Jacques Ferron's Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Research A

11 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Research A writer or an author is going to express their idea through their writing or text, such as in poem, novel. It is interesting because an author will tell it in beauty of words, phrases, sentences even passages and books. They may express about themselves, their surrounding, environment, society condition, nature, politic, history or criticism of something. According to Engels which rewritten by Laurenson and Swingewood (1972), he stated that literature as reflection of social processes. It means that literature as written language product is related to society that gives colors in the work. Basing on explanation above, it is clear that literary work is product of society. An author is not able to be separated from the society or environment, they relate each others, and it is harmony. In creating literary work, he will be influenced by surrounding, and the result of writing, literary work, is going to influence the readers as society members. According to Wellek and Warren (1948: 3), literature is “creative, an art”. In this term, they stated that literature is a creativity work in art. This term is still wide and common. Then, Cuddon (1999: 472) defines literature as “a vague term which usually denotes works which belong to the major genres: epic, drama, lyric, novel, short story ode.” Cuddon is able to give explanation clearer than Wellek and Warren, he give the types or work of it. 1 2 In several literary works express many features of thought and feeling on subjects as varied as social class, work, love, religion, nature, and art. -

Descendants of John Burnett Turner, Jr

Descendants of John Burnett Turner, Jr By Nyla Creed DePauk John Burnett Turner, Jr., was born November 26, 1847, in Patrick County, Virginia. John died April 27, 1933 in Marsh Fork District, Raleigh County, West Virginia. John was the son of John Burnett Turner, Sr., and Naomi Angeline Exoney Via who settled in Raleigh County about 1857. John, Jr., is buried at Drews Creek Hollow. The cemetery is in Canterbury Branch of Drews Creek, Raleigh County. John married first Jemima Jane Canterbury on May 28, 1868, in Raleigh County. The marriage was performed by the Reverend Andrew Workman. Jemima was the daughter of Rufus Canterbury and Susannah Dickens. She was born about 1848 in Fayette County, and died in June 1888 in Raleigh County. John married second Nancy Jackson on April 1, 1889, in Raleigh County. Nancy was the daughter of Mabane Jackson and Sarah Dew. She was born February 26, 1855, in Raleigh County, and died after 1900 in Raleigh County. John married third Mary Jane Lewis about 1906. Mary was the daughter of Charles Lewis and Martha Fleshman. She was born October 14, 1865, in Trap Hill District, Raleigh County, and died November 1, 1932, in Munitions, Marsh Fork District, Raleigh County. Children of John Turner and Jemima Canterbury are: 1. Louisa Elizabeth "Lizzie" Turner was born November 30, 1869 in Raleigh County. She married first William Jewell on March 22, 1886, in Raleigh County. He was born 1860 in Prince William County, Virginia, and died about 1889. She married second Andrew Wilson Webb on September 25, 1889, in Raleigh County. -

Thesis Recovered from Obscurity: “Structures of Feeling” and Discourses of Identity and Power Relations Through the Peripher

Thesis Recovered from Obscurity: “Structures of Feeling” and Discourses of Identity and Power Relations through the Peripheral Characters in the Novels of Charles Dickens. by Ivan Pragasan Pillay Supervisor: Dr C.A. Woeber 1 Recovered from Obscurity: “Structures of Feeling” and Discourses of Identity and Power Relations through the Peripheral Characters in the Novels of Charles Dickens Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg: 2011) This whole thesis, unless specifically indicated to the contrary in the text, is my own, original work. ____________________ Ivan Pragasan Pillay 2 I dedicate this work to Ma af 3 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the abiding grace of Jesus Christ who, as He promised, never did leave nor forsake me. And, lest I forget: My supervisor, Dr Catherine A. Woeber for selflessly going beyond the call of duty to see this work through to its conclusion. Her expertise and professionalism, in setting and maintaining the required standards at all times, has enriched me and I remain indebted to her. My dear friends, the Jogessar family: Jamesy, Rosy, Alice and Sharma who urged me on and picked me up when, at times, it seemed as though the finish was, infinitely, beyond my reach. They were my seconds throughout this, often, gruelling marathon. My son, Courtney Austin and daughter, Claire Ann for believing in me. My mother Pat, aunt Loga and the rest of my family for their unstinting love and support. My colleagues Suren Naidoo and Roy Somaru for never being too far away when it mattered most. -

