Peter Gizzi's Hypothetical Lyricism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Tate - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Tate - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Tate(8 December 1943 -) James Tate is an American poet whose work has earned him the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. He is a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. <b>Early Life</b> James Vincent Tate was born in Kansas City, Missouri. He received his B.A. from Kansas State University in 1965 and then went on to earn his M.F.A. from the University of Iowa in their famed Writer's Workshop. <b>Career</b> Tate has taught creative writing at the University of California, Berkeley and Columbia University. He currently teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where he has worked since 1971. He is a member of the poetry faculty at the MFA Program for Poets & Writers, along with Dara Wier and Peter Gizzi. Dudley Fitts selected Tate's first book of poems, The Lost Pilot (1967) for the Yale Series of Younger Poets while Tate was still a student at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop; Fitts praised Tate's writing for its "natural grace." Despite the early praise he received Tate alienated some of his fans in the seventies with a series of poetry collections that grew more and more strange. He has published two books of prose, Dreams of a Robot Dancing Bee (2001) and The Route as Briefed (1999). His awards include a National Institute of Arts and Letters Award, the Wallace Stevens Award, a Pulitzer Prize in poetry, a National Book Award, and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. -

The Matrix of Poetry: James Schuyler's Diary

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies and the Institute of EnglishVol. 11 (Autumn Studie 2017)s, University of Warsaw Vol. 8 (2014) Special Issue Technical Innovation in North American Poetry: Form, Aesthetics, Politics Edited by Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk AMERICAN STUDIES CENTER UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 11 (Autumn 2017) Special Issue Technical Innovation in North American Poetry: Form, Aesthetics, Politics Edited by Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk Warsaw 2017 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWER Paulina Ambroży TYPESETTING AND GRAPHIC DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Bluescape” from the series “New York City.” By permission. https://www.flickr.com/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733–9154 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02–653 Warsaw www.paas.org.pl Nakład: 140 egz. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk From the Editors ......................................................................................................... 271 Joanna Orska Transition-Translation: Andrzej Sosnowski’s Translation of Three Poems by John Ashbery ......................................................................................................... 275 Mikołaj Wiśniewski The Matrix of Poetry: James Schuyler’s Diary ...................................................... 295 Tadeusz Pióro Autobiography and the Politics and Aesthetics of Language Writing ............... -

An Education in Space by Paul Hoover Selected Poems Barbara

An Education in Space by Paul Hoover Selected Poems Barbara Guest Sun & Moon Press, 1995 (Originally published in Chicago Tribune Books, November 26, 1995) Born in North Carolina in 1920, Barbara Guest settled in New York City following her graduation from University of California at Berkeley. Soon thereafter, she came into contact with James Schuyler, Frank O'Hara, John Ashbery, and Kenneth Koch, who, with Guest, would later emerge as the New York School poets. Influenced by Abstract Expressionism, Surrealism, and in general French experiment since Rimbaud and Mallarmé, the group would bring wit and charm to American poetry, as well as an extraordinary visual sense. Guest was somewhat belatedly discovered as a major figure of the group. In part, this has to do with her marginalized position as a woman. But it is also due to a ten-year hiatus in her production, from the long poem The Türler Losses (1979) to her breakthrough collection Fair Realism (1989). In the intervening period, Guest produced Herself Defined (1984), an acclaimed biography of the poet H.D. Ironically, it was a younger generation to follow the New York School, the language poets, who would give her work its new status. Given their attraction to what poet Charles Bernstein calls “mis-seaming,” a style in which the seams or transitions have as much weight as the poetic fabric, it’s surprising that the language poets would so value Guest’s often lyrical and metaphysical poetry. In her poem ‘The Türler Losses,’ for instance, “Loss gropes toward its vase. Etching the way. / Driving horses around the Etruscan rim.” In an earlier work, ‘Prairie Houses,’ Guest wrote of the prairie, “Regard its hard-mouthed houses with their / robust nipples the gossamer hair,” lines which have their visual equivalent in the Surrealist paintings of Paul Delvaux and Rene Magritte. -

