THE SOUL's CONFLICT with ITSELF Richard Sibbes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tttlf SLOP"1 MIRES to » Pwwfl WILL "

m COAL! COAL! For Household Removals Ph«»ne S2) Hall & Walker Burt’s Padded Vans tttlf 123? Government Street 735 PANDORA ST. •rompt Attention Experienced Men TELEPHONE 83. R<. tder.e# Phone R7L0. NO. 27 \ K IX) Kl A, i;. VVEBXEtiDAÏ, AL'U U ST ..... y.ou.ûs. ................... .y TO-OÔY’S BASEBALL SLOP"1 MIRES TO pwwfl WILL NORTHWESTERN LEAGUE xÿjtè -%ï Portland —Pim Inning: Victoria. W'Portland, T. , . " COHOCT LIE Second Inning Victoria, 1; Port be consol» land, 0. Batteries — Thorsen and De Vogt ; Jensen and Bradley. idéflmi\ ’ fmm At Tacoma—First Inning: Vancou WILL BE GENERAL IN LONG LEGAL BATTLE TENDERS FOR HUDSON ver, 0; Tacoma. 0. Second timing Not runs* PROVINCE BY AUGUST 20 ~ HAS BEEN TERMINATED ......BAY RAILWAY OPENED Batteries—Cates and Lewis; Annie ' ( and Slebt. At Seattle—First Inning: Spokane, 0; Seattle. 0. Wheat Reported Fully Headed Contracts Will Soon Be Award Second Inning: No runé. Settlement Means. Much to . Qut—Condition of Oats ed—Work to Start Before__ Third inning; Spokane, 0; Seattle. 1. Camp—Development Wifi Batteries—Bonner. and Spiesman ; and Barley — Bè Actively Carried on 7—— September 1 Fullerton and Shea. Tna+IôNAI. league ' --------- 4 At Cincinnati—Philadelphia-Cincin Regina. Sask . Aug. 2.—That harvest nati game postponed on account of Kelson, B. C.. Aug. 2.—R. S. Lennle, Ottawa. Aug. %- The active pro ing in Saskatchewan will be general Wh.i returned yesterday from Slocan. gramme for the construction of the At Chicago— R. H- E. by- August 20 la the announcement made announcement of the consolida Hudson May Railway will be made Im Brooklyn ....rrrr. -

What Should I Put in the Recycling Bin?

MÙ« ϤϢϣϨ REDLANDS MODERN COUNTRY MUSIC CLUB NewsleƩer March 2016 Welcome to all our members and guests to the REDLANDS MODERN COUNTRY MUSIC CLUB. We trust you will have a great night, sƟrring up some old great memories. MĆėĈč SĔĈĎĆđ - 5ęč MĆėĈč 2016 R½ÄÝ MÊÙÄ CÊçÄãÙù MçÝ® C½ç 1 MÙ« ϤϢϣϨ Executive Committee 2015- 2016 President – Kevin Brown 3829 2759 / 0417 532 807 [email protected] CommiƩee – Allen McMonagle Vice President – Peter Cathcart 3390 2066 / 0413 877 756 3423 2200 / 0459 991 708 [email protected] [email protected] CommiƩee – Bill Healey Secretary – Rowena Braaksma 3206 4305 / 0411 630 919 3800 0757 / 0407 037 579 [email protected] [email protected] CommiƩee – Des Boughen Treasurer – Dehlia Brown 3207 7527 / 0415 077 452 3829 2759 / 0409 430 211 [email protected] [email protected] OFFICE BEARERS 2015-2016 Assistant Treasurer Peter Cathcart Bar Manager Karen Wooon Building & Equipment Maintenance Des Boughen Champs Representave Dehlia Brown Country Music Fesval Coordinator Margie Campbell, Dawn Healey Entertainment Coordinator Allen McMonagle, Margie Campbell Fire Warden Kevin Brown First Aid Coordinator Jan Howard Lighng Coordinator Neil Wills Membership Registrar Peter Cathcart, Pam Faulkner Monthly Socials Door/Raffles Lorraine Bickford, Gwenda Quinn Monthly Socials Program Commiee Margie Campbell, Dennis Bubke Newsleer Editor Michael Burdee Food Commiee Coordinator Garth Brand Stage Managers Dennis Bubke Sound Producon Team Coordinator Des Boughen Web Coordinator Stephen Wooon Photographer Rosie Sheehan R½ÄÝ MÊÙÄ CÊçÄãÙù MçÝ® C½ç 2 MÙ« ϤϢϣϨ CONTENTS CLUB INFORMATION - Page 4 & 5 CLUB SPONSORS - Page CLUB REPORTS - Page 6 to 9 CLUB PHOTOS- Page 10 to 13 ANSWERS - Page 27 MEMBER ARTICLES - Page 22 to 27 ARTISTS & MEMBERS - Page 14 to 17 ENTERTAINMENT - Page 18 to 21 EDITORS NOTE Well what a ripper of a social we had in February! Thank you to all of you that had such kind words about the magazine— it is much appreciated. -

