ANZUS and the Early Cold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Symphony Hall, Boston Huntington and Massachusetts Avenues

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Branch Exchange Telephones, Ticket and Administration Offices, Back Bay 1492 m INC. PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor FORTY-SECOND SEASON, 1922-1923 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE * NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY BOSTON 8YMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President GALEN L. STONE Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer ALFRED L. AIKEN ARTHUR LYMAN FREDERICK P. CABOT HENRY B. SAWYER ERNEST B. DANE GALEN L. STONE M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE BENTLEY W. WARREN JOHN ELLERTON LODGE E. SOHIER WELCH W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager 205 "CHE INSTRUMENT OF THE IMMORTALS QOMETIMES people who want a Steinway think it economi- cal to buy a cheaper piano in the beginning and wait for a Steinway. Usually this is because they do not realize with what ease Franz Liszt at his Steinway and convenience a Steinway can be bought. This is evidenced by the great number of people who come to exchange some other piano in partial payment for a Steinway, and say: "If I had only known about your terms I would have had a Steinway long ago!" You may purchase a new Steinway piano with a cash deposit of 10%, and the bal- ance will be extended over a period of two years. Prices: $875 and up. Convenient terms. Used pianos taken in exchange. 5' HI N VV A' Y & S'l ) NS STEil N VV K Y S IALL ; 109 EAST 14th STREET NEW YORK Subway Express Stations at the Door REPRESENTED BY THE FOREMOST DEALERS EVERYWHERE 206 lostosa Symplhoinr Foity-second Season, 1922-1923 PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor \k Violins. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

The Evolution of the Franco-American Novel of New England (1875-2004)

BORDER SPACES AND LA SURVIVANCE: THE EVOLUTION OF THE FRANCO-AMERICAN NOVEL OF NEW ENGLAND (1875-2004) By CYNTHIA C. LEES A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 By Cynthia C. Lees ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the members of my supervisory committee, five professors who have contributed unfailingly helpful suggestions during the writing process. I consider myself fortunate to have had the expert guidance of professors Hélène Blondeau, William Calin, David Leverenz, and Jane Moss. Most of all, I am grateful to Dr. Carol J. Murphy, chair of the committee, for her concise editing, insightful comments, and encouragement throughout the project. Also, I wish to recognize the invaluable contributions of Robert Perreault, author, historian, and Franco- American, a scholar who lives his heritage proudly. I am especially indebted to my husband Daniel for his patience and kindness during the past year. His belief in me never wavered. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................ iii LIST OF FIGURES .................................................... vii ABSTRACT.......................................................... viii CHAPTER 1 SITING THE FRANCO-AMERICAN NOVEL . 1 1.1 Brief Overview of the Franco-American Novel of New England . 1 1.2 The Franco-American Novel and the Ideology of La Survivance ..........7 1.3 Framing the Ideology of La Survivance: Theoretical Approaches to Space and Place ....................................................13 1.4 Coming to Terms with Space and Place . 15 1.4.1 The Franco-American Novel and the Notion of Place . -

May, 1952 TABLE of CONTENTS

111 AJ( 1 ~ toa TlE PIANO STYI2 OF AAURICE RAVEL THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Jack Lundy Roberts, B. I, Fort Worth, Texas May, 1952 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OFLLUSTRTIONS. Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF PIANO STYLE ... II. RAVEL'S MUSICAL STYLE .. # . , 7 Melody Harmony Rhythm III INFLUENCES ON RAVEL'S EIANO WORKS . 67 APPENDIX . .* . *. * .83 BTBLIO'RAWp . * *.. * . *85 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Jeux d'Eau, mm. 1-3 . .0 15 2. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), mm. la-3 .r . -* - -* . 16 3. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), 3 a. « . a. 17 4. Ondine (Gaspard de a Nuit), m. 1 . .... 18 5. Ondine (Gaspard de la Nuit), m. 90 . 19 6. Sonatine, first movement, nm. 1-3 . 21 7. Sonatine, second movement, 22: 8. Sonatine, third movement, m m . 3 7 -3 8 . ,- . 23 9. Sainte, umi. 23-25 . * * . .. 25 10. Concerto in G, second movement, 25 11. _Asi~e (Shehdrazade ), mm. 6-7 ... 26 12. Menuet (Le Tombeau de Coupe rin), 27 13. Asie (Sh6hlrazade), mm. 18-22 . .. 28 14. Alborada del Gracioso (Miroirs), mm. 43%. * . 8 28 15. Concerto for the Left Hand, mii 2T-b3 . *. 7-. * * * .* . ., . 29 16. Nahandove (Chansons Madecasses), 1.Snat ,-5 . * . .o .t * * * . 30 17. Sonat ine, first movement, mm. 1-3 . 31 iv Figure Page 18. Laideronnette, Imperatrice des l~~e),i.......... Pagodtes (jMa TV . 31 19. Saint, mm. 4-6 « . , . ,. 32 20. Ondine (caspard de la Nuit), in. 67 .. .4 33 21. -

