Impacts of COVID-19 on Animals in Zoos: a Longitudinal Multi-Species Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

Reproductive Seasonality in Captive Wild Ruminants: Implications for Biogeographical Adaptation, Photoperiodic Control, and Life History

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Reproductive seasonality in captive wild ruminants: implications for biogeographical adaptation, photoperiodic control, and life history Zerbe, Philipp Abstract: Zur quantitativen Beschreibung der Reproduktionsmuster wurden Daten von 110 Wildwiederkäuer- arten aus Zoos der gemässigten Zone verwendet (dabei wurde die Anzahl Tage, an denen 80% aller Geburten stattfanden, als Geburtenpeak-Breite [BPB] definiert). Diese Muster wurden mit verschiede- nen biologischen Charakteristika verknüpft und mit denen von freilebenden Tieren verglichen. Der Bre- itengrad des natürlichen Verbreitungsgebietes korreliert stark mit dem in Menschenobhut beobachteten BPB. Nur 11% der Spezies wechselten ihr reproduktives Muster zwischen Wildnis und Gefangenschaft, wobei für saisonale Spezies die errechnete Tageslichtlänge zum Zeitpunkt der Konzeption für freilebende und in Menschenobhut gehaltene Populationen gleich war. Reproduktive Saisonalität erklärt zusätzliche Varianzen im Verhältnis von Körpergewicht und Tragzeit, wobei saisonalere Spezies für ihr Körpergewicht eine kürzere Tragzeit aufweisen. Rückschliessend ist festzuhalten, dass Photoperiodik, speziell die abso- lute Tageslichtlänge, genetisch fixierter Auslöser für die Fortpflanzung ist, und dass die Plastizität der Tragzeit unterstützend auf die erfolgreiche Verbreitung der Wiederkäuer in höheren Breitengraden wirkte. A dataset on 110 wild ruminant species kept in captivity in temperate-zone zoos was used to describe their reproductive patterns quantitatively (determining the birth peak breadth BPB as the number of days in which 80% of all births occur); then this pattern was linked to various biological characteristics, and compared with free-ranging animals. Globally, latitude of natural origin highly correlates with BPB observed in captivity, with species being more seasonal originating from higher latitudes. -

For Review Only 440 IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group

Manuscripts submitted to Journal of Mammalogy A Pliocene hybridisation event reconciles incongruent mitochondrial and nuclear gene trees among spiral-horned antelopes Journal:For Journal Review of Mammalogy Only Manuscript ID Draft Manuscript Type: Feature Article Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Rakotoarivelo, Andrinajoro; University of Venda, Department of Zoology O'Donoghue, Paul; Specialist Wildlife Services, Specialist Wildlife Services Bruford, Michael; Cardiff University, Cardiff School of Biosciences Moodley, Yoshan; University of Venda, Department of Zoology adaptive radiation, interspecific hybridisation, paleoclimate, Sub-Saharan Keywords: Africa, Tragelaphus https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jmamm Page 1 of 34 Manuscripts submitted to Journal of Mammalogy 1 Yoshan Moodley, Department of Zoology, University of Venda, 2 [email protected] 3 Interspecific hybridization in Tragelaphus 4 A Pliocene hybridisation event reconciles incongruent mitochondrial and nuclear gene 5 trees among spiral-horned antelopes 6 ANDRINAJORO R. RAKATOARIVELO, PAUL O’DONOGHUE, MICHAEL W. BRUFORD, AND * 7 YOSHAN MOODLEY 8 Department of Zoology, University of Venda, University Road, Thohoyandou 0950, Republic 9 of South Africa (ARR, ForYM) Review Only 10 Specialist Wildlife Services, 102 Bowen Court, St Asaph, LL17 0JE, United Kingdom (PO) 11 Cardiff School of Biosciences, Sir Martin Evans Building, Cardiff University, Museum 12 Avenue, Cardiff, CF10 3AX, United Kingdom (MWB) 13 Natiora Ahy Madagasikara, Lot IIU57K Bis, Ampahibe, Antananarivo 101, Madagascar 14 (ARR) 15 16 1 https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jmamm Manuscripts submitted to Journal of Mammalogy Page 2 of 34 17 ABSTRACT 18 The spiral-horned antelopes (Genus Tragelaphus) are among the most phenotypically diverse 19 of all large mammals, and evolved in Africa during an adaptive radiation that began in the late 20 Miocene, around 6 million years ago. -

