Rates of Reaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 12 Lecture Notes

Chemical Kinetics “The study of speeds of reactions and the nanoscale pathways or rearrangements by which atoms and molecules are transformed to products” Chapter 13: Chemical Kinetics: Rates of Reactions © 2008 Brooks/Cole 1 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 2 Reaction Rate Reaction Rate Combustion of Fe(s) powder: © 2008 Brooks/Cole 3 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 4 Reaction Rate Reaction Rate + Change in [reactant] or [product] per unit time. Average rate of the Cv reaction can be calculated: Time, t [Cv+] Average rate + Cresol violet (Cv ; a dye) decomposes in NaOH(aq): (s) (mol / L) (mol L-1 s-1) 0.0 5.000 x 10-5 13.2 x 10-7 10.0 3.680 x 10-5 9.70 x 10-7 20.0 2.710 x 10-5 7.20 x 10-7 30.0 1.990 x 10-5 5.30 x 10-7 40.0 1.460 x 10-5 3.82 x 10-7 + - 50.0 1.078 x 10-5 Cv (aq) + OH (aq) → CvOH(aq) 2.85 x 10-7 60.0 0.793 x 10-5 -7 + + -5 1.82 x 10 change in concentration of Cv Δ [Cv ] 80.0 0.429 x 10 rate = = 0.99 x 10-7 elapsed time Δt 100.0 0.232 x 10-5 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 5 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 6 1 Reaction Rates and Stoichiometry Reaction Rates and Stoichiometry Cv+(aq) + OH-(aq) → CvOH(aq) For any general reaction: a A + b B c C + d D Stoichiometry: The overall rate of reaction is: Loss of 1 Cv+ → Gain of 1 CvOH Rate of Cv+ loss = Rate of CvOH gain 1 Δ[A] 1 Δ[B] 1 Δ[C] 1 Δ[D] Rate = − = − = + = + Another example: a Δt b Δt c Δt d Δt 2 N2O5(g) 4 NO2(g) + O2(g) Reactants decrease with time. -

Andrea Deoudes, Kinetics: a Clock Reaction

A Kinetics Experiment The Rate of a Chemical Reaction: A Clock Reaction Andrea Deoudes February 2, 2010 Introduction: The rates of chemical reactions and the ability to control those rates are crucial aspects of life. Chemical kinetics is the study of the rates at which chemical reactions occur, the factors that affect the speed of reactions, and the mechanisms by which reactions proceed. The reaction rate depends on the reactants, the concentrations of the reactants, the temperature at which the reaction takes place, and any catalysts or inhibitors that affect the reaction. If a chemical reaction has a fast rate, a large portion of the molecules react to form products in a given time period. If a chemical reaction has a slow rate, a small portion of molecules react to form products in a given time period. This experiment studied the kinetics of a reaction between an iodide ion (I-1) and a -2 -1 -2 -2 peroxydisulfate ion (S2O8 ) in the first reaction: 2I + S2O8 I2 + 2SO4 . This is a relatively slow reaction. The reaction rate is dependent on the concentrations of the reactants, following -1 m -2 n the rate law: Rate = k[I ] [S2O8 ] . In order to study the kinetics of this reaction, or any reaction, there must be an experimental way to measure the concentration of at least one of the reactants or products as a function of time. -2 -2 -1 This was done in this experiment using a second reaction, 2S2O3 + I2 S4O6 + 2I , which occurred simultaneously with the reaction under investigation. Adding starch to the mixture -2 allowed the S2O3 of the second reaction to act as a built in “clock;” the mixture turned blue -2 -2 when all of the S2O3 had been consumed. -

