Traffic Congestion Around Schools by Nancy G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DMV Driver Manual

New Hampshire Driver Manual i 6WDWHRI1HZ+DPSVKLUH DEPARTMENT OF SAFETY DIVISION OF MOTOR VEHICLES MESSAGE FROM THE DIVISION OF MOTOR VEHICLES Driving a motor vehicle on New Hampshire roadways is a privilege and as motorists, we all share the responsibility for safe roadways. Safe drivers and safe vehicles make for safe roadways and we are pleased to provide you with this driver manual to assist you in learning New Hampshire’s motor vehicle laws, rules of the road, and safe driving guidelines, so that you can begin your journey of becoming a safe driver. The information in this manual will not only help you navigate through the process of obtaining a New Hampshire driver license, but it will highlight safe driving tips and techniques that can help prevent accidents and may even save a life. One of your many responsibilities as a driver will include being familiar with the New Hampshire motor vehicle laws. This manual includes a review of the laws, rules and regulations that directly or indirectly affect you as the operator of a motor vehicle. Driving is a task that requires your full attention. As a New Hampshire driver, you should be prepared for changes in the weather and road conditions, which can be a challenge even for an experienced driver. This manual reviews driving emergencies and actions that the driver may take in order to avoid a major collision. No one knows when an emergency situation will arise and your ability to react to a situation depends on your alertness. Many factors, such as impaired vision, fatigue, alcohol or drugs will impact your ability to drive safely. -

School Zone Safety

Best Practices for Safe Drop Off/Pick Up • Use only designated drop off locations – each school has a School Zone Facts designated location to drop off and pick up kids; drivers should use only that location. • Accident statistics show that roughly • Do not park across the street from the drop location – hav- 26 kids die every year in school bus ing kids crossing the streets mid-block is dangerous, especially SCHOOL ZONE with all the other cars coming in to drop off kids, and it’s unfair accidents, are hurt while getting off the to nearby neighbors who may already be experiencing high SAFETY bus or hurt as passengers. levels of traffic. • Do not use the school’s bus loading zone – this zone is for • Most young children are injured school buses only, and dropping kids off at this location is not near their home or on their own only dangerous, it also slows down the flow of all the other street. cars, and any buses coming in. • Allow extra time – everyone is very busy, but that’s no excuse • Most crashes involving young chil- to put our kids’ safety at risk – leave a few minutes early to dren occur between 3 p.m. and 6 allow ample time for drop off and pick up. Just a few minutes can make a great difference, and help to make the traffic circu- p.m. lation around schools more efficient for everyone. • Be courteous and respectful of neighbors – you can reduce • Most crashes involving young chil- the traffic and parking impact on residents living near a school dren occur in fair and warm drop off location by following all procedures, and by being sure weather. -

Indiana Drivers Manual: Ch. 7

CHAPTER 7 | Safe Vehicle Operation CHAPTER SEVEN | SAFE VEHICLE OPERATION Even the most experienced drivers can be distracted while driving. A defensive driver looks out for the actions of other drivers and anticipates potential problems. LANE MARKINGS Lane markings separate traffic and alert drivers when it is permissible to pass other vehicles. Yellow Lane Markings Yellow lane markings separate multiple lanes of traffic going in opposite directions. You may cross a broken yellow line to pass another vehicle when it is safe, but you should not cross a solid yellow line except to turn. Two-lane road with a solid yellow line Two-lane road with a broken Four-lane road with a solid yellow line yellow line White Lane Markings White lane markings separate multiple lanes of traffic going in the same direction. Most roads with more than two lanes have broken white lines to separate the lanes. You may cross a broken white line when it is safe to change lanes, but you should not cross a solid white line. Three lanes of traffic with broken white lines CHANGING LANES AND PASSING OTHER VEHICLES Change only one lane at a time. When changing lanes to prepare for a turn, you must signal your intention to do so at least 200 feet prior to changing lanes or turning. Your signal distance must be at least 300 feet before the turn if you are operating a vehicle in a speed zone of at least 50 miles per hour. Do not weave in and out of lanes, which will greatly increase your risk of an accident. -

