Notes on Lens Aperture, Shutter Speed and ISO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Photographs

Taking Photographs The relationship between aperture and shutter speed in taking correctly exposed photos Understanding relationship between SHUTTER SPEED & APERTURE SHUTTER SPEED & APERTURE Range of Apertures listed on the left and shutter speeds on the right CORRECT EXPOSURE MACRO / HIGH DEPTH OF FIELD SHOTS This is where the balance comes in – for each unique photo opportunity there is an exact amount of light required for proper exposure. In this example, a higher F stop number lets in very little light, so the shutter must remain open longer to allow in the correct amount of light for a good exposure. (BUT THESE ARE NOT THE ONLT SETTINGS THAT WILL GIVE A CORRECT EXPOSURE) CORRECT EXPOSURE SPORTS / SHALLOW DEPTH OF FIELD SHOTS Shooting exactly the same scene as before, we can set the shutters speed to its highest setting. This allows very little time for the light to enter the camera. In order to get a proper exposure, the aperture must be much larger than before to allow in the additional light needed. For a given exposure, shutter speed and aperture have to be in balance and work together like a teeter-totter (balance bar and fulcrum) Using APERTURE PRIORITY mode Most cameras allow you to select some degree of automation – one of these modes is APERTURE PRIORITY. With this mode YOU set the aperture and the camera will automatically select a shutter speed to give the correct exposure. The camera still uses this balance principal to do this. Using SHUTTER PRIORITY mode With SHUTTER PRIORITY mode YOU set the shutter speed and the camera will automatically select an aperture to give the correct exposure. -

35 Mm Aperture Priority 35Mm Cameras This Manual Is for Reference and Historical Purposes, All Rights Reserved

35 mm Aperture Priority 35mm cameras This manual is for reference and historical purposes, all rights reserved. This page is copyright © by [email protected], M. Butkus, NJ. This page may not be sold or distributed without the expressed permission of the producer I have no connection with any camera compnay On-line camera manual library This is the full text and images from the manual. This may take 3 full minutes for all images to appear. If they do not all appear. Try clicking the browser "refresh" or "reload button" or right click on the image, choose "view image" then go back. It should now appear. To print, try printing only 3 or 4 pages at a time. Back to main on-line manual page If you find this manual useful, how about a donation of $3 to: M. Butkus, 29 Lake Ave., High Bridge, NJ 08829-1701 and send your e-mail address so I can thank you. Most other places would charge you $7.50 for a electronic copy or $18.00 for a hard to read Xerox copy. This will allow me to continue to buy new manuals and pay their shipping costs. It'll make you feel better, won't it? If you use Pay Pal or wish to use your credit card, click on the secure site below. 35mm SLR EE Selection Guide Aperture-Priority INTRODUCTION 2 PENTAX ES THE APERTURE-PRIORITY SYSTEM YASHICA ELECTRO AX PROS AND CONS MORE ON THE WAY The Future What Does It All Mean? MINOLTA XK Should You Buy One? NIKKORMAT EL INTRODUCTION Progress towards exposure automation has been slow, but since the original Konica Autoreflex appeared in 1968, the pace has accelerated and there are now 10 35mm SLR cameras so equipped. -

Aperture Priority Mode

PHOTOGRAPHER’S GUIDE TO THE LEICA D-LUX 5 particular aperture or shutter speed at the outset. If you need that degree of control, you’ll need to select Aperture Priority, Shutter Priority, or Manual for your shooting mode. There is one specific issue related to the lack of control over aperture and shutter speed when you’re using Program mode. When that shooting mode is set, the Minimum Shutter Speed setting will be activated; you cannot turn it off. The slowest minimum shutter speed you can set in that situation is one second. So if you are trying to take a time exposure in a dark area (using a tripod, presumably), where the correct shutter speed would be, say, five seconds, the camera will not expose the picture properly. The minimum shutter speed setting of one second will be the longest exposure possible. If you expect to have exposures longer than one second, you need to select a shooting mode other than Program. (Namely, Manual, Aper- ture Priority, Shutter Priority, or certain Scene types.) Aperture Priority Mode You set this shooting mode by turning the Mode dial to the capital “A” that stands alone, not the “A” inside the camera icon. This mode is similar toProgram mode in the functions that are available for you to control, but, as the name implies, it also gives you, the photographer, more control over the cam- era’s aperture. Before discussing the nuts and bolts of the settings for this mode, let’s talk about what aperture is and why you would want to control it. -