Ochem ACS Review 23 Aryl Halides

ACS Review Aryl Halides 1. Which one of the following has the weakest carbon-chlorine bond? A. I B. II C. III D. IV 2. Which compound in each of the following pairs is the most reactive to the conditions indicated? A. I and III B. I and IV C. II and III D. II and IV 3. Which of the following reacts at the fastest rate with potassium methoxide (KOCH 3) in methanol? A. fluorobenzene B. 4-nitrofluorobenzene C. 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene D. 2,4,6-trinitrofluorobenzene 4. Which of the following reacts at the fastest rate with potassium methoxide (KOCH 3) in methanol? A. fluorobenzene B. p-nitrofluorobenzene C. p-fluorotoluene D. p-bromofluorobenzene 5. Which of the following is the kinetic rate equation for the addition-elimination mechanism of nucleophilic aromatic substitution? A. rate = k[aryl halide] B. rate = k[nucleophile] C. rate = k[aryl halide][nucleophile] D. rate = k[aryl halide][nucleophile] 2 6. Which of the following is not a resonance form of the intermediate in the nucleophilic addition of hydroxide ion to para -fluoronitrobenzene? A. I B. II C. III D. IV 7. Which chlorine is most susceptible to nucleophilic substitution with NaOCH 3 in methanol? A. #1 B. #2 C. #1 and #2 are equally susceptible D. no substitution is possible 8. What is the product of the following reaction? A. N,N-dimethylaniline B. para -chloro-N,N-dimethylaniline C. phenyllithium (C 6H5Li) D. meta -chloro-N,N-dimethylaniline 9. Which one of the reagents readily reacts with bromobenzene without heating? A. -

Reaction Kinetics in Organic Reactions

Autumn 2004 Reaction Kinetics in Organic Reactions Why are kinetic analyses important? • Consider two classic examples in asymmetric catalysis: geraniol epoxidation 5-10% Ti(O-i-C3H7)4 O DET OH * * OH + TBHP CH2Cl2 3A mol sieve OH COOH5C2 L-(+)-DET = OH COOH5C2 * OH geraniol hydrogenation OH 0.1% Ru(II)-BINAP + H2 CH3OH P(C6H5)2 (S)-BINAP = P(C6 H5)2 • In both cases, high enantioselectivities may be achieved. However, there are fundamental differences between these two reactions which kinetics can inform us about. 1 Autumn 2004 Kinetics of Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions geraniol epoxidation: • enantioselectivity is controlled primarily by the preferred mode of initial binding of the prochiral substrate and, therefore, the relative stability of intermediate species. The transition state resembles the intermediate species. Finn and Sharpless in Asymmetric Synthesis, Morrison, J.D., ed., Academic Press: New York, 1986, v. 5, p. 247. geraniol hydrogenation: • enantioselectivity may be dictated by the relative reactivity rather than the stability of the intermediate species. The transition state may not resemble the intermediate species. for example, hydrogenation of enamides using Rh+(dipamp) studied by Landis and Halpern (JACS, 1987, 109,1746) 2 Autumn 2004 Kinetics of Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions “Asymmetric catalysis is four-dimensional chemistry. Simple stereochemical scrutiny of the substrate or reagent is not enough. The high efficiency that these reactions provide can only be achieved through a combination of both an ideal three-dimensional structure (x,y,z) and suitable kinetics (t).” R. Noyori, Asymmetric Catalysis in Organic Synthesis,Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1994, p.3. “Studying the photograph of a racehorse cannot tell you how fast it can run.” J. -

Enzymatic Kinetic Isotope Effects from First-Principles Path Sampling

Article pubs.acs.org/JCTC Enzymatic Kinetic Isotope Effects from First-Principles Path Sampling Calculations Matthew J. Varga and Steven D. Schwartz* Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: In this study, we develop and test a method to determine the rate of particle transfer and kinetic isotope effects in enzymatic reactions, specifically yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (YADH), from first-principles. Transition path sampling (TPS) and normal mode centroid dynamics (CMD) are used to simulate these enzymatic reactions without knowledge of their reaction coordinates and with the inclusion of quantum effects, such as zero-point energy and tunneling, on the transferring particle. Though previous studies have used TPS to calculate reaction rate constants in various model and real systems, it has not been applied to a system as large as YADH. The calculated primary H/D kinetic isotope effect agrees with previously reported experimental results, within experimental error. The kinetic isotope effects calculated with this method correspond to the kinetic isotope effect of the transfer event itself. The results reported here show that the kinetic isotope effects calculated from first-principles, purely for barrier passage, can be used to predict experimental kinetic isotope effects in enzymatic systems. ■ INTRODUCTION staging method from the Chandler group.10 Another method that uses an energy gap formalism like QCP is a hybrid Particle transfer plays a crucial role in a breadth of enzymatic ff reactions, including hydride, hydrogen atom, electron, and quantum-classical approach of Hammes-Schi er and co-work- 1 ers, which models the transferring particle nucleus as a proton-coupled electron transfer reactions. -