PLAYLIST 900 Songs, 2.3 Days, 7.90 GB

Page 1 of 17 MAIN PLAYLIST 900 songs, 2.3 days, 7.90 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Waterloo 2:43 101 Hits - Are We There Yet?! - CD4 Abba 2 Hello 3:57 ADELE 3 They Should Be Ringing (Single Edit) 3:28 Adore 4 The Memory Reel 3:24 LEAVES Advrb 5 You Look Good In Blue 2:18 triple j Unearthed Al Parkinson 6 Closer 3:55 Alana Wilkinson Alana Wilkinson 7 Good For You 3:37 Good For You Alana Wilkinson 8 fixture picture 4:07 Designer Aldous Harding 9 Good Conversation 3:16 The Turning Wheel Alex Hallahan 10 Don't Be So Hard On Yourself 4:18 Alex Lahey 11 Everybody's Laughing 3:50 Watching Angels Mend Alex Lloyd 12 Easy Exit Station 3:01 Watching Angels Mend Alex Lloyd 13 January 3:03 Ali Barter 14 I Feel Better But I Don't Feel Good 3:32 Alice Skye 15 Push 3:14 Alta 16 Remember That Sunday 2:37 Alton Ellis 17 Keep My Cool (with intro) 3:01 Aluka 18 Moana Lisa 3:44 I Woke Up This Morning After a Dream Amaringo 19 Sacred 4:44 Amaringo 20 I Got You 2:58 Love Monster Amy Shark 21 All Loved Up 3:30 Love Monster Amy Shark 22 Sisyphus 4:07 Andrew Bird 23 The Beloved - with intro 5:57 Carved Upon the Air Anecdote 24 The Sea - with intro 4:25 Carved Upon the Air Anecdote 25 No Secrets 4:18 101 Aussie Hits [CD2] The Angels 26 Pasta 4:38 Salt Angie McMahon 27 Missing Me 3:17 Salt Angie McMahon 28 Ring My Bell 3:17 Gold_Sensational 70's_ [Disc 1] Anita Ward 29 Nobody Knows Us - with intro 4:44 Nobody Knows Us Anna Cordell 30 You - with intro 5:41 Nobody Knows Us Anna Cordell 31 Train In Vain 4:44 Medusa Annie Lennox 32 Pale Bue Dot 3:04 Stay Fresh Annual -

Music Business and the Experience Economy the Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy

Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy . Peter Tschmuck • Philip L. Pearce • Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Editors Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Institute for Cultural Management and School of Business Cultural Studies James Cook University Townsville University of Music and Townsville, Queensland Performing Arts Vienna Australia Vienna, Austria Steven Campbell School of Creative Arts James Cook University Townsville Townsville, Queensland Australia ISBN 978-3-642-27897-6 ISBN 978-3-642-27898-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27898-3 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013936544 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

Have You Ever Seen the Sun Rise by Don Srisuriyo a Thesis Presented To

Have You Ever Seen the Sun Rise by Don Srisuriyo A thesis presented to the Honors College of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the University Honors College Spring 2019 Have Your Ever Seen the Run Rise by Don Srisuriyo APPROVED: ____________________________ Mr. Matt Burleson Department of English ______________________________ Dr. Steven E. Severn Department of English ___________________________ Dr. Fred Arroyo Department of English ___________________________ Dr. Philip E. Phillips, Associate Dean University Honors College ii To the stranger I didn’t know, the friend I won’t forget. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Matt Burleson, my primary advisor on this project, for the support that he has given me every step of the way. Without our conversations, I would have never seen things from a different perspective. Without your lectures on literature, I would have never figured out the true meaning of Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” and that has made all the difference. I would like to thank Dr. Fred Arroyo, my second reader on this project, for his advice on creative writing. Without his years of experience and his knowledge of creative writing, this story would have failed to reach its full potential. Finally, I would like to thank Jessi Shipley, my former eighth-grade English teacher, who was the first person to read any of my creative writing pieces. Without her simple words of praise, I would have never found the strength to write this story. iv Abstract As advanced social animals, humans have adapted with the times to satisfy their social needs. -

