Cine-Tracts 16, Vol. 4, No. 4, Winter, 1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State of Quebec

le cinema quebecois the state of quebec Quebec is at a crossroads, and the deci sions - both federal and provincial - which will be made in the coming months are crucial. Taking stock of the situation of feature filming in the province, Jean-Pierre Tadros traces a sombre portrait. by Jean-Pierre Tadros The election of the Parti Quebecois has created a sort of been given. It remains to be seen whether the government 'before and after' effect, a temptation to evaluate what had can and will take the proper steps to help the industry out come before in order to better measure what is to come of its economic and spiritual depression. Perhaps it is al afterwards. One would like to look back and say that the ready too late. state of cinema in Quebec on November 15 was strong and For the last few years, there's been an uneasy feeling, healthy, that the directors and producers, not to mention the sense of something going wrong. The 'cinema' milieu the technicians, were in good form. Alas! Nothing could be reflected the malaise which ran through Quebec and which, farther from the truth. To be fair, le cinema quebecois finally, brought in the new government. Perhaps it should is still struggling along but its condition has become have been expected that a generation which was brought up critical. The months ahead will tell whether the illness is during the 'quiet revolution' would have grown up thinking terminal. big. Too big! La folic des grandeurs. Quebec's cinema was to pay dearly for trying to embody those dreams. -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

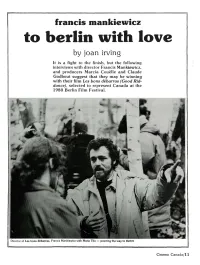

Francis Mankiewicz

francis mankiewicz to berlin with love by joan irving It is a fight to the finish, but the following interviews with director Francis Mankiewicz, and producers Marcia Couelle and Claude Godbout suggest that they may be winning with their film Les bons debarras (Good Rid dance), selected to represent Canada at the 1980 Berlin Film Festival. Director of Les bons debarras, Francis Mankiewicz with Marie Tifo — pointing the way to Berlin! Cinema Canada/11 really didn't know what to think of it, so 1 of my universe. You might find something The year 1980 marks a revival in just set it aside while I finished the other for yourself in it.' Quebecois films. Following the slump of film. But 1 found that 1 was continually the late-seventies — when directors like thinking of Le bons debarras. There was Cinema Canada: It is surprising how Claude Jutra, Gilles Carle, Francis Man •something in that script that haunted me. much in Les bons debarras resembles kiewicz, and others, left Montreal to work At the time there were a lot of opportu the world you created in Le temps d'une in Toronto— several directors, including nities to work in Toronto. What brought chasse. Carle, Mankiewicz, Jean-Claude Labrec- me back to Quebec was Rejean's script. Francis Mankiewicz: It would be difficult que, Andre Forcier and Jean-Guy Noel for me to direct a film in which I didn't find are now completing new features. First to Cinema Canada: Ducharme has pub something I could feel close to. The be released is Mankiewicz's Les bons de lished several novels, but this was his first resemblance is partly style, but mostly, I barras (Good Riddance). -

De Montréal : Le Sacré Et Le Profane

JÉSUS DE MONTRÉAL : LE SACRÉ ET LE PROFANE Danielle Conway Mémoire présenté à l'École des Études Supérieures comme exigence partielle de la Maîtrise ès Arts en Études françaises Département d'Études françaises et hispaniques Université Mernorial Saint-Jean, Terre-Neuve août 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 191 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OttawaON KtAW Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or seU reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm. de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts £kom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. RÉs& Ce mémoire consiste essentiellement en une analyse intention sémiotique de Jésus de Montréal, film du cinéaste québécois Denys Arcand sorti en 1989. Ce film est basé sur la confrontation du Sacré et du Profane, comme l'indique le titre du film même (Jésus/Montréal), qui résulte en la folie et la mort du Sujet, le personnage principal, Daniel Coulombe. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

