THE SYMBOLIC MEANING of COPERNICUS' SEAL The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The False Narrative of Syphilis and Its Origin in Europe

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU HIST 4800 Early America in the Atlantic World (Herndon) HIST 4800 Summer 6-11-2014 Neither “Headache” Nor “Illness:” The False Narrative of Syphilis and its Origin in Europe Michael W. Horton Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/hist4800_atlanticworld Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Repository Citation Horton, Michael W., "Neither “Headache” Nor “Illness:” The False Narrative of Syphilis and its Origin in Europe" (2014). HIST 4800 Early America in the Atlantic World (Herndon). 2. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/hist4800_atlanticworld/2 This Student Project is brought to you for free and open access by the HIST 4800 at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIST 4800 Early America in the Atlantic World (Herndon) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Mike Horton HIST 4800: Research Seminar Dr. Ruth Herndon June 11, 2014 Neither “Headache” Nor “Illness:” The False Narrative of Syphilis and its Origin in Europe. Abstract In this paper I argue that the master narrative of the origin of syphilis in Europe, known as the Columbian Theory does not hold up to historical review since it does not contain enough concrete evidence for we as historians to be comfortable with as the master narrative. To form my argument I use the writings of Girolamo Fracastoro, an Italian physician known for coining the term “syphilis,” as the basis when I review the journal of Christopher Columbus. I review his journal, which chronicles the first voyage to the Americas, to see if there is any connection between the syphilis disease and him or his crew. -

Claudius Ptolemy: Tetrabiblos

CLAUDIUS PTOLEMY: TETRABIBLOS OR THE QUADRIPARTITE MATHEMATICAL TREATISE FOUR BOOKS OF THE INFLUENCE OF THE STARS TRANSLATED FROM THE GREEK PARAPHRASE OF PROCLUS BY J. M. ASHMAND London, Davis and Dickson [1822] This version courtesy of http://www.classicalastrologer.com/ Revised 04-09-2008 Foreword It is fair to say that Claudius Ptolemy made the greatest single contribution to the preservation and transmission of astrological and astronomical knowledge of the Classical and Ancient world. No study of Traditional Astrology can ignore the importance and influence of this encyclopaedic work. It speaks not only of the stars, but of a distinct cosmology that prevailed until the 18th century. It is easy to jeer at someone who thinks the earth is the cosmic centre and refers to it as existing in a sublunary sphere. However, our current knowledge tells us that the universe is infinite. It seems to me that in an infinite universe, any given point must be the centre. Sometimes scientists are not so scientific. The fact is, it still applies to us for our purposes and even the most rational among us do not refer to sunrise as earth set. It practical terms, the Moon does have the most immediate effect on the Earth which is, after all, our point of reference. She turns the tides, influences vegetative growth and the menstrual cycle. What has become known as the Ptolemaic Universe, consisted of concentric circles emanating from Earth to the eighth sphere of the Fixed Stars, also known as the Empyrean. This cosmology is as spiritual as it is physical. -

Kepler's Cosmological Synthesis

Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 39 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J. M. M. H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C. H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 20 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis Astrology, Mechanism and the Soul By Patrick J. Boner LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Kepler’s Supernova, SN 1604, appears as a new star in the foot of Ophiuchus near the letter N. In: Johannes Kepler, De stella nova in pede Serpentarii, Prague: Paul Sessius, 1606, pp. 76–77. Courtesy of the Department of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Milton S. Eisenhower Library, Johns Hopkins University. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Boner, Patrick, author. Kepler’s cosmological synthesis: astrology, mechanism and the soul / by Patrick J. Boner. pages cm. — (History of science and medicine library, ISSN 1872-0684; volume 39; Medieval and early modern science; volume 20) Based on the author’s doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge, 2007. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24608-9 (hardback: alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-24609-6 (e-book) 1. Kepler, Johannes, 1571–1630—Philosophy. 2. Cosmology—History. 3. Astronomy—History. I. Title. II. Series: History of science and medicine library; v. 39. III. Series: History of science and medicine library. Medieval and early modern science; v. 20. QB36.K4.B638 2013 523.1092—dc23 2013013707 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The science of the stars in Danzig from Rheticus to Hevelius / Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7n41x7fd Author Jensen, Derek Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO THE SCIENCE OF THE STARS IN DANZIG FROM RHETICUS TO HEVELIUS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History (Science Studies) by Derek Jensen Committee in charge: Professor Robert S. Westman, Chair Professor Luce Giard Professor John Marino Professor Naomi Oreskes Professor Donald Rutherford 2006 The dissertation of Derek Jensen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii FOR SARA iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page........................................................................................................... iii Dedication ................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ...................................................................................................... v List of Figures .......................................................................................................... -