Terrel Hale Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0c6034sm No online items Terrel Hale Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2005 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Terrel Hale Papers MSS 0586 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Terrel Hale Papers Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0586 Physical Description: 6 Linear feet(15 archives boxes) Date (inclusive): 1975-2003 Abstract: Papers of Terrel Hale, American poet and editor, dating from 1975 to 2003. Included are original notebooks, typescripts, and drafts of Hale's prose, poetry, and plays; proofs, typescripts, paste-ups, lists of contributors, and correspondence related to the publication of Screens and Tasted Parallels. Preferred Citation Terrel Hale Papers, MSS 586. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. Biography Terrel D. Hale worked as the librarian for the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. where he compiled United States Sanctions and South Africa : A Selected Legal Bibliography. He edited a journal of new poetry titled Screens and Tasted Parallels and his own poems have appeared in several small press magazines and journals. He also authored a chapbook titled Light Still Enough to Witness and had his novel, Saints and Latin Decadence published in 2001. Restrictions Original material deemed too fragile to handle has been photocopied. These preservation photocopies must be used in place of the originals. Scope and Content of Collection The Terrel Hale Papers document Hale's career as a poet, editor, and librarian, as well as the short-lived production of the literary journal Screens and Tasted Parallels, edited by Hale. -

Selected Poems, 1945

UC-Creeley_45-05.qxd 6/22/07 11:27 AM Page 1 Introduction ROBERT CREELEY WAS BORN in Arlington, Massachusetts, in 1926, and grew up in rural West Acton. His father’s side of the family was well es- tablished in the state, but Creeley was raised in closer proximity to his mother’s people, who came from Maine. When he was four, his father died of pneumonia. This was followed closely by the removal of Creeley’s left eye, injured by shattered glass a few years before, and by the straitened circumstance of the Great Depression. His mother, a nurse, kept care of the family—Creeley had an older sister—and his mother’s character, his mother’s habits, necessarily left a strong imprint on his own. (“My cheek- bones resonate/with her emphasis,” he writes in “Mother’s Voice” [000].) Influential also were the losses and uncertainties, the drop in status, which left their mark in patterns of thought, attitude, and behavior. The trajec- tory of Creeley’s adult life, his travels, employments, friendships, house- holds, and loves, is but one trace of a deeper restlessness also recorded in his work—or so it is tempting to think given Creeley’s enduring fascina- tion with contingency and his frequent return, in writing and conversa- tion, to the biographical facts cited above. Yet the import of a fact is never a fact. Life itself is, like writing, an act of interpretation. “Whatever is pre- sumed of a life that designs it as a fixture of social intent, or form of fam- ily, or the effect of an overwhelming event, has little bearing here, even if one might in comfortable hindsight say that it all followed.”1 Disjunction, indeed, played an important role for Creeley—his refusals were often as important as what he embraced. -

$5.00 #219 April-JUNE 2009 New Poetry from Coffee House Press

$5.00 #219 APRIL-JUNE 2009 New Poetry from Coffee House Press Portrait and A Toast in Dream: the House New and of Friends Selected Poems POEMS BY BY BILL BERKSON AKILAH OLIVER ISBN: 978-1-56689-229-2 ISBN: 978-1-56689-222-3 The major work from Bill Berkson, “a “A Toast in the House of Friends brings us serene master of the syntactical sleight and back to life via the world of death and transformer of the mundane into the dream . Akilah Oliver’s book is an miraculous.” (Publishers Weekly) extraordinary gift for everyone.” —Alice Notley Coal Mountain The Spoils Elementary POEMS BY POEMS BY TED MATHYS MARK NOWAK WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY IAN TEH ISBN: 978-1-56689-228-5 ISBN: 978-1-56689-230-8 “A tribute to miners and working people “Reading Mathys, one remembers that everywhere . [Coal Mountain Elementary] poetry isn’t a dalliance, but a way of sorting manages, in photos and in words, to por- through life-or-death situations.” tray an entire culture.” —Howard Zinn —Los Angeles Times � C O M I N G S O O N � Beats at Naropa, an anthology edited by Anne Waldman and Laura Wright Poetry from Edward Sanders, Adrian Castro, Mark McMorris, and Sarah O’Brien Good books are brewing at www.coffeehousepress.org THE POETRY PROJECT ST. MARK’S CHURCH in-the-BowerY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.com #219 april-june 2009 NEWSLETTER EDITOR John Coletti DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. -

