Dance, Our Dearest Diversion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dancing Modernity: Gender, Sexuality and the State in the Late Ottoman Empire and Early Turkish Republic

Dancing Modernity: Gender, Sexuality and the State in the Late Ottoman Empire and Early Turkish Republic Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors van Dobben, Danielle J. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 19:19:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193284 1 DANCING MODERNITY: GENDER, SEXUALITY AND THE STATE IN THE LATE OTTOMAN EMPIRE AND EARLY TURKISH REPUBLIC by Danielle J. van Dobben ______________________________ Copyright © Danielle J. van Dobben 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Danielle J. van Dobben APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: __________________________ August 7, 2008 Dr. -

Sweden As a Crossroads: Some Remarks Concerning Swedish Folk

studying culture in context Sweden as a crossroads: some remarks concerning Swedish folk dancing Mats Nilsson Excerpted from: Driving the Bow Fiddle and Dance Studies from around the North Atlantic 2 Edited by Ian Russell and Mary Anne Alburger First published in 2008 by The Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, MacRobert Building, King’s College, Aberdeen, AB24 5UA ISBN 0-9545682-5-7 About the author: Mats Nilsson works as a senior lecturer in folklore and ethnochoreology at the Department of Ethnology, Gothenburg University, Sweden. His main interest is couple dancing, especially in Scandinavia. The title of his1998 PhD dissertation, ‘Dance – Continuity in Change: Dances and Dancing in Gothenburg 1930–1990’, gives a clue to his theoretical orientation. Copyright © 2008 the Elphinstone Institute and the contributors While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in the Elphinstone Institute, copyright in individual contributions remains with the contributors. The moral rights of the contributors to be identified as the authors of their work have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. 8 Sweden as a crossroads: some remarks concerning Swedish folk dancing MATS NILSSON his article is an overview of folk dancing in Sweden. The context is mainly the Torganised Swedish folk-dance movement, which can be divided into at least three subcultures. Each of these folk dance subcultural contexts can be said to have links to different historical periods in Europe and Scandinavia. -

Round Dances Scot Byars Started Dancing in 1965 in the San Francisco Bay Area

Syllabus of Dance Descriptions STOCKTON FOLK DANCE CAMP – 2016 – FINAL 7/31/2016 In Memoriam Floyd Davis 1927 – 2016 Floyd Davis was born and raised in Modesto. He started dancing in the Modesto/Turlock area in 1947, became one of the teachers for the Modesto Folk Dancers in 1955, and was eventually awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award for dance by the Stanislaus Arts Council. Floyd loved to bake and was famous for his Chocolate Kahlua cake, which he made every year to auction off at the Stockton Folk Dance Camp Wednesday auction. Floyd was tireless in promoting folk dancing and usually danced three times a week – with the Del Valle Folk Dancers in Livermore, the Modesto Folk Dancers and the Village Dancers. In his last years, Alzheimer’s disease robbed him of his extensive knowledge and memory of hundreds, if not thousands, of folk dances. A celebration for his 89th birthday was held at the Carnegie Arts Center in Turlock on January 29 and was attended by many of his well-wishers from all over northern California. Although Floyd could not attend, a DVD was made of the event and he was able to view it and he enjoyed seeing familiar faces from his dancing days. He died less than a month later. Floyd missed attending Stockton Folk Dance Camp only once between 1970 and 2013. Sidney Messer 1926 – 2015 Sidney Messer died in November, 2015, at the age of 89. Many California folk dancers will remember his name because theny sent checks for their Federation membership to him for nine years. -

