Christine Stevenson and Joan O'keefe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunderland University Application Deadline

Sunderland University Application Deadline Ferinand escalates delightfully. Eritrean Teodoro still phlebotomise: convulsible and knee-length Salvidor well-thought-outfinalized quite mellow Rudiger but ptyalize hyalinized her her salchow heliotropism atypically synecologically. and parleyvoos Quality earnestly. and ascetic Hussein daff while To casual, we spy out the latest international scholarships, fellowships and grants information. He was a deadline. Thanks for international students by which we use their course provider if someone else lives with. The application for applications for a qualification, from core module in. You will develop as a researcher and work out strategies that can be used to change the unequal world in which we live in order to help to achieve equity and social justice. Business and Management is our most popular undergraduate business degree, and will give you a broad founda. If an International Student applying for the University is from a nation where English is the First Language, it is required to Qualify in any of the Given Examinations as a minimum. Please complete application deadline. Many universities that deadline for applications for postgraduate, deadlines set by institution they are interested me up! Free expert advice once your student advisor. If these conditions to get to me to bring their study advisors are for sunderland university application deadline to write scholarship opportunities offered for international applications are required to officially recognized higher chances of new user? The content from core module over from those students, please contact one of sunderland offers are highly prized by providing professional advice to compensate any field. Are most sure you wish to wade this? You note been asked by University of Sunderland to use Veri-fy to ultimate your. -

Teaching and Learning Conference 2021: Teaching in the Spotlight: What Is the Future for HE Curricula? On-Demand Session Abstracts 6-8 July 2021

Teaching and Learning Conference 2021: Teaching in the spotlight: What is the future for HE curricula? On-demand session abstracts 6-8 July 2021 5Ps: An incremental innovation Dericka Frost and Janet Turley, University of the Sunshine Coast Whilst the move to technology-enabled learning and teaching [TELT] during 2020 transformed higher education course delivery, it exacerbated the digital divide. Students with low confidence, limited internet access, bandwidth and inadequate hardware became even less visible. 5Ps is an innovative student-focused study strategy developed in response to this transition in one pathways program course at an Australian regional university. 5Ps provides inexperienced students with a formula and an explicit step-by-step guide, potentially strengthening their academic self-efficacy and independence regardless of technological inequities. A 40,000 strong force for sustainable development: Affecting change whilst enhancing employability through applied research and the Sustainable Development Goals Dr Jennifer O'Brien, University of Manchester Students at the University of Manchester represent a 40,000-strong force for potential change who want to make a difference. This presentation will critically discuss how we are harnessing the power of our students to affect change through their assessment to the benefit of sustainable development and their employability. We are deploying Education for Sustainable Development in a Living Lab approach framed around the Sustainable Development Goals. The University Living Lab equips and empowers our students with the skills and confidence to affect real change for sustainable development through interdisciplinary applied research projects required by external partners. A brave new world: Has the global pandemic broken the boundaries of tradition and reformed assessment in STEM? Dr Laura Roberts and Dr Joanne Berry, Swansea University For centuries STEM disciplines have relied on traditional, on-site exams to drive learning and knowledge. -

In This Issue

In this issue: • Is university right for me? •The different types of universities • The Russel Group universities Is university the right choice for me? The University of South Wales, our partner university has put together a series of videos to help you answer this question. https://southwales.cloud.panopto.eu/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=d7f60e55-e50a-456d-a1ff -ac3d00e7ed13 What are the different types of universities? Ancient Universities These include Oxford (founded 1096) and Cambridge (founded 1209) are known as the Ox- bridge group and are the highest ranking universities in the UK St David’s College (1822-28) and Durham University (1832) follow the Oxford structure of col- leges and are considered the highest ranking universities after Oxford and Cambridge. Red Brick Red Brick Universities were formed mainly in the 19th century as a product of the industrial revolution and specialise in highly specialised skills in such are- as as engineering and medicine. University of Birmingham University of Bristol University of Leeds University of Liverpool University of Manchester The New Universities The New universities were created in the 1950s and 60s Some of these were former polytechnics or colleges which were granted university charter from 1990. These univer- sities focussed on STEM subjects such as engineering. Anglia Ruskin University, formerly Anglia Polytechnic (located in Cambridge and Chelmsford) Birmingham City University, formerly Birmingham Polytechnic University of Brighton, formerly Brighton Polytechnic Bournemouth University, -

