in Colombia to mainstream and implement the Agenda as well as to follow up and communicate progress towards achieving the goals. The paper is based on official documents and interviews with selected national government representatives involved in these processes.1 It is intended to facilitate experience-sharing among governments and other actors seeking practical and successful ways to set up structures for the implementation of the SDGs. Introduction basis for Rio+20. Through dialogue, it managed to bring Colombia is a strong advocate and champion imple- together different positions and to gather a critical mass of menter of the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Develop- countries behind this proposal that gave rise to the com- ment Goals (SDGs). The country was active in the mitment to start building the 2030 Agenda. Following the process of developing and adopting the Agenda and Rio+20 agreement⁴, Colombia formed part of the Open has been a pioneer in localising and implementing it. Working Group set up to convene experts on various the- Its engagement with the Agenda coincides with a matic areas and to plot a route towards defining the global number of significant processes for the country. After a goals and targets. At national level, the Colombian Ministry five-year accession process, Colombia was formally of Foreign Affairs launched a work programme with differ- admitted to the Organisation for Economic Co- ent national government entities to coordinate negotiations operation and Development (OECD) in May 2018.