Flyer Reju Nov-10

97 rue Henri Barbusse 92110 CLICHY FRANCE [email protected] www.rejuvenationrecords.com Voici une petite liste de distrib sans prétention juste pour faire plaisir à tes oreilles, on espère que tu trouveras des choses intéressantes… Notre but n'est pas de faire du profit, mais juste de rentrer dans nos frais. Les disques sont neufs (ou alors c'est précisé), et nous garantissons tout ce que nous vendons. READ THIS BEFORE ANY ORDER ! 1 - Because of our very limited stocks, please send an e-mail to Agnès before any order : agnes(at)rejuvenationrecords.com 2 - All Prices are in EURO. 3 - Shipping is not included, notify us where you live and we will give it to you. 4 - You can pay with well hidden cash (in EURO, please, and at your own risk). 5 - You can pay by paypal to rejuvenation(at)wanadoo.fr. Please add 5% for paypal fees. 6 - You can pay by IMO, just ask us ! 7 - If payment is not received within two weeks of e-mailing us to reserve an order, the order is cancelled. 8 - Now if you're agree with previous lines, we can being very good friends. To have an idea of what can be the shipping costs look at the board below. Thank you ! T'es super nul en anglais (pire que nous ?), ok c'est pas grave : A LIRE AVANT TOUTE COMMANDE ! 1 - En raison de nos quantités super limitées merci de contacter Agnès avant toute commande : agnes(at)rejuvenationrecords.com 2 - Tous les prix sont en EURO. 3 - Le port n'est pas compris, donc dis nous où tu habites et on te donnera le port. -

The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater By

Directed Culture: The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater By Howard Douglas Allen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Victoria E. Bonnell, Chair Professor Ann Swidler Professor Yuri Slezkine Fall 2013 Abstract Directed Culture: The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater by Howard Douglas Allen Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Victoria E. Bonnell, Chair The theater played an essential role in the making of the Soviet system. Its sociological interest not only lies in how it reflected contemporary society and politics: the theater was an integral part of society and politics. As a preeminent institution in the social and cultural life of Moscow, the theater was central to transforming public consciousness from the time of 1905 Revolution. The analysis of a selected set of theatrical premieres from the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 to the end of Cultural Revolution in 1932 examines the values, beliefs, and attitudes that defined Soviet culture and the revolutionary ethos. The stage contributed to creating, reproducing, and transforming the institutions of Soviet power by bearing on contemporary experience. The power of the dramatic theater issued from artistic conventions, the emotional impact of theatrical productions, and the extensive intertextuality between theatrical performances, the press, propaganda, politics, and social life. Reception studies of the theatrical premieres address the complex issue of the spectator’s experience of meaning—and his role in the construction of meaning. -

AAKASH PATEL Contents

History AAKASH PATEL Contents Preface. 1 1. Dawn of Civilization. 2 Mesopotamia . 2 Ancient Egypt . 3 Indus River Valley . 5 2. Ancient Europe . 6 Persian Wars . 6 Greek City-States. 8 Rome: From Romulus to Constantine . 9 3. Asian Dynasties. 23 Ancient India. 23 Chinese Dynasties . 24 Early Korea . 27 4. The Sundering of Europe . 29 The Fall of Rome. 29 Building a Holy Roman Empire . 31 Islamic Caliphates . 33 5. Medieval Times . 35 England: A New Monarchy . 35 France: The Capetians. 42 Germany: Holy Roman Empire. 44 Scandinavia: Kalmar Union. 45 Crusades . 46 Khans & Conquerors . 50 6. African Empires . 53 West Africa . 53 South Africa. 54 7. Renaissance & Reformation. 56 Italian Renaissance . 56 Tudor England . 58 Reformation. 61 Habsburg Empires . 63 French Wars of Religion. 65 Age of Discovery. 66 8. Early Modern Asia . 70 Tsars of Russia . 70 Japan: Rise of the Shogun. 72 Dynastic Korea . 73 Mughals of India. 73 Ottomans of Turkey. 74 9. European Monarchy . 76 Thirty Years' War . 76 Stuart England and the Protectorate . 78 France: Louis, Louis, and Louis . 81 10. Colonies of the New World . 84 Pilgrims and Plymouth . 84 Thirteen American Colonies . 85 Golden Age of Piracy . 88 11. Expansionism in Europe. 89 Ascension of the Romanovs. 89 Rise of Prussia . 91 Seven Years' War . 92 Enlightenment . 93 Hanoverian Succession. 94 12. American Independence . 96 Colonies in the 18th Century . .. -

