Big Me Dan Chaon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

BRIGANCE Readiness Activities for Emerging K Children

BRIGANCE® Readiness Activities for Emerging K Children • Reading • Mathematics • Additional Support for Emerging K ©Curriculum Associates, LLC Click on a title to go directly to that page. Contents Mathematics BRIGANCE Activity Finder Number Concepts ............................ 89 Connecting to i-Ready Next Steps: Reading ...........iii Counting ................................... 98 Connecting to i-Ready Next Steps: Mathematics ........iv Reads Numerals ............................. 104 Additional Support for Emerging K .................. v Numeral Comprehension .......................110 Numerals in Sequence .........................118 Quantitative Concepts ........................ 132 BRIGANCE Readiness Activities Shape Concepts ............................ 147 Reading Joins Sets ................................. 152 Body Parts ................................... 1 Directional/Positional Concepts .................. 155 Colors ..................................... 12 Response to and Experience with Books ............ 21 Additional Support for Emerging K Prehandwriting .............................. 33 General Social and Emotional Development ......... 169 Visual Discrimination .......................... 38 Play Skills and Behaviors ...................... 172 Print Awareness and Concepts ................... 58 Initiative and Engagement Skills and Behaviors ....... 175 Reads Uppercase and Lowercase Letters ............ 60 Self-Regulation Skills and Behaviors ...............177 Prints Uppercase and Lowercase Letters in Sequence .. 66 -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

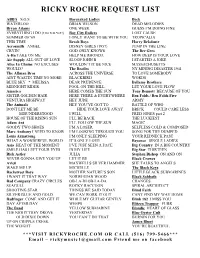

Ricky Roche Request List

RICKY ROCHE REQUEST LIST ABBA S.O.S. Barenaked Ladies Beck WATERLOO BRIAN WILSON DEAD MELODIES Bryan Adams ONE WEEK GUESS I’M DOING FINE EVERYTHING I DO (I DO FOR YOU) Bay City Rollers LOST CAUSE SUMMER OF '69 I ONLY WANT TO BE WITH YOU TROPICALIA THIS TIME Beach Boys Harry Belafonte Aerosmith ANGEL DISNEY GIRLS (1957) JUMP IN THE LINE CRYIN’ GOD ONLY KNOWS The Bee Gees A-Ha TAKE ON ME HELP ME RHONDA HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE Air Supply ALL OUT OF LOVE SLOOP JOHN B I STARTED A JOKE Alice In Chains NO EXCUSES WOULDN’T IT BE NICE MASSACHUSETTS WOULD? The Beatles NY MINING DISASTER 1941 The Allman Bros ACROSS THE UNIVERSE TO LOVE SOMEBODY AINT WASTIN TIME NO MORE BLACKBIRD WORDS BLUE SKY * MELISSA DEAR PRUDENCE Bellamy Brothers MIDNIGHT RIDER FOOL ON THE HILL LET YOUR LOVE FLOW America HERE COMES THE SUN Tony Bennett BECAUSE OF YOU SISTER GOLDEN HAIR HERE THERE & EVERYWHERE Ben Folds / Ben Folds Five VENTURA HIGHWAY HEY JUDE ARMY The Animals HEY YOU’VE GOT TO BATTLE OF WHO DONT LET ME BE HIDE YOUR LOVE AWAY BRICK COULD CARE LESS MISUNDERSTOOD I WILL FRED JONES part 2 HOUSE OF THE RISING SUN I’LL BE BACK THE LUCKIEST Adam Ant I’LL FOLLOW THE SUN MAGIC GOODY TWO SHOES I’M A LOSER SELFLESS COLD & COMPOSED Marc Anthony I NEED TO KNOW I’M LOOKING THROUGH YOU SONG FOR THE DUMPED Louis Armstrong I’M ONLY SLEEPING YOUR REDNECK PAST WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD IT’S ONLY LOVE Beyonce SINGLE LADIES Asia HEAT OF THE MOMENT I’VE JUST SEEN A FACE Big Country IN A BIG COUNTRY SMILE HAS LEFT YOUR EYES IN MY LIFE Big Star THIRTEEN Rick Astley JULIA Stephen Bishop -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