King Powder About a Dozen Years Ago

M.mT&T Our prases are turn Pretty Cards lor out s6me pretty' T hat Purpose work these days. Printed or Blank. OUR PRICE 25 cards for 25 cents By mail or at tbe of fice. DELTA, OHIO, FRIDAY MORNING, JULY 7 1899 i Mr. and Mrs. W .J. Clizbejof Chica go, having learned through tbe Atlas that Delta would not celebrate tbis | year, came up to enjoy a quiet 4tb with ber parents, Dr. and Mrs., Odell I and otber friends. If you lost a pocketbook with a IS TO BE LOC TED IN DELTA. Frank Bealer of Fremont, spent tbe small amount of money in it, call on 4th here. He lived here when a boy Jno. Blondell of north Wood street. king Powder about a dozen years ago. He finds , I will make my next trip to Wause __ now'bis boy friends of the bid time, on for paying taxes on Wednesday Ju Mad? from pure gsown up men and many of them ly 12, bring along your last receipt. gone. He particularly missed Wes W. E. F o w l x b . cream of tartar. Baker. While for the next few weeks the Capt. J. O. Rose of the 86th O. V.T. churches in town will unite in union has been spending a few days,the guest Sunday evening services, tbe Young of bis neice, Mrs. S. T. Shaffer. He Peoples’ societies will meet at their was a member of .the 14tb O. V. I., own places of meeting. 38th O. V. I. and the 86th O. -

Nonhuman Voices in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Material Culture

i NONHUMAN VOICES IN ANGLO- SAXON LITERATURE AND MATERIAL CULTURE ii Series editors: Anke Bernau and David Matthews Series founded by: J. J. Anderson and Gail Ashton Advisory board: Ruth Evans, Nicola McDonald, Andrew James Johnston, Sarah Salih, Larry Scanlon and Stephanie Trigg The Manchester Medieval Literature and Culture series publishes new research, informed by current critical methodologies, on the literary cultures of medieval Britain (including Anglo- Norman, Anglo- Latin and Celtic writings), including post- medieval engagements with and representations of the Middle Ages (medievalism). ‘Literature’ is viewed in a broad and inclusive sense, embracing imaginative, historical, political, scientific, dramatic and religious writings. The series offers monographs and essay collections, as well as editions and translations of texts. Titles Available in the Series The Parlement of Foulys (by Geoffrey Chaucer) D. S. Brewer (ed.) Language and imagination in the Gawain- poems J. J. Anderson Water and fire:The myth of the Flood in Anglo- Saxon England Daniel Anlezark Greenery: Ecocritical readings of late medieval English literature Gillian Rudd Sanctity and pornography in medieval culture:On the verge Bill Burgwinkle and Cary Howie In strange countries: Middle English literature and its afterlife: Essays in Memory of J. J. Anderson David Matthews (ed.) A knight’s legacy: Mandeville and Mandevillian lore in early modern England Ladan Niayesh (ed.) Rethinking the South English legendaries Heather Blurton and Jocelyn Wogan- Browne (eds) -

Graham “Buzz” Bidstrup Speaker Biography 2016 Graham “Buzz” Bidstrup Was Born in Adelaide on the 30Th August 1952

