'God Is in the Details': Visual Culture of Closeness in the Circle of Cardinal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Nelson Hubert Minnich Born

CURRICULUM VITAE Nelson Hubert Minnich Born: 15 January 1942, Cincinnati, Ohio Addresses: 5713 37th Avenue Program in Church History Hyattsville, Maryland 20782 Catholic University of America Tel. (301) 277-5891 Washington, D.C. 20064 Tel. (202) 319-5702 (office) or 5079 (CHR) Education: 1959-63 Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) -- part time (Humanities) 1963-65 Boston College (Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts) -- AB (Philosophy) 1965-66 Boston College (Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts) -- MA (History) 1968-70 Gregorian University (Roma, Italia) -- STB (Theology) 1970-77 Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts) -- PhD (History) Dissertation: "Episcopal Reform at the Fifth Lateran Council (1512-17)" directed by Myron P. Gilmore Post-Graduate Distinctions: Foundation for Reformation Research: Junior Fellow (1971) for paleographical studies Institute of International Education: Fulbright Grant for Research in Italy (1972-73) full award for dissertation research -- resigned due to impending death in family Harvard University: Tuition plus stipend (1971-72), Staff Tuition Scholarship (1972-73, 1974- 76), Emerton Fellowship (1972-73), Harvard Traveling Fellowship (1973-74) for dissertation research Sixteenth Century Studies Conference: Carl Meyer Prize (1977) National Endowment for the Humanities: Summer Stipend (1978) to work on the "Protestatio" of Alberto Pio Villa I Tatti: The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies: Fellowship for the summer (1979) to study Leo X's concern for doctrine prior to Luther American Academy -

Il Cortile Delle Statue Der Statuenhof Des Belvedere Im Vatikan

Bibliotheca Hertziana (Max-Planck-Inscitut) Deutsches Archaologisches Instirut Rom Musei Vaticani Sonderdruck aus IL CORTILE DELLE STATUE DER STATUENHOF DES BELVEDERE IM VATIKAN Ak:ten des intemationalen Kongresses zu Ehren von Richard Krautheimer Rom, 21.-23. Oktober 1992 herausgegeben von Matthias Winner, Bernard Andreae, Carlo Pietrangeli (t) 1998 VERLAG PHILIPP VON ZABERN · GEGRUNDET 1785 · MAINZ Ex Uno Lapide: The Renaissance Sculptor's Tour de Force IRVING LAVIN To Matthias Winner on his sixry-fifth birthday, with admiracion and friendship. In a paper published some fifteen years ago, in che coo ccxc of a symposium devoted to artiru and old age, I tried to define what J thoughL was an interesting aspect of Lhc new self-consciousness of che anist that arose in Italy in the Renaissance.' ln the largest sense the phe nomenon consisted in the visual anist providing for his own commemoration, in Lhe fonn of a tomb monument or devoLionaJ image associated with his EinaJ resring place. Although many anists' tombs and commemora tions arc known from antiquity, and some from che middle ages, anises of the Renaissance made such self commemorations on an unprecedented scale and with unprecedented consistency, producing grand and noble works at a time of life when one might have thought that their creative energies were exhausted, or chat they mighL have rested on their laurels. In particular, some of the most powerful works of Italian Renaissance sculp ture were created under these circumstances: the Floren tine Pict.a of Michelangelo, which be intended for his tomb in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (fig. -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

Francisco De Holanda (Ca.1518-1584) Arte Eteoria No Renascimento Europeu

Congresso Internacional Francisco de Holanda (ca.1518-1584) Arte eTeoria no Renascimento Europeu Centro de Arte Moderna da Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (Sala Polivalente) 22 e 23 de Novembro de 2018 Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (Anfiteatro) 24 de Novembro de 2018 Presidente do Congresso Sylvie Deswarte-Rosa, CNRS, IHRIM, ENS LYON Vogais Fernando António Baptista Pereira, CIEBA/FBAUL Vitor Serrão, ARTIS/ FLUL Organização FCG -- Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / Comissariado do Ano Europeu do Património BNP – Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal ARTIS – Instituto de História da Arte da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa CIEBA – Centro de Investigação e Estudos em Belas-Artes da Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade de Lisboa 2 Comissão de Honra Isabel Mota, Presidente da Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian Guilherme d’Oliveira Martins (FCG / Comissário do Ano Europeu do Património) Paulo Ferrão, Presidente da FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia António Cruz Serra, Magnífico Reitor da Universidade de Lisboa Natália Correia Guedes, Presidente da Academia Nacional de Belas Artes Artur Anselmo, Presidente da Academia das Ciências de Lisboa Manuela Mendonça, Presidente da Academia Portuguesada História Luís Aires de Barros, Presidente da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa Francisco Vidal Abreu, Presidente da Academia de Marinha Edmundo Martinho, Provedor da Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Lisboa Inês Cordeiro, Directora da Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal Silvestre Lacerda, Director dos Arquivos Nacionais / Torre do Tombo Zélia Parreira, -