Rolleiflex-6000.Pdf

Rolleiflex 6000-System Lenses and Dedicated Accessories www.mr-alvandi.com Top-notch Lenses Only the best lenses are good enough for a profes- Glass sional camera system. A combination of proper lens curvatures and suitable For your Rolleiflex 6008 AF and Rolleiflex 6008 Integral glass types are your guarantee that the Rollei line of you may choose between lenses from ultra-wide-angle, lenses are optimally corrected for aberrations for sharp wide-angle and standard lenses to telephoto, zoom and brilliant pictures. Carl Zeiss, Schneider-Kreuznach and several special-purposes lenses. All of them cut- and Franke & Heidecke use advanced glass types, some ting-edge products made by Carl Zeiss and Schneider- of which with particularly high refractive indices. Kreuznach, the world-famous specialists for medium- format optics. All of them with Rollei HFT coating (High Mechanics Fidelity Transfer) for optimum flare suppression and bril- A lens consists of several elements, some of which may liant colors. be combined in components. These are axially shifted for focusing and zooming, sometimes even in opposite Our PQ (Professional Quality) and PQS lenses, the latter directions. All these motions have to be very precise in with a top shutter speed of 1/1000 s, are the result of order not to degrade the high performance of the advanced optical design techniques, innovative technol- lenses over their entire focusing and zooming ranges. ogy and permanent optimization. All of them use the Precise manufacturing techniques and high-quality unique Rollei Direct-Drive technology: The diaphragm materials make sure that the tight tolerances are met and shutter blades in the lens are driven by two linear even after many years of use. -

Aperture Priority Mode F/4.0 at 1/25, Among Others

Chapter 3: Shooting Modes for Still Images | 23 The Program Shift function is available only in Program you’re taking pictures quickly using Program mode, and mode; it works as follows. Once you have aimed the you want a fast way to tweak the settings somewhat. camera at your subject, the camera displays its chosen settings for shutter speed and aperture in the lower- Another important aspect of Program mode is that it left corner of the screen. At that point, you can turn the expands the choices available through the Shooting Control dial at the upper right of the camera’s back, and menu, which controls many of the camera’s settings. the values for shutter speed and aperture will change, You will be able to make choices involving ISO if possible under current conditions, to different sensitivity, metering mode, DRO/HDR, white balance, values for both settings while keeping the same overall Creative Style, Picture Effect, and others that are not exposure of the scene. available in the Auto modes. I won’t discuss those settings here; if you want to explore that topic, see With this option, the camera “shifts” the original the discussion of the Shooting menu in Chapter 4 for exposure to your choice of any of the matched pairs information about all of the different selections that that appear as you turn the Control dial. For example, if are available. the original exposure was f/2.8 at 1/50 second, you may see equivalent pairs of f/3.2 at 1/40, f/3.5 at 1/30, and Aperture Priority Mode f/4.0 at 1/25, among others. -

Rollei Rolleiflex 6008 Manual

Rollei rolleiflex 6008 manual Continue In 1976, Rollei released SLX, a fully electronic mid-range SLR format, to compete with the famous Hasselblad machines. With a built-in light meter, automatic motor upfront and automatic shutter exposure, it was in many ways a much more advanced camera than the camera produced by Swedish rival Rollei. The photographic world paid attention to it. Rolley made another incredible camera. In 1984, a brand-new series of Rollei MF SLR was presented; 6000 series. Advances in electronics throughout the 1980s and 90s meant Rolley's newest MIRRORS could be smarter, stronger, and more features than any average SLR format that came before them. Over the next thirty years the brand will continue to push the range forward, bringing some of the best mid-format SLRs to the world. But even though the 6000 series cameras were worthy of special attention, they never seemed to achieve the popularity of those Hasselblad. It's a disgrace, so let's fix it. With incredible build quality and unrivalled optics from some of the world's best lens manufacturers, the 6000 series should be on any true list of computer geek avid cameras. And of the many 6000 series of cameras, one to own can be those marked 6008.The 6008 Professional, 6008 Professional SRC 1000, and 6008 Integral all pack the greatest combination of features, high modularity, and the best build quality of any camera in the 6000 series. While other cameras in the lineup give up certain features (6003 loses its interchangeable backs and 6001 lacks a light meter, for example) 6008 models do everything (and often much more) than any shooter can ask for a camera. -