Graham “Buzz” Bidstrup Speaker Biography 2016 Graham “Buzz” Bidstrup was born in Adelaide on the 30th August 1952. Boasting a rich musical history, Adelaide’s music scene flourished in part to the influx of European and United Kingdom migrants in the 40s and 50s and 60s who brought with them the sounds that would ultimately birth the Australian Music Industry in the 70s 80s and 90s. Buzz played drums in his school band when he was ten and learned some piano and taught himself some basic guitar at the age of twelve. By the age of fourteen he was playing drums semi-professionally in and around Adelaide. From the teenage years until his early twenties, Buzz continued drumming while completing his tertiary studies in Mechanical Engineering at the Adelaide University of Technology. By the time he left Adelaide in the early seventies to live in England, he was a well-respected session musician and writer. Travelling through Europe and North Africa occasionally playing drums and guitar on a free-lance basis while soaking up the atmosphere. Upon his return home to Australia in 1976, Buzz was offered a job as drummer with a young emerging band known then as Angel City and he made the decision to move from Adelaide to Sydney. The Angels as they became known, were one of Australia’s most successful artists and from 1976 to 1981 Buzz toured, played drums and recorded four albums, three of which reached Platinum status) He co-wrote one of the Angel’s biggest hits, No Secrets, which made it to Top 5 Australia, Top 10 Portland, Seattle USA and Canada, touring several times through the USA and Europe with the band. -

Ellsworth American, a in Management, As to of Allowing Smoking on the Premises

ADDtUlfttmwtft LOCAL AFFAIRS Ellsworth Falls, and J. H. Crocker, of c urriitrmtnt®. Bangor. Nr.Vf AUVKKTHRMKNTN THIS WKKK.j The winter term of the high school and all the city schools will begin Monday, J A Cunningham—Notice. * Burrill H 0 Austin—Furniture. Jan. 5. Miss Lida A. True has been The National Bank C L Morsng -Dry good*. elected teacher of the School street pri- J A Haynes- Groceries. William E Whiting—Insurance. mary school. O A Pare OF her—Apothecary. Irene O. K will hold its an- ELLSWORTH A (loir.—Bakery. chapter, H., <.'ir«n«’i hotel. nual sale of aprons and home-made candy The Kohinson Co—Jewelry. Notice at Manning hall next Friday afternoon, "-Service annual—Notice. will 2 Probate you cent, on notice—William Foster Aptborp. from 2 to 5. Circle supper at 6.30, followed Safety pay The two factors worth per your Exec notice—George K. Farmer. j only considering in selecting a bank regular meeting. Admr notice—Henry K. Davis. by for the transaction of your business. Probate check balances of or notice—Jetinie Eliza Ilersey et als. Dr. E former $500 over, Notice of George Fellows, president foreclosure—Luman C shepherd. The Itsnkrupt's notice- George J Stafford. of the University of Maine and h summer ; UNION TRUST COMPANY of Ellsworth with a Non-resident interest tax notice -Orland. resident of Bayaide, has Just been in- i crediting; monthly —Hurry. Capital of $100,000 —Tremont. augurated hs president of Milliken uni- and service and Surplus Profits, $100,000 Unsurpassed monthly interest should be an versity, D.catur, 111. -

Native American Flute Meditation: Musical Instrument Design

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2008 Native American Flute Meditation: Musical Instrument Design, Construction and Playing as Contemplative Practice Daniel Cummings University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Mental and Social Health Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Daniel, "Native American Flute Meditation: Musical Instrument Design, Construction and Playing as Contemplative Practice" (2008). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 104. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/104http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/104 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Native American Flute Meditation: musical instrument design, construction and playing as contemplative practice by Dan Cummings © 2008 1 Introduction The two images on the preceding cover page represent the two traditions which have most significantly informed and inspired my personal flute journey, each in its own way contributing to an ongoing exploration of the design, construction and playing of Native American style flutes, as complementary aspects of a musically-oriented meditation practice. The first image is a typical artist’s rendition of Kokopelli, the flute-playing fertility deity who originated in the art and folklore of several Native North American cultures, particularly in the Southwestern region of the United States. Said to be representative of the spirit of music, today Kokopelli has become a ubiquitous symbol and quickly recognizable commercial icon associated with the Native American flute, or Native music and culture in general. -