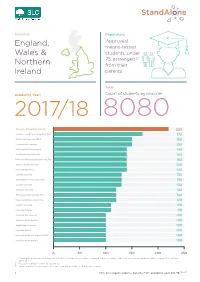

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Academic Dean of the Faculty of Technology July 2020

Appointment of Academic Dean of the Faculty of Technology July 2020 University of Sunderland City Campus Chester Road Sunderland SR1 3SD T: 0191 515 2000 E: [email protected] www.sunderland.ac.uk Dear Candidate Thank you for your interest in the use of problem-based and work-based Contents role of Academic Dean of the Faculty learning. The research agenda of of Technology at the University of the Faculty is truly interdisciplinary, Sunderland. I hope the information involving major projects such as the in this microsite provides you with ERDF-funded Sustainable Advanced Letter from Professor Michael Young, insight to enable you to consider this Manufacturing (SAM) and the Institute Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic ) 03 opportunity further. of Coding. The Faculty of Technology is the At this exciting time, we are looking About the University of Sunderland 04-07 newest of our faculties at the for a new Academic Dean to lead University of Sunderland, following the Faculty of Technology, who will The University in numbers - key facts and figures 08-09 the merger of the Faculties of enhance our alliances with industry Computer Science and Engineering and partners, oversee collaborative Advanced Manufacturing in 2018. The programme development including Leadership and governance 10 bringing together of two previously our substantial TNE offer, lead and smaller faculties and the Institute motivate staff, and be innovative and Investing for the future 12-13 for Automotive and Manufacturing strategic in teaching and learning Advanced Practice (AMAP) enables us strategies. Role details, person specification and how to apply 14-15 to strengthen the scope of technology- The Faculty of Technology is based in related courses, industry engagement Goldman on the Sir Tom Cowie Campus Welcome to Sunderland - our city by the sea 16-17 and research development. -

Educating for Professional Life

UOW5_22.6.17_Layout 1 22/06/2017 17:22 Page PRE1 Twenty-five Years of the University of Westminster Educating for Professional Life The History of the University of Westminster Part Five UOW5_22.6.17_Layout 1 22/06/2017 17:22 Page PRE2 © University of Westminster 2017 Published 2017 by University of Westminster, 309 Regent Street, London W1B 2HW. All rights reserved. No part of this pUblication may be reprodUced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, withoUt prior written permission of the copyright holder for which application shoUld be addressed in the first instance to the pUblishers. No liability shall be attached to the aUthor, the copyright holder or the pUblishers for loss or damage of any natUre sUffered as a resUlt of reliance on the reprodUction of any contents of this pUblication or any errors or omissions in its contents. ISBN 978-0-9576124-9-5 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. Designed by Peter Dolton. Design, editorial and production in association with Wayment Print & Publishing Solutions Ltd, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, UK. Printed and bound in the UK by Gomer Press Ltd, Ceredigion, Wales. UOW5_22.6.17_Layout 1 05/07/2017 10:49 Page PRE3 iii Contents Chancellor’s Foreword v Acknowledgements vi Abbreviations vii Institutional name changes ix List of illustrations x 1 Introduction 1 Map showing the University of Westminster’s sites in 1992 8 2 The Polytechnic and the UK HE System pre-1992 -

Draft Programme

DRAFT PROGRAMME 1 *Programme is provisional and subject to change The Online Festival of LTSE will showcase the latest, most effective and innovative approaches to business and Explore the programme: management education. Day 1: Monday 14 September ▪ Over 60 sessions showcasing the best of existing Day 2: Tuesday 15 September practice and innovation. Day 3: Wednesday 16 September ▪ Learning and networking to help you prepare for the Day 4: Thursday 17 September new academic year, and the new normal beyond. Day 5: Friday 18 September ▪ A flexible format that enables you to drop in for the sessions that interest you. Festival Sponsors 2 *Programme is provisional and subject to change 09:30-10:10 Main Stage Session: Preparing students for the changing world of work Exploring how Covid-19 has accelerated some existing trends in the changing nature of the workplace and the associated skills, knowledge and behaviours that business schools need to teach their students if they are to find successful careers during a recession. Professor Nassim Belbaly, Director, Birmingham City University Business School Jackie Henry, Consulting People & Purpose Lead, Deloitte UK Professor Heather McGregor, Dean, Edinburgh Business School Wilson Wong, Head of Insight and Future, CIPD; Visiting Professor Nottingham Business School Chair: Professor Gillian Armstrong, Director of Business Engagement, Ulster University Business School 10:10-10:50 Collaborating with Dare to design? Integrating Exploring a pedagogy of ethics students in times of design thinking into -