Tamsin Evernden Phd July 2017

Dickens and Character: ‘The Economy of Apprehension’ Tamsin Evernden Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted to the Department of English, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy !1 Declaration of Authorship I, Tamsin Evernden, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: !2 Abstract In November 1867 a young Henry James encountered Charles Dickens at the height of his fame. James was only briefly in Dickens’s presence but noted ‘a kind of economy of apprehension’: a look in the older writer’s eye that he equated to power withheld; limiting local interaction, but also representative of the way Dickens now meted out his implicitly finite gifts, holding something in reserve. Two years previous, in 1865, James had submitted a damning review of Dickens’s last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, in which he revisited arguments that had dogged Dickens from the beginning of his career, as to how he ‘created nothing but figure’ and ‘added nothing to our understanding of human character’. Although critical opinion has developed over the ensuing century and a half, the penumbra of superficiality remains, with a focus on Dickens’s overt stylisation: melodrama, grotesquerie; pattern and repetition forming the locus of scholarship reassessing Dickens’s prose techniques. I use James’s phrase to initiate a two-way premise; one speculative: that even in Dickens’s apparently simple characterisation there was supreme elective skill winnowing out generative components, so what is outwardly manifest belies the complexity of the founding structure. -

Big Bear, Was a Cree Chief Who Was Involved, Albeit Not by Choice, in the 1885 Resistance

Mistahimaskwa (c1825-1888): Biography Mistahimaskwa, or Big Bear, was a Cree chief who was involved, albeit not by choice, in the 1885 Resistance. He is perhaps one of the most misunderstood figures in Canadian history. Little is known about his early years. He was born around 1825 near Jackfish Lake and Fort Carlton, which are now in present-day Saskatchewan. His heritage was Saulteaux through his father, Muckitoo or Black Powder, a minor chief of a mixed Cree- Saulteaux band and Plains Cree, through his mother, whose name is unknown. Although his father was Saulteaux and he could speak Saulteaux, Mistahimaskwa considered himself Cree. Mistahimaskwa was a traditional spiritual person. His Manitou spirit was the bear: in his youth he received a vision from the Bear Spirit – the Cree’s most powerful animal Manitou. His name, song, and power bundle were a result of the visitation. His power bundle consisted of a skinned-out bear’s paw with its claws intact, which was sewn onto a scarlet flannel. Mistahimaskwa believed that when he wore this power bundle around his neck nothing could harm him because the Bear Spirit’s power rested against his soul. First Nations Oral Tradition maintains that Mistahimaskwa wore this bundle during times of danger. The bundle gave him great courage. Near the end of his life he became a baptized Catholic. In his early years, Mistahimaskwa spent most of his time hunting bison. His mixed Cree-Saulteaux band traveled throughout the remaining bison hunting grounds of what are now Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Montana. In other parts of the year, his people camped in the woods of what are now north-central Alberta and Saskatchewan. -

Francis Dickens and the Jamiesons

The Jamieson Connection with the Charles Dickens Family By Betty Hagberg Late in the year of 1885, Alexander Jamieson was in Ottawa, Canada and met Francis Jeffery Dickens, son of the famous English author Charles Dickens. Captain Dickens was just completing his service with the Northwest Mounted Police. Alexander invited Francis to visit his family in Moline and consider undertaking a speaking tour of the United States. Charles Dickens and his wife Catherine had a family of 10 children. Francis Jeffrey Dickens was the fifth child and third son. He was known as Frank in the family and given the nickname “chickenstalker” by his Charles Dickens father, supposedly because he like to play hunting games as a child. None of the Dickens children really lived up to the expectations of their illustrious father, and Francis was no exception. As was the family custom he was sent to boarding school in France at the age of 7. Reportedly his father directed he be given a shot of port everyday to help build his strength. By 14 he was in Germany studying languages with the hope of going into medicine. He eventually gave up the idea of becoming a physician because of his stammer, but he did gain proficiency in both French and German. As a young man he worked in the family publication business “All Francis Jeffrey Dickens the Year Round” the weekly literary magazine owned by his father. This publication published some of Charles Dickens novels in serial form. At age 20 Francis left Britain for India, where he thought he would join his older brother Walter, only to find on arrival that Walter had died of an aneurism. -