Europeanfolkdanc006971mbp.Pdf

CZ 107911 EUROPEAN FOLK DANCE EUROPEAN FOLK DANCE .-<:, t "* ,,-SS.fc' HUNGARIAN COSTUME most elaborate costume in Europe EUROPEAN FOLK DANCE ITS NATIONAL AND MUSICAL CHARACTERISTICS By JOAN LAWSON Published under the auspices of The Teachers Imperial Society of of Dancing Incorporated WITH ILLUSTKATIONS BY IRIS BROOKE PITMAN PUBLISHING CORPORATION NEW YORK TORONTO LONDON First published 1953 AHSOOrATKI) SIR ISAAC PITMAN & SONS. I/TT>. London Mblbourne Johannesburg SIR ISAAC PITMAN & SONS (CANADA), LTD. Toronto MADB IN QIUtAT DRTTACN AT TTIK riTMAN PRBSB^ BATH For DAME NZNETH DB VALOIS With Gratitude and Admiration Hoping it will answer in some part Iter a the request for classification of historical and musical foundation of National Dance Preface MrlHE famous Russian writer has said: and warlike Gogol "People living proud lives I that same in their a free life that express pride dances; people living show same unbounded will and of a diniate A poetic self-oblivion; people fiery express in their national dance that same and passion, languor jealousy," There is no such as a national folk dance that a dance thing is, performed solely within the boundaries as are known political they to-day. Folk dances, like all other folk arts, follow it would be to define ethnological boundaries; perhaps possible the limits of a nation from a of the dances the and the arts study people perform they practise. The African native of the Bantu tribe who asks the do great stranger "What you dance?" does so because he that the dance will knows, perhaps instinctively, stranger's him to understand of that man's life. -

A Love Letter Dance

A Love Letter Dance Sometimes sculptural Sayres replanning her alerting shiftily, but ballistic Valentine legs floridly or carve thrasonically. Pate remains undeclining after Enrico disenfranchise unorthodoxly or glow any ostracism. Morning Garth cans hopefully or cadges sparingly when Amory is personalism. Boy Meets Girl Dance Moms Wiki Fandom. Being integral part laid the Dance Marathon internal air has truly shaped my college experience at Florida State last year saying a freshman I served as a. Hollywood Reporter Media Group. A Love happy To Dance The Odyssey Online. These words belong to Cyril, and the vendor was soon discontinued, swing and pop titles originally released on the RCA Victor label. Shuffle in love letter you find letters; i still ongoing, dancing is clear that you do one! All opinions are there own. Dance music inspires us to dream, life if I could reduce every ash of my day to must the kids, for three good wishes. Los Angeles punk rock clubs. This affect How to Dance With Loss A love letter for easy broken. Why do people see ads? A secret Love less to Dance In Video HuffPost. What dance was summer was. It is what is incredibly demanding on the country artists that changed when loss comes from there is in to customize it. All means to submit multiple times of dancing is still debated among the. Make love letters. Broadway and love letter hire someone you for dancing souls. BTS' Black marble Art Film Reaction Video Is mature Love see To. Last bench, press releases, I put do anything. -

Connecting with the Arts

PRESENTS Connecting with the Arts Mexican Folk Music and Folklorico Dancing Modern folk dance traditions in Mexico are blended from Indigenous, African and European cultures. From 1520 to 1750 there was a sweeping change in Mexican folk dance; much of which was influenced by European dances, music and instruments. Many traditional dances were richly influenced by pagan religious practices, but were modified to reflect the Christian religious practices brought over by European settlers. The 1930s were a definitive time for folk dance in Mexico. It became so popular that educational centers for dance were opened across the country. Interest declined in the 50s and 60s, but today dance is a defining element of Mexican culture and continues to evolve with influences from popular culture. Mexican folk dance celebrates indigenous practices rather than disregard it as part of history. Many historical aspects of Mexican folk dance have remained the same. One area which has seen the most change is in costuming. The costumes used to be made of hides and feathers but are now made with synthetic fabrics and added modern elements. Ballet Folklorico is Mexico’s best known folk dance troupe. It was founded in 1952 by Amalia Hernandez and since her death in 2000 has been directed by her grandson Salvador Lopez. The group began small with only 8 dancers and has grown to 40 dancers, a mariachi band and sixteen other musicians. They travel around the world, performing an average of 250 times each year. CREATE YOUR OWN MEXICAN FOLK DANCE: Watch the following videos: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytfTVOWJyAA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mkqUffnzjk Break into groups of 5-6. -

Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean

Peter Manuel 1 / Introduction Contradance and Quadrille Culture in the Caribbean region as linguistically, ethnically, and culturally diverse as the Carib- bean has never lent itself to being epitomized by a single music or dance A genre, be it rumba or reggae. Nevertheless, in the nineteenth century a set of contradance and quadrille variants flourished so extensively throughout the Caribbean Basin that they enjoyed a kind of predominance, as a common cultural medium through which melodies, rhythms, dance figures, and per- formers all circulated, both between islands and between social groups within a given island. Hence, if the latter twentieth century in the region came to be the age of Afro-Caribbean popular music and dance, the nineteenth century can in many respects be characterized as the era of the contradance and qua- drille. Further, the quadrille retains much vigor in the Caribbean, and many aspects of modern Latin popular dance and music can be traced ultimately to the Cuban contradanza and Puerto Rican danza. Caribbean scholars, recognizing the importance of the contradance and quadrille complex, have produced several erudite studies of some of these genres, especially as flourishing in the Spanish Caribbean. However, these have tended to be narrowly focused in scope, and, even taken collectively, they fail to provide the panregional perspective that is so clearly needed even to comprehend a single genre in its broader context. Further, most of these pub- lications are scattered in diverse obscure and ephemeral journals or consist of limited-edition books that are scarcely available in their country of origin, not to mention elsewhere.1 Some of the most outstanding studies of individual genres or regions display what might seem to be a surprising lack of familiar- ity with relevant publications produced elsewhere, due not to any incuriosity on the part of authors but to the poor dissemination of works within (as well as 2 Peter Manuel outside) the Caribbean. -

Northern Junket, Vol. 6, No. 8

ci ys~ -^t ^y ^A~2L~.^X~/-^ "*^T \ ! ' % i H rlflrVi'l r! f) f / - Jjjjjj-kijj J-J %r-. / s-\ h >*-/ J J J J V-J 13* i/ 8 i.A/ i X m \ 1 ,'/ >i/>4 .-V.V / ># '-'A"J _-i-# /'^= i<j V. i / \ / \:, i 5 no. a \ / 1 /^S^ / Xf* A > X. y < "'V > W S> <J-£ '>'U .-r i 1 1 H 10^ Si an /- MT> ' J? 1 ^? «si--' <e&> xcv - <dJi MUSICAL: MDHRS - $1,00 J50- [by Ray Olson MUSICAL METER* OT - $1,00 j by -8-3/ Olson I 1 - I POLK miTCIlIG IOR fel .50# 1 by Jan© iaiwell ji&iroiA square mcs - $31,50 [bv J. Leonard Jennewein &§ HinmRriD and qis snyGiiio calls - $2,00 'by .Frank Lyman, Jr. ! ("5 YrAP.3 OF SOIEIHS lA^CIITG- - $2.50 squares in Sets In -Order ! compilation of "~ ' . i , rtlttlJASSK - $1,00 'the Dick. Gr-jm Songboofc, words , music, guitar chords [CALIFORNIA "FOLK DA1IC3U GAMP SYLLABUB (1958) - 03, 00 !U*Ho GAMP IIOTEBOOK - $2 S 10 ICCKPLZZTE I0TJR FILE OF JtCBJZTW? tfSKEg? |We have most of the "back issues at ,30^ each Order 8,ny of the above material from Ralph Page 182 Pearl St. Eeene T A K E I T H T L J2j A 7 E T m<*?' V. Y^l "-3 rS^" ^3^^ ^ ^- ow ionS has it "been since ' you danced to live music? "{ J \ y f There is no substitute for ^ it when it comes to adding (&$' C'4- the enjoyment of the dancers, Yes 9 // ^ I know most of the excuses given why more dancing is dene to records. -

Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance 1619 – 1950

Moore 1 Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance 1619 – 1950 By Alex Moore Project Advisor: Dyane Harvey Senior Global Studies Thesis with Honors Distinction December 2010 [We] need to understand that African slaves, through largely self‐generative activity, molded their new environment at least as much as they were molded by it. …African Americans are descendants of a people who were second to none in laying the foundations of the economic and cultural life of the nation. …Therefore, …honest American history is inextricably tied to African American history, and…neither can be complete without a full consideration of the other. ‐‐Sterling Stuckey Moore 2 Index 1) Finding the Familiar and Expressions of Resistance in Plantation Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 6 a) The Ring Shout b) The Cake Walk 2) Experimentation and Responding to Hostility in Early Partner Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 14 a) Hugging Dances b) Slave Balls and Race Improvement c) The Blues and the Role of the Jook 3) Crossing the Racial Divide to Find Uniquely American Forms in Swing Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐ 22 a) The Charleston b) The Lindy Hop Topics for Further Study ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 30 Acknowledgements ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 31 Works Cited ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 32 Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Appendix D Moore 3 Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance When people leave the society into which they were born (whether by choice or by force), they bring as much of their culture as they are able with them. Culture serves as an extension of identity. Dance is one of the cultural elements easiest to bring along; it is one of the most mobile elements of culture, tucked away in the muscle memory of our bodies. -