Issue Is Dedicated to Him

It fo llows that once these principles are admitted, only time and circum stances are needed fo r the monad or the polyp to finish by transforming itself, gradually and indifferently, into a frog, a swan or an elephant .... A system resting upon such bases may entertain the imagination of a poet, but it cannot for a moment support the examination of anyone who has dissected a hand, a vital organ, or a mere fe ather. -Georges Cuvier I recall that in that period this kind of Pegasean stunt was all the rage. -Blache to Frenu, in Raymond Roussel's The Dust ofSuns Fti. .z. FIG. I-THE GER\1: :\ JOlR:'i.\l OF POETIC RESE.-'RCII The Germ Poetic Research Bloc #I Fall 1997 Editors: Macgregor Card & Andrew Maxwell Layout and Design: as above Cover Art and Insert Icon: Rikki Ducornet Artist acknowledgements appear in the back. §The editors would like to thank Alan Gilbert, Andrew Joron, I van Seitzel and Greg Reynolds. Special thanks go to Peter Gizzi who, by advice and example, lent a singular ballast to this "craft." Our first issue is dedicated to him. Furthermore, in the oblique light of tradition, we would like to acknowledge our predecessors, the original P. R. B., whose tropic yet glanus such green space as this (" ... all, all, verily/ But just that which would save me; these things flit."-William Morris). §This journal has been partially funded by a grant from The Given Foundation. As patronage is perhaps the most precarious factor in the adventure of small press publishing, we are grateful for any measure of assistance. -

On Robert Creeley (2005)

ROBERT CREELEY, 1926 - 2005 Poetry happens for so many reasons. Robert Creeley once said “I seem to be given to work in some intense moment of whatever possibility, and if I manage to gain the articulation necessary in that moment, then happily there is the poem.” It would be hard to overestimate the courage of Robert Creeley, who left Harvard’s manicured grounds in his early-20s to become the poet Charles Olson would call “the figure of outward.” Even at their most interior moments, his poems are concise projections outward of the manifold and vulnerable workings of the human psyche. Olson, 15 years his senior, dedicated his life- work, The Maximus Poems, to Creeley, and in one of his most famous poems, referred to him as the man who gave him “the world,” a tribute to the acts of imagination that Bob made possible through his poems, his belief, and even his conversation. This spring we lost one of the great believers in poetry and its power to transform life and modes of thought into a more complex, resonant, nuanced reality; a poet who never lost sight of the politics that attend those thoughts and feelings. A poet who found a form to accommodate what Wallace Stevens called the violence from within that presses against the violence from without. His poems are precise and knowing and have what one of his early books call “the charm.” Each word in a Creeley poem is chosen with such great Yankee economy that it resonates with several possible tones in quick succession—the way “hello” can register anything from surprise to friendship to a call for help, and—in an effect that’s pure Creeley—often conveys all these messages at once. -

An Interview with Richard Deming

by Annie Freshwater The Activity of Language: An Interview with Richard Deming The first time I heard of Richard Deming was not at a poetry reading or a lecture on American literature. It was rather on the fifty-fourth floor of a condominium complex in Chicago, on Valentine’s Day, at a late-night gathering of poets, artists, professors, and literati. Snow was falling in crystalline drifts onto the river far below the balcony; from where I stood braced against the railing, I could hear the excited talk and easy laughter of the guests inside. Worn out from the day’s round of events at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs annual conference, which I was attending for the first time to present a pedagogy paper, I was more than content to just listen. I spent part of my evening talking with Nancy Kuhl, an exceptionally talented poet and the wife of Richard Deming. In the course of our conversation, Richard’s name came up; I recalled then that I, in fact, owned a book of his poetry, bought for a poetry class I was taking that semester. Nancy’s Wife of the Left Hand is among my favorite books of poetry, so learning that Let’s Not Call It Consequence was written by her husband sparked a new interest in the volume. We parted ways as the party wound down to a close, set to meet again later in the spring when Richard and she would be reading at Chapman University. Richard Deming, I soon learned, is a singularly intriguing individual. -

