An Exploration of the Differences in Characteristics Between Passing and Non- Passing Developmental English Students from a Kansas Community College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let's Take Tomorrow

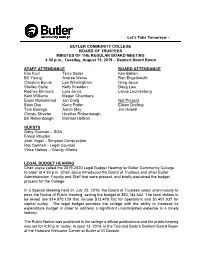

- Let’s Take Tomorrow - BUTLER COMMUNITY COLLEGE BOARD OF TRUSTEES MINUTES OF THE REGULAR BOARD MEETING 4:30 p.m., Tuesday, August 13, 2019 – Dankert Board Room STAFF ATTENDANCE BOARD ATTENDANCE Kim Krull Terry Sader Ken Bohon Bill Young Andrea Weiss Ron Engelbrecht Christina Byrum Lori Winningham Greg Joyce Shelley Stultz Kelly Snedden Doug Law Rodney Dimmick Lora Jarvis Lance Lechtenberg Kent Williams Megan Chambers Esam Mohammad Jon Craig Not Present Brian Dye Kerry Potter Eileen Dreiling Tom Borrego Aaron May Jim Howell Christy Streeter Heather Rinkenbaugh Bill Rinkenbaugh Michael Heffron GUESTS Gaby Guzman – SGA Forest Rhodes Josh Vogel – Simpson Construction Ray Connell – Legal Counsel Vince Haines – Gravity::Works LEGAL BUDGET HEARING Chair Joyce called the 2019-2020 Legal Budget Hearing for Butler Community College to order at 4:30 p.m. Chair Joyce introduced the Board of Trustees and other Butler Administration, Faculty and Staff that were present, and briefly explained the budget process for the College. In a Special Meeting held on July 23, 2019, the Board of Trustees voted unanimously to pass the Notice of Public Hearing, setting the budget at $53,144,642. The local dollars to be levied are $14,970,129 that include $13,478,192 for operations and $1,491,937 for capital outlay. The legal budget provides the college with the ability to increase its expenditure budget in order to address a significant unanticipated expense in a timely fashion. The Public Notice was published in the college’s official publications and the public hearing was set for 4:30 p.m. today, August 13, 2019, in the Ted and Barbra Dankert Board Room of the Hubbard Welcome Center at Butler of El Dorado. -

Board of Regents Meeting Virtually, Via Zoom Protocol Thursday, 5/6/2021 4:00 - 6:00 PM CT

Board of Regents Meeting Virtually, via Zoom Protocol Thursday, 5/6/2021 4:00 - 6:00 PM CT I. Call to Order II. Roll Call Mr. Beck Ms. Buhler Mr. Hoferer Mr. Hulse Mr. Klausman Mr. Padilla Mrs. Parks Mrs. Sourk Mrs. Van Etten III. Approval of Minutes of Past Meeting(s) A. Approval of the Minutes of the March 25, 2021 Meeting March 25, 2021 Washburn University Board of Regents Meeting Minutes - Page 4 IV. Officer Reports A. Chair's Report B. President's Report C. Committee Report(s) 1. Audit Committee - Jennifer Sourk, Chair V. New Business A. Consent Agenda 1. Liquidated Claims Approval - March 2021 - Chris Kuwitzky Liquidated Claims - March 2021 - Page 10 2. WUPRPM Policy Revision - Section E. Benefits - Chris Kuwitzky WUPRPM Policy Revision - Section E. Benefits - Page 11 WUPRPM.Revision. Section E. Benefits.Attachment - Page 12 3. Faculty/Staff Personnel Actions - JuliAnn Mazachek Faculty Staff Personnel Actions - Page 13 B. Action Items 1. Acceptance of FY 2019-2020 Single Audit Report - Chris Kuwitzky Acceptance of Fiscal Year 2020 Audit Report - Page 14 2. Personnel a. Eminentes Universitatis - Chris Kuwitzky Eminentes Universitatis - Page 15 b. Emeriti - JuliAnn Mazachek ________________________________________________________________________________ Master Page # 1 of 63 - Board of Regents Meeting 5/6/2021 Emeriti - Page 18 c. Tenure and Promotion Recommendations - JuliAnn Mazachek Promotion and Tenure - Page 22 3. Expenditures over $50,000 a. Fire Alarm Device Testing - Chris Kuwitzky Fire Alarm Device Testing - Page 23 b. White Concert Hall Stage Lift Repair - Chris Kuwitzky White Concert Hall Stage Lift - Page 24 c. Replacement of Living Learning Center Door Access Control Locks - Chris Kuwitzky Replacement of LLC Suite Door Locks - Page 26 d. -