5.3 Controlling Chemical Reactions Vocabulary: Activation Energy

5.3 Controlling Chemical Reactions Vocabulary: Activation energy – Concentration – Catalyst – Enzyme – Inhibitor - How do reactions get started? Chemical reactions won’t begin until the reactants have enough energy. The energy is used to break the chemical bonds of the reactants. Then the atoms form the new bonds of the products. Activation Energy is the minimum amount of energy needed to start a chemical reaction. All chemical reactions need a certain amount of activation energy to get started. Usually, once a few molecules react, the rest will quickly follow. The first few reactions provide the activation energy for more molecules to react. Hydrogen and oxygen can react to form water. However, if you just mix the two gases together, nothing happens. For the reaction to start, activation energy must be added. An electric spark or adding heat can provide that energy. A few of the hydrogen and oxygen molecules will react, producing energy for even more molecules to react. Graphing Changes in Energy Every chemical reaction needs activation energy to start. Whether or not a reaction still needs more energy from the environment to keep going depends on whether it is exothermic or endothermic. The peaks on the graphs show the activation energy. Notice that at the end of the exothermic reaction, the products have less energy than the reactants. This type of reaction results in a release of energy. The burning of fuels, such as wood, natural gas, or oil, is an example of an exothermic reaction. Endothermic reactions also need activation energy to get started. In addition, they need energy to continue. -

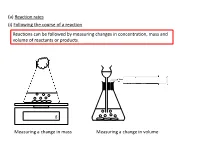

(A) Reaction Rates (I) Following the Course of a Reaction Reactions Can Be Followed by Measuring Changes in Concentration, Mass and Volume of Reactants Or Products

(a) Reaction rates (i) Following the course of a reaction Reactions can be followed by measuring changes in concentration, mass and volume of reactants or products. g Measuring a change in mass Measuring a change in volume Volume of gas produced of gas Volume Mass of beaker and contents of beaker Mass Time Time The rate is highest at the start of the reaction because the concentration of reactants is highest at this point. The steepness (gradient) of the plotted line indicates the rate of the reaction. We can also measure changes in product concentration using a pH meter for reactions involving acids or alkalis, or by taking small samples and analysing them by titration or spectrophotometry. Concentration reactant Time Calculating the average rate The average rate of a reaction, or stage in a reaction, can be calculated from initial and final quantities and the time interval. change in measured factor Average rate = change in time Units of rate The unit of rate is simply the unit in which the quantity of substance is measured divided by the unit of time used. Using the accepted notation, ‘divided by’ is represented by unit-1. For example, a change in volume measured in cm3 over a time measured in minutes would give a rate with the units cm3min-1. 0.05-0.00 Rate = 50-0 1 - 0.05 = 50 = 0.001moll-1s-1 Concentration moll Concentration 0.075-0.05 Rate = 100-50 0.025 = 50 = 0.0005moll-1s-1 The rate of a reaction, or stage in a reaction, is proportional to the reciprocal of the time taken. -

