Operatic Terminology the Words of an Opera Are Known As the Libretto (Literally "Little Book")

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moniuszko Was Poland’S Leading Nineteenth-Century Opera Composer, and Has Been Called the Man Who Bridges the Gap Between Chopin and Szymanowski

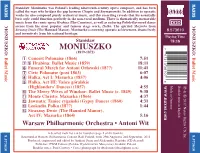

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Stanisław Moniuszko was Poland’s leading nineteenth-century opera composer, and has been called the man who bridges the gap between Chopin and Szymanowski. In addition to operatic works he also composed purely orchestral music, and this recording reveals that his essentially lyric style could function perfectly in the non-vocal medium. There is thematically memorable music from the comic opera Hrabina (The Countess), as well as enduring Polish-flavoured dance DDD MONIUSZKO: scenes from his most popular and famous stage work, Halka. The spirited Mazurka from MONIUSZKO: Straszny Dwór (The Haunted Manor), Moniuszko’s crowning operatic achievement, draws freely 8.573610 and inventively from his national heritage. Playing Time Stanisław 78:18 MONIUSZKO 7 (1819-1872) 47313 36107 Ballet Music 1 Concert Polonaise (1866) 7:51 Ballet Music 2-5 Hrabina: Ballet Music (1859) 18:11 6 Funeral March for Antoni Orłowski (18??) 11:41 7 Civic Polonaise (post 1863) 6:07 8 Halka, Act I: Mazurka (1857) 4:06 9 Halka, Act III: Tańce góralskie 6 (Highlanders’ Dances) (1857) 4:55 www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 0 The Merry Wives of Windsor: Ballet Music (c. 1849) 9:38 & Ꭿ ! Monte Christo: Mazurka (1866) 4:37 2017 Naxos Rights US, Inc. @ Jawnuta: Taniec cygański (Gypsy Dance) (1860) 4:31 # Leokadia Polka (18??) 1:44 $ Straszny Dwór (The Haunted Manor), Act IV: Mazurka (1864) 5:16 Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit A detailed track list can be found on page 2 of the booklet. 8.573610 8.573610 Recorded at Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall, Poland, from 29th August to 2nd September, 2011 Produced, engineered and edited by Andrzej Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko (CD Accord) Publisher: PWM Edition (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne), Kraków, Poland Booklet notes: Paul Conway • Cover photograph by dzalcman (iStockphoto.com). -

Now We Are 126! Highlights of Our 3 125Th Anniversary

Issue 5 School logo Sept 2006 Inside this issue: Recent Visits 2 Now We Are 126! Highlights of our 3 125th Anniversary Alumni profiles 4 School News 6 Recent News of 8 Former Students Messages from 9 Alumni Noticeboard 10 Fundraising 11 A lot can happen in 12 just one year In Memoriam 14 Forthcoming 16 Performances Kim Begley, Deborah Hawksley, Robert Hayward, Gweneth-Ann Jeffers, Ian Kennedy, Celeste Lazarenko, Louise Mott, Anne-Marie Owens, Rudolf Piernay, Sarah Redgwick, Tim Robinson, Victoria Simmons, Mark Stone, David Stout, Adrian Thompson and Julie Unwin (in alphabetical order) performing Serenade to Music by Ralph Vaughan Williams at the Guildhall on Founders’ Day, 27 September 2005 Since its founding in 1880, the Guildhall School has stood as a vibrant showcase for the City of London's commitment to education and the arts. To celebrate the School's 125th anniversary, an ambitious programme spanning 18 months of activity began in January 2005. British premières, international tours, special exhibits, key conferences, unique events and new publications have all played a part in the celebrations. The anniversary year has also seen a range of new and exciting partnerships, lectures and masterclasses, and several gala events have been hosted, featuring some of the Guildhall School's illustrious alumni. For details of the other highlights of the year, turn to page 3 Priority booking for members of the Guildhall Circle Members of the Guildhall Circle are able to book tickets, by post, prior to their going on sale to the public. Below are the priority booking dates for the Autumn productions (see back cover for further show information). -