The Edmonton Journal

Behind Canada's only mass hanging; Edmonton author crafts unconventional history of flashpoint in Northwest Rebellion Edmonton Journal Oct 25 2009 Byline: Diana Davidson The Frog Lake Reader Myrna Kostash NeWest Press 260 pp., $26.95 In the second chapter of The Frog Lake Reader, Edmonton author Myrna Kostash describes standing at a 19th-century burial site a few hours east of the city. "Shoulder-high in grass and bramble, wild rose bushes, and aspen deadfall," she writes, the "calm beauty of the fields spread out all around belied the violence and tragedy commemorated here." The tragedy and violence at Frog Lake marked the beginning of the Northwest Rebellion and is the subject of Kostash's ninth book. Most readers will know that the rebellion and its famous Métis leader, Louis Riel, emerged during a time of change, tension, and miscommunication between the federal government, new settlers, fur traders, indigenous and emerging cultures in a young country. Frustrated by a government that was not honouring their treaties, a struggling one-trade economy and a disappearing buffalo population, Cree and Métis people in the Prairies started to organize and protest in the 1880s--a rising tide punctuated by Chief Big Bear's refusal to sign Treaty Six in 1876. By 1885, relations had deteriorated and rebellions had begun. Batoche and Duck Lake are two battle sites often cited in history texts. Kostash's book brings our attention to the conflict at Frog Lake settlement, northwest of modern-day Lloydminster, over Easter 1885. Big Bear's son, Imasees, and the Cree chief Wandering Spirit led a group of men in an attack on white settlers, forcing them into the Catholic church. -

DICKENS CATALOGUE Jarndyce

THE DICKENS CATALOGUE Jarndyce CATA 218.indd 1 09/05/2016 09:59:42 Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London www.jarndyce.co.uk WC1B 3PA VAT.No.: GB 524 0890 57 CATALOGUE CCXVIII SUMMER 2016 THE DICKENS CATALOGUE Catalogue: Joshua Clayton Production: Carol Murphy & Ed Lake. All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items on this catalogue marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (20%) to customers within the EU. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. High resolution images are available for all items, on request; please email: [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £5.00 each include: Books & Pamphlets 1564-1820. Parts I & II; The Museum: Jarndyce Miscellany; Conduct & Education; Anthony Trollope, A Bicentenary Catalogue. The Romantics: A-Z, with The Romantic Background (four catalogues); JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; European Literature in Translation; Books & Pamphlets: 1600-1800; English Language; 19th Century Novels. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. Valuations for insurance or probate can be undertaken anywhere, by arrangement. A SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE is available for Jarndyce Catalogues for those who do not regularly purchase. Please send £20.00 (£30.00 / U.S.$55.00 overseas, airmail) for four issues, specifying the catalogues you would like to receive. -

Pritchard Articles Informant's Address

DOCUMENT NAME/INFORMANT: PRITCHARD ARTICLES INFORMANT'S ADDRESS: 505 AVENUE F SOUTH SASKATOON, SASKATCHEWAN INTERVIEW LOCATION: 505 AVENUE F SOUTH SASKATOON, SASKATCHEWAN TRIBE/NATION: METIS LANGUAGE: ENGLISH DATE OF INTERVIEW: INTERVIEWER: INTERPRETER: TRANSCRIBER: HEATHER YAWORSKI SOURCE: SASKATOON NATIVE WOMEN'S ASSOC. & BATOCHE CENTENARY CORP. TAPE NUMBER: #IH-SD.50A DISK: TRANSCRIPT DISC #159 PAGES: 14 RESTRICTIONS: THIS MATERIAL IS THE PROPERTY OF THE GABRIEL DUMONT INSTITUTE OF NATIVE STUDIES, AND SHALL BE AVAILABLE FOR LISTENING, REPRODUCTION, QUOTATION, CITATION AND ALL OTHER RESEARCH PURPOSES, INCLUDING BROADCASTING RIGHTS WHERE APPLICABLE, IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REGULATIONS WHICH MAY HAVE BEEN OR WHICH MAY BE ESTABLISHED BY THE GABRIEL DUMONT INSTITUTE OF NATIVE STUDIES OR ITS SUCCESSORS FOR THE USE OF MATERIALS IN ITS POSSESSION: SUBJECT, HOWEVER TO SUCH RESTRICTIONS AS MAY BE SPECIFIED BELOW. ARTICLES: IN MEMORY OF MARY ROSE (PRITCHARD) SAYERS THE LAST WITNESS In the early morning of April 2, 1885, Wandering Spirit and his Indian brothers perpetrated the Frog Lake massacre. Eighty-five years later on the morning of December 27, 1970, the last witness to that frightful event passed away. Mrs. Joseph Sayers nee Mary Rose Pritchard was born at Rocky Mountain House on February 12, 1874. Her parents were John Pritchard and Rose Delorme. At the time of the massacre her father was working as an interpreter for the Indian Agent at Frog Lake and Mary Rose, then only eleven years old, was in her father's house with four brothers and three sisters. Mary Rose saw it happen right in front of her home.1 There Wandering Spirit shot down Thomas Quinn, the Indian Agent. -

