Cold War Nostalgia for Transnational Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deutschland 83 Is Determined to Stake out His Very Own Territory

October 3, 1990 – October 3, 2015. A German Silver Wedding A global local newspaper in cooperation with 2015 Share the spirit, join the Ode, you’re invited to sing along! Joy, bright spark of divinity, Daughter of Elysium, fire-inspired we tread, thy Heavenly, thy sanctuary. Thy magic power re-unites all that custom has divided, all men become brothers under the sway of thy gentle wings. 25 years ago, world history was rewritten. Germany was unified again, after four decades of separation. October 3 – A day to celebrate! How is Germany doing today and where does it want to go? 2 2015 EDITORIAL Good neighbors We aim to be and to become a nation of good neighbors both at home and abroad. WE ARE So spoke Willy Brandt in his first declaration as German Chancellor on Oct. 28, 1969. And 46 years later – in October 2015 – we can establish that Germany has indeed become a nation of good neighbors. In recent weeks espe- cially, we have demonstrated this by welcoming so many people seeking GRATEFUL protection from violence and suffer- ing. Willy Brandt’s approach formed the basis of a policy of peace and détente, which by 1989 dissolved Joy at the Fall of the Wall and German Reunification was the confrontation between East and West and enabled Chancellor greatest in Berlin. The two parts of the city have grown Helmut Kohl to bring about the reuni- fication of Germany in 1990. together as one | By Michael Müller And now we are celebrating the 25th anniversary of our unity regained. -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} This Must Be the Place by Anna Winger This Must Be the Place by Anna Winger

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} This Must Be the Place by Anna Winger This Must Be the Place by Anna Winger. "Ninety years is not such a long time in the scheme of things: the life of a person, if they are lucky; a room just wide enough to touch both walls with outstretched hands. In other places such a building might have seen only the soft swell of progress, but here? Ninety years of drama, followed only by this. " It is the autumn of 2001 in Berlin. In a once-grand building, on a forgotten corner of the city, an unlikely friendship is about to change two people's lives. Walter Baum is nearing forty. After a failed attempt to work as an actor in Hollywood sixteen years ago, he's been dubbing the lines of a famous American movie star into German, sitting in the dark, watching his bald spot and beer belly expand while his options and self-confidence diminish. In an identical apartment just downstairs, a young American woman named Hope rarely gets out of the bathtub. Having fled New York a month earlier to join her workaholic husband in Berlin, she is unable to cope with either the unfamiliar city around her or painful memories of the one she just left. When they meet by chance in the elevator, a sympathy develops, and then deepens, as together they begin to unravel secrets buried in the walls of their building and in their own personal histories. Against the backdrop of Berlin, a once-divided city in the process of reconstructing itself, Hope and Walter finally come to reconcile their hopes for the future with the ache of the past that lingers, permanently, beneath the surface. -

Issue # 164 20 September 2019 CANAL + Group and Netflix Team up to Offer Best of Movies and Series

04/08/2020 Media Weekly Broadcast Issue # 164 20 September 2019 CANAL + Group and Netflix team up to offer best of movies and series CANAL+ Group and Netflix announce a partnership under which the Netflix service will be included in CANAL+ bundles. Starting on October 15, CANAL+ subscribers to the CINE / SERIES package will have access to the CANAL+ premium channel as well as the Netflix The Association of Commercial services. Television in Europe (ACT) is a trade body for the commercial Read more broadcasting sector in Europe. Formed in 1989, the ACT has 27 member companies active in 37 European countries, operating and distributing several Mediaset hit record audience in summer thousand free-to-air and pay-tv channels and new media months and unveils upcoming programming services. Mediaset reached a peak audience in summer months, with an increase of more than 14% total audience share on its channels. Following these positive results Mediaset unveiled its new exclusive programming for the upcoming season, which features original content on the Group’s flagship channel Canale 5 every evening of the week. Mediaset’s CEO Pier Silvio Berlusconi confirmed the industrial and creative commitment of the Group and stated that “despite the difficult economic context we have been able to increase our original content offer and will close 2019 with positive economic results”. Read more NENT Group's original thriller `The Lawyer' returns for a second season oy99madskp.preview.infomaniak.website/oldsite/acte.be/_old/newsletters/172/50/Issue-164bf6b.html?cntnt01template=webversion-newsletter 1/3 04/08/2020 Media Weekly Broadcast Nordic Entertainment Group (NENT Group) has commissioned a second season of its hit original thriller ‘The Lawyer’, which was the most viewed original series on NENT Group’s Viaplay streaming service in 2018. -

