Introducing Old Crane Woman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celtic Solar Goddesses: from Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven

CELTIC SOLAR GODDESSES: FROM GODDESS OF THE SUN TO QUEEN OF HEAVEN by Hayley J. Arrington A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Women’s Spirituality Institute of Transpersonal Psychology Palo Alto, California June 8, 2012 I certify that I have read and approved the content and presentation of this thesis: ________________________________________________ __________________ Judy Grahn, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Date ________________________________________________ __________________ Marguerite Rigoglioso, Ph.D., Committee Member Date Copyright © Hayley Jane Arrington 2012 All Rights Reserved Formatted according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th Edition ii Abstract Celtic Solar Goddesses: From Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven by Hayley J. Arrington Utilizing a feminist hermeneutical inquiry, my research through three Celtic goddesses—Aine, Grian, and Brigit—shows that the sun was revered as feminine in Celtic tradition. Additionally, I argue that through the introduction and assimilation of Christianity into the British Isles, the Virgin Mary assumed the same characteristics as the earlier Celtic solar deities. The lands generally referred to as Celtic lands include Cornwall in Britain, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Brittany in France; however, I will be limiting my research to the British Isles. I am examining these three goddesses in particular, in relation to their status as solar deities, using the etymologies of their names to link them to the sun and its manifestation on earth: fire. Given that they share the same attributes, I illustrate how solar goddesses can be equated with goddesses of sovereignty. Furthermore, I examine the figure of St. -

Pilgrimage Stories: the Farmer Fairy's Stone

PILGRIMAGE STORIES: THE FARMER FAIRY’S STONE By Betty Lou Chaika One of the primary intentions of our recent six-week pilgrimage, first to Scotland and then to Ireland, was to visit EarthSpirit sanctuaries in these ensouled landscapes. We hoped to find portals to the Otherworld in order to contact renewing, healing, transformative energies for us all, and especially for some friends with cancer. I wanted to learn how to enter the field of divinity, the aliveness of the EarthSpirit world’s interpenetrating energies, with awareness and respect. Interested in both geology and in our ancestors’ spiritual relationship with Rock, I knew this quest would involve a deeper meeting with rock beings in their many forms. When we arrived at a stone circle in southwest Ireland (whose Gaelic name means Edges of the Field) we were moved by the familiar experience of seeing that the circle overlooks a vast, beautiful landscape. Most stone circles seem to be in places of expansive power, part of a whole sacred landscape. To the north were the lovely Paps of Anu, the pair of breast-shaped hills, both over 2,000 feet high, named after Anu/Aine, the primary local fertility goddess of the region, or after Anu/Danu, ancient mother goddess of the supernatural beings, the Tuatha De Danann. The summits of both hills have Neolithic cairns, which look exactly like erect nipples. This c. 1500 BC stone circle would have drawn upon the power of the still-pervasive earlier mythology of the land as the Mother’s body. But today the tops of the hills were veiled in low, milky clouds, and we could only long for them to be revealed. -

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1 Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by William Butler Yeats This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry Author: William Butler Yeats Editor: William Butler Yeats Release Date: October 28, 2010 [EBook #33887] Language: English Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAIRY AND FOLK TALES *** Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Brian Foley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) FAIRY AND FOLK TALES OF THE IRISH PEASANTRY. EDITED AND SELECTED BY W. B. YEATS. THE WALTER SCOTT PUBLISHING CO., LTD. LONDON AND FELLING-ON-TYNE. NEW YORK: 3 EAST 14TH STREET. INSCRIBED TO MY MYSTICAL FRIEND, G. R. CONTENTS. THE TROOPING FAIRIES-- PAGE The Fairies 3 Frank Martin and the Fairies 5 The Priest's Supper 9 The Fairy Well of Lagnanay 13 Teig O'Kane and the Corpse 16 Paddy Corcoran's Wife 31 Cusheen Loo 33 The White Trout; A Legend of Cong 35 The Fairy Thorn 38 The Legend of Knockgrafton 40 A Donegal Fairy 46 CHANGELINGS-- The Brewery of Egg-shells 48 The Fairy Nurse 51 Jamie Freel and the Young Lady 52 The Stolen Child 59 THE MERROW-- -

Mary Condren, Th.D. Already, in the Run-Up to Hallowe'en, in Our Neighbourhoods Malevolent Forces Are at Work. Burnt out Cars