Maurice Proulx

01/10/13 The Clergy and the Origins of Quebec Cinema The Clergy and the Origins of Quebec Cinema: Fathers Albert Tessier and Maurice Proulx par Poirier, Christian A handful of priests were among the first people in Quebec to use a movie camera. They were also among the first to grasp the cultural significance of cinema. Two individuals are particularly significant in this regard: Fathers Albert Tessier and Maurice Proulx. Today they are widely recognized as pioneers of Quebec cinema arts. Since 2000, Quebec cinema has been experiencing renewed popularity. Nevertheless, the key role played by the clergy in the development of a cinematographic and cultural tradition before the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s has not been fully appreciated, even though they managed nothing less than a collective heritage acquisition of cinema during a period dominated by foreign productions. After initially opposing the cinema-considering it an "imported" invention capable of corrupting French-Canadian youth- the clergy gradually began to promote the showing of movies in parish halls, church basements, schools, colleges and convents. It came to see film as yet another tool for conveying Catholic values. Article disponible en français : Clergé et patrimoine cinématographique québécois : les prêtres Albert Tessier et Maurice Proulx A Society on the Threshold between the Traditional Past and the Modern World During the first half of the 20th century, Quebec society underwent a process of gradual change: it became more industrialized, urbanized and economically diverse, while modern ideas such as liberalism or secularism increasingly became accepted as credible alternatives. Nevertheless, for the political and intellectual elite, the values associated with traditions, Catholicism, and rural life were still the of the French-Canadian people's identity. -

Mirror of Simulation in Denys Arcand's "Jesus of Montreal"

THE MIRROR OF SIMULATION IN DENYS ARCAND ’ S JESUS OF MONTREAL By Robert J. Roy Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Literature Chair: / Jeffpey MjddenfsSs^ David L. Pike Dean 6f the College Date 0 2006 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1437772 Copyright 2006 by Roy, Robert J. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1437772 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © COPYRIGHT by Robert J. Roy 2006 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE MIRROR OF SIMULATION IN DENYS ARC AND ’ S JESUS OF MONTREAL BY Robert J. -

Truth in Cinema

Truth in Cinema http://web.mit.edu/candis/www/callison_truth_cinema.htm Truth in Cinema Comparing Direct Cinema and Cinema Verité Candis Callison Documenting Culture, CMS 917 November 14, 2000 Like most forms of art and media, film reflects the eternal human search for truth. Dziga Vertov was perhaps the first to fully articulate this search in “Man with a Movie Camera.” Many years later he was finally followed by the likes of Jean Rouch, Richard Leacock and Fred Wiseman who, though more provocative and technologically advanced, sought to bring reality and truth to film. Edgar Morin describes it best when, in reference to The Chronicle of a Summer , he said he was trying to get past the “Sunday best” portrayed on newscasts to capture the “authenticity of life as it is lived” 1. Both direct cinema and cinema verité hold this principle in common – as I see it, the proponents of each were trying to lift the veneer that existed between audience and subject or actor. In a mediated space like film, the veneer may never completely vanish, but new techniques such as taking the camera off the tripod, using sync sound that allowed people to speak and be heard, and engaging tools of inquiry despite controversy were and remain giant leaps forward in the quest for filmic truth. Though much about these movements grew directly out of technological developments, they also grew out of the social changes that were taking place in the 1960s. According to documentary historian Erik Barnouw, both direct cinema and cinema verité had a distinct democratizing effect by putting real people in front of the camera and revealing aspects of life never before captured on film. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Political Science 315/North American Studies 315 Politics and Society In

Political Science 315/North American Studies 315 Politics and Society in Contemporary Quebec Wilfrid Laurier University Winter 2017 Instructor: Dr. Brian Tanguay Lecture Time: Tu 4:00-6:50pm Classroom: 1C18 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: W 3:00-4:30pm Office: DAWB 4-160 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course examines the sources of contemporary Québécois identity through the lenses of fiction, film, and social science. It explores both the legacy of Québec’s distinctive historical trajectory and recent political, economic, and social developments in the province, along with their impact on public policy. It also examines Québec’s relations with the rest of Canada, the situation of Francophones outside of Québec, and Québec’s aspirations to be an actor in the international arena. Classes will consist of a mixture of lectures (for the first hour and twenty minutes) and tutorials (for the final hour or so). COURSE LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end of the course students should: • have a greater understanding of the historical, political and cultural forces that have shaped contemporary Quebec • be able to identify some of the ways in which Quebec is, de facto, a “distinct society” within Canada • have greater familiarity with a variety of interdisciplinary approaches to the study of Quebec • have improved their ability to work in a group, as well as individually • have improved their presentation and public speaking skills • have improved their reading comprehension and writing skills 1 REQUIRED TEXTS Stéphan Gervais, Christopher Kirkey, and Jarrett Rudy, eds., Quebec Questions: Quebec Studies for the Twenty-First Century, 2nd ed. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2016. -

