Alternative Finance : What Are the Advantages? Rosette Khalil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

286-294, 2011 Issn 1991-8178

Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 5(7): 286-294, 2011 ISSN 1991-8178 Islamic Financial Culture: Alternative Economic System for Rapid and Sustainable Economic Growth in West African Countries 1Adesina-Uthman Ganiyat Adejoke, 2Ibrahim Olatunde Uthman, 3Taofiq Hassan and 4Shamsher Mohd Ramadili 1Department of Accounting and finance University Putra Malaysia 2Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria 3Department of Accounting and finance University Putra Malaysia 4Graduate School of Management University Putra Malaysia Abstract: West African countries are wealthy countries with abundance of both human and natural resources. Some of its member countries are leading member of the OPEC countries. Surprisingly poverty in West African countries is at an alarming rate. Most of its countries are categorized as underdeveloped countries with highest rate of corruption in the world. It is characterized by very weak economies and very low growth rates. There is prevalence of abject poverty as a result of poor economic managements. They have unstable national currencies which are ever losing value and the masses of their rich country live below the poverty line according to UN classification. This study therefore attempts to unravel ways to employing Islamic financial system as an alternative economic system for rapid and sustainable economic growths in West African countries. The study highlights how Islamic money culture, Islamic financial engineering and other Islamic mechanisms such as the gold payment system, Sukuk, Waqf and Zakah systems can become tools in solving the poverty-ridden conditions of West African countries and their teeming populations. Empirical evidence from Malaysian Sukuk forward rates and inflations revealed that Sukuk forward profit rates have positive effects on real economic growth and have the likelihood to keep inflation at its low. -

Central Banks and Alternative Monetary Alternative Monetary

Central Banks and Alternative Monetary Systems Christopher J. Neely AittViPAssistant Vice Presid idtent, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Annual Educators Conference October 19, 2011 The opinions expressed are my own and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis or the Federal Reserve System. 2 Today’sTopics s Topics Central Banks and Alternative Money Systems o What is Money? o Methods of Monetary Policy o ClBkCentral Banks o Central Banks vs. Commodity Standard 3 What is Money? Money • Money: That which can be exchanged for goods and services. – Functions: • Medium of exchange • Store of value • Unit of measure Why Do We Need Money? • Money solves the mutual coincidence of wants problem. • Greatly reduces transactions costs/shopping time. – My grocer does not want a lecture on economics in exchange for Cheerios. Historical Forms of Money • Commodities: cigarettes, furs, gold, Rai stones (Yap island) • Fiat money: Money whose vvuesoalue is not intrins sc.ic. – Introduced during wartime in the United States • Charac ter is tics of usef ul money – Durable, transportable, divisible, homogenous, easily produced (?) Historical Forms of Money Rai stone Historical Forms of Money • What are the advantages and disadvantages of having a currency that is easily produced? Money Supply • Monetary base: Currency and reserves with the central bank. • Narrow to broad definitions of money – Currency – Demand deposits – Time deposits, CDs, – Shor t-tbdterm bonds • Money and bonds are close to a continuum now – M0, M1, MZM, M2 Money Supply Monetary Base 3000 2500 ars ll 2000 1500 ns of US Dol 1000 Billio 500 Monetary Base (BASE) 0 2/1/1984 2/1/1989 2/1/1994 2/1/1999 2/1/2004 2/1/2009 Money Supply Money supply levels go up and up. -

Implementation of the Gold Dinar: Is It the End of Speculative Measures?