Syphilis and Theories of Contagion Curtis V

Syphilis and Theories of Contagion Curtis V. Smith, Doctoral Candidate Professor of Biological Sciences Kansas City Kansas Community College Abstract Syphilis provides a useful lens for peering into the history of early modern European medicine. Scholarly arguments about how diseases were transmitted long preceded certain scientific information about the etiology or cause of disease in the late 19th century. Compared to the acute and widely infectious nature of bubonic plague, which ravaged Europe in the mid-15th century, syphilis was characterized by the prolonged chronic suffering of many beginning in the early 16th century. This study reveals the historical anachronisms and the discontinuity of medical science focusing primarily on the role of Girolamo Fracastoro (1478-1553) and others who influenced contagion theory. Examination of contagion theory sheds light on perceptions about disease transmission and provides useful distinctions about descriptive symptoms and pathology. I. Introduction Treponema pallidum is a long and tightly coiled bacteria discovered to be the cause of syphilis by Schaudinn and Hoffman on March 3, 1905. The theory of contagion, or how the disease was transmitted, was vigorously debated in Europe as early as the sixteenth century. Scholarly arguments about how diseases were transmitted long preceded scientific information about the etiology or cause of disease. The intense debate about syphilis was the result of a fearsome epidemic in Europe that raged from 1495-1540. Compared to the Black Death, which had a short and sudden acute impact on large numbers of people one hundred and fifty years earlier, syphilis was characterized by the prolonged chronic suffering of many. -

Sect in Astrology Slides

Day and Night • One of the most fundamental astronomical cycles. • But what does it mean in astrology? • Concept of sect recently recovered from ancient astrology. • Posits a distinction between day and night charts. • Interpretation of basic chart placements altered. • Broad overview of sect in this talk. The Two Teams or Sects • Greek hairesis: a faction, party, school, or religious sect. • The planets are divided into two teams. • Each team is led by a luminary: giver of light. – Day team led by the Sun – Night team led by the Moon Sect as a Foundational Concept • Sect shows up everywhere in ancient astrology: – Domicile assignments – Joys – Exaltations – Triplicity rulers – Lot calculations (e.g. Lot or Part of Fortune) – Master of the Nativity – Some timing techniques • It is not a minor technique or concept. Domiciles Aspects Receive Emit Exaltations Exaltations, Sect, and Aspects Solar hemisphere: spirit, soul, mind Planetary Joys Lunar hemisphere: fortune, body, matter Calculating the Lot of Fortune • The Arabic Parts are geometrical calculations. • The Lot of Fortune is reversed by day and night. • Has to do with sect light, and light/dark analogy. The Master of the Nativity • The overall ruler of the chart. • To find the Master, you must first find the Predominator. • Three candidates: Sun, Moon, or Ascendant. – Strongest luminary preferred. • Domicile lord of predominator becomes Master. • Interesting implications: – Many born during the day characterized by Sun-sign. – Many born at night characterized more by Moon-sign. • See TAP #205 for more on this. Annual Profections and Sect • Profections is an ancient timing technique. • Count one sign per year from the rising sign. -

The Tetrabiblos

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com %s. jArA. 600003887W s ♦ ( CUAEPEAJr TERMST) T »|n 2E SI m -n_ Til / Vf .eras X ,8 ¥ 8JT? 8 i 8 %8 $ 8 »! c? 8 U 8 9 8 17? £ 8 9 7 u ?2 it 7 9 7 1?„ *1 It' 9 7 T?76 ?x U7 *S V? <* 6 9.6 6 5 v76 cf 6 9 6 *8 ?? A$6 0 5 »2 rf 5 U5 ni * a <* 5 \b 6** *l <? 5 U*6* <* 4 M 94 ?* <J 4 U4 9 *j? tic? 4 U4 9 4 9" \ ______ - Of the double Figures . the -first is the Day term.. the secontl.theNioht. * Solar Semicircle.-. A TiJ ^= tx\ / Vf lunar Df 03 1 8 t K « U Hot & Moist. Commanding T S IL S Jl nj i...Hot icDrv. Obeying ^ n\ / vf-=X %...HotSc Dry Moderately Masculine Diurnal. .TH A^/at %... Moist StWarnv. Feminine Nocturnal. B S Trj tit. Vf X y.. Indifferent . long Ascension Q «n«j^5=Tr^/ ~}..- Moist rather Warm.. ifibvl Z».* vy set X T W H I* ? k J . Benetic •-. Fixed tf «a TH. sas 1? <? Malefic. Bicorporeal _H ttj / X 0 y.... Indifferent.. Tropical °3 Vf \l J* iQMasculine. Equinoctial T ^i= ^ ^ Feminine . Fruitful d n\ X y Indifferent . Beholding icof..\ H & <5|/ &Vf I> \%Dj.. Diurnal. Equal Fewer. ...) 7* -rrK]=fi=-x ^J- 4 % } .Nocturnal . The Aspects 8 A D *^n{)'. -

