Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historical Thar Desert of India

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 12 No 4 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) www.richtmann.org July 2021 . Research Article © 2021 Manisha Choudhary. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Received: 14 May 2021 / Accepted: 28 June 2021 / Published: 8 July 2021 The Historical Thar Desert of India Manisha Choudhary Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Delhi, India DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss-2021-0029 Abstract Desert was a ‘no-go area’ and the interactions with it were only to curb and contain the rebelling forces. This article is an attempt to understand the contours and history of Thar Desert of Rajasthan and to explore the features that have kept the various desert states (Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Barmer, Bikaner etc.) and their populace sustaining in this region throughout the ages, even when this region had scarce water resources and intense desert with huge and extensive dunes. Through political control the dynasts kept the social organisation intact which ensured regular incomes for their respective dynasties. Through the participation of various social actors this dry and hot desert evolved as a massive trade emporium. The intense trade activities of Thar Desert kept the imperial centres intact in this agriculturally devoid zone. In the harsh environmental conditions, limited means, resources and the objects, the settlers of this desert were able to create a huge economy that sustained effectively. The economy build by them not only allowed the foundation and formation of the states, it also ensured their continuation and expansion over the centuries. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Report of a Tour in Eastern Rajputana in 1871-72 and 1872-73

c^^‘£lt^0^agic^^;l gurbeg of Inbm. EEPORT OF A TOUR m EASTERN RAJPUTANA ' • IN 1871-72 AND 1872-7 3. jcOMPlIME^TARri BY A. C. L. CAELLEYLE, ABSISTAKT, AECHHOMSICAI. SUKVEr, S. BNDEE THE SUPERINTENDENCE OF MAJOE-aENEEAL A. GUEEIEGHAAI, O.S.I.', C.I.E., PIEECTOE-GENEEAI> AEOH^OLOGIOAE BUEVEl’, VOLUME VI. •‘What is aimed at is an aocnrate description, illustrated by plans, measurements, drawines or photographs, and by copies of insorlptiona, of such remains as most deserve notice, with the history of them so far as it may be trace- able, and a record of the traditions that are preserved regarding them,"—Lonn CANirmo. "What the learned rvorid demand of ns in India is to be quite certain of onr dafa, to place tho mounmcntol record before them exactly as it now exists, and to interpret it faithfully and literally.'*—Jambs Pbiksep. Sengal AsCaiic Soeieig'i JaurnaJ, 1838, p. 227. CALCUTTA: OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING. 1878. CONTENTS OE VOLUME VI. PAGE. 1. Mountain Eangea of Eajputana 1 2 Achnera 5 3. ]Ihera 13 4^Eupbas 16 5. Jagnei' ..... 24 Satmas v/ .... _33 Baiana V . • . 40 ' Santipur, or Tijayaraandargarh. 64 9. Sikandra .... 74 10. MacLMi, or SanckMd 77 Baiiat 91 12. Deosa ..... 104 13. Nain, or Nai .... 109 . 14 Cliatsu . ^ .... 116 . 15. Shivdungr .... 12l' 16. Thoda, or There 124 17. Bagliera or Yyaghra — — 136 18 Vigalpirs- < . 152 19. Dhaud, or Ghar 160 20. Nagar, or Karkota Nagara 162 21. ITagari, or Tambavati Nagari . 196 22. Mora ..... 227 23. Bijoli 234 PLATES. I. Map of Eastern Eajputana, II. -

Origin of the Rajputs : ______

ORIGIN OF THE RAJPUTS : __________________________ There is no agreement among the scholars regarding the origin of the Rajputs. It has been opined by many scholars that the Rajputs are the descendants of foreign invaders like Sakas, Kushana, white- Hunas etc. All these foreigners, who permanently settled in India, were absorbed within the Hindu society and were accorded the status of the Kshatriyas. It was only afterwards that they claimed their lineage from the ancient Kshatriya families. The other view is that the Rajputs are the descendants of the ancient Brahamana or Kshatriya families and it is only because of certain circumstances that they have been called the Rajputs. Earliest and much debated opinion concerning the origin of the Rajputs is that all Rajput families were the descendants of the Gurjaras and the Gurjaras were of foreign origin. Therefore, all Rajput families were of foreign origin and only, later on, were placed among Indian Kshatriyas and were called the Rajputs. The adherents of this view argue that we find references to the Guijaras only after the 6th century when foreigners had penetrated in India. So, they were not of Indian origin but foreigners. Cunningham described them as the descendants of the Kushanas. A.M.T. Jackson described that one race called Khajara lived in Arminia in the 4th century. When the Hunas attacked India, Khajaras also entered India and both of them settled themselves here by the beginning of the 6th century. These Khajaras were called Gurjaras by the Indians. Kalhana has narrated the events of the reign of Gurjara king, Alkhana who ruled in Punjab in the 9th century. -