An Evaluation of School Zone Traffic Control Strategies, Phase I

An Evaluation of School Zone Traffic Control Strategies, Phase I Morgan State University The Pennsylvania State University University of Maryland University of Virginia Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University West Virginia University The Pennsylvania State University The Thomas D. Larson Pennsylvania Transportation Institute Transportation Research Building University Park, PA 16802-4710 Phone: 814-865-1891 Fax: 814-863-3707 www.mautc.psu.edu An Evaluation of School Zone Traffic Control Strategies, Phase I West Virginia Department of Transportation Research Project # 279 By Karly Hamric David R. Martinelli Avinash Unnikrishnan Diana Martinelli Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering West Virginia University Morgantown, WV 26505 USA The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the state or the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Trade or manufacturers’ names which may appear herein are cited only because they are considered essential to the objectives of this report. The United States Government and the State of West Virginia do not endorse products of manufacturers. Prepared for the West Virginia Department of Transportation, Division of Highways, in cooperation with the US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. [THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. WVU-2010-02 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date March 2013 An Evaluation of School Zone Traffic Control Strategies, Phase I 6. Performing Organization Code 7. -

HB1401 INT.Pdf

STATE OF OKLAHOMA 1st Session of the 43rd Legislature (1991) HOUSE BILL NO. 1401 BY: HUDSON AS INTRODUCED AN ACT RELATING TO CITIES AND TOWNS AND MOTOR VEHICLES; AMENDING 11 O.S. 1981, SECTION 22-117, WHICH RELATES TO TRAFFIC REGULATIONS OF MUNICIPALITIES; REQUIRING MUNICIPALITIES TO CREATE NO-PASSING ZONES IN SCHOOL ZONES; AMENDING 47 O.S. 1981, SECTIONS 11-307, 11-705, AS AMENDED BY SECTION 1, CHAPTER 207, O.S.L. 1989, AND 11-801 (47 O.S. SUPP. 1990, SECTION 11-705), WHICH RELATE TO NO-PASSING ZONES, MEETING OR OVERTAKING SCHOOL BUSES AND BASIC RULES AND MAXIMUM SPEED LIMITS; REQUIRING DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY TO DECLARE SCHOOL ZONES AS NO-PASSING ZONES AND TO CAUSE APPROPRIATE SIGNS TO BE PLACED MARKING SUCH ZONES; STRIKING LANGUAGE RELATING TO OVERTAKING A SCHOOL BUS; REQUIRING DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY TO MARK SPEED ZONES AS NO-PASSING ZONES; AND PROVIDING AN EFFECTIVE DATE. BE IT ENACTED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA: SECTION 1. AMENDATORY 11 O.S. 1981, Section 22-117, is amended to read as follows: Section 22-117. A. The municipal governing body may establish ordinances and regulations governing the operation of motor vehicles and traffic upon the roads and streets within the municipality in the manner provided by, and not inconsistent with, state law. The governing body may also regulate and prevent racing and fast driving, and all games, practices or amusements likely to result in damage to any person or property, in the streets, highways, alleys, bridges, sidewalks or other places in the municipality, and riding or driving over or upon the sidewalks of the municipality. -

City's School Zone Traffic Control Policy

School Zone Traffic Control Policy CITY OF BILLINGS SCHOOL ZONE TRAFFIC CONTROL POLICY (Approved by Traffic Control Board 10/27/99 ) (Approved by Billings City Council on 6/25/01 ) I. GEERAL This policy has been established for use as a guide in determining where school crossings should be located and what other traffic control devices may be appropriate for a given school zone or crossing. This policy is intended to supplement the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices , the "School Trip Safety Program Guidelines" and "A Program for School Crossing Protection" recommended practices published by the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE), and the "School Crossing Protection Manual" published by the Montana Office of Public Instruction. The warrants listed are not meant to be hard and fast limits, and are not a substitute for engineering judgment. The following statements taken from the "School Crossing Protection Manual" are central to the application of this policy: Children must be taught that they alone are responsible for their safety and that they must be vigilant at all times. They must be convinced that a traffic sign, a traffic signal, or even a school crossing supervisor does not relieve them of that responsibility; that all street crossing locations are dangerous; and that only through safe crossing habits and practices will they remain safe. It is also important that children be taught to walk correctly on sidewalks and, when they are not available, to walk on the shoulder or the far left side of the street or highway. Most children of school age are injured or killed at locations other than at school crossings and other than when going to and from school. -