Determination of Kinetics in Gas-Liquid Reaction Systems

DOI: 10.2478/v10216-011-0014-y ECOL CHEM ENG S. 2012; 19(2):175-196 Hanna KIERZKOWSKA-PAWLAK 1* DETERMINATION OF KINETICS IN GAS-LIQUID REACTION SYSTEMS. AN OVERVIEW PRZEGL ĄD METOD WYZNACZANIA KINETYKI REAKCJI GAZ-CIECZ Abstract: The aim of this paper is to present a brief review of the determination methods of reaction kinetics in gas-liquid systems with a special emphasis on CO 2 absorption in aqueous alkanolamine solutions. Both homogenous and heterogeneous experimental techniques are described with the corresponding theoretical background needed for the interpretation of the results. The case of CO 2 reaction in aqueous solutions of methyldiethanolamine is discussed as an illustrative example. It was demonstrated that various measurement techniques and methods of analyzing the experimental data can result in different expressions for the kinetic rate constants. Keywords: gas-liquid reaction kinetics, stirred cell, stopped-flow technique, enhancement factor, CO 2 absorption, methyldiethanolamine Introduction Multiphase reaction systems are frequently encountered in chemical reaction engineering practice. Typical examples of industrially important processes where these systems are found include gas purification, oxidation, chlorination, hydrogenation and hydroformylation processes. Among them, the CO 2 removal by aqueous solutions of amines received considerable attention. Since CO 2 is regarded as a major greenhouse gas, potentially contributing to global warming, there has been substantial interest in developing amine-based technologies for capturing large quantities of CO 2 produced from fossil fuel power plants. Absorption of CO 2 by chemical solvents is the most popular and effective method which can be implemented in this sector. Industrially important alkanolamines for CO 2 removal are the primary amine monoethanolamine (MEA), the secondary amine diethanolamine (DEA) and diisopropanolamine (DIPA) and the tertiary amine methyldiethanolamine (MDEA) and triethanolamine (TEA) [1]. -

S.T.E.T.Women's College, Mannargudi Semester Iii Ii M

S.T.E.T.WOMEN’S COLLEGE, MANNARGUDI SEMESTER III II M.Sc., CHEMISTRY ORGANIC CHEMISTRY - II – P16CH31 UNIT I Aliphatic nucleophilic substitution – mechanisms – SN1, SN2, SNi – ion-pair in SN1 mechanisms – neighbouring group participation, non-classical carbocations – substitutions at allylic and vinylic carbons. Reactivity – effect of structure, nucleophile, leaving group and stereochemical factors – correlation of structure with reactivity – solvent effects – rearrangements involving carbocations – Wagner-Meerwein and dienone-phenol rearrangements. Aromatic nucleophilic substitutions – SN1, SNAr, Benzyne mechanism – reactivity orientation – Ullmann, Sandmeyer and Chichibabin reaction – rearrangements involving nucleophilic substitution – Stevens – Sommelet Hauser and von-Richter rearrangements. NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION Mechanism of Aliphatic Nucleophilic Substitution. Aliphatic nucleophilic substitution clearly involves the donation of a lone pair from the nucleophile to the tetrahedral, electrophilic carbon bonded to a halogen. For that reason, it attracts to nucleophile In organic chemistry and inorganic chemistry, nucleophilic substitution is a fundamental class of reactions in which a leaving group(nucleophile) is replaced by an electron rich compound(nucleophile). The whole molecular entity of which the electrophile and the leaving group are part is usually called the substrate. The nucleophile essentially attempts to replace the leaving group as the primary substituent in the reaction itself, as a part of another molecule. The most general form of the reaction may be given as the following: Nuc: + R-LG → R-Nuc + LG: The electron pair (:) from the nucleophile(Nuc) attacks the substrate (R-LG) forming a new 1 bond, while the leaving group (LG) departs with an electron pair. The principal product in this case is R-Nuc. The nucleophile may be electrically neutral or negatively charged, whereas the substrate is typically neutral or positively charged. -

Differential and Integrated Rate Laws

Differential and Integrated Rate Laws Rate laws describe the progress of the reaction; they are mathematical expressions which describe the relationship between reactant rates and reactant concentrations. In general, if the reaction is: 푎퐴 + 푏퐵 → 푐퐶 + 푑퐷 We can write the following expression: 푟푎푡푒 = 푘[퐴]푚[퐵]푛 Where: 푘 is a proportionality constant called rate constant (its value is fixed for a fixed set of conditions, specially temperature). 푚 and 푛 are known as orders of reaction. As it can be seen from the above expression, these orders of reaction indicate the degree or extent to which the reaction rate depends on the concentration of each reactant. We can say the following about these orders of reaction: 1. In general, they are not equal to the coefficients from the balanced equation. Remember: they are determined experimentally (unless a reaction is what we call an elementary reaction, but they are the exception). 2. Each reactant has its own (independent) order of reaction. 3. Orders of reaction are often times a positive number, but they can also be zero, a fraction and in some instances a negative number. 4. The overall reaction order is calculated by simply adding the individual orders (푚 + 푛). As it turns out, rate laws can actually be written using two different, but related, perspectives. Which are these two perspectives? What information does each provide? Read along and you will find out. On more thing – I must insist: it is not possible to predict the rate law from the overall balanced chemical reaction; rate laws must be determined experimentally. -