TV, ECONOMICS & SOCIETY II STORIES for OUR TIME. Final Program. Monday 4 June 13.00 Optional Informal Lunch 14.45 Optional T

TV, ECONOMICS & SOCIETY II STORIES FOR OUR TIME. Final Program. Monday 4 June 13.00 Optional informal lunch 14.45 Optional tour of the WZB building 15.30 Coffee and Registration 16.00 Welcome and Introduction – Sir Peter Jonas and Steffen Huck 16.15 “Scientific Evidence on TV” – Joachim Winter 17.00 “Histories of Serial Story Telling: Europe and the US” – Gerhard Maier 17.45 “Behold, America” – Sarah Churchwell 19.00 Dinner Tuesday 5 June 10.30 “Two Views on Democracy: The West Wing and House of Cards” – Mattias Kumm 11.15 “The Third Golden Age: A Tale of Two Halves?” – Steffen Huck 12.00 “TV Soaps and Gender Violence: An Experiment in Uganda” – Jasper Cooper 12.45 Lunch Break 14.00 “Literature in the Times of Internet Platform Societies” -- Ernst-Wilhelm Händler 14.45 Coffee Break 15.15 “Making Stories” – Panel with Jenn Carroll, Frank Jastfelder, and Philip Voges 16.15 “European Perspectives” – Panel with Sascha Arango, Dennis Gansel, Nikolaj Scherfig and Anna Winger 17.30 Short Break 17.45 “Morality Plays” – Panel with Tom Fontana, Sir Peter Jonas, Gordon Smith and Bradford Winters 19.30 Dinner Participants Sascha Arango, the recipient of two Adolf-Grimme Prizes, is a script writer known and novelist. Jenn Carroll is Associate Producer of Better Call Saul. Jasper Cooper is a graduate student of political science at Columbia University in New York. Sarah Churchwell is Professor or American Literature and Public Understanding of the Humanities at the School of Advanced Study in London. Rachel Eggebeen is working for International Originals at Netflix. Tom Fontana, the recipient of three Emmy and four Peabody Awards, is a writer, showrunner, and producer. -

Anika Molnár Resume 2020

A N I K A M O L N Á R FOREWORD Anika Molnár is simply a brilliant photographer. Her range seems limitless… her eye is everywhere. I had the great pleasure to work with her on ‘Deutschland 86’ and the NETFLIX Mini-Series ‘Unorthodox’ and was again, and again surprised by the strength and depth of her photography. No matter if she works on sets with limited time or builds her own lavish setups, her work is always distinctive and stunning. Anika’s documentary work, her stills and – above all – her portraits magnify the moment and find the truth within beauty and beauty within the truth. Written by Maria Schrader Anika Molnár | Resume 2020 RECENT FILMOGRAPHY FEATURE FILMS TELEVISION SERIES (2016 – 2020) (2016 – 2020) Unorthodox~ Berlin & New York Kleiner Freund, Großer Freund Unit & Special Still Photographer Unit & Special Still Photographer Netflix / Studio Airlift / Real Film Berlin GmbH ZDF / Moviepool GmbH (Drama) (Drama) Director: Michael Karen Writer & Producer: Alexa Karolinski Cinematographer: Peter Krause Director: Maria Schrader Starring: Tanja Wedhorn, Stephan Luca, Likho Mango Cinematographer: Wolfgang Thaler Starring: Shira Haas, Amit Rahav, Jeff Wilbusch Der Weg Zum Kilimandscharo Unit & Special Still Photographer Deutschland 89 ~ Berlin & Leipzig ARD Degeto/Ariane Krampe Film GmbH Unit & Special Still Photographer (Adventure/Drama) UFA Fiction GmbH / Amazon Prime (Drama) Director: Gregor Schnitzler Creators: Jörg Winger & Anna Winger Cinematographer: Wolfgang Aichholzer Directors: Randa Chahoud & Soleen Yusef Starring: Anna Maria Mühe, Kostja Ullmann, Simon Cinematographer: Kristian Leschner & Stephan Schwarz Burchardt Starring: Jonas Nay, Svenja Jung, Maria Schrader, Florence Kasumba, Sylvester Groth, Corinna Harfouch Deutschland 86 ~ Cape Town & Berlin Unit & Special Still Photographer UFA Fiction GmbH / Amazon Prime (Drama) Showrunner: Debra Directors: Florian Cossen Cinematographer: Matthias Fleischer Starring: Jonas Nay, Maria Schrader, Florence Kasumba . -