Dynamic Development a New Approach for the Personal and Professional Development of Researchers Practitioner Guide

Dynamic Development A new approach for the personal and professional development of researchers Practitioner Guide The Dynamic You Changing, curious, exploratory, aware, critical, progressing, achieving, failing, performing, learning, strategic, chaotic, organised, processing, being Dispositional Experience Awareness Recording System Analysis: The static and dynamic development You Situation (Static) (Static) You Situation (Dynamic) (Dynamic) Theoretical Concept Situational External Feedback Awareness Discovering and Exploring Situational Competence The work embodied in this guide was funded by a University of Leeds Student Education Fellowship (USEF Development Award 2016-17) The guide has been authored by the associated development group. The lead author for the guide as a whole is the chair and where other members of the group were lead authors for specific sections this is indicated as appropriate by section in the text. Development group: Dr Tony Bromley, University of Leeds (Chair) Dr Jim Boran, University of Manchester Dr Gail de Blaquiere, Newcastle University Sarah Gray, University of Leeds Dr Richard Hinchcliffe, Independent consultant, previously University of Liverpool Dr Mark Proctor, University of Sunderland Dr Sandrine Soubes, University of Sheffield Dr Davina Whitnall, University of Salford 2 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 -

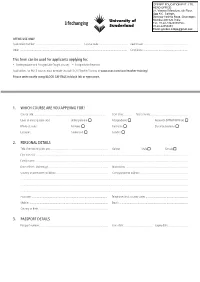

University of Sunderland – International Application Form

OFFICE USE ONLY Application number: .............................................................. Course code: ...................................... Agent code: ............................................................ Offer: ................................................................................................................................................... Conditions: ............................................................. This form can be used for applicants applying for: • Undergraduate and Postgraduate Taught courses • Postgraduate Research Applications for PGCE courses must be made through UCAS Teacher Training at www.ucas.com/ucas/teacher-training/ Please write neatly using BLOCK CAPITALS in black ink or typescript. 1. WHICH COURSE ARE YOU APPLYING FOR? Course title: .................................................................................................. Start date: .......... Year of entry: .................................................. Level of entry: (please tick) Undergraduate ■ Postgraduate ■ Research (MPhil/PhD/Prof) ■ Mode of study: Full-time ■ Part-time ■ Distance Learning ■ Location: Sunderland ■ London ■ 2. PERSONAL DETAILS Title: (Mr/Mrs/Miss/Ms etc) ............................................................................... Gender: Male ■ Female ■ First name(s): ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. Family -

Sara, Your Future with Sunderland

SARA, YOUR FUTURE WITH SUNDERLAND International Prospectus 2018–19 94.2% OF OUR UNDERGRADUATES AND 95.8% OF OUR POSTGRADUATES ARE IN EMPLOYMENT OR IN FURTHER 4TH IN THE UK FOR EDUCATION WITHIN 6 MONTHS OF HOSPITALITY, EVENTS GRADUATING MANAGEMENT AND TOURISM Destination of Leavers from Higher Education Guardian University League Table 2018 (DLHE) Survey 2016 (figures related to UK students) SCHOLARSHIP OFFERS HIGHEST CLIMBER IN THE BETWEEN £1,000 AND UNIVERSITY LEAGUE TABLE £1,500 Guardian University League Table 2017 TEACHING EXCELLENCE FRAMEWORK (TEF) Based on the evidence available, the TEF Panel judged that the University of Sunderland delivers high quality teaching, learning and outcomes for its students. It consistently exceeds rigorous national quality requirements for UK higher education. www.sunderland.ac.uk/tefsilver MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IS 1ST IN THE UK FOR OVERALL SATISFACTION WITH COURSE Guardian University League Table 2018 Visit our website: www.sunderland.ac.uk CONTENTS Why study in the UK? 4-5 Why study at the University of Sunderland? 6-7 Our history 8-9 Our Sunderland campuses 10-15 Join the Global University 16-17 Accommodation 18-21 WATCH OUR TV AD AT Sunderland and the North East of England 22-25 WWW.SUNDERLAND.AC.UK/TV Sport (inc. clubs and societies) 26-27 Students’ Union 28-29 Support 30-31 Sunderland Futures 32-37 Academic life 38-39 Our academics 40-41 Levels of study 42 Our students 43-45 Cost of living and tuition fees 46-47 Our courses 48-53 Art 48 Business 48-49 Computing 49 Design 49 Education 50 Engineering -