Reaction Rates: Chemical Kinetics

Chemical Kinetics Reaction Rates: Reaction Rate: The change in the concentration of a reactant or a product with time (M/s). Reactant → Products A → B change in number of moles of B Average rate = change in time ∆()moles of B ∆[B] = = ∆t ∆t ∆[A] Since reactants go away with time: Rate=− ∆t 1 Consider the decomposition of N2O5 to give NO2 and O2: 2N2O5(g)→ 4NO2(g) + O2(g) reactants products decrease with increase with time time 2 From the graph looking at t = 300 to 400 s 0.0009M −61− Rate O2 ==× 9 10 Ms Why do they differ? 100s 0.0037M Rate NO ==× 3.7 10−51 Ms− Recall: 2 100s 0.0019M −51− 2N O (g)→ 4NO (g) + O (g) Rate N O ==× 1.9 10 Ms 2 5 2 2 25 100s To compare the rates one must account for the stoichiometry. 1 Rate O =×× 9 10−−61 Ms =× 9 10 −− 61 Ms 2 1 1 −51−−− 61 Rate NO2 =×× 3.7 10 Ms =× 9.2 10 Ms Now they 4 1 agree! Rate N O =×× 1.9 10−51 Ms−−− = 9.5 × 10 61Ms 25 2 Reaction Rate and Stoichiometry In general for the reaction: aA + bB → cC + dD 11∆∆∆∆[AB] [ ] 11[CD] [ ] Rate ====− − ab∆∆∆ttcdtt∆ 3 Rate Law & Reaction Order The reaction rate law expression relates the rate of a reaction to the concentrations of the reactants. Each concentration is expressed with an order (exponent). The rate constant converts the concentration expression into the correct units of rate (Ms−1). (It also has deeper significance, which will be discussed later) For the general reaction: aA+ bB → cC+ dD x and y are the reactant orders determined from experiment. -

Alkyl Halides

Alkyl Halides Alkyl halides are a class of compounds where a halogen atom or atoms are bound to an sp3 orbital of an alkyl group. CHCl3 (Chloroform: organic solvent) CF2Cl2 (Freon-12: refrigerant CFC) CF3CHClBr (Halothane: anesthetic) Halogen atoms are more electronegative than carbon atoms, and so the C-Hal bond is polarized. The C-Hal (often written C-X) bond is polarized in such a way that there is partial positive charge on the carbon and partial negative charge on the halogen. Ch06 Alkyl Halides (landscape).docx Page 1 Dipole moment Electronegativities decrease in the order of: F > Cl > Br > I Carbon-halogen bond lengths increase in the order of: C-F < C-Cl < C-Br < C-I Bond Dipole Moments decrease in the order of: C-Cl > C-F > C-Br > C-I = 1.56D 1.51D 1.48D 1.29D Typically the chemistry of alkyl halides is dominated by this effect, and usually results in the C-X bond being broken (either in a substitution or elimination process). This reactivity makes alkyl halides useful chemical reagents. Ch06 Alkyl Halides (landscape).docx Page 2 Nomenclature According to IUPAC, alkyl halides are treated as alkanes with a halogen (Halo-) substituent. The halogen prefixes are Fluoro-, Chloro-, Bromo- and Iodo-. Examples: Often compounds of CH2X2 type are called methylene halides. (CH2Cl2 is methylene chloride). CHX3 type compounds are called haloforms. (CHI3 is iodoform). CX4 type compounds are called carbon tetrahalides. (CF4 is carbon tetrafluoride). Alkyl halides can be primary (1°), secondary (2°) or tertiary (3°). Other types: A geminal (gem) dihalide has two halogens on the same carbon.