Evaluation of the Union Learning Fund Rounds 15-16 and Support Role of Unionlearn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bio Testimony Combined

TABLE OF CONTENTS Thursday, May 14, 2020 William “Bill” Johnson Biography ................................................................................... 2 William “Bill” Johnson Testimony ................................................................................ 3-7 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment .......................................................................... 8-157 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ...................................................................... 158-169 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ...................................................................... 170-178 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ....................................................................... 179-193 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ....................................................................... 194-201 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ...................................................................... 202-203 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ............................................................................. 204 Mark Napier Biography ................................................................................................ 205 Mark Napier Testimony ......................................................................................... 206-210 Mark Napier Attachment ...................................................................................... 211-235 Michael Harrison Biography ......................................................................................... 236 Michael -

Managing Academic Staff in Changing University Systems: International Trends and Comparisons

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 586 HE 032 364 AUTHOR Farnham, David, Ed. TITLE Managing Academic Staff in Changing University Systems: International Trends and Comparisons. INSTITUTION Society for Research into Higher Education, Ltd., London (England). ISBN ISBN-0-335-19961-5 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 376p. AVAILABLE FROM Open University Press, 325 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106. Web site: <http://www.openup.co.uk>. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Faculty; Cross Cultural Studies; *Educational Administration; *Educational Policy; Foreign Countries; *Higher Education; Human Resources; Legislation; Public Policy; Teacher Salaries; Teaching (Occupation); Universities ABSTRACT This collection of 17 essays focuses on how faculty are employed, rewarded, and managed at universities in developed and developing nations. The essays, which include an introduction, 10 essays discussing European practices, two that focus on Canada and the United States, three which focus on Australia, Japan, and Malaysia, and a concluding chapter are: (1)"Managing Universities and Regulating Academic Labour Markets" (David Farnham); (2) "Belgium: Diverging Professions in Twin Communities" (Jef C. Verhoeven and Ilse Beuselinck); (3) "Finland: Searching for Performance and Flexibility" (Turo Virtanen); (4) "France: A Centrally-Driven Profession" (June Burnham); (5) "Germany: A Dual Academy" (Tassilo Herrschel); (6) "Ireland: A Two-Tier Structure" (Thomas N. Garavan, Patrick Gunnigle, and Michael Morley); (7) "Italy: A Corporation Controlling a System in Collapse" (William Brierley); (8) "The Netherlands: Reshaping the Employment Relationship" (Egbert de Weert); (9) "Spain: Old Elite or New Meritocracy?" (Salavador Parrado-Diez); (10) "Sweden: Professional Diversity in an Egalitarian System" (Berit Askling); (11) "The United Kingdom: End of the Donnish Dominion?" (David Farnham); (12) "Canada: Neo-Conservative Challenges to Faculty and Their Unions" (Donald C. -

For Unions the Future

the future for unions Tom Wilson This publication has been produced with the kind support of Russell Jones & Walker Solicitors. © No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing from Unions 21. Registered offi ce Unions 21 Swinton House 324 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8DD Contents Foreword – Debate 4 Biography – Tom Wilson 5 Summary 5 Introduction 6 A 9-point plan for growth 7 Union membership 12 Like recruits like: the importance of occupation 13 Public versus private 16 Equality and gender: the feminisation of the unions 18 Education 20 The changing shape of the union movement 21 Vulnerable workers 22 Students and young workers 24 The unions themselves 25 Size: to merge or not to merge? 30 What makes a successful union? 33 Appendix 34 Debate Unions 21 exists to provide an ‘open space’ for discussion on the future of the trade union movement and help build tomorrow’s unions in the UK. We are mainly resourced by contributions from trade unions and others who work with trade unions that recognise we need to keep the movement evolving in an ever changing world. We encourage discussion on tomorrow’s unions through publications, conferences, seminars and similar activities. The Debate series of publications present opinions upon the challenges trade unions are facing, solutions they may consider and best practice they may adopt. These opinions are not endorsed by Unions 21, but are published by us to encourage the much needed, sensible and realistic debate that is required if the trade union movement is going to prosper. -