The Cultural Heritage of North India

Mughals, Rajputs & Villages: The Cultural Heritage of North India 4 FEB – 25 FEB 2020 Code: 22001 Tour Leaders Em. Prof. Bernard Hoffert Physical Ratings Prof. Bernard Hoffert leads this tour visiting three magnificent capitals of the Mughal Empire – Delhi, Agra & Fatehpur Sikri – and a number of great Rajput fortress cities of Rajasthan. Overview Tour Highlights Professor Bernard Hoffert, former World President of the International Association of Art-UNESCO (1992-95), leads this cultural tour of North India. Visit three magnificent princely capitals in the heartland of the Mughal Empire – Delhi, Agra and Fatehpur Sikri – and a number of great Rajput fortress cities of Rajasthan. Explore the fusion of Indian and Islamic cultures at Mughal monuments, such as Agra's Red Fort, Shah Jahan's exquisite Taj Mahal, and Akbar the Great's crowning architectural legacy, Fatehpur Sikri – all of which are UNESCO World Heritage sites. The opulence and grandeur of Mughal architecture is also experienced at a number of matchless Rajput palaces. Stay in former palaces that are now heritage hotels – an experience which enhances our appreciation of this sumptuous world. Visit great Hindu and Jain temples, encounter the vernacular architecture of Rajasthan, including its famous stepped wells and villages, and explore fortresses like Jaisalmer and Bikaner that rise from the Thar Desert in the state's north. Explore the vibrant folk culture of Rajasthan, manifest in its fine music, dance and textiles. Experience a boat cruise on Lake Pichola at Udaipur, a 4WD drive excursion to view blackbuck (an endangered species of antelope native to the Indian subcontinent) and an elephant ride in Jaipur. -

57C42f93a2aaa-1295988-Sample.Pdf

Notion Press Old No. 38, New No. 6 McNichols Road, Chetpet Chennai - 600 031 First Published by Notion Press 2016 Copyright © Pratap Singh Mehta 2016 All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-93-5206-600-1 This book has been published in good faith that the work of the author is original. All efforts have been taken to make the material error-free. However, the author and the publisher disclaim the responsibility. No part of this book may be used, reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The information regarding genealogy of Deora Chauhans and Bachhawat Mehtas, available from different books of history, internet, “Bhaats” (story tellers) and inscriptions, is full of contradictions and the names are at variance. The history of any person or place is also the perception and objective of the writer. However, care has been taken to present the paper factually and truly after due moderation. Therefore, the author and publisher of this book are not responsible for any objections or contradictions raised. Cover Credits: Painting of Mehta Rai Pannalal: Raja Ravi Varma (Travancore), 1901 Custodian of Painting: Ashok Mehta (New Delhi) Photo credit: Ravi Dhingra (New Delhi) Contents Foreword xi Preface xiii Acknowledgements xvii Introduction xix 1.1 Genealogy of Songara and Deora Chauhans in Mewar 4 1.2 History – Temple Town of Delwara (Mewar) 7 Chapter 1.3 Rulers of Delwara 10 12th–15th 1.4 Raja Bohitya Inspired by Jain Philosophy 11 Century -

Tod's Annals of Rajasthan; the Annals of the Mewar

* , (f\Q^A Photo by] [Donald Macbeth, London MAHARANA BHIM SINGH. Frontispiece TOD'S ANNALS OF RAJASTHAN THE ANNALS OF MEWAR ABRIDGED AND EDITED BY C. H. PAYNE, M.A. LATE OF THE BHOPAL STATE SERVICE With 16 full page Plates and a Map NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND CO. London : GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS, LIMITED Preface "Wherever I go, whatever days I may number, nor time nor place can ever weaken, much less obliterate, the memory of the valley of Udaipiir." Such are the words with which Colonel James Tod closed his great work, the Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan. Few men have ever known an eastern race as Tod knew the Rajputs. He not only knew them through and through, their manners, their their ideals traditions, their character, and ; but so great was his admiration for their many noble qualities, and so completely did he identify himself with their interests, that by the time he left India he had almost become a Rajput himself. The history of Rajputana was, therefore, a subject very to Tod's heart both dear ; and, possessing imagina- tion and descriptive power, he was able to infuse into his pages much of the charm of a romance, and, what is still more rarely to be found in historical works, a powerful human interest. His sympathy for the is in line he wrote Rajputs apparent every ; but if his enthusiasm leads him at times to over- estimate their virtues, he never seeks to palliate their faults, to which, in the main, he attributes the ruin which overtook their race. -