Journal of Economic Cooperation 23 , 3 (2002) 71-84 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GOLD DINAR: IS IT THE END OF SPECULATIVE MEASURES? Dr. Abu Bakar Bin Mohd Yusuf * Nuradli Ridzwan Shah Bin Mohd Dali* Norhayati Mat Husin* The Asian economic crisis, which occurred in 1997, hit the Malaysian and neighbouring countries economies badly. Thailand and South Korea had to turn to IMF rehabilitation funds to ensure that they could revive their economic growth. Suprisingly, Malaysia took an unorthodox way by implementing capital control and pegging the National Ringgit Malaysia at 3.80 to the US dollar. Prime Minister Dato Seri Dr. Mahathir Mohamad blames speculators which contributed heavily to the country's depreciating currency value, thus affecting the overall national economic condition. Even though the SEA countries are feeling the pain from the crisis, their overall economic conditions are moving towards positive reactions after several economic measures have been taken by the affected countries. In the process of economic recovery, Malaysia is searching for an alternative solution to decrease the possibilities of being attacked by speculators. Prime Minister Dato Seri Dr. Mahathir Mohamad first expressed interest in a universal currency that could help unite Muslim countries after attending the OIC summit in Doha, Qatar, in November 2000. This paper will discuss whether the implementation of the universal currency, or the Gold Dinar will stop the speculators’ menace. 1. OVERALL FINANCIAL CRISIS Asia was slashed down by the international financial crisis which spread to other continents. Consequently, efforts to strengthen the architecture of the international financial system, involving finance ministries and central banks from both developed and emerging market economies, have been made. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of March 31, 1965

iA-a 1902 (lTlslon of Central Account* and Reports ipproTed 10/63 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1965 TREASURY DEPARTMENT FISCAL SERVICE BUREAU OF ACCOUNTS TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1965 Prescribed pursuant to section 613 of P.L. 87-195 and section 4a(3) of Procedures Memorandum No. 1, Treasury Circular No. 930, for pur poses of reporting, with certain exceptions, foreign currency bal ances as of March 31, 1965 and transactions for the quarter ending June 30, 1965. RATES OF EXCHANGE COUNTRY F.C. TO &1.00 TYPE OF CURRENCY Aden 7.119 East African shillings Afghanistan 65.00 Afghan afghanis Algeria 4.900 Algerian dinars Argentina 149.5 Argentine pesos Australia .4468 Australian pounds Austria 25.74 Austrian schillings Azores 28.68 Portuguese escudos Bahamas .3574 Bahaman pounds Belgium 49.62 Belgian francs Bermuda .3577 Bermudian pounds Bolivia 11.88 Bolivian pesos Brazil 1825. Brazilian cruzeiros British Honduras 1.430 British Honduran dollars British West Indies 1.714 British West Indian dollars Bulgaria 2.000 Bulgarian leva Burma 4.725 Burmese kyats Cambodia 34.49 Cambodian riels Canada 1.075 Canadian dollars Ceylon 4.758 Ceylonese rupees Chile 3.410 Chilean escudos China (Taiwan) 40.00 New Taiwan dollars Colombia 13.85 Colombian pesos Congo, Republic of the 150.0 Congolese francs Costa Rica 6.620 Costa Rican colones Cyprus .3568 Cyprus pounds Czechoslovakia 14.35 Czechoslovakian korunas Dahomey 245.0 C.F.A. francs Denmark 6.911 Danish kroner Dominican Republic 1.000 Dominican Republic pesos Ecuador 18.47 Ecuadoran sucres El Salvador 2.500 Salvadoran colones Ethiopia 2.481 Ethiopian dollars Fiji Islands -3935 Fijian pounds Finland 3.203 Finnish new markkas France 4.900 French francs French West Indies 4.899 French francs Page 1 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1965 (Continued) RATE OF EXCHANGE COUNTRY F.C. -

CY19 January a Collection of Bitcoin Commentary from the Brightest

CY19 January A collection of Bitcoin commentary from the brightest minds in the crypto community. Crypto Words CY19 January Contents Goals and Scope ......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Support Crypto Words .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cryptocurrency: The Canary in the Coal Mine.................................................................................................. 4 Tweetstorm: Bitcoin’s 10 Year Anniversary ......................................................................................................... 6 Bitcoin: Two Parts Math, One Part Biology .......................................................................................................... 8 Planting Bitcoin - Season (2/4) .................................................................................................................................... 12 Planting Bitcoin - Gardening (4/4) ............................................................................................................................ 18 Planting Bitcoin — Soil (3/4) .......................................................................................................................................... 25 Planting Bitcoin — Species (1/4) ............................................................................................................................... -

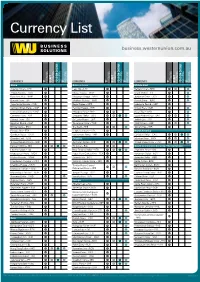

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Must Money Be Limited to Only Gold and Silver?: a Survey of Fiqhi Opinions and Some Implications(1)