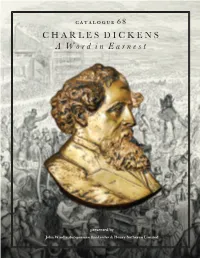

C H a R L E S D I C K E N S a W O R D I N E a R N E

C A T A L O G U E 6 8 C H A R L E S D I C K E N S A W o r d i n E a r n e s t presented by John Windle Antiquarian Bookseller & Henry Sotheran Limited r “Electric communication will never be a substitute for the face of someone who with their soul encourages another person to be brave and true.” - Charles Dickens “I have nothing else to tell; unless, indeed, I were to confess that no one can ever believe this narrative, in the reading, more than I have believed it in the writing.” - Charles Dickens “God bless us, every one!” -Charles Dickens C A T A L O G U E 6 8 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R & H E N R Y S O T H E R A N L I M I T E D 2018 C A T A L O G U E 6 8 Charles Dickens A Word in Earnest presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R & H E N R Y S O T H E R A N L I M I T E D 2018 J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233, San Francisco, California 94108 www.johnwindle.com [email protected] (415) 986-5826 H E N R Y S O T H E R A N L T D. -

CATA 201.Ppp

_____________________________________________________________ Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 - 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 - 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London WC1B 3PA V.A.T. No. GB 524 0890 57 _____________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE CCI WINTER 2012-13 DICKENS & HIS CIRCLE Catalogue: Joshua Clayton Production: Carol Murphy All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items on this catalogue marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (current rate 20%) to customers within the EU. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. Email address for this catalogue is [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £5.00 each include: Cataloge 200: A Miscellany; Books & Pamphlets 1583-1826; Women I: Books for & about Women; Women II-IV: Women Writers A-Z; The Dickens Catalogue; The Library of a Dickensian (£20); Social Science, Part I: Politics & Philosophy, and Part II: Economics & Social History; The Social History of London: inluding poverty & Public Health; Street Literature: I Broadside, Slipsongs & Ballads; II Chapbooks & Tracts. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: Street Literature: III Songsters, Lottery Puffs, Street Literature Works of Reference; Language, Conduct & Education; The Romantics. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. Valuations for insurance or probate can be undertaken anywhere, by arrangement. A SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE is available for Jarndyce Catalogues for those who do not regularly purchase. -

Dickens: Irish Friends and Family Ties

Dickens: Irish Friends and Family Ties Litvack, L. (Author). (2012). Dickens: Irish Friends and Family Ties: An Exhibition at the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland to celebrate the Charles Dickens bicentenary, in association with the Dickens 2012 NI Festival . Exhibition, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:04. Oct. 2021 Dickens: Irish Friends & Family Ties INTRODUCTION TIMELINE FAMILY TREE LETTERS Charles Dickens Dickens was a well known and loved figure in 1812 - Born 7 February, in Portsmouth John Elizabeth George Georgina Letters form an important source Dickens Barrow Hogarth Thompson (1812-1870) Ireland. He visited three times on reading tour of information about the public 1821 - Starts School married 1809 married 1809 (in 1858, 1867, and 1869) and spoke warmly and private lives of the Victorians.