Bale-Travel-Guidebook-Web.Pdf

Published in 2013 by the Frankfurt Zoological Society and the Bale Mountains National Park with financial assistance from the European Union. Copyright © 2013 the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority (EWCA). Reproduction of this booklet and/or any part thereof, by any means, is not allowed without prior permission from the copyright holders. Written and edited by: Eliza Richman and Biniyam Admassu Reader and contributor: Thadaigh Baggallay Photograph Credits: We would like to thank the following photographers for the generous donation of their photographs: • Brian Barbre (juniper woodlands, p. 13; giant lobelia, p. 14; olive baboon, p. 75) • Delphin Ruche (photos credited on photo) • John Mason (lion, p. 75) • Ludwig Siege (Prince Ruspoli’s turaco, p. 36; giant forest hog, p. 75) • Martin Harvey (photos credited on photo) • Hakan Pohlstrand (Abyssinian ground hornbill, p. 12; yellow-fronted parrot, Abyssinian longclaw, Abyssinian catbird and black-headed siskin, p. 25; Menelik’s bushbuck, p. 42; grey duiker, common jackal and spotted hyena, p. 74) • Rebecca Jackrel (photos credited on photo) • Thierry Grobet (Ethiopian wolf on sanetti road, p. 5; serval, p. 74) • Vincent Munier (photos credited on photo) • Will Burrard-Lucas (photos credited on photo) • Thadaigh Baggallay (Baskets, p. 4; hydrology photos, p. 19; chameleon, frog, p. 27; frog, p. 27; Sof-Omar, p. 34; honey collector, p. 43; trout fisherman, p. 49; Finch Habera waterfall, p. 50) • Eliza Richman (ambesha and gomen, buna bowetet, p. 5; Bale monkey, p. 17; Spot-breasted plover, p. 25; coffee collector, p. 44; Barre woman, p. 48; waterfall, p. 49; Gushuralle trail, p. 51; Dire Sheik Hussein shrine, Sof-Omar cave, p. -

Nyala ... Antelope That Love to Strut Their Stuff! GIRAFFE TAG

ANTELOPE AND Nyala ... antelope that love to strut their stuff! GIRAFFE TAG Why exhibit nyala? • Get two animals in one! In this striking sexually dimorphic species, the sleek, brilliantly-striped females contrast sharply with the shaggy, dark gray males with impressive spiraling horns. • Entrance visitors with showmanship: during courtship or when just feeling confident, males raise their spectacular dorsal crest, increasing their apparent size while they strut around. • Help the SSP by holding a bachelor group, and you can have several of these handsome antelope showing off at the same time! • Add interest to existing exhibits: nyala mix well with many species. • Melt the hearts of your guests and light up your social media: nyala breed readily at a young age and produce adorable calves annually. MEASUREMENTS IUCN Stewardship Opportunities Length: 4.5-6.5 feet LEAST Support the mountain nyala, an endangered relative CONCERN Height: 2.5-4 feet of the nyala and in situ TAG focus species: at shoulder MELCA-Ethiopia Weight: 120-275 lbs 32,000 http://www.melcaethiopia.org/ Woodland Southern Africa in the wild Care and Husbandry YELLOW SSP: 56.128 (184) in 16 AZA (+5 non-AZA) institutions (2019) Species coordinator: Steve Metzler, San Diego Zoo Safari Park [email protected] ; (760) 473-6993 Social nature: Herd-living. Females usually kept in groups with/without a single breeding male. Multiple males can be housed together in bachelor groups (how many depends on space and management). Mixed species: Mix well with a wide variety of ground birds and hoofstock. Breeding males may show aggression to other male ungulates. -