Mary Condren, Th.D. Already, in the run-up to Hallowe’en, in our neighbourhoods malevolent forces are at work. Burnt out cars, bangers, toxic fireworks, are encouraged by shopfront images: evil witches on broomsticks, or even Dracula, the emerging patron of Samhain in our time. Maybe it is time to revisit the Old Ways, and maybe even a Me-too Movement for Witches is long overdue? In Ireland, Samhain, (October 31st) today’s Hallowe’en, is traditionally associated with the figure of the Cailleach, whose traditions are beautifully recovered in Gearóid Ó Crualaoich’s book, The Book of the Cailleach. Along with her daughters, the cailleacha, sometimes known as goddesses, the Cailleach, dropping huge boulders from her cloak created the world — mountains, rivers, wells, and megalithic sites such as the Hill of the Witch at Lough Crew. Her mná feasa the Wise Ones of old Ireland continued her memories and traditions in ritual and song. However, in Old Irish classical literature, the Cailleach traditions are largely re-interpreted and inverted. Ongoing struggles against the Old Ways are reflected in the Book of the Gathering or Invasions. In the Dindshenchas (stories of how places got their names), cailleacha are drowned, gang-raped, or otherwise disposed of, often for going widdershins around the well as they drew on ancestral stores of inherited wisdom, medical intuition, and herbal cures. The 9th century, Lament of the Cailleach Beara, reflects the demise of the mná feasa the Wise Women, now colonised and decrepit. One of the last invaders to Ireland, the Sons of Mil (representing Hebrews and Christians) made a pact with the Tuatha dé Danann (People of the Goddess, Danu) whom they had defeated. -

The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal

The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal to the Land of the Living AN OLD IRISH SAGA NOW FIRST EDITED, WITH TRANSLATION, NOTES, AND GLOSSARY, BY Kuno Meyer London: Published by David Nutt in the Strand [1895] The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal to the Land of the Living Page 1 INTRODUCTION THE old-Irish tale which is here edited and fully translated 1 for the first time, has come down to us in seven MSS. of different age and varying value. It is unfortunate that the oldest copy (U), that contained on p. 121a of the Leabhar na hUidhre, a MS. written about 1100 A.D., is a mere fragment, containing but the very end of the story from lil in chertle dia dernaind (§ 62 of my edition) to the conclusion. The other six MSS. all belong to a much later age, the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries respectively. Here follow a list and description of these MSS.:-- By R I denote a copy contained in the well-known Bodleian vellum quarto, marked Rawlinson B. 512, fo. 119a, 1-120b, 2. For a detailed description of this codex, see the Rolls edition of the Tripartite Life, vol. i. pp. xiv.-xlv. As the folios containing the copy of our text belong to that portion of the MS. which begins with the Baile in Scáil (fo. 101a), it is very probable that, like this tale, they were copied from the lost book of Dubdálethe, bishop of p. viii [paragraph continues] Armagh from 1049 to 1064. See Rev. Celt. xi. -

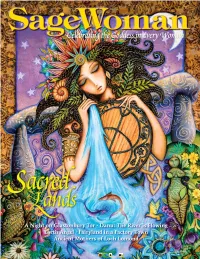

Sagewoman No

SageWoman No. 87 • Sacred Lands Cover1 BBIMEDIA.COM CRONEMAGAZINE.COM SAGEWOMAN.COM WITCHESANDPAGANS.COM BB Med a Magazines that feed your soul and liven your spirits. W & Navigation Controls Availability depends on the reader application. Previous Page Toggle Next Page Bookmarks First Page Last Page ©2014 BBI MEDIA INC . P O BOX 687 . FOREST GROVE . OR 97116 . USA . 503-430-8817 © 2015 Hrana Janto Hrana © 2015 By Jude Lally Artwork by Hrana Janto ncient and Helen O’Sullivan mothers of Loch lomond 8 A SageWoman No. 87 • Sacred Lands hen I was a child, my dad would take us the west until they reach the mountains and drop their rambling around the hills where we lived up life-giving rain. When Ben Lomond (“Ben” means above Loch Lomond, Scotland. Among the “mountain”) is obscured completely, veiled by heavily Wstones at the top of Carman Hill, I would sit ever so pregnant clouds dragging low on its slopes, you can quietly, scrunching up my eyes: in my imagination all easily feel that you are truly in between the worlds. the cars disappeared, and with a final blink, the streets and houses were rendered invisible as well. Then I would the Cailleach in Nature hold my breath, hoping I could see the Old Ones that Stuart McHardy recognizes the giantess archetype I knew lived there, the ones from the time before the of the Cailleach in a medieval poem, within the figure roads, and cars, and houses. Even though I never saw of ‘Gyre-Carolling,’ who is said to have formed Loch those ancient people, I felt the energies of the land, Lomond. -