Pass the Remote: 6 Women Shaping the Future of TV

Arts & Humanities Pass the Remote: 6 Women Shaping the Future of TV These directors, screenwriters, and producers — all with Columbia degrees — have found enviable success in the streaming era. By Julia Joy | Spring/Summer 2021 Bijou Karman Nicole Kassell Recent claim to fame: Watchmen Nicole Kassell ’94CC realized she was going to be a filmmaker during the first week of her freshman year at Columbia, when a classmate came into her dorm room and showed her a short film he had made. “It was a total lightning-strike moment,” says Kassell, now an accomplished director and producer who has worked on numerous television series, including Watchmen, The Leftovers, The Killing, and The Americans. “I knew I wanted to do that.” After studying art history at Columbia and film production at NYU, Kassell launched her career with The Woodsman, a daring indie feature starring Kevin Bacon as a convicted child molester trying to reenter society. The 2004 film generated buzz at the Sundance Film Festival, and Kassell began receiving invitations to direct episodes of crime and drama series like Cold Case and The Closer. At the time, there were fewer women filmmakers in the industry. “When I started, I was often the only female director on a series for that season. That’s rarely the case now,” she says. “Producers and writers are putting a lot more effort into making sure people of different genders and ethnicities are behind the camera.” Nicole Kassell (Bijou Karman) Kassell, who won a 2020 Emmy for outstanding limited series as an executive producer of Watchmen, says she is “drawn to stories that leave people thinking and growing.” She refuses to be boxed in by any one style or genre but admits she gravitates toward weighty subjects. -

Anomalia Beau Séjour

SÉRIE SERIES SPEAKERS GUIDE – SÉRIE SERIES 2015 ANOMALIA PIERRE MONNARD – DIRECTOR – SWITZERLAND During his films studies in England, Pierre began his career as a director with his shorts films Swapped and Come Closer. Praised internationally, his films won more than twenty awards, including the Prix du Cinéma Suisse and the Léopard du Meilleur Court-Métrage at the Locarno Festival. After this success, Pierre directed adverts and music videos across Europe. His campaigns for MTV, Stella Artois and Carambar as well as his work with the French singer Calogero, have won numerous awards. In 2013, Pierre moves onto film direction, with his quirky comedy, Recycling Lily, which was critically acclaimed and won the Lauréat of the Fünf Seen Festival in Germany. Pierre is currently working on Anomalia with actors Natacha Régnier and Didier Bezace. The broadcasting of this fantasy series about the world of healers is expected for the beginning of 2016. JEAN-MARC FRÖHLE – PRODUCER, POINT PROD – SWITZERLAND Founded in 1996, Point Prod specialises in all types of production (dramas, documentaries, topical shows, magazines, TV, news). In 2005, the company started a development and production department for drama in television and films, lead by Jean-Marc Fröhle. Point Prod has since then become a major player in development, production and co-production of drama in Switzerland, in partnership with Swiss and European broadcasters. PILAR ANGUITA-MACKAY – SCREENWRITER, SWITZERLAND Pilar Anguita-MacKay has a Master’s in screenwriting from the University of Southern California (2001). As a screenwriter, she has won awards both in Europe and the United-States: in 2000, the Jack Nicholson Award for the script of A Rose for Maria; in 2007, best screenplay for La Mémoire des Autres, at the 3rd International Film Festival in Funchal. -