Press Release

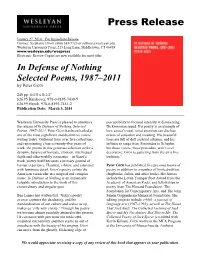

Press Release January 27, 2014—For Immediate Release Contact: Stephanie Elliott (860) 685-7723 or [email protected] Wesleyan University Press, 215 Long Lane, Middletown, CT 06459 www.wesleyan.edu/wespress Electronic Review Copies are now available for most titles. In Defense of Nothing Selected Poems, 1987–2011 by Peter Gizzi 240 pp. 6-1/8 x 8-1/4” $26.95 Hardcover, 978-0-8195-7430-5 $20.99 Ebook, 978-0-8195-7431-2 Publication Date: March 3, 2014 Wesleyan University Press is pleased to announce perceptibility to focused intensity at disorienting, the release of In Defense of Nothing, Selected Dickinsonian speed. His poetry is an example of Poems, 1987–2011. Peter Gizzi has been hailed as how a poet’s total, tonal attention can disclose one of the most significant and distinctive voices orders of sensation and meaning. His beautiful writing today. Gathered from over five collections, lines are full of deft archival allusion, and his and representing close to twenty-five years of influences range from Simonides to Schuyler, work, the poems in this generous selection strike a but those voices, those prosodies, aren’t ever dynamic balance of honesty, emotion, intellectual decorative; Gizzi is gathering from the air a live depth and otherworldly resonance—in Gizzi’s tradition.” work, poetry itself becomes a primary ground of human experience. Haunted, vibrant, and saturated Peter Gizzi has published five previous books of with luminous detail, Gizzi’s poetry enlists the poetry in addition to a number of limited-edition American vernacular in a magical and complex chapbooks, folios, and artist books. -

An Interview with Elizabeth Willis by Mark Tursi

An Interview with Elizabeth Willis1 Preface: Writing the Music of Thought In a review of Elizabeth Willis’s Turneresque, Lisa Smith writes: Despite the tension between what we do and what is done to us, and all the blurry possibilities that this entails, Willis celebrates personal effort—a sort of Foucauldian self-fashioning with a paint brush in one hand and a movie camera in the other—throughout the text, showing that a universe which seems separate and in constant movement away from us provides another window through which to observe (Smith para 4). This notion of simultaneously self-fashioning with a paintbrush and a movie camera is an apt description of much of Willis’s work. She seems always in two places, two thoughts at once, drawing out what we know, then capturing what we do not or cannot know; sketching what we perceive, then illustrating what we think we perceive. She seems to embrace abstraction while also rejecting it. She critiques sincerity and somehow glorifies it at the same time. In all these efforts, however, she is in some ways, writing the music of thought. Willis’s work is captivating because it seems to do so much at once. She is at the vanguard in this new trajectory of American poets I hesitate to call New Brutalism. The term, “New Brutalists,” was appropriated from Ashbery, and points toward a group of writers from the San Francisco Bay Area who, though fascinated with the processes of thought and imagination and how these impact the relation between reality and the ‘self’ via language, are equally interested in distorting and amplifying our understanding of human experience. -

“Inside/Outsider” Panel Talk; Awp; Chicago, March 2004

“INSIDE/OUTSIDER” PANEL TALK; AWP; CHICAGO, MARCH 2004 I plan to use the topic of this panel loosely as an underpinning. I came here today because of a kind invitation from Eileen Myles, which is to say, I came here out of friendship. The inside/outside is a curious construction. In terms of aesthetics, it makes me think of Stevens’ force of the imagination pushing against the force of reality. Or Nietzsche’s reading of the Apollonian and Dionysian. Also Robin Blaser’s discussion of Jack Spicer’s “practice of outside” resonates here for me. The idea of exposing a real. But in relation to institutions, are we ever outside them? I know that in the mid to late 80’s when I was waiting tables and reading books and editing my journal o·blēk I felt freer than I do now, but then my employment took up less of my mental and psychic time.1 But even then, outside of the quote academy, writing poems and editing my journal, I was already always working within a political institution. As Chomsky reminds us, the American “language is a dialect that has an army and a navy.” So the political reality of working in language is unavoidable. We are never outside it. I am always reminding my students that language is older than us, bigger than us, and it doesn’t live inside us; we live inside it. The inside and outside I think we deal with most is in relation to the work itself, the difficulty of getting inside our work, given the cognitive dissonance of daily life under the rule of the worst president in our history.