Taphonomic Resolution and Hominin Subsistence Behaviour in the Lower Palaeolithic: Differing Data Scales and Interpretive Frameworks at Boxgrove and Swanscombe (UK)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement to Agenda Agenda Supplement for Cabinet, 04/10

Public Document Pack JOHN WARD East Pallant House Head of Finance and Governance Services 1 East Pallant Chichester Contact: Graham Thrussell on 01243 534653 West Sussex Email: [email protected] PO19 1TY Tel: 01243 785166 www.chichester.gov.uk A meeting of Cabinet will be held in Committee Room 1 at East Pallant House Chichester on Tuesday 4 October 2016 at 09:30 MEMBERS: Mr A Dignum (Chairman), Mrs E Lintill (Vice-Chairman), Mr R Barrow, Mr B Finch, Mrs P Hardwick, Mrs G Keegan and Mrs S Taylor SUPPLEMENT TO THE AGENDA 9 Review of Character Appraisal and Management Proposals for Selsey Conservations Area and Implementation of Associated Recommendations Including Designation of a New Conservation Area in East Selsey to be Named Old Selsey (pages 1 to 12) In section 14 of the report for this agenda item lists three background papers: (1) Former Executive Board Report on Conservation Areas: Current Progress on Character Appraisals, Article 4 Directions and programme for future work - 8 September 2009 (in the public domain). (2) Representation form Selsey Town Council asking Chichester District Council to de-designate the Selsey conservation area (3) Selsey Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Proposals January 2007 (in the public domain). These papers are available to view as follows: (1) is attached herewith (2) has been published as part of the agenda papers for this meeting (3) is available on Chichester District Council’s website via this link: http://www.chichester.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5298&p=0 http://www.chichester.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5299&p=0 Agenda Item 9 Agenda Item no: 8 Chichester District Council Executive Board Tuesday 8th September 2009 Conservation Areas: Current Progress on Character Appraisals, Article 4 Directions and programme for future work 1. -

The Horse Butchery Site: a High-Resolution Record of Lower Palaeolithic Hominin Behaviour at Boxgrove, Uk by (Eds) M I Pope, S a Parfitt and M B Roberts

The Prehistoric Society Book Reviews THE HORSE BUTCHERY SITE: A HIGH-RESOLUTION RECORD OF LOWER PALAEOLITHIC HOMININ BEHAVIOUR AT BOXGROVE, UK BY (EDS) M I POPE, S A PARFITT AND M B ROBERTS SpoilHeap Publications, University College London, 2020. 157pp, 162 figures (of which 92 photographic plates), and 18 tables, pb, ISBN 978-1-912331-15-4, £25.00 The Boxgrove project burst into vibrant life in the early 1980s, challenging and antagonising the academic archaeological establishment in equal measure, its student leader inspired by, and part of, the contemporary punk milieu and its assault on the wider establishment. I don’t recall corduroys, but there were definitely bovver boots and braces as the shaven-headed Mark Roberts held forth in packed lecture halls, providing overwhelming proof that the history of Britain’s earliest human occupation needed substantial revision, and revealing the remarkable details of the substantial landscape of early Palaeolithic occupation preserved at the Boxgrove quarry complex; it was London (Institute of Archaeology) calling. However it wasn’t just the style, it was also the substance. Boxgrove overturned everything. Here was irrefutable evidence of human presence in Britain before the Anglian glaciation, 500,000 years ago in the interglacial period MIS 13; and not just a few suitably-crude lithic implements, but a prolific industry of large, symmetric and aesthetic ovate handaxes with sophisticated features such as tranchet sharpening. And, beyond the technical details of dating and typology, the behavioural evidence from the Boxgrove landscape challenged widely-held views that these early hominins were simpletons living in a mental world with a 15-minute time-depth, responding expediently to the appearance of a carcass or an injured animal, desperately casting around for a rock to chip, or hurl. -