JKAU: Islamic Econ., Vol. 19, No. 1, pp: 21-34 (2006 A.D/1427 A.H) Must Money Be Limited to Only Gold and Silver?: A Survey of Fiqhi Opinions and Some Implications(1) MUHAMMAD ASLAM HANEEF and EMAD RAFIQ BARAKAT Associate Professor, Department of Economics International Islamic University Malaysia, and Assistant Professor Department of Islamic Economics and Banking Yarmouk University, Jordan ABSTRACT. This paper attempts to provide a survey into the issue of money in Islam. Specifically, it looks at the views of Muslim scholars (primarily past fiqh scholars), on whether money has to be limited to gold and silver or not and discusses some implications of the findings of this brief survey on present day opinions. In this connection it discusses some general points on gold and silver as money, from a historical and ‘contextual’ perspective, followed by some points that are agreed upon by the majority of scholars. It also compares the views of scholars who take the position that only gold and silver can be used as money and the evidences given to support their stand with the views of those who do not limit money to only gold and silver, together with their evidences. 1. Introduction The discussion of money is certainly as old as the economics discipline itself. Early definitions of the discipline were even focused on money/wealth while most measurements today in economics are based on some money value. In the years since the 1997/98 financial crisis, there has been a renewed interest in and perception popularised by some that the Islamic currency as sanctioned in the shari’ah is gold and silver.(2) The crisis created renewed interest in the discussions and debates on money, the monetary system and even calls for a new international financial architecture. -

Jana Vembunarayanan Lin Yang Stones Used As Money in the Yap Island

Money Jana Vembunarayanan Lin Yang Stones used as money in the Yap Island Rai stones were used as money in Yap island, today a part of the Federated States of Micronesia. The typical Rai stone is carved out of crystalline limestone, and shaped like a disk with a hole in the center. Some of the stones weighed four metric tons, the weight of a typical elephant. Limestones are not native to Yap Island. They had to quarry and canoe from the neighboring island of Palau or Guam, requiring hundreds of people to transport them. These rocks are placed in a prominent location on the Yap island for everyone to see. The owner of the stone could use it as a payment method without moving the stone. All they had to do was to announce to all townsfolk that the stone’s ownership had now moved to the recipient. The very high cost of procuring Rai stones made it a sound form of money. That soundness changed in 1871 when an Irish-American captain by the name of David O’Keefe was shipwrecked on the shores of Yap island and revived by the locals. O’Keefe immediately saw a profit opportunity by selling coconuts found on Yap island to producers of coconut oil. He couldn’t entice the locals to work for him as they were content with their lives. O’Keefe wouldn’t take no for an answer. He sailed to Hong Kong, procured a large boat and explosives. Using modern tools, O’Keefe was able to easily procure huge quantities of Rai stones into Yap island. -

Entrepreneurial Opportunities with Fintechs & Blockchain

Bitcoins, Kryptowährung und Blockchain – was bringt die Zukunft? 23rd October 2018, 2. Forum „Das gute Geld – Investieren mit MehrWert“ Evgeniia Filippova, Senior Scientist @Cryptoeconomics Institute WU Vienna Ledgers Ledgers are used to: - record economic activities; - prove the ownership; - prove the transfer of value of assets (tangible / intangible) among various stakeholders Bank Accounts Land Registries Academic Certificates Every ledger you know is centralized with a ‚trusted‘ Hotel Reservations Medical Records Citizenship Records record-keeper If you had to define Blockchain in 3 words? A distributed ledger Curios case of the Rai Stones 500 AD, Island of Yap (now Micronesia) Yappies had a problem: a strange form of currency (fei stones) Solution: Decentralized Ledger: - Distribution of Fei stone ownership across all Yappies - When a Fei stone was spent, the new transaction was shared across everyone Basic Idea Behind (Bitcoin) Blockchain • Peer-to-peer electronic transactions and interactions • Without financial institution • Cryptographic proof instead of central trust • Put trust in the network instead of in a central institution BLOCKCHAIN So … What is Blockchain? Blockchain is a bundle of distributed ledger technologies that can be programmed to record and track anything of value without involvement of the third trusted party TECHNICAL Back-end database that maintains a distributed ledger, openly BUSINESS Exchange network for moving value between peers LEGAL A transaction validation mechanism, not requiring intermediary assistance What is Blockchain? NETWORK Layer DATABASE Layer STATE Layer time What is Blockchain? NETWORK Layer DATABASE Layer 1. Transaction event A B Digital signature STATE Layer time What is Blockchain? NETWORK Layer DATABASE Layer 1. Transaction event A B Digital signature 2. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

