Maximilian Prince of Wied-Neuwied and His Ethnographic Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Os Processos De Midiatização Da Cozinha Paulista: Do Arraial À Metrópole / Lucia Helena Soares De Lima

UNIVERSIDADE ANHEMBI MORUMBI LUCIA HELENA SOARES DE LIMA OS PROCESSOS DE MIDIATIZAÇÃO DA COZINHA PAULISTA: do Arraial à metrópole SÃO PAULO 2011 LUCIA HELENA SOARES DE LIMA OS PROCESSOS DE MIDIATIZAÇÃO DA COZINHA PAULISTA: do Arraial à metrópole Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada à Banca Examinadora, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre do Programa de Mestrado em Comunicação, área de concentração em Comunicação Contemporânea da Universidade Anhembi Morumbi, sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Gelson Santana SÃO PAULO 2011 L698p Lima, Lucia Helena Soares de Os processos de midiatização da cozinha paulista: do arraial à Metrópole / Lucia Helena Soares de Lima. – 2011. 143f.: il.; 30 cm. Orientador: Gelson Santana Dissertação (Mestrado em Comunicação) - Universidade Anhembi Morumbi, São Paulo, 2011. Bibliografia: f.127-135. 1. Comunicação. 2. Midiatização. 3. Cozinha paulista. 4. Cultura alimentar. 5. Modernização. 6. Rádio. 7. Televisão. 8. Processos. I. Título. CDD 302.2 LUCIA HELENA SOARES DE LIMA OS PROCESSOS DE MIDIATIZAÇÃO DA COZINHA PAULISTA: do Arraial à metrópole Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada à Banca Examinadora, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre do Programa de Mestrado em Comunicação, área de concentração em Comunicação Contemporânea da Universidade Anhembi Morumbi, sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Gelson Santana Aprovado em ----/-----/----- Prof. Dr. Gelson Santana Profª. Drª. Maria Ignês Carlos Magno Prof. Dr. João Luiz Maximo Dedicatória Aos meus santos protetores São Benedito (padroeiro dos cozinheiros) e Nossa Senhora Aparecida (padroeira do Brasil)! À minha bisavó, D. Quinoca que tirou de seu tabuleiro de doces o sustento de seus filhos, deixando seu legado como herança no imaginário da nossa família! Ao meu pai, Seu Soares, e D. -

Stadt Linz Am Rhein

Stadt Linz am Rhein Integriertes Städtebauliches Entwicklungskonzept mit Vorbereitender Untersuchung gemäß § 141 BauGB Historischer Stadtbereich „Altstadt Linz am Rhein“ Erläuterungsbericht Bearbeitet im Auftrag der Stadt Linz am Rhein Seite 2, Integriertes Städtebauliches Entwicklungskonzept, Historischer Stadtbereich „Altstadt Linz am Rhein“ Erläuterungsbericht, April 2016 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Anlass und Ziel des Städtebaulichen Entwicklungskonzeptes .............................6 1.1 Förderprogramm „Historische Stadtbereiche“ ...........................................6 1.2 Programmgebiet „Altstadt Linz am Rhein“................................................8 1.3 Methodik/Vorgehensweise................................................................... 11 2. Allgemeine Grundlagen .............................................................................. 12 2.1 Lage und Verkehrsanbindung ............................................................... 12 2.2 Historische Siedlungsentwicklung ......................................................... 15 2.3 Übergeordnete Planungen und Zielsetzungen .......................................... 19 3. Beteiligungsprozess ................................................................................... 25 3.1 Informationsveranstaltungen ................................................................ 25 3.2 Arbeitskreise ..................................................................................... 27 3.3 Eigentümerbefragung ......................................................................... -