Tragelaphus Spekii

ORIGINAL COMMUNICATION Anatomy Journal of Africa. 2021. Vol 10 (1):1974-1979 GROSS ANATOMICAL STUDIES ON THE HIND LIMB OF THE SITATUNGA (Tragelaphus spekii). Kenechukwu Tobechukwu Onwuama, Sulaiman Olawoye Salami, Esther Solomon Kigir, Alhaji Zubair Jaji Department of Veterinary Anatomy, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria Abbreviated title: Hind limb bones of the Sitatunga Corresponding address: Kenechukwu Tobechukwu Onwuama. Telephone number: 08036425961. E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Sitatunga, Tragelaphus spekii, is a swamp dwelling antelope resident in West Africa. This study was carried out to document unique morphological and numerical information on the hind limb bones of this ruminant. Two (2) adults of both sexes were obtained as carcass at different times after post-mortem examination and prepared to extract the bones via cold water maceration for use in the study. The presence of a sharp pointed ilio-pubic eminence at the junction between the cranial border of the ilium and pubis; less prominent ischial tuber, inconspicuous ischiatic arch and a large oval obturator foramen were unique features of the Ossa coxarum that distinguished it from that of small ruminants. The Femur’s medial condyle was obliquely orientated, the fibula was absent while the long Tibia was typical of ruminant presentation. It was observed that the morphological features of the tarsals and Pes were also typical. However, the last Phalanges presented characteristic long triangular shaped bones with sharp pointed ends. The total number of bones making up the forelimb was accounted to be 45. In conclusion, this study has provided a baseline data for further biological, archeological and comparative anatomical studies. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

How Independence Saved an African Reserve by G

25 How Independence Saved an African Reserve By G. D. Hayes Before 1939 the Lengwe game reserve in Nyasaland sheltered a wide range of large animals, including the rare nyala antelope for whose protection it was originally declared. By the end of the war, with invasions and settlement and large-scale poaching, it hardly qualified as a reserve at aU, says the author, who is honorary secretary of the Fauna Preservation Society of Malawi; and the situation was not much better in 1964 when the country achieved independence as Malawi. Then, thanks to the personal interest of Dr. Banda, a decision to abolish the reserve was reversed and a new water supply installed which has transformed the situation. TpHE latest developments in the Lengwe Game Reserve of Malawi ••• are a perfect demonstration of nature's ability to protect an animal species if given but half a chance. Since the end of the second world war the story of this reserve has been one of continual struggle for survival, and one that has more than once been all but lost. The credit for its survival despite all attempts to abolish it must, to some extent, go to the Fauna Preservation Society of Malawi (formerly the Nyasaland Fauna Preservation Society) with invaluable assistance from the Fauna Preservation Society in London. The Lengwe reserve is in the Chikwawa district of southern Malawi, one of two known as the Lower River districts, and covers some fifty square miles of mixed park-like country, with large, very dense thickets in which the rare nyala antelope Tragelaphus angasii finds sanctuary. -