University Tuition and Fee Proposals

UNIVERSITY TUITION AND FEE PROPOSALS May 19, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 SUMMARY TABLES ................................................................................................................. 1 2 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS ...................................................................................................... 6 3 KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY ............................................................................................. 31 4 WICHITA STATE UNIVERSITY ............................................................................................ 49 5 EMPORIA STATE UNIVERSITY ........................................................................................... 73 6 PITTSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY ....................................................................................... 83 7 FORT HAYS STATE UNIVERSITY ....................................................................................... 94 FY 2022 State University Tuition and Fee Proposal May 2021 The attached documents were prepared by each of the state universities using a uniform format and are organized as outlined below. The narrative of each proposal includes the following sections: Executive Summary. Key facts about the tuition and fee proposal. If the proposal is modified after its initial presentation to the Board, a summary of the changes is added. Section A. Displays the universities’ proposed FY 2022 tuition rates applicable to all students within the designated categories (resident undergraduate, resident graduate, non-resident undergraduate -

Colby Community College Student Success at the Baccalaureate Level

Colby Community College Student Success at the Baccalaureate Level Seth Macon Carter A.A., Allen Community College, 2007 B.A., Emporia State University, 2009 M.S., Pittsburg State University, 2013 Submitted to the Graduate Department and Faculty of the School of Education of Baker University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership Date Defended: December 4, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Seth Macon Carter Abstract There is limited research that focuses on differentiating student success rates at the baccalaureate level (persistence and graduation status) among community college transfer students, and associate degree completing students. Data on student success provided to community colleges for students who transfer to a university do not designate or classify students by associate degree completers and individuals who transferred prior to obtaining an associate degree. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether differences existed in student success (persistence and graduation status) between Colby Community College transfer students who completed an associate degree and Colby Community College transfer students who did not complete an associate degree. For this study, student success was measured in two ways, persistence (persisted, did not persist) and graduation status (graduated, currently enrolled, did not graduate), among the cohort of Colby Community College transfer students who completed an associate degree and Colby Community College transfer students who did not complete an associate degree. The effect of student sex, race, and state of origin of Colby Community College transfer and associate degree completing students was also explored. Sex was defined as the classification of a student as male or female. -

Senate Education Committee January 21, 2021 Blake Flanders, Ph.D. President & CEO, Kansas Board of Regents Good Afternoon Ch

Senate Education Committee January 21, 2021 Blake Flanders, Ph.D. President & CEO, Kansas Board of Regents Good afternoon Chair Baumgardner and Members of the Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to appear today to provide background on the Kansas Board of Regents and our state’s system of higher education. I hope to return to your Committee in coming weeks to share our new strategic plan as well as the recommendations from the Future of Higher Education Council. Today, I will cover the highlights of our System and then plan to take your questions. Board of Regents By state law, the Kansas Board of Regents is balanced with residents of each congressional district and no more than one member from any one county. No more than five of the nine members may be from one political party. Shane Bangerter – Dodge City, 2013 Shelly Kiblinger – Cherryvale, 2019 Ann Brandau-Murguia – Kansas City, 2013 Jon Rolph – Wichita, 2019 Bill Feuerborn (Chair) – Garnett, 2014 Allen Schmidt – Hays, 2018 Cheryl Henderson-Lee – Gardner, 2019 Helen Van Etten – Topeka, 2013 Mark Hutton – Andover, 2018 Goals for Fiscal Year 2021 Helping Kansas Families 1. Improve academic program transfer by creating a systemwide general education (GE) package to align programs under a common framework that guarantees seamless transfer and evaluate the pilot program that increased the number of credit hours eligible for transfer. 2. Review the 60 low-enrollment programs at the six state universities to assess program viability and strengthen the efficiency of degree program inventories. 3. Review university, community college and technical college plans and best practices to improve college-going rates, retention rates, and graduation rates of students from underrepresented populations. -