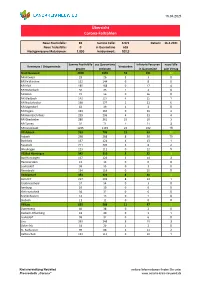

Übersicht Corona-Fallzahlen

16.04.2021 Übersicht Corona-Fallzahlen Neue Positivfälle: 83 Summe Fälle: 6.971 Datum: 16.4.2021 Neue Todesfälle: 0 in Quarantäne 618 Nachgewiesene Mutationen: 1.050 Inzidenzwert: 202,9 Summe Positivfälle aus Quarantäne Infizierte Personen neue Fälle Kommune / Ortsgemeinde Verstorben gesamt entlassen in Quarantäne zum Vortag Stadt Neuwied 2950 2659 53 291 42 NR Altwied 29 26 3 3 0 NR Feldkirchen 152 144 0 8 0 NR Irlich 185 168 0 17 4 NR Rodenbach 30 26 1 4 0 NR Block 72 56 0 16 0 NR Gladbach 142 127 4 15 1 NR Niederbieber 198 177 1 21 6 NR Segendorf 42 39 1 3 0 NR Engers 194 165 0 29 4 NR Heimbach-Weis 239 206 4 33 4 NR Oberbieber 280 261 15 19 3 NR Torney 92 71 1 21 3 NR Innenstadt 1295 1193 23 102 16 VG Asbach 769 706 15 63 17 Asbach 298 268 8 30 10 Buchholz 137 124 4 13 1 Neustadt 211 203 3 8 2 Windhagen 123 111 0 12 5 VG Bad Hönningen 342 310 3 32 3 Bad Hönningen 137 123 3 14 3 Hammerstein 13 13 0 0 0 Leutesdorf 58 55 0 3 0 Rheinbrohl 134 119 0 15 0 VG Dierdorf 353 323 8 30 1 Dierdorf 217 203 8 14 1 Großmaischeid 57 54 0 3 0 Isenburg 16 10 0 6 0 Kleinmaischeid 38 32 0 6 0 Marienhausen 14 13 0 1 0 Stebach 11 11 0 0 0 VG Linz 635 588 11 47 7 Dattenberg 40 38 0 2 0 Kasbach-Ohlenberg 41 40 0 1 1 Leubsdorf 38 32 0 6 0 Linz 263 248 8 15 3 Ockenfels 31 29 1 2 0 St. -

Juizado Especial Cível E Criminal End.: Av

JUIZADOS ESPECIAIS E INFORMAIS DE CONCILIAÇÃO E SEUS ANEXOS 2. COMARCAS DO INTERIOR ADAMANTINA – Juizado Especial Cível e Criminal End.: Av. Adhemar de Barros, 133 - Centro CEP: 17800-000 Fone: (18) 3521-1814 Fax: (18) 3521-1814 Horário de Atendimento aos advogados: das 09 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento aos estagiários: das 09 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento ao público: das 12:30 às 17 horas Horário de Triagem: das 12:30 às 17 horas ➢ UAAJ - FAC. ADAMANTINENSES INTEGRADAS End.: Av. Adhemar de Barros, 130 - Centro Fone: (18) 3522-2864 Fax: (18) 3502-7010 Horário de Funcionamento: das 08 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento aos advogados: das 08 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento ao Público: das 08 às 18 horas AGUAÍ – Juizado Especial Cível End.: Rua Joaquim Paula Cruz, 900 – Jd. Santa Úrsula CEP: 13860-000 Fone: (19) 3652-4388 Fax: (19) 3652-5328 Horário de Atendimento aos advogados: das 09 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento aos estagiários: das 10 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento ao público: das 12:30 às 17 horas Horário de Triagem: das 12:30 às 17 horas ÁGUAS DE LINDÓIA – Juizado Especial Cível e Criminal End.: Rua Francisco Spartani, 126 – Térreo – Jardim Le Vilette CEP: 13940-000 Fone: (19) 3824-1488 Fax: (19) 3824-1488 Horário de Atendimento aos advogados: das 09 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento aos estagiários: das 10 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento ao público: das 12:30 às 18 horas Horário de Triagem: das 12:30 às 17 horas AGUDOS – Juizado Especial Cível e Criminal End.: Rua Paulo Nelli, 276 – Santa Terezinha CEP: 17120-000 Fone: (14) 3262-3388 Fax: (14) 3262-1344 (Ofício Criminal) Horário de Atendimento aos advogados: das 09 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento aos estagiários: das 10 às 18 horas Horário de Atendimento ao público: das 12:30 às 18 horas Horário de Triagem: das 12:30 às 17 horas ALTINÓPOLIS – Juizado Especial Cível e Criminal End.: Av. -