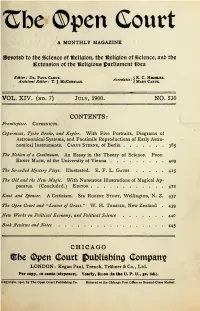

Copernicus, Tycho Brache, and Kepler

^be ©pen Gourt A MONTHLY MAGAZINE S)c\>otc& to tbc Science of "Religfon, tbe IRellgton of Science, an& tbe Bitension ot tbe IReliQious parliament f&ea EcHtor: Dr. Paul Caids. E- C. Hboblu. Astoaaus.j,.^^^t,..S -j Atnttant Editor: T. J. McCoemack. j^^^^^ Cards. VOL. XIV. (no. 7) July, 1900. NO. 530 CONTENTS: Frontispiece. Copernicus. Copernicus, Tycho Brake, and Kepler. With Five Portraits, Diagrams of Astronomical Systems, and Facsimile Reproductions of Early Astro- nomical Instruments. Carus Sterne, of Berlin 385 The Notion of a Continuum. An Essay in the Theory of Science. Prof. Ernst Mach, of the University of Vienna 409 The So-called Mystery Plays. Illustrated. E. F. L. Gauss 415 The Old and the New Magic. With Numerous Illustrations of Magical Ap- paratus. (Concluded.) Editor 422 Kant and Spencer. A Criticism. Sir Robert Stout, Wellington, N. Z. 437 The Open Court and ^'Leaves of Grass.'" W. H. Trimble, New Zealand . 439 New Works on Political Economy, and Political Science 440 Book Eeviews and Notes 445 CHICAGO ®be ©pen Court IpubUsbing Companie LONDON : Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co., Ltd. Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (In the U. P. U., 5s. 6(L). Copyright, 1900, by Tbe Open Court PvbliahiaK Co. Entered at the Chic«Ko Post Oflk;e as Second>Clasa MatUr. ^be ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE 2)cvote& to tbe Science of IReligion, tbe IReUaton of Science, arH> tbe Extension ot tbe IReligious parliament irt)ea EcHtfr: Dr. Ca«us. E. C. Hboblxk. Paul Af*otMi€M.>#,,<,««/^, j j^^^^^ Atnsiant Editor: T. -

Hieronymi Fracastorii: the Italian Scientist Who Described the “French Disease”*

MEMORY 684 s Hieronymi Fracastorii: the Italian scientist who described the “French disease”* Filippo Pesapane1,2 Stefano Marcelli2,3 Gianluca Nazzaro1,2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20154262 Abstract: Girolamo Fracastoro was a true Italian Renaissance man: he excelled in literature, poetry, music, geog- raphy, geology, philosophy, astronomy and, of course, medicine to the point that made Charles-Edward Armory Winslow define him as “a peak unequaled by anyone between Hippocrates and Pasteur”. In 1521 Fracastoro wrote the poem “Syphilis Sive de Morbo Gallico” in which was established the use of the term “syphilis” for this terrible and inexplicably transmitted disease, often referred to as “French disease” by the people of the time and by Fracastoro himself. Keywords: Syphilis; History of Medicine; Dermatology; Infection control; Pathology Hieronymi Fracastorii, or Girolamo Fracastoro, Pope Paolo III, in 1545, named Fracastoro doc- (1483-1553) was one of the most important people at tor of the Council of Trent. In this role Fracastoro it- the center of the intellectual scene of the early six- self was determinant in moving the seat of the council teenth century, not only for the famous poem “Syphils from Trent to Bologna, due to an outbreak of typhus, a sive Morbus Gallicus” (1530), but also for its proposal disease that was first described in his book “De Conta- for an alternative to the Ptolemaic astronomical sys- gione et Contagiosis Morbis”. 2 tem, developed a few years before the Copernican rev- However, it was another disease that made olution, based on the renewal of homocentrism.1 Fracastoro famous: at the beginning of the sixteenth Its importance in the history of medicine is due century an unpublished and incurable epidemic was to its many natural and medical considerations, rep- spreading wildly, affecting an alarming population. -

Kepler's Optical Part of Astronomy (1604)