Département D'anthropologie Faculté Des Arts Et Sciences

Université de Montréal LA COLLABORATION CHEZ PIERRE PERRAULT : ÉTUDE COMPARATIVE DE POUR LA SUITE DU MONDE ET LA BÊTE LUMINEUSE par Benoit Vachon Département d’Anthropologie Faculté des Arts et Sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des Arts et Sciences en vue de l’obtention du grade de M. Sc. en Anthropologie Avril 2013 © Benoit Vachon, 2013 Université de Montréal Faculté Arts et Sciences Ce mémoire intitulé : LA COLLABORATION CHEZ PIERRE PERRAULT : ÉTUDE COMPARATIVE DE POUR LA SUITE DU MONDE ET LA BÊTE LUMINEUSE présenté par : Benoit Vachon a été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : ROBERT CRÉPEAU F.A.S. - Anthropologie Président-rapporteur BOB WHITE F.A.S. - Anthropologie Directeur de recherche JOHN LEAVITT F.A.S. - Anthropologie Membre du jury iii Résumé Ce mémoire propose une analyse de la collaboration à l’intérieur de projets cinématographiques dans l’œuvre de Pierre Perrault. Comme la collaboration entre cinéaste et participants soulève des questions éthiques, cette recherche étudie deux films pivots dans la carrière de ce cinéaste soit Pour la suite du monde et La bête lumineuse. Tout en contrastant le discours du cinéaste avec celui d’un protagoniste nommé Stéphane-Albert Boulais, cette étude détaille les dynamiques de pouvoir liées à la représentation et analyse l’éthique du créateur. Ce mémoire présente une description complète de la pensée de Pierre Perrault, ainsi que sa pratique tant au niveau du tournage que du montage. Cette étude se consacre à deux terrains cinématographiques pour soulever les pratiques tant au niveau de l’avant, pendant, et après tournage. Ce mémoire se penche ensuite sur Stéphane-Albert Boulais, qui grâce à ses nombreux écrits sur ses expériences cinématographiques, permet de multiplier les regards sur la collaboration. -

Cinema Verite : Definitions and Background

Cinema Verite : Definitions and Background At its very simplest, cinema verite might be defined as a filming method employing hand-held cameras and live, synchronous sound . This description is incomplete , however, in that it emphasizes technology at the expense of filmmaking philosophy. Beyond recording means, cinema verite indicates a position the filmmaker takes in regard to the world he films. The term has been debased through loose critical usage, and the necessary distinction between cinema-verite films and cinema -verite techniques is often lost. The techniques are surely applicable in many filming situations, but our exclusive concern here is for cinema-verite documentaries , as will become clear through further definition. Even granting the many film types within the cinema-verite spectrum (where, for instance, most Warhol films would be placed), it is still possible to speak of cinema verite as an approach divorced from fictional elements. The influence of fictional devices upon cinema-verite documentaries is an important issue, but the two can be spoken of as separate entities. Cinema verite in many forms has been practiced throughout the world , most notably in America , France, and Canada. The term first gained popular currency in the early sixties as a description of Jean Rouch's Chronique d 'un Ete. To embrace the disparate output of Rouch, Marker, Ruspoli, Perrault, Brault, Koenig, Kroi- tor, Jersey, Leacock, and all the others under one banner is to obscure the wide variance in outlook and method that separates American cinema verite from the French or Canadian variety and further to fail to take into account differences within the work of one country or even one filmmaker .