Für Die Haushaltsjahre 2020/2021 Haushaltssatzung Und Haushaltsplan Der Ortsgemeinde Rodenbach

Haushaltssatzung und Haushaltsplan der Ortsgemeinde Rodenbach für die Haushaltsjahre 2020/2021 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seiten 1. Haushaltssatzung 1 - 2 2. Vorbericht 3 - 13 3. Gesamt-Ergebnishaushalt und Finanzhaushalt 15 - 19 4. Teilergebnis- und Teilfinanzhaushalt 21 - 24 5. Finanzplan B -Investitionsmassnahmen- 25 - 35 6. Produktübersicht 37 - 38 7. Produktbuch mit Beschreibungen 39 - 57 8. Ergebnishaushalt auf Produktebene 59 - 89 9. Stellenplan 91 10. Berechnung der freien Finanzspitze 92 11. Bewirtschaftungsregeln 93 Übersicht über den Stand der Kreditaufnahmen und 12. ähnlicher Vorgänge 94 13. Übersicht Jahresergebnisse Ergebnishaushalt 95 14. Übersicht Jahresergebnisse Finanzhaushalt 96 15. Übersicht über die Entwicklung des Eigenkapitals 97 17. Bilanz des letzten Haushaltsjahres, für das ein Jahresabschluss vorliegt 98 - 100 Haushaltssatzung der Ortsgemeinde Rodenbach für die Haushaltsjahre 2020/2021 vom Der Ortsgemeinderat hat auf Grund von § 95 Gemeindeordnung in der derzeit geltenden Fassung folgende Haushaltssatzung beschlossen, die nach Genehmigung durch die Kreisverwaltung Neuwied als Aufsichtsbehörde vom hiermit bekannt gemacht wird: § 1 Ergebnis- und Finanzhaushalt Haushaltsjahr Festgesetzt werden 2020 2021 1. im Ergebnishaushalt der Gesamtbetrag der Erträge auf 762.100,00 € 774.265,00 € der Gesamtbetrag der Aufwendungen auf 872.370,00 € 848.786,00 € der Jahresüberschuss / Jahresfehlbedarf auf -110.270,00 € -74.521,00 € 2. im Finanzhaushalt Saldo der ordentlichen und außerordentlichen Ein- und Auszahlungen -76.310,00 € -39.716,00 -

DE-5510-302 Rheinhänge Zwischen Unkel Und Neuwied

Landesforsten Rheinland-Pfalz Forstfachlicher Beitrag zum FFH-Bewirtschaftungsplan DE-5510-302 Rheinhänge zwischen Unkel und Neuwied Forstfachlicher Beitrag zum FFH-Bewirtschaftungsplan "Rheinhänge zwischen Unkel und Neuwied" – DE-5510-302 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Waldbesitzartenverteilung 2. Ansprechpartner / Forstämter 3. Waldfunktionen 4. Gesamtwald und Anteil beplanter Holzbodenfläche 5. Nachhaltsklassen 6. Baumartenverteilung 7. Altersklassenverteilung 8. Waldlebensraumtypen Anhang 1 : Karte der Waldbesitzartenverteilung Anhang 2 : Baumarten und Baumartengruppen Anhang 3 : Abgrenzung der Nachhaltsklassen Anhang 4 : Definition der Entwicklungsphasen Anhang 5 : Altersspannen für Entwicklungsphasen Anhang 6 : Bewirtschaftungsempfehlungen für die relevanten Waldlebensraumtypen Beitrag erstellt am : 13.07.2017 Lebensraumtypen Waldflächen Forstamtsgrenzen Datenstand : 25.01.2017 01.10.2016 01.10.2015 Seite 2 Forstfachlicher Beitrag zum FFH-Bewirtschaftungsplan "Rheinhänge zwischen Unkel und Neuwied" – DE-5510-302 1. Waldbesitzartenverteilung Das Gebiet umfasst insgesamt eine Fläche von 767,78 ha. Der Wald nimmt dabei Fläche von 594,97 ha (77%) ein. Der Anteil der Waldbesitzarten geht aus der folgenden Abbildung hervor. Die räumliche Verteilung ist in der Übersichtskarte (Anhang 1) dargestellt. Abb. 1 Waldbesitzartenverteilung (Flächenverschneidung ATKIS / Daten Landesforsten) Staatswald Kommunalwald Eichen 4% 2% Buchen Buchen Buchen Buchen Buchen Laubbäume langlebig Laubbäume langlebig Laubbäume langlebig Laubbäume langlebig Laubbäume langlebig -