Black Wildebeest

SSOOUUTTHHEERRNN AAFFRRIICCAANN RRAAPPTTOORR CCOONNSSEERRVVAATTIIOONN STRATEGIC PLANNING WORKSHOP REPORT 23 – 25 March 2004 Gariep Dam, Free State, South Africa Hosted by: THE RAPTOR CONSERVATION GROUP OF THE ENDANGERED WILDLIFE TRUST Sponsored by: SA EAGLE INSURANCE COMPANY ESKOM In collaboration with: THE CONSERVATION BREEDING SPECIALIST GROUP SOUTHERN AFRICA (CBSG – SSC/IUCN) 0 SSOOUUTTHHEERRNN AAFFRRIICCAANN RRAAPPTTOORR CCOONNSSEERRVVAATTIIOONN STRATEGIC PLANNING WORKSHOP REPORT The Raptor Conservation Group wishes to thank Eskom and SA Eagle Insurance company for the sponsorship of this publication and the workshop. Evans, S.W., Jenkins, A., Anderson, M., van Zyl, A., le Roux, J., Oertel, T., Grafton, S., Bernitz Z., Whittington-Jones, C. and Friedmann Y. (editors). 2004. Southern African Raptor Conservation Strategic Plan. Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC / IUCN). Endangered Wildlife Trust. 1 © Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG-SSC/IUCN) and the Endangered Wildlife Trust. The copyright of the report serves to protect the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group workshop process from any unauthorised use. The CBSG, SSC and IUCN encourage the convening of workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believe that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report reflect the issues discussed and ideas expressed by the participants during the Southern African Raptor Conservation Strategic -

Country Profile Republic of Malawi Giraffe Conservation Status Report July 2020

Country Profile Republic of Malawi Giraffe Conservation Status Report July 2020 General statistics Size of country: 118,480 km² Size of protected areas / percentage protected area coverage: 15% Species and subspecies In 2016 the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) completed the first detailed assessment of the conservation status of giraffe, revealing that their numbers are in peril. This was further emphasised when the majority of the IUCN recognised subspecies where assessed in 2018 – some as Critically Endangered. While this update further confirms the real threat to one of Africa’s most charismatic megafauna, it also highlights a rather confusing aspect of giraffe conservation: how many species/subspecies of giraffe are there? The IUCN currently recognises one species (Giraffa camelopardalis) and nine subspecies of giraffe (Muller et al. 2016) historically based on outdated assessments of their morphological features and geographic ranges. The subspecies are thus divided: Angolan giraffe (G. c. angolensis), Kordofan giraffe (G. c. antiquorum), Masai giraffe (G. c. tippleskirchi), Nubian giraffe (G. c. camelopardalis), reticulated giraffe (G. c. reticulata), Rothschild’s giraffe (G. c. rothschildi), South African giraffe (G. c. giraffa), Thornicroft’s giraffe (G. c. thornicrofti) and West African giraffe (G. c. peralta). However, over the past decade GCF together with their partner Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre (BiK-F) have performed the first-ever comprehensive DNA sampling and analysis (genomic, nuclear and mitochondrial) from all major natural populations of giraffe throughout their range in Africa. As a result, an update to the traditional taxonomy now exists. This study revealed that there are four distinct species of giraffe and likely five subspecies (Fennessy et al. -

Abundance and Distribution of Lesser Kudu (Tragelaphus Imberbis, Blyth, 1869) in Tululujia Wildlife Reserve, Southwestern Ethiopia Belete Tilahun

Asian Journal of Applied Science and Technology (AJAST) (Open Access Quarterly International Journal) Volume 1, Issue 9, Pages 481-495, 2017 Abundance and Distribution of Lesser Kudu (Tragelaphus imberbis, Blyth, 1869) in Tululujia Wildlife Reserve, Southwestern Ethiopia Belete Tilahun Department of Wildlife and Ecotourism Management, Wolkite University, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Wolkite, PO Box 07, Ethiopia. Article Received: 30 August 2017 Article Accepted: 29 November 2017 Article Published: 27 December 2017 ABSTRACT Lesser Kudu is commonly distributed in forest and bush-land habitats of eastern and southern lowlands of Ethiopia. However, their numbers are declining much of its previous range, due to illegal hunting and habitat distraction. Even though, the species occur in study area, inadequate information about Lesser Kudu population. This study was aim to assess abundance and distribution of Lesser Kudu in study area. The study was carried out in stratified study area, forest and wooded grassland habitat types based on land cover feature. The transect line sampling method, that was laid in random fashion in each habitat types were used. The estimated population size of Lesser Kudu was 573 individuals in the study site. The population size was higher during wet season than dry season due to birth calves of Lesser Kudu during wet season. Generally, the distribution in the forest habitat (125±4.97SE) was significantly higher than wooded grassland habitat (105±4.83SE). There was 0.99±0.05SE Lesser Kudu per square km in the study area. The populations of Lesser Kudus were composed of 55.47% of females, 30.11% of males and 14.42% of juveniles in the area. -