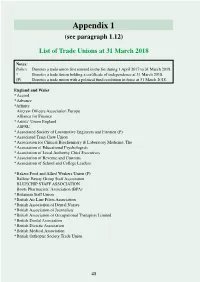

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

Taxpayer Funding of Trade Unions 2012-13

Research Note 140 | 10 September 2014 Taxpayer funding of trade unions 2012-13 Last year Cabinet Office Minister Francis Maude announced plans to reduce the amount of facility time taken by Civil Servants on Whitehall. This will cut the subsidy that unions receive at taxpayers’ expense. There is still be a substantial subsidy however, and the reforms do not yet apply to the broader public sector. As of April 2013, the Cabinet Office has been publishing facility time figures for central government departments online, an encouraging step towards transparency. Earlier TaxPayers’ Alliance research in this area revealed the extent of trade union subsidies across the public sector for the first time. This research updates that evidence of the huge amounts of taxpayers’ money given to trade unions through direct funding or paid staff time from public sector bodies. It contains information about the number of public sector bodies automatically deducting trade union subscriptions in the payroll process, often without charging the unions for that additional administrative support. The key findings of this research are: . Trade unions received a subsidy of at least £108 million at taxpayers’ expense in 2012-13. This is made up of an estimated £85 million in paid staff time, plus £23 million in direct payments. At least 2,841 full-time equivalent (FTE) public sector staff worked on trade union duties at taxpayers’ expense in 2012-13. The number of full-time equivalent staff provided to trade unions is 2.5 times as large as the workforce of HM Treasury.1 . 344 public sector organisations (out of the 1,074 surveyed) either did not fully record facility time or did not record it at all in 2012-13. -

Nominating Bodies This Details the Names of the Associations Or

Nominating bodies This details the names of the associations or organisations that we have listed to send information about nominating panel members or assessors for REF. However, any association or organisation with an interest in the conduct, quality, funding or use of research may make nominations to the REF panels (except individual UK HEIs, groups within or subsidiaries of individual HEIs, and HE mission groups). Associations or organisations with an interest in research who are not on this list, and who would like to receive information in future about nominating panel members and assessors, should contact [email protected]. -

GPC Report, Composite Motions and General Council Statements

CONGRESS 2017 GPC Report, Composite Motions and General Council Statements The 149th Annual Trades Union Congress 10–13 September 2017, Brighton CONTENTS SECTION 1 GPC REPORT TO CONGRESS 04 SECTION 2 CONGRESS TELLERS AND SCRUTINEERS 10 SECTION 3 COMPOSITE MOTIONS 01–12 11 SECTION 4 GENERAL COUNCIL STATEMENTS 30 CONTENTS 03 SECTION 1 GPC REPORT TO CONGRESS Part 1 Agenda All motions and amendments stand as in the Agenda unless indicated otherwise below. Where composite motions have been agreed and approved by the GPC by 6 September, they are shown in the list below and the text of the composite motion is given in Section 3 of this report. Composite motions agreed and approved by the GPC after 6 September will be reported to Congress by the GPC and copies circulated to delegates as quickly as possible. Where movers of motions have agreed to accept published amendments by 6 September, this is also stated in the list below. The GPC will report to Congress all instances where published amendments are accepted by the movers of motions after 6 September. The following is the position at 6 September in respect of motions, amendments and composite motions. Motion numbers are those printed in the Agenda. 1. THE ECONOMY 01 Unite Composite 01 A strong economy that works for all 02 ASLEF amend Community 03 UNISON Stands 04 FBU Stands 05 NAHT Stands amend NEU (NUT) accepted 06 BALPA Composite 02 amend CWU The safety risks of light- amend Prospect touch regulation amend RMT amend ASLEF 07 Community Stands amend TSSA withdrawn 08 Accord Composite 03 Rebuilding the finance sector 09 Aegis SECTION 1 GPC REPORT TO CONGRESS 04 10 BFAWU Composite 04 amend CWU Climate change amend FBU amend ASLEF amend TSSA 11 RMT Stands 12 Nautilus International Stands amend RMT accepted 13 Nautilus International Stands 14 TSSA Stands amend Unite accepted 15 Equity Stands 16 AUE Stands 17 TUC Trades Union Councils Stands Conference 2017 2. -