Download the Olympus TG-5 Settings Guides

OLYMPUS TG-5 BEST SETTINGS MACRO PHOTO WITH STROBE • Set them and forget them On The Boat • May evolve with your skills Live View Boost: ON Exposure Compensation: -2 Stops File Type: RAW / RAW & JPEG ISO: 100 (Lowest) White Balance: Auto White Balance Focus: Autofocus Flash: Fill-In (Default) Strobe: TTL / S-TTL • Based on scene & subject In The Water • May change during the dive Mode: Microscope (or P) Working Distance: 1 - 6 inches Zoom: As Needed Focus: Critical Detail Area (Eyeball) Strobe: Equal distance between lens & subject Strobe Position: Above for good shadows ©BACKSCATTER BACKSCATTER • +1-831-645-1082 • [email protected] • www.backscatter.com OLYMPUS TG-5 BEST SETTINGS PHOTO WITH A VIDEO LIGHT • Set them and forget them On The Boat • May evolve with your skills Live View Boost: ON Exposure Compensation: -0.3 Stops File Type: RAW / RAW & JPEG ISO: 100 -400 (Lowest Possible) White Balance: Auto White Balance Focus: Autofocus Flash: Off Stabilization: On Frame Rate: Single - High • Based on scene & subject In The Water • May change during the dive Mode: Microscope (or P) Shutter Speed: 1/250 or Faster Working Distance: 1 - 6 inches Zoom: As Needed Focus: Critical Detail Area (Eyeball) Light Power: Brightest Possible Light Position: Forward & Down ©BACKSCATTER BACKSCATTER • +1-831-645-1082 • [email protected] • www.backscatter.com OLYMPUS TG-5 BEST SETTINGS WIDE-ANGLE PHOTO WITH A STROBE • Set them and forget them On The Boat • May evolve with your skills Accessory: Backscatter M52 Wide lens File Type: RAW / RAW & JPEG -

Camera Manual Mode Exposure Compensation

camera manual mode exposure compensation File Name: camera manual mode exposure compensation.pdf Size: 2032 KB Type: PDF, ePub, eBook Category: Book Uploaded: 15 May 2019, 18:40 PM Rating: 4.6/5 from 590 votes. Status: AVAILABLE Last checked: 15 Minutes ago! In order to read or download camera manual mode exposure compensation ebook, you need to create a FREE account. Download Now! eBook includes PDF, ePub and Kindle version ✔ Register a free 1 month Trial Account. ✔ Download as many books as you like (Personal use) ✔ Cancel the membership at any time if not satisfied. ✔ Join Over 80000 Happy Readers Book Descriptions: We have made it easy for you to find a PDF Ebooks without any digging. And by having access to our ebooks online or by storing it on your computer, you have convenient answers with camera manual mode exposure compensation . To get started finding camera manual mode exposure compensation , you are right to find our website which has a comprehensive collection of manuals listed. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. Home | Contact | DMCA Book Descriptions: camera manual mode exposure compensation It only takes a minute to sign up. In full manual mode you can not change exposure compensation Are other advanced cameras like this In Canon cameras it doesnt do even that.But it is named Manual Exposure Mode. Start with reading about the ExposureTriangle. If you understand that, you would not be asking this When you are in manual mode and set all these, that is it. -

Getting Off the Auto Setting on Your Camera

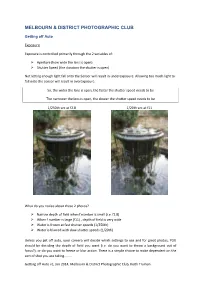

MELBOURN & DISTRICT PHOTOGRAPHIC CLUB Getting off Auto Exposure Exposure is controlled primarily through the 2 variables of: Aperture (how wide the lens is open) Shutter Speed (the duration the shutter is open) Not letting enough light fall onto the Sensor will result in underexposure. Allowing too much light to fall onto the sensor will result in overexposure. So, the wider the lens is open, the faster the shutter speed needs to be The narrower the lens is open, the slower the shutter speed needs to be 1/250th sec at f2.8 1/20th sec at f11 What do you notice about these 2 photos? Narrow depth of field when f number is small (i.e. f2.8) When f number is large (f11) , depth of field is very wide Water is frozen at fast shutter speeds (1/250th) Water is blurred with slow shutter speeds (1/20th) Unless you get off auto, your camera will decide which settings to use and for great photos, YOU should be deciding the depth of field you want (i.e. do you want to throw a background out of focus?), or do you want to freeze or blur action. There is a simple choice to make dependent on the sort of shot you are taking........ Getting off Auto v1, Jan 2014, Melbourn & District Photographic Club, Keith Truman Is controlling depth of field more important than shutter speed (if it is you should use Aperture Priority)? Is freezing or blurring action more important than controlling depth of field (if it is you should use Shutter Priority. -