Introduction: the Spirituali and Their Goals

NOT BY FAITH ALONE: VITTORIA COLONNA, MICHELANGELO AND REGINALD POLE AND THE EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY ITALY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Christopher Allan Dunn, J.D. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 19, 2014 NOT BY FAITH ALONE: VITTORIA COLONNA, MICHELANGELO AND REGINALD POLE AND THE EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY ITALY Christopher Allan Dunn, J.D. MALS Mentor: Michael Collins, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Beginning in the 1530’s, groups of scholars, poets, artists and Catholic Church prelates came together in Italy in a series of salons and group meetings to try to move themselves and the Church toward a concept of faith that was centered on the individual’s personal relationship to God and grounded in the gospels rather than upon Church tradition. The most prominent of these groups was known as the spirituali, or spiritual ones, and it included among its members some of the most renowned and celebrated people of the age. And yet, despite the fame, standing and unrivaled access to power of its members, the group failed utterly to achieve any of its goals. By 1560 all of the spirituali were either dead, in exile, or imprisoned by the Roman Inquisition, and their ideas had been completely repudiated by the Church. The question arises: how could such a “conspiracy of geniuses” have failed so abjectly? To answer the question, this paper examines the careers of three of the spirituali’s most prominent members, Vittoria Colonna, Michelangelo and Reginald Pole. -

Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses School of Theology and Seminary 3-13-2018 Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs Stephanie Falkowski College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Falkowski, Stephanie, "Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs" (2018). School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses. 1916. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers/1916 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Theology and Seminary at DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOT QUITE CALVINIST: CYRIL LUCARIS A RECONSIDERATION OF HIS LIFE AND BELIEFS by Stephanie Falkowski 814 N. 11 Street Virginia, Minnesota A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Seminary of Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Theology. SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND SEMINARY Saint John’s University Collegeville, Minnesota March 13, 2018 This thesis was written under the direction of ________________________________________ Dr. Shawn Colberg Director _________________________________________ Dr. Charles Bobertz Second Reader Stephanie Falkowski has successfully demonstrated the use of Greek and Latin in this thesis. -

Negotiating Religious Change Final Version.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Le Baigue, Anne Catherine (2019) Negotiating Religious Change: The Later Reformation in East Kent Parishes 1559-1625. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/76084/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Negotiating Religious Change:the Later Reformation in East Kent Parishes 1559-1625 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies University of Kent April 2019 Word Count: 97,200 Anne Catherine Le Baigue Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements...…………………………………………………………….……………. 3 Notes …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Maps ……..……….……………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Chapter 1: Introduction to the diocese with a focus on patronage …….. 34 Chapter 2: The city of Canterbury ……………………………………………………… 67 Chapter 3: The influence of the cathedral …………………………………………. -

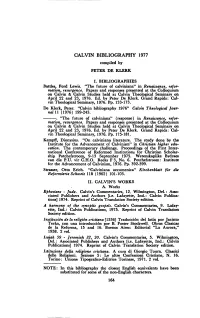

1977 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1977 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Battles, Ford Lewis. "The future of calviniana" in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 133-173. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1976" Calvin Theological Jour- nal U (1976) 199-243. -. "The future of calviniana" (response) in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 175-181. Kempff, Dionysius. "On calviniana literature. The study done by the Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism" in Christian higher edu cation. The contemporary challenge. Proceedings of the First Inter national Conference of Reformed Institutions for Christian Scholar ship Potchefstroom, 9-13 September 1975. Wetenskaplike Bydraes van die P.U. vir C.H.O. Reeks F 3, No. 6. Potchefstroom: Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism, 1976. Pp. 392-399. Strasser, Otto Erich. "Calviniana œcumenica" Kirchenblatt für die Reformierte Schweiz 118 (1962) 101-103. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works Ephesians - Jude. Calvin's Commentaries, 12. Wilmington, Del.: Asso ciated Publishers and Authors [i.e. Lafayette, Ind.: Calvin Publica tions] 1974. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. A harmony of the synoptic gospels. Calvin's Commentaries, 9. Lafay ette, Ind.: Calvin Publications, 1975. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. Institución de la religion cristiana fi536] Traducción del latín por Jacinto Terán, con una introducción por Β. -