TUC Directory 2021

2021 CONTENTS SECTION 1 SECTION 4 About the TUC Trade unions Welcome 05 Union statistics 34 Who we are 06 TUC member unions 44 What we do 06 Confederations of unions 90 TUC priorities 2020–21 07 How the TUC works 08 SECTION 5 Committee membership 10 Skills, education and training SECTION 2 Learning through unions 94 TUC people TUC Education 98 Policy staff at Congress House 16 Policy staff in Wales and SECTION 6 the English regions 22 International relations ETUC affiliated unions 104 SECTION 3 ITUC regional organisations 107 TUC services ITUC global union federations 108 Helping unions grow and thrive 26 TUC Aid 110 TUC Information Service 28 TUC publications 28 SECTION 7 Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum 29 Calendar of events 111 TUC Library Collections 31 TUC archive 31 © James Brittain/Hugh Broughton Architects Broughton Brittain/Hugh James © SECTION 1 ABOUT THE TUC BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE WELCOME TO THE 2021 EDITION OF THE TUC DIRECTORY No-one could have foreseen the twin challenges of the global pandemic and consequent recession. We should be proud of the way the trade union movement responded, stepping up to fight the pandemic, demanding action to protect jobs and supporting our members through thick and thin. We showed the importance of unions standing up for working people. We adapted how we work and found new ways to build common purpose, understanding and solidarity when we couldn’t be physically together. We adopted the Organising Pledge that commits us to recruiting new members, seeking new recognitions and supporting a new generation of reps. -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2011-2012

8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page 1 CERTIFICATION OFFICE FOR TRADE UNIONS AND EMPLOYERS’ ASSOCIATIONS Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2011-2012 www.certoffice.org 8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page ii © Crown Copyright 2012 First published 2012 ii 8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page iii The Rt Hon Dr Vince Cable MP Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET Ed Sweeney Chair of ACAS Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3JJ I am required by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 to submit to you both a report on my activities as the Certification Officer during the previous reporting period. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012. DAVID COCKBURN The Certification Officer 13 June 2012 iii 8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page iv iv 8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page v Contents Page Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Lists of Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations 5 Entry in the lists and its significance 5 Unions and employers’ associations formed by an amalgamation 6 Trade unions and employers’ associations not on the lists (scheduled bodies) 6 Entry on the lists and schedules 6 Removal from the lists and schedules 7 Additions to the lists and schedules 8 Transfers from the schedules to the list 9 The lists and schedules at 31 March 2012 9 Special register bodies 9 Changes of name of listed trade unions -

UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT of ORAL EVIDENCE to Be Published As HC 94 HOUSE of COMMONS ORAL EVIDENCE TAKEN BEFORE the JUSTICE COMMITT

UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT OF ORAL EVIDENCE To be published as HC 94 HOUSE OF COMMONS ORAL EVIDENCE TAKEN BEFORE THE JUSTICE COMMITTEE CRIME REDUCTION POLICIES: A CO-ORDINATED APPROACH? WEDNESDAY 26 MARCH 2014 JEREMY WRIGHT MP and NORMAN BAKER MP Evidence heard in Public Questions 500 - 578 USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT 1. This is an uncorrected transcript of evidence taken in public and reported to the House. The transcript has been placed on the internet on the authority of the Committee, and copies have been made available by the Vote Office for the use of Members and others. 2. Any public use of, or reference to, the contents should make clear that neither witnesses nor Members have had the opportunity to correct the record. The transcript is not yet an approved formal record of these proceedings. 3. Members who receive this for the purpose of correcting questions addressed by them to witnesses are asked to send corrections to the Committee Assistant. 4. Prospective witnesses may receive this in preparation for any written or oral evidence they may in due course give to the Committee. 1 Oral Evidence Taken before the Justice Committee on Wednesday 26 March 2014 Members present: Sir Alan Beith (Chair) Steve Brine Jeremy Corbyn Nick de Bois Mr Elfyn Llwyd Andy McDonald John McDonnell ________________ Examination of Witnesses Witnesses: Jeremy Wright MP, Prisons and Probation Minister, Ministry of Justice, and Norman Baker MP, Minister for Crime Prevention, Home Office, gave evidence. Q500 Chair: Mr Wright and Mr Baker, welcome. We are continuing with our inquiry into the wider issues that were initially raised in the Committee’s report back in 2010 and the ways in which these have either been implemented or not. -