SEPTEMBER 2009 LIST See Inside for Valid Dates

tel 0115 982 7500 fax 0115 982 7020 SEPTEMBER 2009 LIST See inside for valid dates Dear Customer This month, the record labels get back to the serious business of high profile new releases and we offer them all at our usual attractive prices! The much anticipated Brahms Symphonies with the Berlin Phil & Rattle on EMI are finally released & we can highly recommend them - superb playing and sparkling yet ‘natural’ interpretations. A delight. You want the big names? Jonas Kaufmann, Nicola Benedetti, Renee Fleming, Marcello Alvarez & Mitsuko Uchida all make their appearance on Universal labels. Brendel’s digitally recorded Beethoven Sonatas from the 1990s at last becomes available at a sensible price. EMI wheel out the big guns including Villazon, Pape & Pappano in Verdi’s Messe da Requiem along with Sarah Chang performing the Brahms & Bruch Violin Concerti. We also very much like the Brahms Piano Quintet & Quartet no. 1 with the Quatuor Ebene. Hyperion give us Angela Hewitt performing Handel & Haydn and vol 12 of the Byrd Edition with Cardinall’s Musik whilst ECM follow up their highly recommended Schiff Bach series with the Six Partitas. Our special offers are many & varied. We have the whole Hyperion catalogue reduced, along with Channel Classics, Telarc, full-price Harmonia Mundi titles, Alto, NMC, Svetlanov & Toccata. We also make available a large range of EMI Box Sets, their ’Very Best Of’ series & the Nigel Kennedy catalogue, all at significant reduced prices. Something for everyone. Enjoy perusing the list & we look forward to supplying your classical requirements. Mark, Richard & Mike DON’T FORGET - UK Carriage is FREE over £30 Chandos offer now extended! The reductions on Chandos titles now apply until Friday 25th September, including the multibuy offer of only £8.95 each on full-price single discs! Offers still available from our AUGUST 2009 list (until Friday, 25 September, 2009) Universal Classics Mendelssohn & Purcell titles, & selected DG ‘Originals’ recordings….. -

Grand Finals Concert

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Metropolitan Opera Carlo Rizzi National Council Auditions host Grand Finals Concert Anthony Roth Costanzo Sunday, March 31, 2019 3:00 PM guest artist Christian Van Horn Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Carlo Rizzi host Anthony Roth Costanzo guest artist Christian Van Horn “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser (Wagner) Meghan Kasanders, Soprano “Fra poco a me ricovero … Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali” from Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti) Dashuai Chen, Tenor “Oh! quante volte, oh! quante” from I Capuleti e i Montecchi (Bellini) Elena Villalón, Soprano “Kuda, kuda, kuda vy udalilis” (Lenski’s Aria) from Today’s concert is Eugene Onegin (Tchaikovsky) being recorded for Miles Mykkanen, Tenor future broadcast “Addio, addio, o miei sospiri” from Orfeo ed Euridice (Gluck) over many public Michaela Wolz, Mezzo-Soprano radio stations. Please check “Seul sur la terre” from Dom Sébastien (Donizetti) local listings. Piotr Buszewski, Tenor Sunday, March 31, 2019, 3:00PM “Captain Ahab? I must speak with you” from Moby Dick (Jake Heggie) Thomas Glass, Baritone “Don Ottavio, son morta! ... Or sai chi l’onore” from Don Giovanni (Mozart) Alaysha Fox, Soprano “Sorge infausta una procella” from Orlando (Handel) -

Cinema Ritrovato Di Gian Luca Farinelli, Vittorio Martinelli, Nicola Mazzanti, Mark-Paul Meyer, Ruud Visschedijk

Cinema Ritrovato di Gian Luca Farinelli, Vittorio Martinelli, Nicola Mazzanti, Mark-Paul Meyer, Ruud Visschedijk Iniziamo dalla foto che abbiamo scelto per il manifesto, perché è un’immagine rivelatrice dell’identità di questo festival. Ad un primo sguardo non suscita un interesse particolare. È la foto di scena di un film qualsiasi prodotto in un periodo in cui di cinema se ne faceva tanto, un’immagine come tante. Però se la guardiamo meglio vediamo che al centro della foto c’è uno dei grandi attori del cinema italiano, Aldo Fabrizi, il Don Pietro di Roma città aperta, alle prese con la giustizia. Ci accorgiamo anche che il set è il lato sud di Piazza Maggiore; si scorgono il Palazzo del Podestà, San Petronio, il Nettuno, Palazzo de’ Banchi. L’immagine inizia a intrigarci. Siccome il cinema italiano è da sempre fortemente romano, pochissimi sono stati i film girati a Bologna, almeno sino agli anni ’60. Ecco perché Hanno rubato un tram, il film da cui abbiamo sottratto quest’immagine, è una vera scoperta che ci giunge dal passato. Nonostante si tratti di una piccola produzione, di un film modesto, di cui all’epoca nessuno si accorse, poterlo vedere oggi è un’esperienza straordinaria perché ci porta nella Bologna di quarantasei anni fa e ci fa sentire tutta la distanza del tempo, le dimensioni della trasformazione, l’ampiezza dei cambiamenti, esperienza tanto più forte perché si tratta di immagini inaspettate di un film dimenticabile, che nessuno vedeva più da decenni. Il film è anche un curioso incontro tra generazioni diverse del cinema italiano. -