3 9 Th G Ö Te Bo Rg F Ilm F E Stiv Al J An

39th Göteborg Film Festival goteborgfilmfestival.se 2016 Jan 29 – Feb 8 2016 #gbgfilmfestival TV Drama Vision Wednesday, February 3 13.00-17.30 Seminar at Biopalatset 18.30-22.00 Dinner cocktail party at Scandic Rubinen, 2nd floor Thursday, February 4 9.00-13.30 Seminar at Biopalatset Venues Biopalatset, Kungstorget 2 Scandic Rubinen, Kungsportsavenyn 24 Price information SEK 1400 with a Network, Industry or Nordic Film Market accreditation SEK 2100 without accreditation This includes dinner at Scandic Rubinen The seminar is held in English. Wi-fi at Biopalatset User: NFM Password: NFM2016 Thank you Katrina Wood and Maya Vuckovic (MediaXChange), Liselott Forsman (YLE), Stefan Baron (Nice Drama), Christian Wikander and Zoula Pitsiava (SVT), Helene Granqvist (WIFT), Josefine Tengblad (TV4), Mikael Newihl (MTG), Ivar Køhn (NRK), Christopher Haug (TV2 Norway), Piv Bernth (DR), Katrine Vogel- sang (TV2 Denmark), Nadja Radojevic (Erich Pommer Institute), Ulrika Nisell (Creative Europe Media Desk Sweden), Lisa Rosengren (Film & TV Producers), Roope Lehtinen (Moskito), Charlotta Denward, Anna Croneman and Anna Anthony (Avanti), Piodor Gustafsson (Spark TV) and Per Janérus (Harmonica Films). TV Drama Vision is supported by Nordisk Film & TV Fond, Västra Götalandsre- gionen, Film Väst and Creative Europe Desk Sweden and presented in collab- oration with MediaXchange. Göteborg Film Festival Office Olof Palmes Plats 1 413 04 Göteborg Phone: +46 (0) 31 339 30 00 Head of Industry and Nordic Film Market Cia Edström Artisic Director [email protected] Jonas Holmberg [email protected] Editors Andrea Reuter and Cia Edström CEO Staffan Settergren Layout [email protected] Klara Andreasson 2 Welcome to TV Drama Vision 2016! The Art of Storytelling In a fast paced and highly personal lecture, Tatjana Andersson, where she is joined by screenwriter Mikko Pöllä, Moskito, and script editor at SVT, kicks off the main theme of this year´s producer Riina Hyytiä, Dionysos Film. -

Cold War Nostalgia for Transnational Audiences

Central European History 54 (2021), 352–360. © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of Central European History Society of the American Historical Association doi:10.1017/S0008938921000480 REVIEW ESSAY The Deutschland Series: Cold War Nostalgia for Transnational Audiences Heather Gumbert OW do you explain the Cold War to a generation who did not live through it? For Jörg and Anna Winger, co-creators and showrunners of the Deutschland series, you Hbring it to life on television. Part pop culture reference, part spy thriller, and part existential crisis, the Wingers’ Cold War is a fun, fast-paced story, “sunny and slick and full of twenty-something eye candy.”1 A coproduction of Germany’s UFA Fiction and Sundance TV in the United States, the show premiered at the 2015 Berlinale before appear- ing on American and German television screens later that year. Especially popular in the United Kingdom, it sold widely on the transnational market. It has been touted as a game-changer for the German television industry for breaking new ground for the German television industry abroad and expanding the possibilities of dramatic storytelling in Germany, and is credited with unleashing a new wave of German (historical) dramas including Babylon Berlin, Dark, and a new production of Das Boot.2 History buffs and—still—historians often seek historical truths in fictional narratives of the past. But historical film and television always tell us more about the moment in which they were created than the periods in which they are set. That is, because television narratives speak to other media narratives, similar to how historians speak to one another through his- toriography. -