Boletim Da Sala De Situação SP / DAEE 14/02/2021 09:00

SECRETARIA DE INFRAESTRUTURA E MEIO AMBIENTE DEPARTAMENTO DE ÁGUAS E ENERGIA ELÉTRICA Unidade de Gerenciamento de Informações Sobre Cheias – SUP / UGIC Rua Boa Vista, 170 - 11º And – Centro - Cep 01014-000 - São Paulo SP Tel (11) 3293-8461 Fax (11) 3105-8974 - www.daee.sp.gov.br Boletim da Sala de Situação SP / DAEE 14/02/2021 09:00 Observações dos Operadores da SSSP-DAEE de 13/02/2021 08:00 até 14/02/2021 08:00. Queila 13/02/2021 08:00 Chuvas Moderadas em São Caetano do Sul, Santo André, Mauá, Mogi das Cruzes, Guararema, Salesópolis, Jacareí, São José dos Campos, Paraibuna, Caçapava Taubaté, Pindamonhangaba, São Luiz do Paraitinga, Aparecida, Guaratinguetá, Peruíbe, Cubatão, Francisco Morato, Itupeva, Indaiatuba, Valinhos, Campinas Monte Mor, Sumaré, Indaiatuba, Elias Fausto, Itupeva, São Pedro, Socorro, Serra Negra, Pinhalzinho, Concha, Leme, Dois Córregos, Bariri, Espírito Santo do Pinhal, Torrinha, Bocaina, Bariri, Pederneiras e na zona leste da Capital; Fracas em São Lourenço da Serra, Embu-Guaçu, Itapecerica da Serra, Embu das Artes, Taboão da Serra, Mairiporã, Guarulhos, Itaquaquecetuba, Osasco, Itatiba, Bragança Paulista, Juquitiba e na zona sul e norte da Capital. 13/02/2021 09:00 Chuvas moderadas em Mongaguá, Cubatão, Rio Grande da Serra, Santo André, Mauá, São Bernardo do Campo, São Caetano do Sul, Itaquaquecetuba, Guarulhos, Salesópolis, São Sebastião, Guararema, Santa Branca, Paraibuna, Jacareí, Santa Isabel, Ilhabela, São Luiz do Paraitinga, São José dos Campos, Caçapava, Joanópolis, Louveira, Itupeva, Morungaba, Atibaia, Santa Lúcia, Jaboticabal, Jaú, Pederneira, Mogi-Guaçu, Conchal, Araras, Leme e nas zonas leste e centro da Capital; Fracas em Pedreira, Valinhos, Indaiatuba, Campinas, Atibaia, Campo Limpo Paulista, Francisco Morato, Franco da Rocha, Caieiras, Mairiporã, Osasco, São Vicente, Itanhaém e na zona oeste da Capital. -