The Indiana State Fair Environment and Traditions Maintained Here at Speedway, in Comparison to His Previous Teaching Positions

Plugged In Issue One • the official school newspaper of Speedway Senior High School • September 18, 2015 Small Town Cliche Observations of life at a small school J O A N N A B E R R Y • Plugged In Reporter In describing the town of Speedway, it’s hard to avoid the cliché that accommodates it – a small town named after the world-famous race track sit- ting on 16th Street. Our school gets the same treat- ment. Expanding on the family-like structure that is so prominent here is easy; avoiding that cursed cliché is not. GETTING BETTER EVERY DAY! The volleyball girls picked up a huge ICC win over Class A powerhouse Lutheran last Tuesday night. Freshman Anna Long and sophomore Mackenzie Smith are gaining valuable experience helping the varsity volleyball Plugs as they prepare to defend their three time sectional To gain input on our school from a non-student championship next month. Photo by Sydney Judge, courtesy of the Champion. point of view, I decided to ask new principal Kyle Trebley what he likes about being the principal at Speedway. A new staff member as of last year, Trebley has had the opportunity to observe the The Indiana State Fair environment and traditions maintained here at Speedway, in comparison to his previous teaching positions. A family tradition reinvented In making the transition from vice principal to Despite classes starting tragically premature, Speedway graduates Megan and Matt Turk, are at principal, he hasn’t noticed any significant changes what traditional summer would be complete without the fair almost every day operating a number of in his interactions with students, albeit a bit more a trip to the State Fair? The first State Fair in Indiana food stands on the grounds. -

Grindstone Song List

GrindStone Song List Artist Song Title 3 Days Grace Just Like You 3 Days Grace Pain 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Not My Time 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 311 / The Cure Love Song 7 Mary Three Cumbersome Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Living On the Edge Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Alice In Chains Man In The Box Alice In Chains Would Alice In Chains Check My Brain Alice In Chains No Excuses Alice In Chains Nutshell Ataris Boys Of Summer Audioslave Like a Stone Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Beastie Boys Fight For Your Right Billy Idol Rebel Yell Billy Joel You May Be Right Black Crowes Hard to Handle Blessed Union of Souls I Believe Blind Melon No Rain/Change Blur Song 2 Bob Segar/Metallica Turn The Page Bon Jovi Blood on Blood Bon Jovi Keep the Faith Bon Jovi Livin’ on a Prayer GrindStone Song List Artist Song Title Bon Jovi Wanted Dead or Alive Bon Jovi You Give Love a Bad Name Breaking Benjamin Breath Breaking Benjamin I Will Not Bow Breaking Benjamin So Cold Bruno Mars Grenade Buck Cherry Crazy Bitch Buck Cherry All Lit Up Buck Cherry Sorry Bush Glycerine Bush Machine Head Cage The Elephant Aint No Rest For the Wicked Cake I Will Survive Candlebox Far Behind Cat Stevens Wild World CCR Bad Moon Rising CCR Have You Even Seen the Rain Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Collective Soul Shine Counting Crowes Mr. Jones Counting Crowes ‘Round Here Cracker Low Creed Higher Creed My Own Prison Creed My Sacrifice Creed What If Creed What’s This Life For Creed With Arms Wide Open Crossfade Cold Danzig Mother Darius -