The Mast of Macha: the Celtic Irish and the War Goddess of Ireland

Catherine Mowat: Barbara Roberts Memorial Book Prize Winner, 2003 THE 'MAST' OF MACHA THE CELTIC IRISH AND THE WAR GODDESS OF IRELAND "There are rough places yonder Where men cut off the mast of Macha; Where they drive young calves into the fold; Where the raven-women instigate battle"1 "A hundred generous kings died there, - harsh, heaped provisions - with nine ungentle madmen, with nine thousand men-at-arms"2 Celtic mythology is a brilliant shouting turmoil of stories, and within it is found a singularly poignant myth, 'Macha's Curse'. Macha is one of the powerful Morrigna - the bloody Goddesses of War for the pagan Irish - but the story of her loss in Macha's Curse seems symbolic of betrayal on two scales. It speaks of betrayal on a human scale. It also speaks of betrayal on a mythological one: of ancient beliefs not represented. These 'losses' connect with a proposal made by Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, in The Myth of The Goddess: Evolution of an Image, that any Goddess's inherent nature as a War Goddess reflects the loss of a larger, more powerful, image of a Mother Goddess, and another culture.3 This essay attempts to describe Macha and assess the applicability of Baring and Cashford's argument in this particular case. Several problems have arisen in exploring this topic. First, there is less material about Macha than other Irish Goddesses. Second, the fertile and unique synergy of cultural beliefs created by the Celts4 cannot be dismissed and, in a short paper, a problem exists in balancing what Macha meant to her people with the broader implications of the proposal made by Baring and Cashford. -

Discovery of the Tomb of Ollamh Fodhla (Ollv F¿La)

— DISCOVERY Of>THE TOMB OF [OUdv Fola)y IRELAND'S FAIMOUS MONARCH AND LAAV-:^IAKER UPWARDS OF THREE THOUSAND YEARS AGO. BY EUGENE ALFRED CONWELL, M.R.I. A., M.A.I., F.R.HiST. Soc, &c., INSPECTOR OF IRISH NATIONAL SCHOOLS. " That speechless past has begun to speak." Palgravk. M\i\ difty-su- pustralions. DUBLIN: M^GLASHAN & GILL, 50, UPPER SACKVILLE-STREET. LOJsDOX: WILLIAMS & KORGATE, HENRIETTA-ST,, COYENT GARDEN. EUINBURGH: EDMONSTON & DOUGLAS, PRINCE'S-ST. 1873. [.4// U'ujhta reserrej.] 3ft Of C76 DUBLIN PRINTED AT THK UNIVEKSITY PRESS, BY iM. H. GILL. BOSTON COLIEGE LIPRARY CHESTNUT HILL, MASS. PREFACE. jjOME portions of the following pages were originally contributed to the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy,* in a Paper read at a meeting of that body on 12th February, 1872, " On the Identification of the Ancient Cemetery at Loughcrew, Co. Meath, and the Discovery of the Tomb of Ollamh Fodhla." Our attempt to rescue from the domain of legend and romance the memories of a locality, at one time the most famous in our island, and in so doing to revive a faded and long forgotten page in early Irish History, is here presented to our fellow-country- men, in the hope that it may be found not only not uninterest- ing to them, but that it may be the means of inducing others, in various localities, to turn their attention to, and to elucidate whatever remains of Ireland's Ancient Relics may be still ex- tant in their respective vicinities. Our very grateful thanks are pre-eminently due to the late J. -