In PDF Format

Friends University - Systems Portfolio - 6/4/2018 Systems Portfolio Friends University 6/4/2018 Page 1 Friends University - Systems Portfolio - 6/4/2018 1 - Helping Students Learn 1.1 - Common Learning Outcomes Common Learning Outcomes focuses on the knowledge, skills and abilities expected of graduates from all programs. The institution should provide evidence for Core Components 3.B., 3.E. and 4.B. in this section. 1P1: PROCESSES Describe the processes for determining, communicating and ensuring the stated common learning outcomes, and identify who is involved in those processes. This includes, but is not limited to, descriptions of key processes for the following: Aligning common outcomes (institutional or general education goals) to the mission, educational offerings and degree levels of the institution (3.B.1, 3.E.2) Determining common outcomes (3.B.2, 4.B.4) Articulating the purposes, content and level of achievement of the outcomes (3.B.2, 4.B.1) Incorporating into the curriculum opportunities for all students to achieve the outcomes (3.B.3, 3.B.5) Ensuring the outcomes remain relevant and aligned with student, workplace and societal needs (3.B.4) Designing, aligning and delivering cocurricular activities to support learning (3.E.1, 4.B.2) Selecting the tools, methods and instruments used to assess attainment of common learning outcomes (4.B.2) Assessing common learning outcomes (4.B.1, 4.B.2, 4.B.4) 1R1: RESULTS What are the results for determining if students possess the knowledge, skills and abilities that are expected at each degree level? The results presented should be for the processes identified in 1P1. -

Emporia State University Policy Manual.Pdf

UNIVERSITY POLICY MANUAL TABLE OF CONTENTS GUIDING FRAMEWORK University Mission Statement....................................................1 Equal Employment Opportunity, Equal Educational Opportunity and Non-discrimination Policy.................................................1 Affirmation of Values Statement..................................................1 Positioning Statement ..........................................................3 Organizational Chart ...........................................................4 CHAPTER 1. UNCLASSIFIED PERSONNEL 1A. Categories of Unclassified Appointments ............................... 1-1 1A.01 Academic Appointments ................................................ 1-1 1A.0101 Academic Probationary ......................................... 1-1 1A.0102 Academic Tenure .............................................. 1-1 1A.0103 Non-tenure Track Academic ..................................... 1-1 1A.0104 Academic Temporary ........................................... 1-1 1A.02 Administrative Appointments ............................................ 1-2 1A.0201 Administrative Probationary ..................................... 1-2 1A.0202 Administrative Regular ......................................... 1-2 1A.0203 Administrative Temporary ....................................... 1-2 1A.0204 Administrative Athletics ........................................ 1-2 1A.0205 Limited Appointment ........................................... 1-3 1B. Academic Appointment Policies and Procedures ....................... -

TABLE of CONTENTS Programs of Study

PROGRAMS OF STUDY 13 TABLE OF CONTENTS Programs Of Study AGRICULTURE DEGREE PROGRAMS .................................................. 14-20 Manufacturing Engineering Technology Certificate................................. 61 Agribusiness A.S. .................................................................................... 14 Surveying Technology A.A.S and Certificate. ......................................... 62 Agriculture A.S. ...................................................................................... 15 Pre-Engineering A.S. ............................................................................. 63 Livestock Management and Merchandising A.A.S. .................................. 16 Welding Technology A.A.S. ................................................................... 64 Livestock Management and Merchandising Certificate ........................... 17 Welding Technology Certificate .............................................................. 65 Farm and Ranch Management A.A.S. ...................................................... 18 FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION DEGREE PROGRAMS ............. 66-71 Pre-Veterinarian A.S. ............................................................................. 19 Art A.A. and A.S. ................................................................................... 66 Food Science and Safety A.S. .................................................................. 20 Dance A.A. and A.S. .............................................................................. 67 AUTOMOTIVE -