MOODY Song List 2017

2 PAC FEAT DR DRE – CALIFORNIA LOVE ARETHA FRANKLIN – (YOU MAKE ME FEEL BETTY WRIGHT – TONIGHT IS THE NIGHT 3 DOORS DOWN - HERE WITHOUT YOU LIKE) A NATURAL WOMAN BEYONCE – AT LAST 3 DOORS DOWN - KRYPTONITE ARCHIES – SUGAR, SUGAR BEYONCE – RUDE BOY 3 DOORS DOWN - WHEN I'M GONE AVICII – HEY BROTHER BEYONCE - SINGLE LADIES 4 NON BLONDES – WHAT’S UP AVICII – LEVELS BIG & RICH - SAVE A HORSE, RIDE A 311 - LOVESONG AVICII – WAKE ME UP COWBOY 50 CENT – IN DA CLUB AVRIL LAVIGNE – SK8ER BOI BIG & RICH – LOST IN THIS MOMENT ABBA – DANCING QUEEN AWOLNATION - SAIL BILL WITHERS – AIN’T NO SUNSHINE AC/DC – BACK IN BLACK AUDIOSLAVE - LIKE A STONE BILL WITHERS - USE ME AC/DC - YOU SHOOK ME (ALL NIGHT LONG) B – 52'S LOVE SHACK BILLY HOLIDAY – STORMY WEATHER ACE OF BASE – ALL THAT SHE WANTS B.O.B - NOTHIN ON YOU BILLY IDOL - DANCING WITH MYSELF ADELE – MAKE YOU FEEL YOUR LOVE BAAUER - HARLEM SHAKE BILLIE JOEL - PIANO MAN ADELE – ONE AND ONLY BACKSTREET BOYS - I WANT IT THAT WAY BILLY JOEL - YOU MAY BE RIGHT ADELE - ROLLING IN THE DEEP BAD COMPANY - SHOOTING STAR BILLY RAY CYRUS - ACHY BREAKY HEART ADELE - SET FIRE TO THE RAIN BAD COMPANY – FEEL LIKE MAKING LOVE BILLY THORPE – CHILDREN OF THE SUN ADELE - SOMEONE LIKE YOU BARENAKED LADIES – IF I HAD $100,000,000 BLACK CROWES - HARD TO HANDLE A-HA – TAKE ON ME BASTILLE – BAD BLOOD BLACK CROWES - JEALOUS AGAIN AFGHAN WHIGS - DEBONAIR BASTILLE – POMPEII BLACK CROWES - SHE TALKS TO ANGELS AFROMAN - BECAUSE I GOT HIGH BEACH BOYS – GOD ONLY KNOWS BLACK EYED PEAS – I GOTTA FEELING AFROMAN – CRAZY RAP BEACH BOYS -

