Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8s46xqw No online items Inventory of the United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Liz Phillips University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections 2017 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA 95616-5292 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/archives-and-special-collections/ Inventory of the United States O-016 1 Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections Title: United States Theatre Programs Collection Creator: University of California, Davis. Library Identifier/Call Number: O-016 Physical Description: 38.6 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1870-2019 Abstract: Mostly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Researchers should contact Archives and Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Scope and Contents Collection is mainly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Access Collection is open for research. Processing Information Liz Phillips converted this collection list to EAD. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], United States Theatre Programs Collection, O-016, Archives and Special Collections, UC Davis Library, University of California, Davis. Publication Rights All applicable copyrights for the collection are protected under chapter 17 of the U.S. Copyright Code. Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Regents of the University of California as the owner of the physical items. -

Caryl Churchill's Fourth New Play Imp Announced

PRESS RELEASE Friday 7 June 2019 CARYL CHURCHILL’S FOURTH NEW PLAY IMP ANNOUNCED Following last month’s announcement of new work which included details of three new Caryl Churchill plays, the Royal Court Theatre announces today a fourth play, Imp, just received from the celebrated writer. Glass. Kill. Bluebeard. Imp. will be directed by James Macdonald and will run in the Jerwood Theatre Downstairs Wednesday 18 September 2019 – Saturday 12 October 2019 with press night on Wednesday 25 September 2019, 7pm. Artistic Director of the Royal Court Theatre Vicky Featherstone said; “As Artistic Director of the Royal Court the precious moment when a play by Caryl Churchill arrives fully formed, breaking new ground and utterly surprising us is what this job is all about. I thought the delight I felt when she sent Glass, Kill and Bluebeard would be unsurpassed. Imagine then the joy when two weeks ago the wonderful Imp dropped into my inbox. So now we have four new and extraordinary plays by Caryl in our autumn season. Not three.” Set design by Miriam Buether, costume design by Nicky Gillibrand, lighting design by Jack Knowles and sound design by Christopher Shutt. “I can see her just. Most people can’t see her at all.” A girl made of glass. Gods and murders. A serial killer’s friends. And a secret in a bottle. Four stories by Caryl Churchill. Caryl Churchill’s most recent play Escaped Alone, opened at the Royal Court to critical acclaim and transferred to New York. Many of her plays which first premiered at the Royal Court are now considered modern classics including Top Girls, A Number and Far Away. -

April 1 to October 31 Niagara-On-The-Lake, Ontario

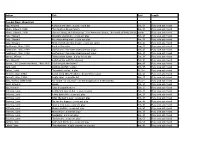

April 1 to October 31 Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario JACKIE MAXWELL Artistic Director The 2010 Shaw Festival Company Festival Theatre AN IDEAL HUSBAND 5 TO BE UPDATED Benedict Campbell David Jansen Marla McLean Ken James Stewart April 9 to October 31 Kawa Ada Lisa Codrington Gabrielle Jones Patrick McManus Richard Stewart Beryl Bain Krista Colosimo Claire Jullien Jim Mezon Steven Sutcliffe THE WOMEN 7 Michael Ball Nicolá Correia- Lorne Kennedy Peter Millard Jacqueline Thair May 12 to October 9 Guy Bannerman Damude Corrine Koslo Ali Momen Wendy Thatcher Neil Barclay Saccha Dennis Al Kozlik Laurie Paton Jay Turvey THE DOCTOR’S DILEMMA 9 Anthony Bekenn Sharry Flett Peter Krantz Gray Powell Mark Uhre June 10 to October 30 Donna Belleville Patrick Galligan Billy Lake Micheal Querin Jonathan Widdifield Kyle Blair Patricia Hamilton Anthony Malarky Ric Reid Robin Evan Willis Court House Theatre Evan Buliung Mary Haney Esther Maloney David Schurmann Kelly Wong THE CHERRY ORCHARD 11 Andrew Bunker Deborah Hay Thom Marriott Goldie Semple Jenny L. Wright April 20 to October 2 Fiona Byrne Patty Jamieson Julie Martell Graeme Somerville Jenny Young JOHN BULL’S OTHER ISLAND 13 June 18 to October 9 AGE OF AROUSAL 15 July 23 to October 10 Royal George Theatre HARVEY 17 April 1 to October 31 MANDATE TO COME ONE TOUCH OF VENUS 19 May 16 to October 10 HALF AN HOUR 21 LOREM IPSUM June 26 to October 9 LUNCHTIME Studio Theatre SERIOUS MONEY 23 July 31 to September 12 Reading Series 24 How to Order Tickets 25 Gift Certificates + Memberships 25 Theatre for all Budgets -