Philip Melanchthon's Influence on the English Theological

PHILIP MELANCHTHON’S INFLUENCE ON ENGLISH THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT DURING THE EARLY ENGLISH REFORMATION By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö A dissertation submitted In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology August 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö To the memory of my beloved husband, Tauno Pyykkö ii Abstract Philip Melanchthon’s Influence on English Theological Thought during the Early English Reformation By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö This study addresses the theological contribution to the English Reformation of Martin Luther’s friend and associate, Philip Melanchthon. The research conveys Melanchthon’s mediating influence in disputes between Reformation churches, in particular between the German churches and King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1539. The political background to those events is presented in detail, so that Melanchthon’s place in this history can be better understood. This is not a study of Melanchthon’s overall theology. In this work, I have shown how the Saxons and the conservative and reform-minded English considered matters of conscience and adiaphora. I explore the German and English unification discussions throughout the negotiations delineated in this dissertation, and what they respectively believed about the Church’s authority over these matters during a tumultuous time in European history. The main focus of this work is adiaphora, or those human traditions and rites that are not necessary to salvation, as noted in Melanchthon’s Confessio Augustana of 1530, which was translated into English during the Anglo-Lutheran negotiations in 1536. Melanchthon concluded that only rituals divided the Roman Church and the Protestants. -

Humanism, Hebraism and Scriptural Hermeneutics

CHAPTER SEVEN HUMANISM, HEBRAISM AND SCRIPTURAL HERMENEUTICS Max Engammare Vermigli was as powerful a preacher as he was a scholar.1 In 1542 he fl ed Italy and Lucca where he had served as Prior of the Augustinian Canons of San Frediano, and in the early autumn of that year proceeded to Strasbourg, aft er an initial sojourn in Zurich. Aft er just one month, Bucer invited Vermigli to replace Wolfgang Capito, who had recently died from the plague. Clearly, Bucer thought Vermigli knew suffi cient Hebrew to be able to lecture on the Old Testament. We know he had previously spent time learning Hebrew from a Jewish physician named Isaac in Bologna at the beginning of the 1530s.2 Vermigli studied in the university in both Bologna and Padua for ten years in order to become a teacher. Emidio Campi, Alessandro Pastore and Marcantonio Flaminio are all persuaded that Vermigli is an exemplary product of the Hebraist culture in Renaissance Italy.3 It is my goal to investigate this question by making three further inquires: fi rst, the state of learning Hebrew in Italy at the beginning of the sixteenth century; secondly, the notably high level of interest in studying the Psalms; and fi nally, as I have been fortunate enough to have had the opportunity over the period of almost two decades to inspect Vermigli’s annotations on his own copies of the Rabbinic Bibles (now housed in the library at Geneva), I shall conclude with some remarks on Vermigli’s reading and use of the commentaries of the medieval rabbis. -

Portugal-Venice: Historical Relations — 27 —

Portugal-Venice: Historical Relations — 27 — { trafaria praia } portugal-venice: historical relations Francisco Bethencourt portugal’s relations with italy became formalized in the middle ages, thanks to increas- ing maritime trade between the mediterranean and the north atlantic. throughout this period lisbon functioned as a stopping-off point due to its position on the western coast of the iberian peninsula. between the 12th and the 15th centuries, venetians and genovese controlled several different territories and trading posts throughout the mediterra- nean, with their activity stretching as far east as the black sea (at least up until the conquest of constantinople by the ottomans in 1453). the asian luxury trade was one basis of their wealth. The economic importance of Portugal lay fundamentally in the export of salt. Northern France, Flanders, and England had access to the cereals growing in the north of Europe, which were much coveted by southern Europe; at the same time they were developing metallurgy and woolen textiles. In the 16th century, the population of Flanders was 40 percent city-based, and it was by far the most important city population in Europe. This urban concentration brought with it a specialization of functions and diversified markets. This is why Flanders, followed by England, became specialized in maritime transporta- tion, and then competed with the Venetians and the Genovese. The Portuguese kings used the Italians’ maritime experience to create their military fleet. In 1316, King Denis invited the Genovese mariner Pessagno to be admiral of the fleet, 26 > 33 Francisco Bethencourt — 28 — and the latter brought pilots and sailors with him.