{Download PDF} Bakunin: Statism and Anarchy Kindle

BAKUNIN: STATISM AND ANARCHY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mikhail Bakunin,Marshall S. Shatz | 300 pages | 01 Jun 2007 | CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780521369732 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom Bakunin: Statism and Anarchy PDF Book This was the first time i read anything by Bakunin which is slightly embarrassing considering his place in history. The Marxists sense this! Preview — Statism and Anarchy by Mikhail Bakunin. But this is not all. Download as PDF Printable version. A beautiful liberation, indeed! A fine idea, that the rule of labour involves the subjugation of land labour! The first of these traits is the conviction, held by all the people, that the land rightfully belongs to them. History they don't teach you in school! They then arrive unavoidably at the conclusion that because thought, theory, and science, at least in our times, are in the possession of very few, these few ought to be the leaders of social life, not only the initiators, but also the leaders of all popular movements. This is the reason brigandage is an important historical phenomenon in Russia; the first rebels, the first revolutionists in Russia, Pugachev and Stenka Razin, were brigands For this it must exercise massive military power. In this sense the propaganda of the International, energetically and widely diffused during the last two years, has been of great value. Jun 29, Jurnalis Palsu rated it liked it. Available to everyone will be a general scientific education, especially the learning of the scientific method, the habit of correct thinking, the ability to generalize from facts and make more or less correct deductions. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 49,1929-1930

SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY Thursday Evening, January 16, at 8.00 ^\WHilJ/iw a? % turn J; "V / BOSTON SYAPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. FORTY-NINTH SEASON 1929-1930 PRSGRHftttE mm^ 4 g J£ =V:^ The PLAZA, New York Fred Sterry John D. Owen President Manager , m^%M^\^\gjA The Savoy-Plaza T/^Copley-Plaza Henry A. Rost New y^ Arthur L. Race Boston President Managing Director Jlotels of ^Distinction Unrivalled as to location. Distin- hed throughout the World for their Appointments and service. =y* SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY FORTY-NINTH SEASON 1929-1930 INC. Dr. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor SEASON 1929-1930 THURSDAY EVENING, JANUARY 16, at 8.00 o'clock WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1930, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President BENTLEY W. WARREN Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer FREDERICK P. CABOT FREDERICK E. LOWELL ERNEST B. DANE ARTHUR LYMAN N. PENROSE HALLOWELL EDWARD M. PICKMAN M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE HENRY B. SAWYER JOHN ELLERTON LODGE BENTLEY W. WARREN W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager There is a STEINWAY priee and model for your home No matter where you live — on a country estate or in a city apartment —there is a Steinway exactly suited to your needs. This great piano is avail- able in five grand sizes, and one upright model, together with many special styles in period designs. But A nrif Slfinuny Uptight *% f% ^^ fij there is only one grade of Steinway. pitnnt tan hi- bought for Mw w *w 1 upw- • Every Steinway, (.it\\»s pbu of every size, com- 91475 "l"tan importation IO% inliinrr in mands that depth and brilliance of down I no \rart tone which is recognized as the pecu- \n> Steinway piano may be pur- liar property - of the Steinway, the chased with .1 < ; 1 1 1 deposit of I' 1 '' . -

Russia's Hostile Measures: Combating Russian Gray Zone

C O R P O R A T I O N BEN CONNABLE, STEPHANIE YOUNG, STEPHANIE PEZARD, ANDREW RADIN, RAPHAEL S. COHEN, KATYA MIGACHEVA, JAMES SLADDEN Russia’s Hostile Measures Combating Russian Gray Zone Aggression Against NATO in the Contact, Blunt, and Surge Layers of Competition For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2539 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0199-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image design: Rick Penn-Kraus Map illustration: Harvepino/Getty Images/iStockphoto Abstract spiral: Serdarbayraktar/Getty Images/iStockphoto Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Russia challenges the security and stability of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and many of its member states. -

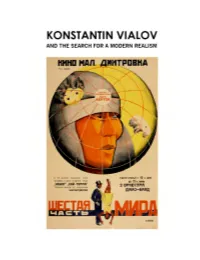

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.