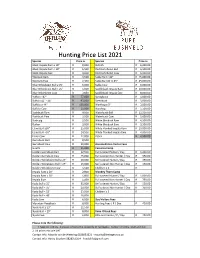

Hunting Price List 2021

Hunting Price List 2021 Species Price in Species Price in Black Impala Ram ≥ 18" R 8,000 Ostrich R 6,000.00 Black Impala Ram < 18" R 6,500 Red Hartebeest Bull R 6,500.00 Black Impala Ewe R 4,000 Red Hartebeest Cow R 6,000.00 Blesbuck Ram R 3,500 Sable Bull < 40" R 15,000.00 Blesbuck Ewe R 2,300 Sable Bull 40 to 45" R 25,000.00 Blue Wildebeest Bull ≥ 25" R 6,000 Sable Cow R 6,000.00 Blue Wildebeest Bull < 25" R 5,000 Saddleback Impala Ram R 10,000.00 Blue Wildebeest Cow R 3,850 Saddleback Impala Ewe R 8,000.00 Buffalo <42" R 77,000 Springbuck R 4,000.00 Buffalo 42" - 44" R 93,000 Steenbuck R 3,000.00 Buffalo ≥ 44" R 150,000 Warthog ≥ 9" R 2,800.00 Buffalo Cow R 15,000 Warthog R 1,500.00 Bushbuck Ram R 9,000 Waterbuck Bull R 12,500.00 Bushbuck Ewe R 3,500 Waterbuck Cow R 5,600.00 Bush pig R 2,500 White Blesbuck Ram R 4,500.00 Duiker R 3,000 White Blesbuck Ewe R 3,500.00 Eland Bull ≥30" R 25,000 White Flanked Impala Ram R 10,000.00 Eland Bull <30" R 14,500 White Flanked Impala Ewe R 4,000.00 Eland Cow R 12,000 Zebra R 4,500.00 Gemsbuck Bull R 8,500 Gemsbuck Cow R 20,000 Accomodation Visitor Fees Giraffe R 15,000 Cussonia Camp Golden Gemsbuck Bull R 12,500 Full catered Hunter / Day R 1,200.00 Golden Gemsbuck Cow R 25,000 Full catered Non Hunter / Day R 950.00 Golden Wildebeest Bull ≥ 27" R 20,000 Self catered Hunter / Day R 750.00 Golden Wildebeest Bull < 27" R 15,000 Self catered Non Hunter / Day R 550.00 Golden Wildebeest Cow R 5,500 Children ≥ 3 R - Impala Ram ≥ 20" R 2,800 Monkey Thorn Camp Impala Ram < 20" R 1,800 Full catered Hunter / Day R 1,000.00 Impala Ewe R 1,400 Full catered Non Hunter / Day R 750.00 Kudu Bull ≥ 55" R 35,000 Self catered Hunter / Day R 550.00 Kudu Bull < 55" R 20,000 Self catered Non Hunter / Day R 350.00 Kudu Bull < 52" R 13,500 Children ≥ 3 R - Kudu Bull < 48" R 10,000 Kudu Cow R 6,500 Day Visitors Fees Mountain Reedbuck R 8,000 Hunting Fees / P / Day R 450.00 Nyala Bull ≥ 25" R 11,500 Nyala Bull < 25" R 8,000 Farm If Used Fees Nyala Ewe R 6,000 Rifle and Ammo / P / Day R 250.00 Please note the following: 1.