Board of Trustees Regular Meeting Notice for Monday, August 23, 2021

DATE: September 14, 2021 TO: Board of Trustees/News Media/Public FROM: Dr. Dennis C. Rile, President RE: Board of Trustees Regular Meeng Noce The Cowley College Board of Trustees will hold its regular monthly meeng on Monday, September 20, 2021 at 6:00 p.m. in the Short Community Room, inside the Short General Educaon Center, on the Sumner Campus, 2208 Davis‐White Loop, Wellington, KS. The AGENDA for the meeng may be accessed by vising the following link aer 5:00 p.m. on Friday, September 17, 2021 : hps://www.cowley.edu/about/board/agenda/agenda.pdf DCR: tv pc: News Media 1 Agenda Meeting of the Board of Trustees Cowley College September 20, 2021 AGENDA I. Call to Order Gary Wilson, Chair Pg. 4 A. Invocation Dr. Steve Abrams II. Awards and Reports Dr. Dennis C. Rittle, President Pg. 5 A. College Update Dr. Dennis C. Rittle, President B. Reaffirmation of the College Mission Debbie Phelps, Institutional Effectiveness C. Thank you to Cowley College K-State Research and Extension D. Thank you to Cowley College Winfield Local Food Pantry E. Thank you to Cowley College Winfield Chamber of Commerce F. Thank you to Cowley College Aaron Nuss Family G. Thank you to Cowley College Baily H H. Thank you to Cowley College Weston Lowe I. Thank you to Cowley College South Haven High School Class of 2023 J. Thank you to Cowley College Aspen Colquhoun K. Thank you to Cowley College Matik Tatum L. Thank you to the Board of Trustees Pam Smith, Cowley Education Association III. -

Contents • Abbreviations • International Education Codes • Us Education Codes • Canadian Education Codes July 1, 2021

CONTENTS • ABBREVIATIONS • INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES • US EDUCATION CODES • CANADIAN EDUCATION CODES JULY 1, 2021 ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN PROVINCES PROVINCES PROVINCES AL ALABAMA OH OHIO AK ALASKA OK OKLAHOMA CANADA AS AMERICAN SAMOA OR OREGON AB ALBERTA AZ ARIZONA PA PENNSYLVANIA BC BRITISH COLUMBIA AR ARKANSAS PR PUERTO RICO MB MANITOBA CA CALIFORNIA RI RHODE ISLAND NB NEW BRUNSWICK CO COLORADO SC SOUTH CAROLINA NF NEWFOUNDLAND CT CONNECTICUT SD SOUTH DAKOTA NT NORTHWEST TERRITORIES DE DELAWARE TN TENNESSEE NS NOVA SCOTIA DC DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TX TEXAS NU NUNAVUT FL FLORIDA UT UTAH ON ONTARIO GA GEORGIA VT VERMONT PE PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND GU GUAM VI US Virgin Islands QC QUEBEC HI HAWAII VA VIRGINIA SK SASKATCHEWAN ID IDAHO WA WASHINGTON YT YUKON TERRITORY IL ILLINOIS WV WEST VIRGINIA IN INDIANA WI WISCONSIN IA IOWA WY WYOMING KS KANSAS KY KENTUCKY LA LOUISIANA ME MAINE MD MARYLAND MA MASSACHUSETTS MI MICHIGAN MN MINNESOTA MS MISSISSIPPI MO MISSOURI MT MONTANA NE NEBRASKA NV NEVADA NH NEW HAMPSHIRE NJ NEW JERSEY NM NEW MEXICO NY NEW YORK NC NORTH CAROLINA ND NORTH DAKOTA MP NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS JULY 1, 2021 INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES International Education RN/PN International Education RN/PN AFGHANISTAN AF99F00000 CHILE CL99F00000 ALAND ISLANDS AX99F00000 CHINA CN99F00000 ALBANIA AL99F00000 CHRISTMAS ISLAND CX99F00000 ALGERIA DZ99F00000 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS CC99F00000 ANDORRA AD99F00000 COLOMBIA -