Kreisverwaltung Neuwied, Spurensuche. Johanna Loewenherz

1 Johanna Loewenherz(1857-1937) Source: Kreisverwaltung Neuwied, Spurensuche. Johanna Loewenherz: Versuch einer Biografie; Copyright: Johanna- Loewenherz-Stiftung 2 Prostitution or Production, Property or Marriage? A Study on the Women´s Movement by Johanna Loewenherz Neuwied. Published by the author, 1895. [Öffentl. Bibliothek zu Wiesbaden, Sig. Hg. 5606] Translated by Isabel Busch M. A., Bonn, 2018 Translator´s Note: Johanna Loewenherz employs a complicated style of writing. The translator of this work tried to stay true to Loewenherz´ style as much as possible. Wherever it was convenient, an attempt was made to make her sentences easier to understand. However, sometimes the translator couldn´t make out Loewenherz´ sense even in the original German text, for instance because of mistakes made by Loewenherz herself. Loewenherz herself is not always consistent in her text; for example when using both the singular and plural forms of a noun or pronoun in the same sentence. The translator of this work further took the liberty of using the singular and plural forms of “man” and “woman” rather randomly, whenever Loewenherz makes generalising remarks on both sexes. Seeing that Loewenherz uses a lot of puns in the original text, the translator of this work explains these in the footnotes. It is to be noted that whenever Loewenherz quotes a person or from another text, the translator of this work either uses already existing translations (e.g. from Goethe´s Faust) or translated them herself. In the former case the sources of these quotes are named in footnotes. The other translations are not specifically marked. 3 A Visit to the Night Caféi What is it that drives a man to the harlot?—How can he bring himself to touch such a woman?— Allow me, Gentlemen, the wholehearted sincerity which convenience usually does not forgive a woman. -

Chronik Der Feuerwehr Bad Hönningen

Chronik der Feuerwehr Bad Hönningen 1900 Mai. Bürgermeister Jakob Conrad gründet die Freiwillige Feuerwehr Hönningen, der zu Beginn 22 Mitglieder angehören. Bertram Rüssel wird der erste Wehrführer, damals Oberführer genannt. Unterkunft für die Freiwillige Feuerwehr bleibt, wie schon für die Pflichtfeuerwehr, das Spritzenhaus am Marktplatz. 1900 Die Wehr gliedert sich in drei Abteilungen. Hierzu zählen die Steiger, die Hydrantenabteilung (oder Spritzenmannschaft) sowie die Hilfs- und Absperrungsabteilung (oder Ordnungsmannschaft). 1902 Juni. Die Wehr veröffentlicht ihre Statuten, die zugleich das älteste vorliegende Schriftstück der Freiwilligen Feuerwehr Hönningen sind. 1903 Franz Both wird der zweite Wehrführer in der Geschichte der Wehr. Er übernimmt das Amt von Vorgänger Bertram Rüssel. 1906 Umzug vom Spritzenhaus am Marktplatz ins neue Gerätehaus an der neuerbauten Schule in der Kaiser-Wilhelmstraße (heute Bischof- Stradmann-Straße). 1907 Zu Übungszwecken wird auf dem Schulhof ein Steigerturm errichtet. 1908 Zur Ausrüstung der Wehrmänner gehören Helme, Mützen, Drillich- und Tuchröcke, Koppel, Steigergurte mit Karabinerhaken, Steigerleinen und Hammerbeile. 1908 Aufstockung der Wehr durch Bürgermeister Görtz von 22 auf 30 Mann. 1908 Der Vorstand beschließt, daß Mitglieder der Werkfeuerwehr der Chemischen Fabrik nicht gleichzeitig der Freiwilligen Feuerwehr angehören dürfen. 1914 Nach dem Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkrieges schrumpft die Wehr auf 11 Mitglieder zusammen. 1918 Im Ersten Weltkrieg müssen mit Heinrich Schmitz und Franz Hornung zwei Kameraden der Wehr ihr Leben lassen. 1919 September. Zum ersten Mal nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg findet sich die Wehr wieder zusammen. Man stellt Beschädigungen an den Feuerwehrgeräten fest. Diese sind während des Krieges aufgrund der Einquartierung der amerikanischen Streitkräfte aus ihrem Depot genommen worden. Johann Krämer wird der dritte Wehrführer in der Geschichte der Wehr. -