Apocalypticism in Wagner's Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York

Title Page Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York University, 2015 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Woodrow Steinken It was defended on March 23, 2021 and approved by James Cassaro, Professor, Music Adriana Helbig, Associate Professor, Music David Levin, Professor, Germanic Studies Dan Wang, Assistant Professor, Music Dissertation Director: Olivia Bloechl Professor, Music ii Copyright © by Woodrow Steinken 2021 iii Abstract Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring Woodrow Steinken, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation traces the history of apocalypticism, broadly conceived, and its realization on the operatic stage by Richard Wagner and those who have adapted his works since the late nineteenth century. I argue that Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), presents colloquial conceptions of time, space, and nature via supernatural, divine characters who often frame the world in terms of non-rational metaphysics. Primary among these minor roles is Erda, the personification of the primordial earth. Erda’s character prophesies the end of the world in Das Rheingold, a prophecy undone later in Siegfried by Erda’s primary interlocutor and chief of the gods, Wotan. I argue that Erda’s role changes in various stage productions of the Ring, and these changes bespeak a shifting attachment between humanity, the earth, and its imagined apocalyptic demise. -

Opera Wrocławska

OPERA WROCŁAWSKA ~ INSTYTUCJA KULTURY SAMORZĄDU WOJEWÓDZTWA DOLNOSLĄSKIEGO WSPÓŁPROWADZONA PRZEZ MINISTRA KULTURY I DZIEDZICTWA NARODOWEGO EWA MICHNIK DYREKTOR NAUELNY I ARTYSTYUNY STRASZNY DWÓR THE HAUNTED MANOR STANISŁAW MONIUSZKO OPERA W 4 AKTACH I OPERA IN 4 ACTS JAN CHĘCIŃSKI LIBR ETIO WARSZAWA, 1865 PRAPREMIERA I PREVIEW SPEKTAKLE PREMIEROWE I PREMIERES 00 PT I FR 6 111 2009 I 19 SO I SA 7 Ili 2009 I 19 00 00 ND I SU 8 Ili 2009 117 CZAS TRWANIA SPEKTAKLU 180 MIN. I DURATION 180 MIN . 1 PRZERWA I 1 PAUSE SPEKTAKL WYKONYWANY JEST W JĘZYKU POLSKIM Z POLSKIMI NAPISAMI POLI SH LANGUAGE VERSION WITH SURTITLES STRASZNY DWÓR I THE HAU~TED MAl\ OR REALIZATO RZY I PRODUCERS OBSADA I CAST REALIZATORZY I PROOUCERS MIECZNIK MACIEJ TOMASZ SZREDER ZBIGNIEW KRYCZKA JAROSŁAW BODAKOWSKI KIEROWNICTWO MUZYCZNE, DYRYGENT I MUSICAL DIRECTION, CONDUCTOR BOGUSŁAW SZYNALSKI* JACEK JASKUŁA LACO ADAMIK STEFAN SKOŁUBA INSCENIZACJA I REŻYSERIA I STAGE DIRECTION RAFAŁ BARTMIŃSKI* WIKTOR GORELIKOW ARNOLD RUTKOWSKI* RADOSŁAW ŻUKOWSKI BARBARA KĘDZIERSKA ALEKSANDER ZUCHOWICZ* SCENOGRAFIA I SET & COSTUME DESIGNS DAMAZY ZBIGNIEW ANDRZEJ KALININ MAGDALENA TESŁAWSKA, PAWEŁ GRABARCZYK DAMIAN KONIECZEK KAROL KOZŁOWSKI WSPÓŁPRACA SCENOGRAFICZNA I SET & COSTUME DE SIGNS CO-OPERATION TOMASZ RUDNICKI EDWARD KULCZYK RAFAŁ MAJZNER HENRYK KONWIŃSKI HANNA CHOREOGRAFIA I CHOREOGRAPHY EWA CZERMAK STARSZA NIEWIASTA ALEKSANDRA KUBAS JOLANTA GÓRECKA MAŁGORZATA ORAWSKA JOANNA MOSKOWICZ PRZYGOTOWANIE CHÓRU I CHORUS MASTER MARTA JADWIGA URSZULA CZUPRYŃSKA BOGUMIŁ PALEWICZ ANNA BERNACKA REŻYSERIA ŚWIATEŁ I LIGHTING DESIGNS DOROT A DUTKOWSKA GRZEŚ PIOTR BUNZLER HANNA MARASZ CZEŚNIKOWA ASYSTENT REŻYS ERA I ASS ISTAN T TO THE STAGE DIRECTOR BARBARA BAGIŃSKA SOLIŚCI, ORKIESTRA, CHÓR I BALET ELŻBIETA KACZMARZYK-JANCZAK OPERY WROCŁAWSKIEJ, STATYŚCI ADAM FRONTCZAK, JULIAN ŻYCHOWICZ ALEKSANDRA LEMISZKA SOLOISTS, ORCHESTRA, CHOIR AND BALLET INSPICJENCI I SRTAGE MANAGERS OF THE WROCŁAW OPERA, SUPERNUMERARIES * gościnnie I spec1al guest Dyrekcja zastrzega sobie prawo do zmian w obsadach . -