Summary of State Speed Laws

DOT HS 810 826 August 2007 Summary of State Speed Laws Tenth Edition Current as of January 1, 2007 This document is available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161 This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers' names or products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................iii Missouri ......................................................138 Alabama..........................................................1 Montana ......................................................143 Alaska.............................................................5 Nebraska .....................................................150 Arizona ...........................................................9 Nevada ........................................................157 Arkansas .......................................................15 New -

Alarming Dangers in School Zones, 2016

Alarming Dangers in School Zones October 2016 Alarming Dangers in School Zones The Facts About Teen Pedestrians Age 15-19 In 2015, while teens ages 15-19 week 5 / 13% made up 26 percent of all There are 5 teen pedestrian There has been a children ages 0-19 years, they deaths every week in the 13% increase in the made up about half of the United States. pedestrian death rate pedestrian fatalities. for 12-19 year olds since 2013. population pedestrian deaths We observed 39,000 middle and high school students and 56,000 drivers in school zones in 2016. Distracted walking is Distracted teens Unsafe street crossing Unsafe drop-o or on the rise. We observed it were most likely to be wearing behavior was observed in pick-up behavior was in 1 in 4 high school students headphones or texting. about 80% of students. observed in nearly and 1 in 6 middle school 1 in 3 drivers. students. 44% 1 in 4 l o o h h sc igh l 1 in 6 o o h sc m iddle 31% What Communities Can Do to Protect Kids on the Move Install proven Set and enforce speed Implement and interventions, like limits in school zones at enforce school crosswalks, speed no more than 20 mph. drop-o/pick-up limits, visible signs policies. Low speed limits and trac lights. (≤20 mph) were Educate parents Marked crosswalks were observed in only and students about missing in 3 out of 10 about 4 out of 10 dangerous walking observed crossings. -

Fewer People Speeding

FOCUS AREA FEWER PEOPLE SPEEDING DID YOU KNOW.... One out of every three collisions in our city involves speeding 1715 MEASURES Number of collisions attributed to speeding annually 479 (2010) Speed-involved collisions resulting in fatalities 42 percent (2006-2010) Identified corridors where 85th percentile speeds are at or below the posted speed limit 30 percent (2010) Speeding creates undesirable conditions for everyone. Unfortunately, data shows that speeding has had a People driving the speed limit sometimes end up being tragic toll on our roadways. Between 2006 and 2010, tailgated, dealing with aggressive drivers weaving in and speeding was a factor in 42 percent of fatality collisions out of traffic, or being pressured into driving faster. in Seattle. This often leads to road rage or worse – a collision. Conditions for walkers and bikers deteriorate with Speed is especially lethal for vulnerable users like speed as well. Crossing a street where cars routinely pedestrians and people on bikes. A pedestrian hit at speed can seem insurmountable to pedestrians and 40 miles per hour has an 85 percent chance of dying. people on bikes; especially children and seniors. Pedestrians are much more likely to survive a collision with a vehicle at 20 miles per From busy arterial streets like Vehicle traveling at hour. Keep in mind that speed Rainier Avenue South to low has very little influence on the volume neighborhood streets, likelihood of an injury when 9 out of 10 pedestrians survive. speeding is a persistent traffic pedestrians or cyclists are safety issue in Seattle. One Vehicle traveling at hit by a vehicle – the chance out of every three collisions of injury remains near 100 in our city involves speeding. -

CHAPTER 3: LEARNING to DRIVE This Chapter Provides Information That Will Help You Become a Safe Driver