Tamarixia Radiata (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 3 Diaphorina Citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae): Mass Rearing and Potential Use of the Parasitoid in Brazil

Journal of Integrated Pest Management (2016) 7(1): 5; 1–11 doi: 10.1093/jipm/pmw003 Profile Tamarixia radiata (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 3 Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae): Mass Rearing and Potential Use of the Parasitoid in Brazil Jose´Roberto Postali Parra, Gustavo Rodrigues Alves, Alexandre Jose´Ferreira Diniz,1 and Jaci Mendes Vieira Departamento de Entomologia e Acarologia, Escola Superior de Agricultura Luiz de Queiroz, Universidade de Sa˜o Paulo, Av. Padua Dias, 11, Piracicaba, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]), and 1Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received 3 July 2015; Accepted 15 January 2016 Downloaded from Abstract Huanglongbing (HLB) is the most serious disease affecting citriculture worldwide. Its vector in the main produc- ing regions is the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, 1908 (Hemiptera: Liviidae). Brazil has the larg- est orange-growing area and is also the largest exporter of processed juice in the world. Since the first detection http://jipm.oxfordjournals.org/ of the disease in this country, >38 million plants have been destroyed and pesticide consumption has increased considerably. During early research on control methods, the parasitoid Tamarixia radiata (Waterston, 1922) (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) was found in Brazil. Subsequent studies focused on its bio-ecological aspects and distribution in citrus-producing regions. Based on successful preliminary results for biological control with T. radiata in small areas, mass rearing was initiated for mass releases in Brazilian conditions. Here, we review the Brazilian experience using T. radiata in D. citri control, with releases at sites of HLB outbreaks, adjacent to commercial areas, in abandoned groves, areas with orange jessamine (a psyllid host), and backyards. -

Diário Oficial Nº

DIaRIO´ OFICIAL MUNICÍPIO DE NOVA ODESSA Nº 698 | Segunda-feira, 23 de Agosto de 2021 | Diário Oficial de Nova Odessa | http://www.novaodessa.sp.gov.br PODER EXECUTIVO DIRETORIA DE SUPRIMENTOS 1 PIETRA DUARTE DE CARVALHO RIBEIRO AMERICANA 2 CAMILA GIERTS JACHETTO FAAL LIMEIRA 3 VITORIA GIERTS JACHETTO FAM AMARICAVA AVISO DE SUSPENSÃO DE LICITAÇÃO TOMADA DE 4 FABIANA JANDIRA BUENO ANHANGUERA SUMARE PREÇOS 02/2021 5 TAINA MELO DELLA PONTA UNIFAJ JAGUARIUNA 6 VALDENICE QUIEZI GONÇALVES FAM AMERICANA O Município de Nova Odessa, torna público a SUSPENSÃO da licitação Tomada MONIQUE QUIEZI GONÇALVES FAM AMERICANA de Preços nº. 02/TP/2021, cujo objeto é OBRA - INFRAESTRUTURA URBANA 7 - EXECUÇÃO DE CALÇADAS NOS BAIRROS JARDIM MARIA HELENA E 8 BRUNA CAROLINA PASCUALI FAM AMERICANA SANTA RITA - NOVA ODESSA/SP. Em decorrência de interesse público. Informa- 9 LUCAS DEMETRIOS LEITE UNISAL AMERICANA ções poderão ser obtidas através do telefone (19) 3476.8602. 10 ESTER GABRIELA GUEDES UNIP CAMPINAS Nova odessa, 23 de agosto de 2021 11 LETICIA SILVA HATSCHBACH DE LIMA UNISAL AMERICANA MIRIAM CECÍLIA LARA NETTO 12 JOANA FELICIANO JATOBA ANHANGUERA SUMARE Secretária de Obras, Projetos e Planejamento Urbano 13 ISABELLA DA SILVA NOCHELLI UNIP LIMEIRA AVISO DE REABERTURA DE TOMADA DE PREÇOS 14 LUCAS EDUARDO SELEBER UNISAL AMERICANA 02/2021 15 KAUA DE OLIVEIRA GONÇALVES SENAI AMERICANA 16 CAROLINE DE O. DOS SANTOS SILVA COTIL LIMEIRA O Município de Nova Odessa, torna público a REABERTURA do edital de licitação 17 MARIA EDUARDA D. LIMA DE OLIVEIRA ETC AMARICANA Tomada de Preços nº. 02/TP/2021, cujo objeto é OBRA - INFRAESTRUTURA UR- 18 ANA LUIZA RAMOS OLIVEIRA ESALC PIRACICABA BANA - EXECUÇÃO DE CALÇADAS NOS BAIRROS JARDIM MARIA HELE- 19 ARTHUR LUCIANO VARANDA DA SILVA FAM AMERICANA NA E SANTA RITA - NOVA ODESSA/SP. -