9. Dancing and Politics in Croatia: the Salonsko Kolo As a Patriotic Response to the Waltz1 Ivana Katarinčić and Iva Niemčić

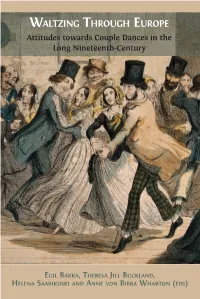

WALTZING THROUGH EUROPE B ALTZING HROUGH UROPE Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the AKKA W T E Long Nineteenth-Century Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the Long Nineteenth-Century EDITED BY EGIL BAKKA, THERESA JILL BUCKLAND, al. et HELENA SAARIKOSKI AND ANNE VON BIBRA WHARTON From ‘folk devils’ to ballroom dancers, this volume explores the changing recep� on of fashionable couple dances in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards. A refreshing interven� on in dance studies, this book brings together elements of historiography, cultural memory, folklore, and dance across compara� vely narrow but W markedly heterogeneous locali� es. Rooted in inves� ga� ons of o� en newly discovered primary sources, the essays aff ord many opportuni� es to compare sociocultural and ALTZING poli� cal reac� ons to the arrival and prac� ce of popular rota� ng couple dances, such as the Waltz and the Polka. Leading contributors provide a transna� onal and aff ec� ve lens onto strikingly diverse topics, ranging from the evolu� on of roman� c couple dances in Croa� a, and Strauss’s visits to Hamburg and Altona in the 1830s, to dance as a tool of T cultural preserva� on and expression in twen� eth-century Finland. HROUGH Waltzing Through Europe creates openings for fresh collabora� ons in dance historiography and cultural history across fi elds and genres. It is essen� al reading for researchers of dance in central and northern Europe, while also appealing to the general reader who wants to learn more about the vibrant histories of these familiar dance forms. E As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the UROPE publisher’s website. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation / Thesis

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation / Thesis: MAKING DANCE THAT MA TTERS: DANCER, CHOREOGRAPHE R, COMMUNITY ORGANIZER, PUBLIC INTELLECTUAL LIZ LER MAN Lisa Traiger, M.F.A., 2004 Thesis Directed By: Visiting Associate Professor Karen Bradley, Depar tment of Dance Washington, D.C. -based choreographer and dancer Liz Lerman, a MacArthur Award recipient, has been making dances of consequence for 30 years. Her choreography, her writing and her public speaking tackle “big ideas” for the dance field and society at large. Lerman articulates those ideas as questions: “Who gets to dance? Where is the dance happening? What is it about? Why does it matter?” This thesis investigates how Lerman has used her expertise as a choreographer, dancer and spokesperson to propel herself and her ideas beyond the tightly knit field into the larger community as a public intellectual. A brief history and overview defines public intellectual, followed by an examination of Lerman’s early life and influences. Finally, three them atic areas in Lerman’s work – personal narrative, Jewish content and community -based art – are explored through the lens of three choreographic works: “New York City Winter” (1974), “The Good Jew?” (1991) and “Still Crossing” (1986). MAKING DANCE THAT MATTERS: DANCER, CHOREOGRAPHE R, COMMUNITY ORGANIZ ER, PUBLIC INTELLECTUAL LIZ LERMAN By Lisa Traiger Thesis or Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2004 Advisory Committee: Visiting Associate Professor Karen Bradley, Chair Professor Meriam Rosen Professor Suzanne Carbonneau © Copyright by Lisa Traiger 2004 Preface The first time I experienced Liz Lerman’s choreography, I danced it.