Backup of 2014 Update Backup of Lensbaby Class Lesson 1 Copy

Lensbaby Magic Lesson 1 “When subject matter is forced to fit into preconceived patterns, there can be no freshness of vision.” -Edward Weston Welcome to my Lensbaby Magic Class! The Basics Craig Strong invented the Lensbaby when he was trying to find a different look for his images. He was looking for a way to be able to do this in-camera, instead of spending hours sitting at his computer. He wanted to combine the soft, imperfect look produced by Holga film cameras, with the convenience of digital imagery. He says that the Lensbaby he developed gave him some options to match a certain mood in a theme, or to render an image the way he envisioned it. With the trend these day being the most refined, precise, high speed automatic lenses, the Lensbaby is a refreshing Lensbaby Magic Kathleen Clemons 1 step backwards. It’s sort of an odd combination of an old, manual focus lens where you had to do it right the first time, and a modern day video game joystick. The original lens models are mounted on a plastic bellows, which allows you to manually focus by pushing, pulling and bending. A selected part of your image will be in focus, and you control just where that ‘sweet spot” of focus will be by manipulating either the bellows section (the part that looks like vacuum cleaner hose) on the Muse and the original models, or the focus ring on the Composer, which has a ball and socket type design. The remaining areas of your image are softly and gradually blurred, creating unique, eye-catching images. -

Aperture Priority – a Beginners Guide

Aperture Priority – A Beginners Guide Here's my take on the various exposure methods that I use and the circumstances in which I use them. I'll tell you the story of how this image was taken, using "A" or "Aperture Priority" mode: The "aperture" is the "f" stop or "f" number. It is the opening in the iris diaphragm in the lens and controls the intensity of light (or the brightness of the image) passing through the lens to the sensor. The term "stop" comes from the days of plate cameras when the aperture was a metal disc with a hole drilled in its centre that was dropped into a slot in the lens and thus "stopped" the light according to the size of the hole. The "f" number is the ratio of the diameter of the aperture to the focal length of the lens. Each progressive f number allows double (or half) the amount of light to pass through the lens. Here is the table of progressive f numbers: f/1.0 - f/1.4 - f2.0 - f2.8 - f/4 - f/5.6 - f/8 - f/11 - f/16 - f/22 - f/32 - f/64 These are the basic f-stops that every photographer should know. They are known as the “full” stops. The shutter speed is the duration of time that this light is allowed to strike the sensor, controlled in fractions of a second, each progressive setting giving half (or double) the duration of the previous setting. Here is the shutter speed progression table in one EV steps: 1/15 - 1/30 - 1/60 - 1.125 - 1/250 - 1/500 - 1/1000 - 1/2000 - 1/4000 These are the basic shutter speeds that every photographer should know. -

Photography Topics of Discussion

New Camera, New Features, New Memories Presented by: Brian Castle, Picture Perfect Photography Topics of Discussion Quality Settings Megapixels, Fine, File Type’s (jpeg’s) White Balance Macro Image Stabilization Exposure Compensation Metering Aperture Shutter Speed/ISO What are Megapixels? The number of megapixels a camera features can also help to determine the size photos you can print or the amount of cropping you can do. Generally 3-6 megapixels will be enough for general snapshots and can be blown up to virtually any size under a 20x24 and still be sharp. Higher megapixels do not always produce a better print. Only if you plan to blow it up to huge sizes. If you definitely want to something you want to frame go for the higher megs. The higher the megapixels the more room it takes up on your memory card When you transfer the photos to your computer it takes up more room with higher megapixel use. Megapixel to amount of Photo conversion table Card size Number of photos 128MB 29 256MB 58 512MB 116 8 megapixel camera (3264 x 2448) File size: 4.2MB 1GB 232 2GB 464 4GB 929 Card size Number of photos 128MB 102 256MB 203 512MB 406 3 megapixel camera (2,048 x 1,536) 1GB 813 File size: 1.2MB 2GB 1625 4GB 3251 What Quality Settings do I use? RAW - Unprocessed TIFF - Unprocessed JPEG - Processed *Unprocessed – You have to process the photo in an editing type software. *Processed – The camera converts and establishes color, exposure, etc. based on how much contrast, saturation the camera thinks it needs to make a good photo Fine Tuning Normal – Fine – Superfine Basic – Normal – Fine Good – Better – Best Canon uses these symbols - Smooth is best, stepped in worst quality.