When German Series Go Global

volume 9 issue 17/2020 WHEN GERMAN SERIES GO GLOBAL INDUSTRY DISCOURSE ON THE PERIOD DRAMA DEUTSCHLAND AND ITS TRANSNATIONAL CIRCULATION Florian Krauß University Siegen [email protected] Abstract: The article takes a closer look at the current industry discourse on the transnational circulation of German series. At its centre is a case study of the 1980s period drama Deutschland (2015-2020), based on interviews with key executives and creatives. What is it that makes such ready-made TV fiction go transnational, according to the involved practitioners and in this specific case? Textual factors in particular are examined, such as the thematic and aesthetic extension of the historical-political ‘event’ miniseries through Deutschland. Furthermore, the article explores factors in respect to production, including screenwriting and financing, in the context of the dynamic TV landscape in Germany and Europe. Keywords: German television, television series, television production, global television, television scriptwriting, European TV series, period drama, German TV fiction 1 Intr oduction ‘Showrunners and Antiheroes – What Does the German Series Need for International Success?’1 was the title of an industry panel held adjacent to the 2015 Berlin International Film Festival, or Berlinale, at which the first season of the espionage coming-of-age drama Deutschland (2015-2020) premiered. Also during the festival, its sale to the US – a market particularly valued in a Western, transnational context – was announced. The unofficial Berlinale event, where industry attendees applauded this news, and the following media coverage on the US export of Deutschland 83,2 are just a few examples of the recent, ongoing discourse on the transnational circulation of German TV drama. -

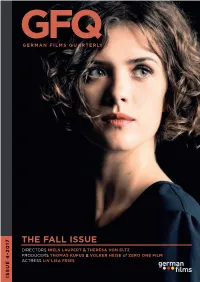

The Fall Issue 1

GFQ4_Druckvorlage_Final.qxp_Layout 1 13.10.17 09:26 Seite 1 GFQ GER MA N F I L M S Q UA R T E RLY 7 THE FALL ISSUE 1 0 DIRECTORS NIELS LAUPERT & THERESA VON ELTZ 2 - PRODUCERS THOMAS KUFUS & VOLKER HEISE of ZERO ONE FILM 4 ACTRESS LIV LISA FRIES E U S S I GFQ4_Druckvorlage_Final.qxp_Layout 1 13.10.17 09:27 Seite 2 CONTENTS GFQ 4-2017 19 21 22 23 25 26 27 28 28 29 30 32 2 GFQ4_Druckvorlage_Final.qxp_Layout 1 13.10.17 09:27 Seite 3 GFQ 4-2017 CONTENTS IN T H I S ISSUE PORTRAITS NEW SHORTS A FRESH PERSPECTIVE FIND FIX FINISH A portrait of director Niels Laupert ................................................. 4 Mila Zhluktenko, Sylvain Cruiziat ................................................... 30 AN EMPATHETIC STORYTELLER GALAMSEY – FÜR EINE HANDVOLL GOLD A portrait of director Theresa von Eltz ............................................. 6 GALAMSEY Johannes Preuss .......................................................... 30 MAKING A MARK LAB/P – POETRY IN MOTION 2 A portrait of the production company zero one film ....................... 8 various directors ............................................................................. 31 BRAINS, BEAUTY & BABYLON BERLIN DAS SATANISCHE DICKICHT – DREI A portrait of actress Liv Lisa Fries ................................................. 10 THE SATANIC THICKET – THREE Willy Hans ............................... 31 WATU WOTE – ALL OF US Katja Benrath .................................................................................. 32 NEWS & NOTES ...............................................................................