Bigsby, Christopher. "Index." Staging America. London: Methuen Drama, 2020

Bigsby, Christopher. "Index." Staging America. London: Methuen Drama, 2020. 235–239. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:24 UTC. Copyright © Christopher Bigsby 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. I N D E X Abbie’s Irish Rose , 7 Bechdel, Alison, 97 Adjmi, David, 2 Beckett, Samuel, 103, 107, 120, 151 Adventures of the Barrio Grrr!! (Hudes), 79 Beautiful Mind, A , 37 Afghanistan invasion, 135, 177, 178, 180–4, 200 Betrayal (Packer), 164 Against (Shinn), 189, 210–12 Between Riverside and Crazy (Guirgis), 74–6 Akhtar, Ayad, 1, 6 ‘Big Two-Hearted River’ (Hemingway), 136 American Dervish , 10, 13–16, 17 Billington, Michael, 29, 68, 100, 154, 165, 171, 179, Disgraced , 6, 13, 16–20, 55–6 182–3, 188, 212 Invisible Hand, Th e , 6, 13, 20–2 bin Laden, Osama, 21, 22 Junk: Th e Golden Age of Debt , 6, 26–30 Birth of Tragedy, Th e (Nietzsche), 127 early life and family infl uences, 10–11, 15 Blood and Gift s (Rogers), 2, 6, 178–83, 184 War Within, Th e , 11–12 Blue Bonnet State (Norris), 132 Who & the What, Th e , 7–8, 9, 13, 22–6 Bond, Edward, 190 Albee, Edward, 149, 169, 186 Boom Boom Boom Boom (Guirgis), 59 Alexie, Sherman, 106 Bosch, Hieronymus, 103 Als, Hilton, 124, 128 Brantley, Ben, 29, 64, 68, 71, 177, 188, 196, 203, 207, 215 Alsop, Joseph, 47–53 Breasts of Tiresias, Th e , (Apollinaire), 103 -

Títol De La Tesi: Gender, Politics, Subjectivity: Reading Caryl Churchill

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de la Universitat de Barcelona DEPARTAMENT DE FILOLOGIA ANGLESA I ALEMANYA UNIVERSITAT DE BARCELONA Programa de doctorat: Literatura i identitat Bienni 1992-94 per optar al títol de doctor en Filologia Anglesa Títol de la tesi: Gender, Politics, Subjectivity: Reading Caryl Churchill Nom del doctorand: Enric MONFORTE RABASCALL Nom de la directora de la tesi: Pilar ZOZAYA ARIZTIA Data de lectura: 25 de febrer de 2000 Als meus pares, Isabel Rabascall Puig i Enric Monforte Tena, amb afecte. A la memòria de Bryan Allan. CONTENTS AGRAÏMENTS ................................................. v INTRODUCTION ................................................. vii CHAPTER I. FEMINISM AND THEATRE ............................ 1 CHAPTER II. THATCHER'S ENGLAND .............................. 29 CHAPTER III. CARYL CHURCHILL: A WOMAN PLAYWRIGHT ............. 43 CHAPTER IV. ORGASMS AND ORGANISMS: CLOUD NINE AS THE DISRUPTION OF THE SYMBOLIC ORDER ......... 67 CHAPTER V. IRON MAIDENS, DOWNTRODDEN SERFS: TOP GIRLS OR HOW WOMEN BECAME COCA-COLA EXECUTIVES ............................ 137 CHAPTER VI. CRUNCHING ONE'S OWN PRICK: BLUE HEART AND THE POSTSTRUCTURALIST FEMINIST CANNIBALISM OF THE PATRIARCHAL MALE SUBJECT ..... 233 CONCLUSIONS ................................................. 291 APPENDIX ................................................. 307 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................. 323 iii AGRAÏMENTS A la Doctora Pilar Zozaya he d'agrair-li la seva vàlua, tant a nivell personal com professional. He tingut el plaer de comprovar-ho en ambdues vessants. A nivell personal, fruint de la seva simpatia i amabilitat. A nivell professional, com a alumne a les seves classes de teatre anglès, on vaig intentar aprendre part del seu rigor i del seu avançat sistema pedagògic. Com a col.lega a la Universitat de Barcelona he tingut l’oportunitat de continuar aprenent al seu costat. -