World Bank Document

FILE COPY o RE§UtED 10 R lDOCUMENTO;NTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Not For Public Use Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. P-1612a-YU REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION OF THE PRESIDENT TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized TO REPUBLISKA SKUPNOST ZA CESTE S.R. SLOVENIJE (Republic Community for Roads of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia) ZAJEDNICA PREDUZECA ZA PUTEVE S.R. SRBIJE (Association of Enterprises for Roads of the Socialist Republic of Serbia) and REPUBLISKA SAMOUPRAVNA INTERESNA ZAJEDNICA ZA PUTEVE S.R. CRNE GORE (Self-Managing Republic Interest Community for Roads of-the Socialist Republic of Montenegro) Public Disclosure Authorized WITH THE GUARANTEE OF THE SOCIALIST FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF YUGOSLAVIA FOR A SEVENTH HIGHWAY PROJECT June 25, 1975 Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared for official use only by the Bank Group. It may not be published, quoted or cited without Bank Group authorization. The Bank Group does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the report. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS * Currency Unit Yugoslav Dinar (Din.) US$1 Din. 16.00 Din. 1 us$o.0625 Din. 1,000 US$62.50 Din. 1,000,000 US$62,500.00 * The Yugoslav Dinar has been floating since July 13, 1973. The currency equivalents given above are as of September 30, 197h. The Yugoslav Central Bank established on October 29, 1974 a new intervention rate of US$1.00 equal to Dinars 17.23. Fiscal Year January 1 to December 31 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION OF THE PRESIDENT TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS ON A PROPOSED LOAN TO REPUBLISKA SKUPNOST ZA CESTE S.R. -

The Role of Zakah and Islamic Financial Institution Into Poverty Alleviation and Economics Security No ISBN: 978‑602‑1154‑24‑1

No ISBN: 978‑602‑1154‑24‑1 FACULTY OF ECONOMICS FACULTY OF ISLAMIC AND BUSINESS INSTITUTE OF ISLAMIC BANKING AND FINANCE UNISSULA ‑ SEMARANG UIN SUNAN KALIJAGA ‑ YOGYAKARTA IIUM ‑ MALAYSIA SEMARANG, NOVEMBER 18–19TH 2015 The Role of Zakah and Islamic Financial Institution into Poverty Alleviation and Economics Security No ISBN: 978‑602‑1154‑24‑1 FACULTY OF ECONOMICS FACULTY OF ISLAMIC AND BUSINESS INSTITUTE OF ISLAMIC BANKING AND FINANCE UNISSULA ‑ SEMARANG UIN SUNAN KALIJAGA ‑ YOGYAKARTA IIUM ‑ MALAYSIA i FOREWORD Assalamualaykum.Wr.Wb As a steering committe of 3rd ASEAN INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ISLAMIC FINANCE (AICIF-2015), firstly I would like to say “Thank You Very Much” to all parties for their enermous effort toward the detailed arrangement for hosting this conference. The 3rd AICIF is organized by Faculty of Economics - Sultan Agung Islamic Unisversity (UNISSULA), Faculty of Islamic Economics and Busisness - State Islamic University Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta (UIN Yogyakarta), and Institute of Islamic Banking and Finance – International Islamic University Malaysia. The conference is aimed to discuss “Role of Zakah and Islamic Financial Institution into Poverty Alleviation and Economoics Security”. Islamic financial institution, such as Islamic banking, Islamic unit trust, Islamic insurance, etc.. has growth very fast for last decade. They become important part relating to the efforts improving the quality of life of the society as well as relieving the society from the riba trap. In the context of recent economy, the Islamic financial institutions as economy pillar continues to chalange effort of poverty alleviation. Conference aims to bring together researchers, scientists, and practitioners to share their experiences, new ideas and research results in all aspects of the main conference topics.