Appendix 5 (See Paragraph 4.21) Salary and Benefits of Trade Union General Secretaries

Appendix 5 (see paragraph 4.21) Salary and Benefits of Trade Union General Secretaries Title Salary Benefits (General Secretary £ £ unless otherwise stated) England and Wales Accord General Secretary 118,518 20,828 Advance General Secretary 15,699 3,959 Affinity General Secretary 84,000 29,250 Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen General Secretary 94,425 23,170 Association of Educational Psychologists General Secretary 65,132 7,040 Association of School and College Leaders General Secretary 119,054 (a) 115,944 (a) (b) Association of Teachers and Lecturers General Secretary 123,765 (c) 18,358 (c) Association of Trade Union Political and Public Sector Staff Acting General Secretary 100 0 Bakers, Food and Allied Workers’ Union General Secretary 47,384 16,708 Bluechip Staff Association General Secretary 30,031 0 Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA), The Chief Executive Officer 0 20,280 (d) Britannia Staff Association General Secretary 67,656 11,548 British Air Line Pilots Association General Secretary 121,434 18,614 British Association of Journalists General Secretary 31,589 (a) 0 British Dental Association General Secretary 75,000 0 British Medical Association Chairman 40,348 0 Broadcasting Entertainment Cinematograph and Theatre Union General Secretary 70,806 8,039 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Chief Executive 120,000 20,670 Communication Workers Union General Secretary 89,933 26,640 Community General Secretary 109,003 31,471 Confederation of Shipbuilding and Engineering Unions General Secretary 80,720 21,122 62 Curry’s -

A Joint Report by Bio Ventures for Global Health Bvgh & the Biotechnology

BIOTECHNOLOGY BRINGING INNOVATION TO NEGLECTED DISEASE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT A Joint Report by BIOTECHNOLOGY BIO Ventures for Global Health (BVGH) & the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) Bringing Innovation to Neglected Disease JUNE 2012 Research and Development BIO Ventures for Global Health (BVGH) Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) 221 Main Street, Suite 1600 1201 Maryland Avenue SW, Suite 900 San Francisco, California 94105 Washington, District of Columbia 20024 United States United States JUNE 2012 Phone/Fax: +1 415-446-9440 Phone: 202.962.9200 Fax: 202.488.6301 (f) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.bvgh.org www.bio.org For further copies, please contact BIO Ventures for Global Health at [email protected]. A JOINT REPORT BY Copyright © June 2012 BIO Ventures for Global Health BIO VENTURES FOR GLOBAL HEALTH BVGH & All rights reserved THE BIOTECHNOLOGY INDUSTRY ORGANIZATION BIO BIOTECHNOLOGY BRINGING INNOVATION TO NEGLECTED DISEASE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT A JOINT REPORT BY BIO VENTURES FOR GLOBAL HEALTH BVGH & THE BIOTECHNOLOGY INDUSTRY ORGANIZATION BIO JUNE 2012 BIO Ventures for Global Health (BVGH) Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) 221 Main Street, Suite 1600 1201 Maryland Avenue SW, Suite 900 San Francisco, California 94105 Washington, District of Columbia 20024 United States United States For further copies, please contact BIO Ventures for Global Health at [email protected]. Copyright © June 2012 BIO Ventures for Global Health All rights reserved BIO Ventures for Global Health (BVGH) and the Biotechnology