Unidades De IPORANGA IGUAPE ITAPIRAPUA PAULISTA RIBEIRA ITAOCA Divisão Municipal Alambiques PARIQUERA-ACU CAJATI JACUPIRANGA

Distribuição Espacial de Alambiques, 2007/2008 OUROESTE POPULINA INDIAPORA MESOPOLIS MIRA ESTRELA SANTA ALBERTINA RIOLANDIA RIFAINA SANTA CLARA D OESTE PARANAPUA GUARANI DO OESTE CARDOSO PAULO DE FARIA IGARAPAVA TURMALINA SANTA RITA DO OESTE MACEDONIA DOLCINOPOLIS ARAMINA URANIA FERNANDOPOLIS PONTES GESTAL RUBINEIA ASPASIA MIGUELOPOLIS VITORIA BRASIL ORINDIUVA BURITIZAL PEDRANOPOLIS PEDREGULHO SANTA FE DO SULSANTANA DA PONTE PENSA VOTUPORANGA SANTA SALETE ESTRELA DO OESTE TRES FRONTEIRAS FERNANDOPOLIS COLOMBIA JALES PARISIALVARES FLORENCE AMERICO DE CAMPOS PALESTINA GUAIRA ITUVERAVA JALES JERIQUARA NOVA CANAA PAULISTA SAO FRANCISCO ICEM GUARACI CRISTAIS PAULISTA ILHA SOLTEIRA SAO JOAO DAS DUAS PONTES MERIDIANO VALENTIM GENTIL IPUA PALMEIRA DO OESTE COSMORAMA RIBEIRAO CORRENTE DIRCE REISPONTALINDA VOTUPORANGA SUZANAPOLISAPARECIDA DO OESTE NOVA GRANADA GUARA MARINOPOLIS ORLANDIA BARRETOS SAO JOAO DE IRACEMA TANABI ALTAIR SAO JOAQUIM DA BARRA FRANCA ITAPURA MAGDA MIRASSOLANDIA SAO JOSE DA BELA VISTA ONDA VERDE GUZOLANDIA GENERAL SALGADO SEBASTIANOPOLIS DO SUL BARRETOS AURIFLAMA IPIGUA FLOREAL JABORANDI RESTINGA ITIRAPUA PEREIRA BARRETO SUD MENNUCCI NHANDEARA MORRO AGUDO BALSAMO OLIMPIA ORLANDIA NUPORANGA GENERAL SALGADO MONTE APRAZIVEL POLONI GUAPIACU COLINA PATROCINIO PAULISTA NOVA CASTILHO TERRA ROXA SAO JOSE DO RIO PRETO SEVERINIA FRANCA GASTAO VIDIGAL ANDRADINA MACAUBAL MIRASSOL SALES OLIVEIRA SANTO ANTONIO DO ARACANGUA NOVA LUSITANIA MONCOES NEVES PAULISTA BATATAIS CAJOBI VIRADOURO CASTILHO UNIAO PAULISTA NIPOA CEDRAL MONTE AZUL PAULISTA