I a BRECHTIAN ANALYSIS of CARYL CHURCHILL's MAD FOREST and EDWARD BOND's RED, BLACK and IGNORANT a THESIS SUBMITTED to TH

A BRECHTIAN ANALYSIS OF CARYL CHURCHILL’S MAD FOREST AND EDWARD BOND’S RED, BLACK AND IGNORANT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY AYŞE YÖNKUL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE JANUARY 2013 i Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences _________________________ Prof. Dr. Meliha ALTUNIŞIK Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. _________________________ Prof. Dr. Gölge SEFEROĞLU Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. _________________________ Asst. Prof. Dr. Hülya YILDIZ BAĞÇE Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Meral ÇİLELİ (METU, ELIT) ________________________ Asst. Prof. Dr. Hülya YILDIZ BAĞÇE (METU, ELIT) ________________________ Prof. Dr. Esin TEZER (METU, EDS) ________________________ ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all the material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Ayşe YÖNKUL Signature: iii ABSTRACT A BRECHTIAN ANALYSIS OF CARYL CHURCHILL’S MAD FOREST AND EDWARD BOND’S RED, BLACK AND IGNORANT YÖNKUL, Ayşe M.A., in English Literature Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Hülya YILDIZ BAĞÇE January 2013, 94 Pages This thesis is primarily concerned with Caryl Churchill and Edward Bond’s attempts to implement Brechtian methods of Verfremdungseffekt with the same artistic intent of social change in their plays, Mad Forest and Red, Black and Ignorant. -

John Grisham a Time to Kill

John Grisham A Time to Kill Billy Ray Cobb was the younger and smaller of the two rednecks. At twenty-three he was already a three-year veteran of the state penitentiary at Parchm^an. Possession, with intent to sell. He was a lean, tough little punk who had survived prison by somehow maintaining a ready supply of drugs th^at he sold and sometimes gave to the blacks and the guards for protection. In the year since his release he had continued to prosper, and his small-time narcotics business had elevated him to the position of one of the more affluent rednecks in Ford County. He was a businessman, with employees, obligations, deals, everything but taxes. Down at the Ford place in Clanton he was known as the last man in recent history to pay cash for a new pickup truck. Sixteen thousand cash, for a custom-built, four-wheel drive, canary yellow, luxury Ford pickup. The fancy chrome wheels and mudgrip racing tires had been received in a business deal. The rebel flag hanging across the rear window had been stolen by Cobb from a drunken fraternity boy at an Ole Miss football game. The pickup was Billy Ray's most prized possession. He sat on the tailgate drinking a beer, smoking a joint, watching his friend Willard take his turn with the black girl. Willard was four years older and a dozen years slower. He was generally a harmless sort who had never been in serious trouble and had never been seriously employed. Maybe an occasional fight with a night in jail, but nothing that would distinguish him. -

About Endgame

BBC FILMS and ENDGAME ENTERTAINMENT present AN EDUCATION A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE Directed by LONE SCHERFIG Produced by FINOLA DWYER and AMANDA POSEY a FINOLA DWYER PRODUCTIONS / WILDGAZE FILMS Production Screenplay by NICK HORNBY adapted from a memoir by Lynn Barber Starring PETER SARSGAARD OLIVIA WILLIAMS CAREY MULLIGAN EMMA THOMPSON ALFRED MOLINA CARA SEYMOUR DOMINIC COOPER MATTHEW BEARD ROSAMUND PIKE SALLY HAWKINS *Official Selection: 2009 Sundance Film Festival *Winner - Audience Award, World Cinema Dramatic Competition, 2009 Sundance Film Festival *Winner - Cinematography Award, World Cinema Dramatic Competition, 2009 Sundance Film Festival East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP Public Relations Block‐Korenbrot PR Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Lindsay Macik 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 Tel : 212‐265‐4373 Tel : 323‐634‐7001 Tel : 212‐833‐8833 INTRODUCTION AN EDUCATION is the story of a teenage girl’s coming-of-age, set in Britain in the early 1960s on the cusp of the strait-laced, post-war period and the free-spirited decade to come. Directed by award-winning Danish filmmaker Lone Scherfig (Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself, Italian for Beginners) from a screenplay by Nick Hornby (High Fidelity, About a Boy) AN EDUCATION was adapted from a memoir by journalist Lynn Barber, which originally appeared in the literary magazine Granta. AN EDUCATION stars Peter Sarsgaard (Boys Don’t Cry, Kinsey, Shattered Glass), Carey Mulligan (Pride & Prejudice), Alfred Molina (Spiderman 2, Frida), Dominic Cooper (Mamma Mia!, The History Boys), Rosamund Pike (Fracture, Die Another Day), Cara Seymour (American Psycho, Gangs of New York), Olivia Williams (Rushmore, The Sixth Sense), Sally Hawkins (Happy-Go-Lucky (Golden Globe Winner)), and Emma Thompson (Last Chance Harvey, Primary Colors, Sense and Sensibility). -