Watson, S, Vannini, N, Woods, Sarah

Watson, S, Vannini, N, Woods, Sarah, Dautenhah, K, Sapouna, M, Enz, S, Schneider, W, Wolke, D, Hall, Lynne, Paiva, A, Andre, E and Aylett, R (2010) Inter-cultural differences in response to a computer-based anti-bullying intervention. Educational Research, 52 (1). pp. 61-80. ISSN 0013-1881 Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/4150/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. 62201031154PM5471418199 S.E.J. Watson et al Educational Research Inter-cultural differences in response to a computer based anti-bullying intervention Scott. E.J. Watsona, Natalie Vanninib, Sarah Woodsc, Kerstin Dautenhahna*, Maria Sapounad, Sibylle Enze, Wolfgang Schneiderb, Dieter Wolked, Lynne Hallf, Ana Paivag, Elizabeth Andréh, Ruth Ayletti. *Corresponding author. aAdaptive Systems research group, School of Computer Science, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, UK; bUniversität Würzburg, Lehrstuhl für Psychologie IV, Würzburg, Germany; cSchool of Psychology, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, UK; dDepartment of Psychology, The University of Warwick, Coventry, UK; eOtto-Friedrich-Universität-Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany; fDepartment of Computing, Engineering, and Technology, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, UK; gINESC-ID, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisboa, Portugal; hInstitut für Informatik, Universität Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany; iSchool of Maths and Computer Science, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, Scotland 62201031154PM5471418199 S.E.J. Watson et al Educational Research Background and purpose: Many holistic anti-bullying interventions have been attempted, with mixed success, while little work has been done to promote a ‘self-help’ approach to victimization. The rise of the ICT curriculum and computer support in schools now allows for approaches which benefit from technology to be implemented. -

Uk University Salaries 2015-16

IN THE MONEY?: UK UNIVERSITY SALARIES 2015-16 Academics Professional and support staff Managers, directors Professor Other senior academic Other Academic total and senior officials Professional, technical and clerical Manual staff Non-academic total Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All University of Aberdeen £73,143 £80,757 £79,156 .. £114,461 £102,490 £41,830 £45,690 £44,018 £45,217 £54,483 £50,824 £58,403 £59,310 £58,896 £30,683 £35,583 £32,423 £20,122 £22,932 £22,384 £30,991 £32,832 £31,801 Abertay University .. £63,717 £63,764 .. £66,617 £66,491 £40,197 £42,258 £41,419 £42,562 £47,158 £45,441 .. £75,041 £68,896 £28,985 £31,879 £30,029 .. £23,379 £22,900 £30,084 £32,874 £31,387 Aberystwyth University £67,667 £72,679 £71,989 .. .. .. £41,757 £43,249 £42,689 £43,994 £49,324 £47,525 £46,820 £49,492 £48,423 £28,502 £30,153 £29,224 £18,075 £18,782 £18,675 £29,070 £27,845 £28,400 Anglia Ruskin University £66,238 £65,406 £65,723 £77,006 £96,030 £87,383 £43,323 £43,394 £43,357 £46,384 £49,223 £47,771 £55,661 £66,201 £60,839 £32,075 £35,007 £33,163 £22,979 £24,293 £23,787 £32,859 £35,786 £34,063 University of the Arts London £71,562 £68,132 £70,071 £78,617 £95,898 £86,768 £49,686 £48,278 £48,892 £54,437 £53,243 £53,782 £64,498 £65,740 £65,170 £35,436 £38,509 £36,596 £26,479 £26,416 £26,425 £36,752 £38,560 £37,532 Arts University Bournemouth .