Chapter 3 - Learning to Drive PA Driver’s Manual CHAPTER 3: LEARNING TO DRIVE This chapter provides information that will help you become a safe driver. It covers these topics: • Choosing Safety First • Driver Factors • Everyday Driving Skills • Special Circumstances and Emergencies CHOOSING SAFETY FIRST You have important choices to make – sometimes even before you start your vehicle – that will affect your safety when you are behind the wheel. Begin by making sure you and your vehicle are “fit to drive.” VEHICLE CHECKS: PREPARING TO DRIVE 1. Adjust the driver’s seat – You must be able to easily reach the pedals and other controls and have a clear view out the windshield. Your owner’s manual provides information about how to adjust your vehicle’s equipment. 2. Fasten your seat belt – Fasten both your lap and shoulder belts on every trip. Pay attention to the information about Pennsylvania’s seat belt law, child restraint law and airbag safety information found in Chapter 5. DID YOU KNOW? WEARING YOUR SEAT BELT In 2011, 78 percent of people involved in crashes in Pennsylvania is the single most effective were wearing seat belts. Drivers, ages 16 to 24, had the highest thing you can do to reduce number of unbuckled injuries and fatalities of any age group and the the risk of death or injury! lowest seat belt use. 3. Secure loose items in the passenger compartment – In a crash, loose items in your vehicle become projectiles that continue to travel the same speed your vehicle was moving before the impact. Put heavier objects, such as backpacks, luggage and tools in your trunk, whenever possible, or secure them with the vehicle’s seat belts. -

Creating a Safe, Effective School Zone Traffic Plan

December 2013 Best Practices in School Zone Traffic Calming Creating a Safe, Effective School Zone Traffic Plan Each year, an estimated 100 children are killed in the U.S. as they make their way to and from school, and some 21,000 students are injured from incidents in school zones. The primary factor in these events is speeding. Unfortunately, twothirds of drivers exceed the legal speed limit when passing through these zones. As higher vehicle speeds are directly correlated to increased rates of pedestrian fatalities (NHTSA), it is imperative that drivers adhere to posted speed limits to avoid the tragic loss of life in school zones. While speeding is the primary cause of school zone injuries, other driver behaviors pose a threat to children here, too: ● “Autopilot” driving “Familiarity breeds inattention,” according to a Churchill Insurance Study which found that 46% of drivers say they are most likely to have no recollection of how they got to their destination during “autopilot journeys,” those regular trips on familiar routes. Importantly, 7% percent of motorists say they are most likely to switch to autopilot while “doing the school run.” ● Distracted driving One in six drivers (17%) are distracted, operating with a slower reaction time further increasing the probability of tragedy in school zones. Combine these driver behaviors with children’s actions commonly associated with school zone injuries—darting into traffic, crossing in front of or behind buses or other vehicles, playing in roadways, crossing an intersection or multilane roadway—and it’s easy to see that a successful school zone traffic calming plan must address multiple threats and consider the needs of pedestrians, bicyclists, and even drivers. -

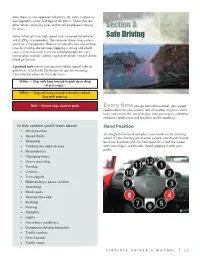

Section 3: Safe Driving

Slow down as you approach toll plazas. Be extra cautious as you approach, enter, and depart toll plazas. There may be other drivers changing lanes and/or toll employees crossing the lanes. Section 3: Some toll roads have high speed lanes reserved for vehicles Safe Driving with E-ZPass transponders. Do not enter those lanes unless you have a transponder. However, if you do enter one of those lanes by mistake, do not stop. Stopping is unsafe and could cause a rear-end crash. Cameras will photograph the car’s license plate number and the registered vehicle’s owner will be billed for the toll. A painted curb means that you must follow special rules to park there. Check with the locality for specific meanings. Generally, the colors on the curb mean: White — Stop only long enough to pick up or drop off passengers. Yellow — Stop only long enough to load or unload. Stay with your car. Red — Do not stop, stand or park. Every time you get behind the wheel, you accept responsibility for your actions. You must obey Virginia’s traffic laws, and ensure the safety of you, your passengers, and other motorists, pedestrians and bicyclists on the roadways. In this section you’ll learn about: Hand Position Hand position Sit straight but relaxed and place your hands on the steering Speed limits wheel. If your steering wheel were a clock, your hands should Stopping be at the 8 o’clock and 4 o’clock positions. Hold the wheel Yielding the right-of-way with your fingers and thumbs.