WOODLAND GROVE BOXGROVE, WEST SUSSEX Goodwood Racecourse

WOODLAND GROVE BOXGROVE, WEST SUSSEX Goodwood Racecourse The South Downs Eartham East Lavant Funtington Goodwood WOODLAND GROVE Goodwood Circuit Boxgrove Hambrook Fontwell Southbourne Oving Fishbourne Chichester Bosham Barnham Donnington Chichester harbour Chichester Marina Itchenor Birdham Aldwick Bognor Regis West Wittering Sidlesham Pagham Bracklesham Bay WOODLAND GROVE BOXGROVE, WEST SUSSEX A DEVELOPMENT BY AGENTS www.domusea.com Chichester Office The Old Coach House, 14 West Pallant, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 1TB Tel +44 (0)1243 523723 www.todanstee.com The local area CITY COAST COUNTRYSIDE Chichester is one of the most sought after locations in the Less than 10 miles away is West Wittering, one of the UK’s Chichester is moments away from the rolling hills of South south it’s easy to see why. Chichester’s cathedral city is most striking unspoilt beaches and winner of a European Blue Downs National Park a recognised area of outstanding famous for its historical Roman and Anglo-Saxon heritage. Flag Award with views of Chichester harbour and the South beauty. The South Downs are popular for walking, horse riding Now, it’s the centre of culture and beauty with impressive Downs. West Wittering is a popular location for all the family and cycling, as well as simply enjoying the beautiful views. old buildings, a canal, two art galleries and renowned and also a favourite spot for kite surfers. The whole area is For the more adventurous, activities include paragliding, festival theatre. internationally recognised for its wildlife, birds and unique hang-gliding, golf, zorbing, mountain-boarding and a range of Chichester’s cosmopolitan feel brought to life by the city’s beauty. -

No. Organisation Car Name Drag Slalom Chicane Pit Stop Sprint

No. Organisation Car Name Drag Slalom Chicane Pit Stop Sprint Portfolio Additional Total Additional Award Rank 1 8th North Staffs Boys Brigade BB2 13 15 24 78 0 130 26 2 8th North Staffs Boys Brigade BB1 38 52 7 54 0 151 35 3 Arundel C of E Primary School ACE MIKE 47 17 53 63 0 180 49 4 Arundel C of E Primary School ACE TIM 64 42 60 32 -5 193 56 5 Beachborough School Merry Mary 56 22 25 15 -5 -3 110 Spirit 16 6 Beachborough School Arty Abby 4 3 2 35 -3 0 41 3 7 Bishop's Waltham Junior School BWJS 2 75 13 67 12 0 167 43 8 Bishop's Waltham Junior School BWJS 1 52 55 43 13 0 163 39 9 Blackwell Primary School Blackwell Bulldog 16 31 18 52 -5 112 17 10 Boxgrove CofE Primary School Boxgrove CofE 30 68 75 68 -5 236 73 11 Bursley Academy Goblin 3 2 4 4 78 -2 -5 81 8 12 Bursley Academy Goblin 2 8 7 41 78 -5 129 25 14 Bursley Academy Goblin 1 4 5 6 78 -5 88 10 15 Camelsdale Primary Camelsdale B 52 21 70 24 0 167 43 16 Camelsdale Primary Camelsdale A 35 5 72 51 0 163 39 17 Chesswood Junior School Chesswood Challenger 68 10 64 29 -5 166 42 18 Chesswood Junior School Will Power 84 28 63 26 -5 196 60 19 Ditcham Park School The Ditcham Dragon 26 13 50 37 0 126 24 20 droxford junior school The Drox 64 16 45 23 0 148 32 21 EASEBOURNE C.E. -

DISCOVERING SUSSEX Hard Copy £2

hard copy DISCOVERING SUSSEX £2 SUMMER 2020 WELCOME These walks are fully guided by experienced leaders who have a great love and knowledge of the Sussex countryside. There is no ‘club’ or membership and they are freely open to everyone. The walks take place whatever the weather, but may be shortened by the leader in view of conditions on the day. There is no need to book. Simply turn up in good time and enjoy. The time in the programme is when the walk starts - not the time you should think about getting your boots on. There is no fixed charge for any of the local walks, but you may like to contribute £1 to the leader’s costs - which will always be gratefully received ! If you’re not sure about any of the details in this programme please feel free to contact the appropriate leader a few days in advance. Grid References (GR.) identify the start point to within 100m. If you’re not sure how it works log on to:- http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/docs/support/guide-to-nationalgrid.pdf Public transport Dogs on Gets a Accompanied to start point lead welcome bit hilly children welcome Toilets on Bring a Bring a Pub en-route the walk snack picnic lunch or at finish TAKE CARE Listen to the leader’s advice at the start of the walk. Stay between the leader and the back-marker. If you are going to leave the walk for any reason tell someone. Take care when crossing roads – do not simply follow the person in front of you. -

![Directory. Wittering. [Sussex.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0903/directory-wittering-sussex-670903.webp)

Directory. Wittering. [Sussex.]