The Ascent of Money: a Financial History of the World

NIALL FERGUSON Author of THE WAR OF THE WORLD THE ASCENT OF MONEY A FINANCIAL HISTORY of THE WORLD U.S. $29.95 Canada $33.00 Bread, cash, dosh, dough, loot: Call it what you like, it matters. To Christians, love of it is the root of all evil. To generals, it's the sinews of war. To revolu tionaries, it's the chains of labor. But in The Ascent of Money, Niall Ferguson shows that finance is in fact the foundation of human progress. What's more, he reveals financial history as the essential backstory behind all history. The evolution of credit and debt was as impor tant as any technological innovation in the rise of civilization, from ancient Babylon to the silver mines of Bolivia. Banks provided the material basis for the splendors of the Italian Renaissance while the bond market was the decisive factor in conflicts from the Seven Years' War to the American Civil War. With the clarity and verve for which he is known, Ferguson explains why the origins of the French Revolution lie in a stock market bubble caused by a convicted Scots murderer. He shows how financial failure turned Argentina from the world's sixth richest country into an inflation- ridden basket case—and how a financial revolution is propelling the world's most populous country from poverty to power in a single generation. Yet the most important lesson of the financial history is that sooner or later every bubble bursts —sooner or later the bearish sellers outnumber the bullish buyers, sooner or later greed flips into fear. -

List-Of-Drama-Sets.Pdf

Author Title Cast Length One Act Plays: Mixed Cast Agg, Howard A shot in the dark : a play in one act 3m, 5f Play: one act mixed Albee, Edward, 1928- The death of Bessie Smith 4m, 2f Play: one act mixed Albee, Edward, 1928- The zoo story, and other plays : The American dream; The death of Betty Smith; and,varies The sandboxPlay: one act mixed Auty, Stewart Absolute discretion : a one act play 5m, 9f Play: one act mixed Auty, Stewart An unassuming man : a one act play 4m, 4f Play: one act mixed Auty, Stewart Here endeth the first lesson : a one act satire 4m, 4f Play: one act mixed Ayckbourn, Alan, 1939- A cut in the rates 1m, 2f Play: one act mixed Ayckbourn, Alan, 1939- Confusions : five interlinked one-act plays 3m; 2f Play: one act mixed Ayckbourn, Alan, 1939- Confusions : five interlinked one-act plays 3m, 2f Play: one act mixed Barnes, Wilson Thicker than water : a play in one act 5m, 3f Play: one act mixed Barr, Russell A dish of tea with Dr Johnson 7m; 3f Play: one act mixed Barrie, J. M. (James Matthew), 1860-1937 Shall we join the ladies? 8m, 8f Play: one act mixed Bate, Sam Decline and fall : a play 3m, 5f Play: one act mixed Bellon, Loleh Thursday's ladies : a play 4f; 2m. Play: one act mixed Bennett, Alan, 1934- A visit from Miss Prothero : (from Office suite) 1m, 1f Play: one act mixed Bennett, Alan, 1934- Single spies : a double bill 9m, 2f Play: one act mixed Blair, Wilfrid, 1889-1968 For home - or country? : an extravaganza [in three scenes] 5f; 1m. -