A Chronology

Dreamforce Bands A Chronology TRAIN STICK WITH THE ROCK, LOSE THE COUNTRY 2006 Pretty good choice for what is typically considered the first year of DF concerts. At the time Train had not yet come out with "Marry Me" and "Drive By" so we won't penalize for those disasters and "Calling All Angels" had not yet been established as a baseball team theme song. "Drops of Jupiter" is a justifiable hit. INXS BIG HAIR - BIG HITS If you are going to have a year with '80s music, INXS is a great selection. 2007 Plenty of recognizable hits, including "Need You Tonight" (which somehow reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100) and, my favorite (if I were forced to pick one), "Don't Change" FOO FIGHTERS NIRVANA - ONLY BETTER David Grohl took everything that was revolutionary about the Nirvana sound 2008 and made it fun to listen to. Ranging from the Beatle-ish "Big Me" to the Platinum hit "Best of You" the Foo Fighters are arguably the best DF band to date (more on that in a bit). BLACK CROWES JAMMIN' SOUTHERN ROCK 2009 Recently broken up (again), the Black Crowes consistently delivered a great sound beginning with the hit cover of Otis Redding's "Hard to Handle", "Twice as Hard", and the easy to listen to "Thorn in my Pride" STEVIE WONDER MUSIC IS A WORLD WITHIN ITSELF Amazing that it has been 43 years since "Superstition" came out and almost 2010 forty years since the "Songs in the Key of Life" was released. I wish those days would come back once more... -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title DiscID Title DiscID 10 Years 2 Pac & Eric Will Wasteland SC8966-13 Do For Love MM6299-09 10,000 Maniacs 2 Pac & Notorious Big Because The Night SC8113-05 Runnin' SC8858-11 Candy Everybody Wants DK082-04 2 Unlimited Like The Weather MM6066-07 No Limits SF006-05 More Than This SC8390-06 20 Fingers These Are The Days SC8466-14 Short Dick Man SC8746-14 Trouble Me SC8439-03 3 am 100 Proof Aged In Soul Busted MRH10-07 Somebody's Been Sleeping SC8333-09 3 Colours Red 10Cc Beautiful Day SF130-13 Donna SF090-15 3 Days Grace Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 Home SIN0001-04 I'm Mandy SF079-03 Just Like You SIN0012-08 I'm Not In Love SC8417-13 3 Doors Down Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Away From The Sun SC8865-07 Things We Do For Love SFMW832-11 Be Like That MM6345-09 Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Behind Those Eyes SC8924-02 We Do For Love SC8456-15 Citizen Soldier CB30069-14 112 Duck & Run SC3244-03 Come See Me SC8357-10 Here By Me SD4510-02 Cupid SC3015-05 Here Without You SC8905-09 Dance With Me SC8726-09 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) CB30070-01 It's Over Now SC8672-15 Kryptonite SC8765-03 Only You SC8295-04 Landing In London CB30056-13 Peaches & Cream SC3258-02 Let Me Be Myself CB30083-01 Right Here For You PHU0403-04 Let Me Go SC2496-04 U Already Know PHM0505U-07 Live For Today SC3450-06 112 & Ludacris Loser SC8622-03 Hot & Wet PHU0401-02 Road I'm On SC8817-10 12 Gauge Train CB30075-01 Dunkie Butt SC8892-04 When I'm Gone SC8852-11 12 Stones 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Crash TU200-04 Landing In London CB30056-13 Far Away THR0411-16 3 Of A Kind We Are One PHMP1008-08 Baby Cakes EZH038-01 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

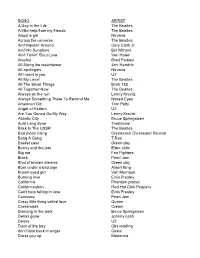

Tommy Strazza Song List 2018

SONG ARTIST A Day in the Life The Beatles A little help from my friends The Beatles About a girl Nirvana Across the universe The Beatles Ain't Messin' Around Gary Clark Jr. Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't Talkin' 'Bout Love Van Halen Alcohol Brad Paisley All Along the watchtower Jimi Hendrix All apologies Nirvana All I want is you U2 All My Lovin' The Beatles All The Small Things Blink 182 All Together Now The Beatles Always on the run Lenny Kravitz Always Something There To Remind Me Naked Eyes American Girl Tom Petty Angel of Harlem U2 Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Atlantic City Bruce Springsteen Auld Lang Syne Traditional Back In The USSR The Beatles Bad moon rising Creedence Clearwater Revival Bang A Gong T.Rex Basket case Green day Benny and the jets Elton John Big me Foo Fighters Black Pearl Jam Blvd of broken dreams Green day Born under a bad sign Albert King Brown eyed girl Van Morrison Burning love Elvis Presley California Phantom planet Californication Red Hot Chili Peppers Can't help falling in love Elvis Presley Corduroy Pearl Jam Crazy little thing called love Queen Crossroads Cream Dancing in the dark Bruce Springsteen Delias gone Johnny cash Desire U2 Dock of the bay Otis redding don’t look back in anger Oasis Dress you up Madonna Elderly Woman behind the counter in a small town Pearl Jam Ever long Foo fighters Every rose has its thorn poison Everyday Dave Matthews band Evil Ways Santana Fake plastic trees radio head Fire and Rain James Taylor Flake Jack Johnson Folsom Prison blues Johnny cash For what its worth