Sacred-Outcast-Lyrics

WHITE HORSES White horses white horses ride the wave Manannan Mac Lir makes love in the cave The seed of his sea foam caresses the sand enters her womb and makes love to the land Manannan Mac Lir God of the Sea deep calm and gentle rough wild and free deep calm and gentle rough wild and free Her bones call him to her twice a day the moon drives him forward then takes him away His team of white horses shake their manes unbridled and passionate he rides forth again Manannan Mac Lir God of the Sea deep calm and gentle rough wild and free deep calm and gentle rough wild and free he’s faithful he’s constant its time to rejoice the salt in his kisses gives strength to her voice the fertile Earth Mother yearns on his foam to enter her deeply make love to the Crone Manannan Mac Lir God of the Sea deep calm and gentle rough wild and free deep calm and gentle deep calm and gentle deep calm and gentle deep calm and gentle deep calm and gentle Rough wild and free BONE MOTHER Bone Bone Bone Bone Mother Bone Bone Bone Crone Crone Crone Crone Beira Crone Crone Crone, Cailleach She stirs her cauldron underground Cerridwen. TRIPLE GODDESS Bridghid, Bride, Bree, Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me Her fiery touch upon the frozen earth Releases the waters time for rebirth Bridghid Bride Bree Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me Her mantle awakens snowdrops first Her fire and her waters sprout life in the earth Bridghid Bride Bree Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me Imbolc is her season the coming of Spring Gifts of song and smithcraft and healing she brings Bridghid Bride Bree Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me SUN GOD LUGH In days of old the stories told of the Sun God Lugh Born…… of the Aes Dana, half Fomorian too Sun God Sun God Sun God Lugh From Kian’s seed and Ethlin’s womb Golden threads to light the moon A boy to grow in all the arts To dance with Bride within our hearts Hopeful vibrant a visionary sight Creative gifts shining bright. -

Lady Jane Wilde As the Celtic Sovereignty

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-12-01 Resurrecting Speranza: Lady Jane Wilde as the Celtic Sovereignty Heather Lorene Tolen Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Tolen, Heather Lorene, "Resurrecting Speranza: Lady Jane Wilde as the Celtic Sovereignty" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1642. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1642 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RESURRECTING SPERANZA: LADY JANE WILDE AS THE CELTIC SOVEREIGNTY by Heather L. Tolen A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English Brigham Young University December 2008 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Heather L. Tolen This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. ______________________________ ___________________________________ Date Claudia Harris, Chair ______________________________ ___________________________________ Date Dr. Leslee Thorne-Murphy ______________________________ ___________________________________ -

Appendixes Appendix A

APPENDIXES APPENDIX A Yeats's Notes in The Collected Poems, 1933 The Spelling of Gaelic Names In this edition of my poems I have adopted Lady Gregory's spelling of Gaelic names, with, I think, two exceptions. The 'd' of 'Edain' ran too well in my verse for me to adopt her perhaps more correct 'Etain,' and for some reason unknown to me I have always preferred 'Aengus' to her 'Angus.' In her Gods and Fighting Men and Cuchulain of Muirthemne she went as close to the Gaelic spelling as she could without making the names unpro nounceable to the average reader.'-1933. Crossways. The Rose (pages 3, 25) Many of the poems in Crossways, certainly those upon Indian subjects or upon shepherds and fauns, must have been written before I was twenty, for from the moment when I began The Wanderings of Oisin, which I did at that age, I believe, my subject-matter became Irish. Every time I have reprinted them I have considered the leaving out of most, and then remem bered an old school friend who has some of them by heart, for no better reason, as I think, than that they remind him of his own youth.' The little Indian dramatic scene was meant to be the first scene of a play about a man loved by two women, who had the one soul between them, the one woman waking when the other slept, and knowing but daylight as the other only night. It came into my head when I saw a man at Rosses Point carrying two salmon. -

Test Abonnement

L E X I C O N O F T H E W O R L D O F T H E C E L T I C G O D S Composed by: Dewaele Sunniva Translation: Dewaele Sunniva and Van den Broecke Nadine A Abandinus: British water god, but locally till Godmanchester in Cambridgeshire. Abarta: Irish god, member of the de Tuatha De Danann (‘people of Danu’). Abelio, Abelionni, Abellio, Abello: Gallic god of the Garonne valley in South-western France, perhaps a god of the apple trees. Also known as the sun god on the Greek island Crete and the Pyrenees between France and Spain, associated with fertility of the apple trees. Abgatiacus: ‘he who owns the water’, There is only a statue of him in Neumagen in Germany. He must accompany the souls to the Underworld, perhaps a heeling god as well. Abhean: Irish god, harpist of the Tuatha De Danann (‘people of Danu’). Abianius: Gallic river god, probably of navigation and/or trade on the river. Abilus: Gallic god in France, worshiped at Ar-nay-de-luc in Côte d’Or (France) Abinius: Gallic river god or ‘the defence of god’. Abna, Abnoba, Avnova: goddess of the wood and river of the Black Wood and the surrounding territories in Germany, also a goddess of hunt. Abondia, Abunciada, Habonde, Habondia: British goddess of plenty and prosperity. Originally she is a Germanic earth goddess. Accasbel: a member of the first Irish invasion, the Partholans. Probably an early god of wine. Achall: Irish goddess of diligence and family love.