Huna Origin of Gurjara Clans डा

डा. सशु ील भाटी Huna origin of Gurjara Clans (Key words- Gurjara, Huna, Varaha, Mihira, Alkhana, Gadhiya coin, Sassnian Fire altar) Many renowned historian like A. M. T. Jackson, Buhler, Hornle, V. A. Smith and William crook Consider the Gurjaras to be of Huna stock. The way in which inscriptions and literature records frequently bracket Gurjaras with the Hunas suggests that the two races were closely connected. There are evidences that the Gurjaras were originally a horde of pastoral nomads from the Central Asia whose many clans have Huna origin. Numismatic Evidences- Coins issued by Hunas and Gurjaras have remarkable similarity. In a way coins issued by Gurjaras are continuation of Huna coinage. Coins issued by Hunas and Gurjaras are characterized by motif of ‘Iranian fire altar with attendants’ and are copies of coins issued by Iranian emperors of Sassanian dyanasty. The inferences of Huna’s connection with Gurjaras is strongly supported by numismatic evidences. V. A. Smith has presented these evidences in his paper “The Gurjaras of Rajputana and Kannauj’ in these words, “The barbaric chieftains who led the greedy hordes known by the generic name of Huna to the plunder of the rich Indian plains did not trouble to invent artistic coin dies, and were content to issue rude imitations of the coinage of the various countries subdued. After the defeat of the Persian king Firoz in 484 A.D., the Huns chiefly used degraded copies of the Sassanian coinage, and in India emitted extensive series of coins obviously modelled on the Sassanian type, and consequently classified by numismatists as Indo-Sassanian. -

Bikaner Travel Guide - Page 1

Bikaner Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/bikaner page 1 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, umbrella. When To Max: Min: 28.5°C Rain: Bikaner 32.79999923 91.0999984741211 706055°C mm A majestic city of forts and royal Aug palaces, Bikaner is a famous VISIT Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, destination in Rajasthan well umbrella. http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-bikaner-lp-1159358 Max: Min: Rain: known for its vibrancy and rich 31.70000076 27.39999961 82.5999984741211 culture all across the globe. There 2939453°C 8530273°C mm Jan are several great places to visit in Famous For : City Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Sep Bikaner like Junagarh Fort, The Max: Min: Rain: Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. Bikaner, 14.30000019 8.100000381 5.69999980926513 Max: Min: Rain: National Research Centre on 0734863°C 469727°C 7mm 30.70000076 25.89999961 40.7999992370605 Camel, Karni Mata Temple, Gajner a royal city in Rajasthan has almost every 2939453°C 8530273°C 5mm Feb thing to attract tourists. The sweets and Palace, Lallgarh Palace, Jain Temple Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Oct snacks of the city are well known for its Bhandasar and Kodamdesar Max: Min: Rain: Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. delicious taste. The city was founded by an 17.20000076 11.89999961 7.80000019073486 Max: Min: Rain: Temple. 2939453°C 8530273°C 3mm 27.70000076 20.79999923 10.1000003814697 audacious Rathore prince Rao Bikaji in 1486. 2939453°C 7060547°C 27mm Retaining the glory of the olden times all Mar Nov across the amplitude, Bikaner portrays a Cold weather. -