AAUP Statement on the Kansas Board of Regents Social Media Policy

AAUP Statement on the Kansas Board of Regents Social Media Policy December 20, 2013 On December 18, the Kansas Board of Regents adopted new rules under which faculty and other employees may be suspended, dismissed or terminated from employment for “improper use of social media.” The policy defines social media as “any facility for online publication and commentary” and covers but is “not limited to blogs, wikis, and social networking sites such as Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Flickr, and YouTube.” This definition could arguably include any message that appears electronically, including email and online periodicals and books. The policy defines “improper use of social media” in extremely broad terms, including communications made “pursuant to ... official duties” that are “contrary to the best interest of the university,” as well as communication that “impairs discipline by superiors or harmony among co- workers, has a detrimental impact on close working relationships for which personal loyalty and confidence are necessary, impedes the performance of the speaker’s official duties, interferes with the regular operation of the university, or otherwise adversely affects the university’s ability to efficiently provide services.” According to media accounts, in voting to adopt the policy the board ignored calls by elected faculty leaders to delay a vote so that there could be more discussion of its ramifications. Although the policy instructs university presidents to “balance the interest of the university in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees against the employee’s right as a citizen to speak on matters of public concern,” it provides no clear guidance as to how such balance might be achieved. -

Let's Take Tomorrow

- Let’s Take Tomorrow - BUTLER COMMUNITY COLLEGE BOARD OF TRUSTEES REGULAR BOARD MEETING 4:30 p.m., Tuesday, November 10, 2020 – Dankert Board Room 3:30 p.m. Board Finance Committee Meeting – President’s Conference Room. 4:30 p.m. Regular Board Meeting – Dankert Board Room, Upper Level of the Hubbard Welcome Center, 901 S. Haverhill Road, El Dorado, Kansas. Executive Session – Not to exceed 30 minutes for consolation with legal counsel regarding real estate to include Dr. Krull, Kent Williams, Lori Winningham, Ray Connell and the Board Budget Work Session – to immediately follow the Regular Board Meeting I. CALL TO ORDER II. APPROVAL OF AGENDA III. EXECUTIVE SESSION ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 IV. RECOGNITIONS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 4 V. PUBLIC COMMENT If you wish to address the Board during Public Comment, please complete this form: https://bit.ly/3b36GXi VI. STANDING REPORTS A. Student Government Association Report – Kiersten Kamholz B. Operational Staff Report – Lisa Bolin C. Professional Employees Report – Terry Sader D. Board Finance Committee Report –Lance Lechtenberg, Shelby Smith E. Foundation Board Report – Forrest Rhodes, Kim Krull F. President’s Report – Kim Krull G. Education Facilities Authority Report –Jim Howell, Doug Law, Kim Krull 1 VII. MONITORING REPORTS A. (I) DIVISION REPORT – Online, High School and Community Learning (H. Rinkenbaugh) ------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 B. (I) SABBATICAL REPORT – Kerry Hale -------------------------------------------13 VIII. BOARD STRATEGIC DISCUSSION – ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES A. COVID-Related Grant Funds (Goering) --------------------------------------------16 IX. BOARD ACTION ITEMS – NONE X. CONSENT AGENDA A. Approval of Minutes of the Regular Board Meeting of October 13, 2020 (Jarvis) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------25 B. Approval of Bills and Warrants for October 2020 (Wilson) -------------------52 C.