PLAYLIST 16.0 - AUG 2020 - FEB 2021 900 Songs, 2.3 Days, 5.50 GB

Page 1 of 17 INDIGO FM - PLAYLIST 16.0 - AUG 2020 - FEB 2021 900 songs, 2.3 days, 5.50 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 The Bond - with intro 4:35 Adrian Clark 2 Kelly Watch The Stars 3:46 Electrospective Air 3 I Believe To My Soul 4:28 Rare & Well Done D1 (Rare) Al Kooper 4 Rib Cage 3:36 Alana Wilkinson Alana Wilkinson 5 Good For You 3:37 Good For You Alana Wilkinson 6 Hard Rock Gold 4:33 Hidden Hand Alaska String Band 7 Workin' Man Blues 3:57 Working Man Albert Cummings 8 The Barrel 4:53 Uncut 2020.01 The Sound of 2019 - 15 Tracks of the Year's… Aldous Harding 9 Before Too Long 3:04 Alex Cameron 104:05 4:07 Alex Lleo 11 Everybody's Laughing 3:50 Watching Angels Mend Alex Lloyd 12 I Think You're Great 3:47 I Think You're Great Alex the Astronaut 13 Split The Sky 4:07 Split the Sky Alex the Astronaut 14 Steppenwolf Express 3:47 On The Move To Chakino Alexander Tafintsev 15 The Captain (Live From Inside) 3:40 Live From Inside Ali Barter 16 I Won't Lie (Live From Inside) 3:49 Live From Inside Ali Barter 17 Ticket To Heaven feat. Thelma Plum 4:17 Alice Ivy 18 Don't Sleep 3:24 Alice Ivy 19 King Of The World 3:45 triple j Unearthed Alice Night 20 Rainbow Song 3:59 triple j Unearthed Alice Night 21 Friends With Feelings 4:15 Alice Skye 22 Grand Ideas 3:12 Alice Skye 23 Sacred 4:44 Amaringo 24 Endangered Man 4:35 Rituals Amaya Laucirica 25 I Said Hi 2:50 Love Monster Amy Shark 26 Never Coming Back 3:14 Love Monster Amy Shark 27 Me & Mr. -

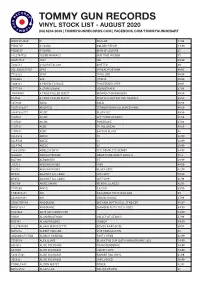

Vinyl Stock List - August 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | Tommygunrecords.Com | Facebook.Com/Tommygunhobart

TOMMY GUN RECORDS VINYL STOCK LIST - AUGUST 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | TOMMYGUNRECORDS.COM | FACEBOOK.COM/TOMMYGUNHOBART WARPLP302X !!! WALLOP 47.99 PIE027LP #1 DADS GOLDEN REPAIR 44.99 PIE005LP #1 DADS MAN OF LEISURE 35 8122794723 10,000 MANIACS OUR TIME IN EDEN 45 SSM144LP 1927 ISH 39.99 7202581 24 CARAT BLACK GHETTO 69 USI_B001655701 2PAC 2PACALYPSE NOW 49.95 7783828 2PAC THUG LIFE 49.99 FWR004 360 UTOPIA 49.99 5809181 A PERFECT CIRCLE THIRTEENTH STEP 49.95 6777554 A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK 67.99 JIV41490.1 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST MIDNIGHT MARAUDERS 49.99 R14734 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAVELS 69.99 5351106 ABBA GOLD 49.99 19075850371 ABORTED TERRORVISION COLOURED VINYL 49.99 88697383771 AC/DC BLACK ICE 49.99 5107611 AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK 41.99 5107621 AC/DC POWERAGE 47.99 5107581 ACDC 74 JAIL BREAK 49.99 5107651 ACDC BACK IN BLACK 45 XLLP313 ADELE 19 32.99 XLLP520 ADELE 21 32.99 XLLP740 ADELE 25 29.99 1866310761 ADOLESCENTS THE COMPLETE DEMOS 34.95 LL030LP ADRIAN YOUNGE SOMETHING ABOUT APRIL II 52.8 M27196 AEROSMITH ST 39.99 J12713 AFGHAN WHIGS 1965 49.99 P18761 AFGHAN WHIGS BLACK LOVE 42.99 OP048 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2012-2017 59.99 OP053 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2017-2019 61.99 S80109 AIMEE MANN MENTAL ILLNESS 42.95 7747280 AINTS 5,6,7,8,9 39.99 1.90296E+11 AIR CASANOVA 70 PIC DISC RSD 40 2438488481 AIR VIRGIN SUICIDE 37.99 SPINE799189 AIRBOURNE BREAKIN OUTTA HELL STND EDT 45.95 NW31135-1 AIRBOURNE DIAMOND CUTS THE B SIDES 44.99 FN279LP AK79 40TH ANNIV EDT 63.99 VS001 ALAN BRAUFMAN VALLEY OF SEARCH 47.99 M76741 ALAN PARSONS I