A Play by James Anthony Tyler Starring Wendell Pierce And

SOME OLD BLACK MAN A Play by James Anthony Tyler Starring Wendell Pierce and Charlie Robinson Directed by Joe Cacaci UMS Digital Presentation Hosted on UMS.org Executive Producer / UMS Producer / 59th Limited Liability Company Friday Evening, January 15, 2021 at 7:00 (Digital Premiere) Streaming on demand through Monday, January 18 The Jam Handy Detroit, Michigan THANK YOU TO SUPPORTERS OF THIS UMS DIGITAL PRESENTATION Lead Presenting Sponsors TIM AND SALLY PETERSEN MICHIGAN ENGINEERING Presenting Sponsors DTE ENERGY FOUNDATION NEWMARKET LLC Patron Sponsor JERRY AND DALE KOLINS ENDOWMENT FUND Funded in part by COMMUNITY FOUNDATION FOR SOUTHEAST MICHIGAN UMS SUSTAINING DIRECTORS This digital presentation of Some Old Black Man is supported by Tim and Sally Petersen, Michigan Engineering, DTE Energy Foundation, Newmarket LLC, and the Jerry and Dale Kolins Endowment Fund. This digital presentation is also funded in part by the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan and the UMS Sustaining Directors. CAST Wendell Pierce / Calvin Jones, Ph.D. Charlie Robinson / Donald Jones CREATIVE TEAM Joe Cacaci / Director Justin Lang / Scenic and Lighting Design Suzanne Young / Costume Design Jim Lillie / Sound Design Tiffany Robinson / First Assistant Director Matt Hoffman / Director of Photography HMS Media / Editing and Post-Production This production runs approximately one hour and 45 minutes in duration and is performed without intermission. The world premiere of Some Old Black Man was produced by Berkshire Playwrights Lab and subsequently moved to 59E59 Theaters in New York City. 3 SYNOPSIS In Some Old Black Man, Calvin Jones (Wendell Pierce), a hip, coolly intellectual African American college professor, moves his 82-year-old ailing but doggedly independent father, Donald Jones (Charlie Robinson), from Greenwald, Mississippi into his Harlem penthouse. -

Year Title Author Genre 1997 Glowboys Lance Dann 1997

Year Title Author Genre 1997 Glowboys Lance Dann 1997 Riddley Walker (rpt, R4) Russell Hoban 1997 Playing the Wife Ronald Hayman 1997 Molly Sweeney Brian Friel 1997 The Importance of Being Earnest (rpt, R4) Oscar Wilde 1997 Proust Screen Play (rpt) Harold Pinter 1997 The Red Oleander Rabindranath Tagore 1997 The Tempest (rpt) Shakespeare 1997 Brahms on a Slow Train (rpt) David Pownall 1997 Pentecost (rpt) David Edgar 1997 Insignificance Terry Johnson 1997 My Dinner with Andre (rpt) Wally Shawn 1997 Fair Hearing (rpt) Steve May 1997 Outside the Door Wolfgang Borchert 1997 Roberto Zucco (rpt) Koltes/Mairowitz 1997 Spell No.7 (rpt, R4) Ntozake Shange 1997 The Sisterhood (rpt)] Moliere/Bolt 1997 Transit of Venus (rpt) Maureen Hunter 1997 Happy Days (rpt) Samuel Beckett 1997 Death in Venice Thomas Mann 1997 Blood Wedding (rpt) Federico Garcia Lorca 1997 The Libertine (rpt) Steven Jeffries 1997 Intimations for Saxophone (rpt) Sophie Treadwell 1997 Loot Joe Orton 1997 Up Against It Joe Orton 1997 The Merchant of Venice (rpt, R4) Shakespeare 1997 The Merry Wives of Windsor (rpt) Shakespeare 1997 The Relapse John Vanbrugh 1997 The Country Wife (rpt) William Wycherley 1997 Martin Yesterday Brad Fraser 1997 The Magistrate's Ordeal Robert Holman 1997 In Praise of Progress Gregory Motton 1997 The Country Martin Crimp 1997 Juno and the Paycock Sean O'Casey 1997 To the Wedding John Berger 1997 Antony and Cleopatra Shakespeare 1997 The Secret Commonwealth (rpt) John Purser 1997 Handel's Ghost Paul Barz/David Bryer 1997 The Winter's Tale Shakespeare 1998