DIRECTORY. 968-969 WITTERING. [SUSSEX.] Norman William, 'Dorset Arms,' Pratt J.\tloses, shopkeeper, Lye green Taylor Francis, draper, grocer &. post brewer & fly proprietor Richardson Daniel, fdrmer office Patchmg Thomas, fa.rmer, Alksford frm Richardwn Thos. miller, Black ham mill Turner Thomas, shopkeeper Payne Willi.:m, farmer, Willards farm Streatfield John, farmer, Toll farm Wallis Joseph, shopkeeper Pratt David, farmer Streatfield Thomas, carrier Wells George, farmer, Coarsley farm PosT 0FFICE.-FrancisTay1or, po5ltmaster. Money orders CARRIERS TO:- are granted & paid at this office. Letters arrive by mail LONDON-Thomas Streatfield's van, every wedne3day Cdrt, from Tunbridge Wells, every morn. at ~ past 5; moru. to the Na~'s Head inn, Borough, returning from delivered at 7 a.m.; dispatched at 7 p.m thence every friday night. Hobert Jarvis'" van, from Commercial inn, the Doroet Arms, William Norman Crowborough & Hartfield, every tuesday & thursday, to PARISH SCHOOLS:- Queen's Head inn, Borough, returning from thence every St. Michael's, Thomas Rickard, master; Miss Sarah thursday & saturday Rickard, mistress TUNBRIDGB WELLs-George Gilham's cart, from East St. John's, Richd.l\fartin3 master; Mrs. Ann Martin, mstrs Grinstead, every tues. thurs. &. sat.; returning same days EAST and WEST W:ETTER.XNG. by Chichester harbour, and on the south by the British EAST WITTERING is a parish in Manhood Hundred, rape channel. Its area is 2,500 acres; the soil is of rich of Chiche~ter, West Hampnett Union, West Sussex, 7l quality. The village, which is small, is in the south miles south-west from Chicheste1·, adjoining the parishes we~tern part of the parish, 8 miles south-west from Chi of Earnley, Birdham and West \Yittering. -

Report Template

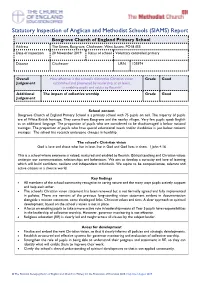

Statutory Inspection of Anglican and Methodist Schools (SIAMS) Report Boxgrove Church of England Primary School Address The Street, Boxgrove, Chichester, West Sussex, PO18 0EE Date of inspection 20 November 2019 Status of school Voluntary controlled primary Diocese Chichester URN 125974 Overall How effective is the school’s distinctive Christian vision, Grade Good Judgement established and promoted by leadership at all levels, in enabling pupils and adults to flourish? Additional The impact of collective worship Grade Good Judgement School context Boxgrove Church of England Primary School is a primary school with 75 pupils on roll. The majority of pupils are of White British heritage. They come from Boxgrove and the nearby villages. Very few pupils speak English as an additional language. The proportion of pupils who are considered to be disadvantaged is below national averages. The proportion of pupils who have special educational needs and/or disabilities is just below national averages. The school has recently undergone changes in headship. The school’s Christian vision God is love and those who live in love, live in God and God lives in them. I John 4.16 This is a school where everyone is valued, nurtured and enabled to flourish. Biblical teaching and Christian values underpin our communication, relationships and behaviours. We aim to develop a curiosity and love of learning which will build confident, resilient and independent individuals. We aspire to be compassionate, tolerant and active citizens in a diverse world. Key findings • All members of the school community recognise its caring nature and the many ways pupils actively support and help each other. -

Land at Decoy Farm House Oving, Chichester West Sussex

Land at Decoy Farm House Oving, Chichester West Sussex Archaeological Watching Brief For Oskomera Solar Power Solutions UK Ltd CA Project: 770037 CA Report: 14005 November 2015 Land at Decoy Farm House Oving, Chichester West Sussex Archaeological Watching Brief CA Project: 770037 CA Report: 14005 Accession No.: CHCDM 2015.10 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by A 06.02.15 A. Howard J. Internal General Edit REG Sulikowska review B 16.11.15 A. Howard R .Greatorex DRAFT Draft copy to REG client and CDC This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology Land at Decoy FarmHouse, Oving, Chichester: Archaeological Watching Brief CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 3 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 3 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 4 4. METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. -

MINUTES of a MEETING of the SIDLESHAM COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION HELD at SAXONS, on THURSDAY 5Th DECEMBER at 3.00P.M

MINUTES OF A MEETING OF THE SIDLESHAM COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION HELD AT SAXONS, ON THURSDAY 5th DECEMBER AT 3.00P.M. 1. Apologies for absence. Una Pearce 2. Approval and signing of the minutes of the previous meeting held on 28th October. 3. Matters arising not on the agenda. There were none. 4. Emergency Plan follow up. D.P. reported she had spoken to Mike Allisstone about handing over the nearly finish plan he and D.P. had compiled, and he was happy to do so. D.P. to circulate or distribute paper copies. David C.J. will ask Bill Martin if the Association may put his list of sports required by the residents on the website. Action D.P. and D.C.J 5. Yvonne’s resignation. She confirmed to D.P. that she will remain a trustee until the next A.G.M and wants to be kept informed with minutes and correspondence. 6. Tony Thorncroft. D.P. said she had sent a letter to Tony with the Association regrets on Valerie’s death. 7. Treasurer’s report. D.C.J said although there had been £500 in the account, there is now a deficit of £10, having paid AIRs for last year’s consultation and the annual subscription. We now have to pay for 2015. A tier 2 subscription to AIRs Community Buildings Advisory Services to Sept. 2015 £180 (inc VAT). Advisory visit and follow up to assist the CA with community hall funding towards design fees for a new multi purpose building, incorporating/linking with changing facilities for SFC. -