Kepler’s Optical Part of Astronomy (1604): Introducing the Ecliptic Instrument Giora Hon University of Haifa Yaakov Zik University of Haifa For William H. Donahue The year 2009 marks the 400th anniversary of the publication of one of the most revolutionary scientiªc texts ever written. In this book, appropriately en- titled, Astronomia nova, Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) developed an as- tronomical theory which departs fundamentally from the systems of Ptolemy and Copernicus. One of the great innovations of this theory is its dependence on the science of optics. The declared goal of Kepler in his earlier publication, Paralipomena to Witelo whereby The Optical Part of Astronomy is Treated (Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena, quibus astronomiae pars optica traditvr, 1604), was to solve difªculties and expose illusions astron- omers face when conducting astronomical observations with optical instru- ments. To avoid observational errors that had plagued the antiquated mea- Early versions of this paper were presented in XXV Scientiªc Instruments Commission Sympo- sium, “East and West: The Common European Heritage,” held in Krakow, Poland, 10–14 September, 2006; and in the meeting of the History of Science Society held in Vancouver, No- vember 2–5, 2006. We are indebted to the participants of these meetings for their com- ments. In particular, we thank Wilbur Applebaum for his valuable remarks. We thank Ron Alter of the University of Haifa Library for his help in acquiring material for our re- search. We are grateful to Dov Freiman and Avishi Marson of Elbit Systems, Electro- Optics ELOP, Ltd., for instructive discussions and optical simulations. We thank Ilan Manulis, director of The Harry Kay Observatory at the Technoda, Hadera, Israel, for using the Observatory infrastructure in September 2007. -

Medical History

ANNALS OF MEDICAL HISTORY FRANCIS R'PACKARD'M'D'EDITOR [PHILADELPHIA] PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY PAUL - B - HOEBER 67-69 EAST FIFTY-NINTH STREET * NEW YORK CITY p p f ! mm.. ■ '^ r * T ? ANNALS OF MEDICAL HISTORY V o l u m e i S p r i n g 1917 N u m b e r i A ...... *y" THE SCIENTIFIC POSITION OF GIROLAMO FRACASTORO [1478 ?—1553] WITH ESPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE SOURCE, CHARACTER AND INFLUENCE OF HIS THEORY OF INFECTION By CHARLES AND DOROTHEA SINGER OXFORD, ENGLAND IROLAMO FRAC- has been called the “ academic” period of ASTORO was born the Renaissance and received the most in Verona in 14 7 8 1 complete education available in his day. In and he died in his his youth he attended the University of villa near that city Padua, where he had a number of brilliant in 1553. He came of associates, several of whom exercised con an honorable stock siderable influence upon him. Among them which had produced were Gaspare Contarini (1483-1542) who many distinguished physicians. Of one of later, as cardinal, sought, at the diet of these, Aventino Fracastoro, who was prac Ratisbon, to effect a reconciliation between tising medicine as early as 1325 we read Catholics and Protestants; Giambattista that he was medica clarissimus arte, astra Rhamnusio (1485-1557), the Italian Hak poll novit novitque latencia rerum, utile luyt, who inscribed to Fracastoro his great consilium civibus et dominis.2 Viaggi et Navigationif the fine scholar Andrea Navagero (1483-1529) to whom y I. THE CHARACTER AND WRITINGS OF Teobaldo Manucci dedicated the editio prin- FRACASTOR ceps of Pindar4 and who himself edited for the The subject of our study, Girolamo Aldine press the works of Quintilian, Virgil, Fracastoro, was himself brought up in what Lucretius, Ovid, Terence, Horace and the 1 The date usually given for Fracastor’s birth is in Italia,” Venice, 1915, p. -

Prophecy, Cosmology and the New Age Movement: the Extent and Nature of Contemporary Belief in Astrology

PROPHECY, COSMOLOGY AND THE NEW AGE MOVEMENT: THE EXTENT AND NATURE OF CONTEMPORARY BELIEF IN ASTROLOGY NICHOLAS CAMPION A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Bath Spa University College Study of Religions Department, Bath Spa University College June 2004 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge helpful comments and assistance from Sue Blackmore, Geoffrey Dean, Ronnie Dreyer, Beatrice Duckworth, Kim Farnell, Chris French, Patrice Guinard, Kate Holden, Ken Irving, Suzy Parr and Michelle Pender. I would also like to gratefully thank the Astrological Association of Great Britain (AA), The North West Astrology Conference (NORWAC), the United Astrology Congress (UAC), the International Society for Astrological Research (ISAR) and the National Council for Geocosmic Research (NCGR) for their sponsorship of my research at their conferences. I would also like to thank the organisers and participants of the Norwegian and Yugoslavian astrological conferences in Oslo and Belgrade in 2002. Ill Abstract Most research indicates that almost 100% of British adults know their birth-sign. Astrology is an accepted part of popular culture and is an essential feature of tabloid newspapers and women's magazines, yet is regarded as a rival or, at worst, a threat, by the mainstream churches. Sceptical secular humanists likewise view it as a potential danger to social order. Sociologists of religion routinely classify it as a cult, religion, new religious movement or New Age belief. Yet, once such assumptions have been aired, the subject is rarely investigated further. If, though, astrology is characterised as New Age, an investigation of its nature may shed light on wider questions, such as whether many Christians are right to see New Age as a competitor in the religious market place.