2015 Hidden Disunities and Uncanny Resemblances

Hidden Disunities and Uncanny Resemblances: Connections and ANGOR UNIVERSITY Disconnections in the Music of Lera Auerbach and Michael Nyman ap Sion, P.E. Contemporary Music Review DOI: 10.1080/07494467.2014.959275 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 27/10/2014 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): ap Sion, P. E. (2014). Hidden Disunities and Uncanny Resemblances: Connections and Disconnections in the Music of Lera Auerbach and Michael Nyman. Contemporary Music Review, 33(2), 167-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2014.959275 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 30. Sep. 2021 Hidden Disunities and Uncanny Resemblances: Connections and Disconnections in the music of Lera -

Michael Nyman

EFFET L OO P SUR... Michael Nyman Michael Nyman (Photo : X.D.R) « Michael Nyman a apparemment découvert comment avoir un pied dans le 18 ème siècle et un autre dans le 20 ème siècle » (Peter Greenaway in Daniel Caux : Peter Greenaway - Editions Dis Voir - 1987) BLABLA Michael Nyman Nationalité : Britannique Naissance : 23 mars 1944 à Londres 1er métier : critique musical Autres : Musicologue, ethno-musicologue, pianiste, claveciniste, compositeur, arrangeur, chef d’orchestre, librettiste, photographe, éditeur …. Signe particulier : Minimaliste Fan de : Henry Purcell Violon d’Ingres : Les musiques de films Michael Nyman (Photo : X.D.R) DU CRITIQUE MUSICAL AU COMPOSITEUR ichael Nyman a étudié le piano et le clavecin au Royal College of Music et au King’s College. A cette époque, il compose déjà mais en 1964, il décide de mettre de côté l’écriture Mmusicale pour travailler en tant que musicologue puis par la suite, il devient critique musical. Ses articles se retrouvent dans des revues comme The Listener, The Spectator... Durant cette période, le monde de la musique contemporaine est fortement imprégné par des compositeurs comme Boulez, Stockhausen, Xenakis… À travers ses articles, Michael Nyman choisit de mettre en lumière des courants musicaux émergents. Dans le même temps, il n’hésite pas à consacrer ses analyses musicales à des genres autres que le classique : le rock, la musique indienne… Cet éclectisme l’amènera plus tard à jouer et composer avec des musiciens issus de divers horizons musicaux. Ainsi, dans le courant des années 1970, il collabore tour à tour avec le groupe de rock anglais The Flying Lizards1, avec le mandoliniste indien U.Shrinivas ou bien encore avec sa compatriote Kate Bush2. -

01-28-2019 Iolanta Eve.Indd

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY iolanta AND BÉLA BARTÓK bluebeard’s castle conductor Iolanta Henrik Nánási Opera in one act production Libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky, Mariusz Treli ´nski based on the play King René’s Daughter set designer by Henrik Hertz Boris Kudliˇcka Bluebeard’s Castle costume designer Marek Adamski Opera in one act lighting designer Libretto by Béla Balázs, based on the Marc Heinz fairy tale by Charles Perrault projection designer Monday, January 28, 2019 Bartek Macias 7:30–10:40 PM sound designer Mark Grey choreographer Tomasz Jan Wygoda The productions of Iolanta and Bluebeard’s Castle dramaturg were made possible by a generous gift from Piotr Gruszczy ´nski Ambassador and Mrs. Nicholas F. Taubman Additional funding was received from Mrs. Veronica Atkins; Dr. Magdalena Berenyi, in memory of Dr. Kalman Berenyi; and the general manager Peter Gelb National Endowment for the Arts jeanette lerman-neubauer Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin Teatr Wielki–Polish National Opera 2018–19 SEASON The ninth Metropolitan Opera performance of PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY’S iolanta conductor Henrik Nánási in order of vocal appearance martha duke robert Larissa Diadkova Alexey Markov iol anta count got tfried vaudémont Sonya Yoncheva Matthew Polenzani brigit ta Ashley Emerson* l aur a Megan Marino bertr and Harold Wilson alméric Mark Schowalter king rené Vitalij Kowaljow ibn-hakia Elchin Azizov Monday, January 28, 2019, 7:30–10:40PM 2018–19 SEASON The 33rd Metropolitan Opera performance of BÉLA BARTÓK’S bluebeard’s castle conductor Henrik Nánási cast judith Angela Denoke duke bluebe ard Gerald Finley * Graduate of the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program Monday, January 28, 2019, 7:30–10:40PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA A scene from Bartók’s Chorus Master (Iolanta) Donald Palumbo Bluebeard’s Castle Musical Preparation (Iolanta) Linda Hall, J. -