GLA Letter Template

Development & Environment Directorate City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA Switchboard: 020 7983 4000 Minicom: 020 7983 4458 Sharon Mitchell Web: www.london.gov.uk Planning, Rege neration & Conservation Dept. Our ref: PDU/0565a/TT01 Croydon Council Your ref: 09/03502/P Taberner Hous e Date: 4 January 2010 Park Lane Croydon CR9 1JT Dear Ms Mitchell, Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008 Former Greenfields School Site, Pioneer Place, Featherbed Lane, Croydon, CR0 9AW Local Planning Authority Reference: 09/03502/P I refer to your letter received on 17 December 2009 consulting the Mayor of London on the above planning application, which is referable under Category 3D of the Schedule to the Order 2008. I have assessed the details of the application and have concluded that the proposal for renewal of previous planning approval 02/01390/P for demolition of existing buildings; erection of single/two storey building for use as residential care home for 32 persons in connection with the primary use of the site for religious purposes does not raise any new strategic planning issues, that have not already been addressed when the Mayor considered the previous scheme. Therefore, under article 5(2) of the above Order the Mayor of London does not need to be consulted further on this application. Your Council may, therefore, proceed to determine the application without further reference to the GLA. I will be grateful, however, if you would send me a copy of any decision notice and section 106 agreement. -

A Review of Heritage Assets in Lavant

A REVIEW OF HERITAGE ASSETS IN LAVANT Lavant Neighbourhood Development Plan 2016 - 2031 Lavant Parish Council December 2016 2 | INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................... 4 How can heritage assets protected? .................................................... 6 International & National Designations ............................................ 6 Local Designations ........................................................................... 6 Existing designations in Lavant ............................................................. 7 2.0 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................... 10 Guidance for assessing the criteria ....................................................11 3.0 ASSESSMENT OF BUILDINGS AND FEATURES ....................................... 12 4.0 CONCLUSIONS ....................................................................................... 14 APPENDIX 1 - Existing designations in Lavant APPENDIX 2 - Detailed Assessment of Heritage Assets INTRODUCTION | 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.03 This document will assess whether the above heritage assets should be given special attention in the neighbourhood development plan. 1.01 It has become clear through consultation exercises that Lavant’s heritage is important to people that live and work in the community. Local buildings and their relationship -

Uncovering the Past

UNCOVERING THE PAST Archaeological discoveries in Chichester Harbour AONB 2004–2007 Counties of West Sussex and Hampshire June 2007 Archaeology Service www.conservancy.co.uk Sept 2007 UNCOVERING THE PAST Archaeological discoveries in Chichester Harbour AONB 2004–2007 Counties of West Sussex and Hampshire National Grid Reference: 472680 105845, 474475 97505, 484020 100890, 484230 104605 Project Manager Peter Rowsome Author Antony Francis Graphics Carlos Lemos Jeannette Mcleish Museum of London Archaeology Service © Museum of London 2007 Mortimer Wheeler House, 46 Eagle Wharf Road, London N1 7ED tel 020 7410 2200 fax 020 7410 2201 email [email protected] web www.molas.org.uk www.conservancy.co.uk Sept 2007 Chichester Harbour AONB ‘Uncovering the past’ © MoLAS Table Of Contents Introduction 1 Dates used in this report 2 Archaeological and historical development 3 Timeline 3 Palaeolithic – 450,000-12,000 BC 3 Mesolithic – 12,000-4,000 BC 3 Neolithic – 4,000-2,000 BC 4 Bronze Age – 2,000-600 BC 5 Iron Age – 600 BC-AD 43 5 Prehistoric – 450,000 BC-AD 43 6 Roman – AD 43-410 6 Medieval – AD 410-1485 7 Post-medieval – AD 1485-1900 7 Modern – 1900-present 8 Themes 8 Human occupation and movement 8 Land use and development 9 Habitats 10 The maritime environment 11 Sea defences and managed re-alignment 11 Climate change 12 Archaeology and the historic environment 12 The results of the projects 13 Maritime charts 13 i P:\WSUS\1043\na\Field\Synthesis of archaeological work\Final reports\Accessiblesynthesis12-06-07.DOC www.conservancy.co.uk Sept 2007