Administrative Report, Part IV, Rajputana

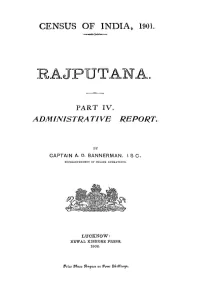

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1901. RAJPUrrANA. PART IV. ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT. BY CAPTAIN A· D. BANNERMAN, I· S. C·, SUPERINTENDENT OF CENSUS OPERATIONS. LUCKNOW: NEWAL KISHORE PRESS. 1902. SLIPS USED !N THE ABSTRACTION OF THE CENSUS SCHEDULES (I/tde IntrodLlct;'on P II/. ) Musa/mO' I?S Ja/ns AllIm ;:S·ts. Chrisftal7s andOtlt~ Marrt'ed o D D Unmarrted o o D D J Fpmales Unmarned () WIdowed " r a W!1 fI it'/h/), Guv! f'bofOZf n co. Off/ce, f>oona 1902. TABLE OP CONTENTS· CHA1?Tl;TI~ I· PRELIMINARY REMARKS. PARA, :fAGE. 1. Preliminary remarks ... 1 2. 1'be enumeration scheaule 1 3. Household scbedule 1 4. Privltte sched ule ... 1 5. Vernacular translations of enumeration book 1 6. Visit of the Census Oommissioner 2 7. Manual of instructions 3 8. Procedure for the census of military cantonments and ra,Uway Jlremis~f!. ... 3 9, Censlls of detached districts ' ..• ... 3 10. Appointment of Censu!) Superintendent, fo,1;' Rajl,lutana 4 PRELIMINARY ARRANGEMENTS. 11-12. Preliminary arrangements 4 13. Administrative units which formed charges and classes from which tbe enumerating staff was drawn 5-9 14. House.numbering 9 15. House lists 9 16. Block lists 9 17. Circle lists 10 18. En umeration books 10 19. Instruction of enumerators ... 10 PRINTING AND SUPJ;>:YY OF SCn.EDULES. 20. Printing and supply of schedules ... 10-11 CHAPTE~ ~~. THE ENUMERATION. 21. The enumeration 12 22. Preliminary record 12 23. Final census 12 24. Accuracy of the census 13 25. Demeanour of the people .••• 13 26. Provisional totals ... 13-1.4 27. -

Birds & Culture on the Maharajas' Express

INDIA: BIRDS & CULTURE ON THE MAHARAJAS’ EXPRESS FEBRUARY 10–26, 2021 KANHA NATIONAL PARK PRE-TRIP FEBRUARY 5–11, 2021 KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION FEBRUARY 26–MARCH 3, 2021 ©2020 Taj Mahal © Shutterstock Birds & Culture on the Maharajas’ Express, Page 2 There is something indefinable about India which makes westerners who have been there yearn to return. Perhaps it is the vastness of the country and its timeless quality. Perhaps it is the strange mixture of a multiplicity of peoples and cultures which strikes a hidden chord in us, for whom this land seems so alien and yet so fascinating. Or perhaps it is the way that humans and nature are so closely linked, co-existing in a way that seems highly improbable. There are some places in a lifetime that simply must be visited, and India is one of them. Through the years we have developed an expertise on India train journeys. It all started in 2001 when VENT inaugurated its fabulous Palace on Wheels tour. Subsequent train trips in different parts of the country were equally successful. In 2019, VENT debuted a fabulous new India train tour aboard the beautiful Maharajas’ Express. Based on the great success of this trip we will operate this special departure again in 2021! Across a broad swath of west-central India, we will travel in comfort while visiting the great princely cities of Rajasthan state: Udaipur, Jodhpur, and Jaipur; a host of wonderful national parks and preserves; and cultural wonders. Traveling in such style, in a way rarely experienced by modern-day travelers, will take us back in time and into the heart of Rajput country. -

The Western Railway

April 18, 1953 ACC at the Centenary Exhibition The Western Railway EATURING a reinforced con crete arch bridge motif, the HE Western Railway, which F according to the then policy of rais design of the ACC stall provides a came into being on the 5th T ing of foreign capital under a system splendid example of the versatility November, 1951, consists of the old of guaranteed return. In fifty years of concrete as a building material. B B & C I Railway (small metre of development, the present shape The daring cantilever projections gauge lengths of which were subse and extent of the Broad Gauge por and the pierced concrete panelling quently transferred to the Northern tion of the Western Railway came are outstanding among the novel and North-Eastern Railways), the into being. A still later develop features of the stall. Saurashtra, Jaipur and Rajasthan ment of the Broad Gauge line was (Udaipur) Railways, the 16-mile the electrification of the Bombay The valuable contribution made section Marwar Junction to Phulad Suburban Section of about 40 route by the Cement Industry in the de of the Jodhpur Railway, and the miles. velopment of our Railway system is Narrow Gauge Cutch State line The Metre Gauge portion of the vividly depicted through a series of (72 miles), together with the re Western Railway had its beginning photographic panels showing the cently constructed and opened in the 7o's when the section Delhi- various uses of cement for railway Deesa-Gandhidham Section con Rewari, including Farukhanagar structures ranging from large span necting with the projected port of Salt Branch, was constructed, which bridges, city terminal stations to Kandla in Cutch.