![Proceedings [Eng]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4148/proceedings-eng-1414148.webp)

Proceedings [Eng]

2 Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development THEORY AND PRAXIS OF DEVELOPMENT PROCEEDINGS OF THE ONE-DAY SEMINAR1 ON THE OCCASION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE ENCYCLICAL LETTER CARITAS IN VERITATE BY POPE BENEDICT XVI Casina Pio IV, Vatican City State, 3rd December 2019 1 The booklet contains keynote addresses and responses made during the one-day seminar and made available to the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development for publication. 3 Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development Palazzo San Calisto 00120 Vatican City State [email protected] www.humandevelopment.va © 2019 Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD p. 9 H. Em. Card. Peter K. A. TURKSON Prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development OPENING SESSION p. 11 H. Exc. Archbp. Paul Richard GALLAGHER Secretary for Relations with States, Secretariat of State Opening Remarks H. Em. Card. Peter K. A. TURKSON Prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development Introduction H. Exc. Archbp. Silvano M. TOMASI Founder of the Caritas in Veritate Foundation Stefano ZAMAGNI President of PASS La Caritas in Veritate dieci anni dopo THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE CHURCH p. 39 Stefano ZAMAGNI President of PASS When economy divorces from fraternity: The message of Caritas in veritate H. Em Card. Michael CZERNY Undersecretary of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development – Migrants and Refugees Section The message of integral human development and integral ecology: towards Laudato Si’ Msgr. Peter SCHALLENBERG Catholic Central Institute for Social Sciences in Mönchengladbach – Germany The Basis of Personal and Social Ethics for an Integral Human Development 5 THE PERSPECTIVE OF CATHOLIC DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES p. -

Regia E Vita. L'archivio Di Luca Ronconi

Soprintendenza archivistica e bibliografica dell’Umbria e delle Marche Regia e vita. L’archivio di Luca Ronconi Inventario a cura di Rossella Santolamazza Perugia, settembre 2017 Ringraziamenti La curatrice ringrazia il soprintendente Mario Squadroni per l’incarico conferitole. Ringrazia, inoltre, Roberta Carlotto, proprietaria dell’archivio, per aver permesso il riordinamento e l’inventariazione del fondo e per il sostegno garantito nel corso del lavoro. Sostegno garantito anche da Claudia di Giacomo ed Elisa Ragni, cui si estendono i ringraziamenti. Ringrazia, infine, Alessandro Bianchi e Simonetta Laudenzi, funzionari della Soprintendenza archivistica e bibliografica dell’Umbria e delle Marche, per aver, rispettivamente, fotografato gli oggetti in fase di riordinamento e contribuito al riordinamento di alcune buste di documentazione della serie Carteggio personale e contabile e Leonardo Musci e Stefano Vitali per i consigli. Nel frontespizio: Fotografie di Luca Ronconi conservate nell’archivio In alto a sinistra: ASPG, ALR, Attività giovanile, b. 1, fasc. 11, sottofasc. 1; a destra: Ivi, sottofasc. 2. In basso a sinistra: ASPG, ALR, Regie, Documentazione non attribuita, b. 67, fasc. 3, sottofasc. 4; a destra: Ivi, sottofasc. 6. In ultima pagina: Fotografia del premio Lingotto ’90: Gli ultimi giorni dell’umanità, ASPG, ALR, Premi, b. 89, fasc. 19. ISBN 9788895436579 © 2017 - Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo. Soprintendenza archivistica e bibliografica dell’Umbria e delle Marche 2 PRINCIPALI SIGLE ED ABBREVIAZIONI