Hyperplastic Polyp Or Sessile Serrated Lesion? the Contribution of Serial Sections to Reclassification Diana R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Patients with Dominantly Inherited Colorectal Cancer

Practice Parameters For The Treatment Of Patients With Dominantly Inherited Colorectal Cancer Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 2003;46(8):1001-1012 Prepared by: The Standards Task Force The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons James Church, MD; Clifford Simmang, MD; On Behalf of the Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Colorectal Cancer and the Standards Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to assuring high quality patient care by advancing the science, prevention, and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus. The standards committee is composed of Society members who are chosen because they have demonstrated expertise in the specialty of colon and rectal surgery. This Committee was created in order to lead international efforts in defining quality care for conditions related to the colon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied by developing Clinical Practice Guidelines based on the best available evidence. These guidelines are inclusive, and not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on which decisions can be made, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. These guidelines are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers, and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed by the topics covered in these guidelines. Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Patients With Dominantly Inherited Colorectal Cancer Inherited colorectal cancer includes two main syndromes in which predisposition to the disease is based on a germline mutation that may be transmitted from parent to child. -

Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal Version 2.2019 — August 8, 2019 NCCN.org Continue Version 2.2019, 08/08/19 © 2019 National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN. Printed by PEDRO ANTONIO PARRA BAOS on 11/18/2019 12:12:24 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2019 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved. NCCN Guidelines Index NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2019 Table of Contents Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal Discussion *Dawn Provenzale, MD, MS/Chair ¤ Þ Michael J. Hall, MD, MS † ∆ Arnold J. Markowitz, MD ¤ Duke Cancer Institute Fox Chase Cancer Center Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center *Samir Gupta, MD/Vice-chair ¤ Amy L. Halverson, MD ¶ Robert J. Mayer, MD † Þ UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Center of Northwestern University Cancer Center Dennis J. Ahnen, MD ¤ University of Colorado Cancer Center Stanley R. Hamilton, MD ≠ June Mikkelson, MS, CGC ∆ The University of Texas Roswell Park Cancer Institute Lee-May Chen, MD ¶ MD Anderson Cancer Center UCSF Helen Diller Family Reid M. Ness, MD, MPH ¤ Comprehensive Cancer Center Heather Hampel, MS, CGC ∆ Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center The Ohio State University Comprehensive Daniel C. Chung, MD ¤ ∆ Cancer Center - James Cancer Hospital Shajan Peter, MD ¤ Massachusetts General Hospital and Solove Research Institute O'Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center Cancer Center at UAB Sigurdis Haraldsdottir, MD, PhD † Gregory Cooper, MD ¤ Stanford Cancer Institute Scott E. -

Guidelines for the Management of Hereditary Colorectal Cancer

Guidelines Guidelines for the management of hereditary Gut: first published as 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319915 on 28 November 2019. Downloaded from colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/ United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG) Kevin J Monahan ,1,2 Nicola Bradshaw,3 Sunil Dolwani,4 Bianca Desouza,5 Malcolm G Dunlop,6 James E East,7,8 Mohammad Ilyas,9 Asha Kaur,10 Fiona Lalloo,11 Andrew Latchford,12 Matthew D Rutter ,13,14 Ian Tomlinson ,15,16 Huw J W Thomas,1,2 James Hill,11 Hereditary CRC guidelines eDelphi consensus group ► Additional material is ABSTRact having a family history of a first-degree relative published online only. To view Heritable factors account for approximately 35% of (FDR) or second degree relative (SDR) with CRC.2 please visit the journal online (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ colorectal cancer (CRC) risk, and almost 30% of the While highly penetrant syndromes such as Lynch gutjnl- 2019- 319915). population in the UK have a family history of CRC. syndrome (LS), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) The quantification of an individual’s lifetime risk of and other polyposis syndromes account for account For numbered affiliations see end of article. gastrointestinal cancer may incorporate clinical and for only 5–10% of all CRC diagnoses, advances molecular data, and depends on accurate phenotypic in genetic diagnosis, improvements in endoscopic Correspondence to assessment and genetic diagnosis. In turn this may surgical control, and medical and lifestyle interven- Dr Kevin J Monahan, Family facilitate targeted risk-reducing interventions, including tions provide opportunities for CRC prevention and Cancer Clinic, St Mark’s endoscopic surveillance, preventative surgery and effective treatment in susceptible individuals. -

Comparing Right Colon Adenoma and Hyperplastic Polyp

Title: Comparing right colon adenoma and hyperplastic polyp miss rate in colonoscopy using water exchange and carbon dioxide insufflation: A prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial NCT Number: 03845933 Unique Protocol ID: EGH-2019 Date: Feb 16, 2019 頁 1 / 10 INTRODUCTION Colonoscopy is currently regarded as the gold standard to detect and prevent colorectal cancer (CRC) [1]. It estimated to prevent about 76%-90% of CRC [2], but post-colonoscopy CRCs (PCCRCs) still occur. Recent case-control studies consistently demonstrated that protection by colonoscopy against right-sided colon cancer, ranging from 40% to 60%, was lower than the 80% protection attained in the left colon [3-5]. Of all PCCRCs, 58% were attributed to lesions missed during examination [6]. In a systematic review of tandem colonoscopy studies, a 22% pooled miss-rate for all polyps was reported [7]. Colonoscopy maneuvers helping to reduce miss-rate for all polyps, particularly in the right colon, have the potential to decrease the incidence of PCCRCs. Water exchange (WE) colonoscopy is characterized by the gasless insertion to the cecum in clear water and maximizing cleanliness during insertion. WE colonoscopy has been shown to improve the overall adenoma detection rate (ADR), compared to air insufflation colonoscopy, in many prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [8-13]. WE colonoscopy also has been shown to improve right colon ADR in RCTs [10-12] and meta-analyses [14,15]. In a pooled data from two multisite RCTs, WE also significantly increases right colon combined advanced and sessile serrated ADR as compared to air insufflation colonoscopy [16]. Decreased multitasking-related distraction from cleaning maneuvers has been the most recently identified explanation for the increase in ADR by WE [17]. -

Combined Endo-Laparoscopic Surgery for Difficult Benign Colorectal Polyps

485 Review Article (Current Strategies in Colon Cancer Management) Combined endo-laparoscopic surgery for difficult benign colorectal polyps Zhong-Hui Liu1, Li Jiang1, Fion Siu-Yin Chan1,2, Michael Ka-Wah Li3, Joe King-Man Fan1,2,3 1Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen 518053, China; 2Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; 3Asia-Pacific Endo-Lap Surgery Group (APELS), Hong Kong, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: JKM Fan, MKW Li; (II) Administrative support: MKW Li; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: FSY Chan; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: ZH Liu, L Jiang; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: ZH Liu; FSY Chan; JKM Fan; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Joe King-Man Fan, MBBS (HK), MS (HKU), FRCSEd, FACS. Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen 518053, China. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC) depends largely on the detection and removal of colorectal polyps. Despite the advances in endoscopic techniques, there are still a subgroup of polyps that cannot be treated purely by endoscopic approach, which comprise of about 10–15% of all the polyps. These so-called “difficult colorectal polyps” are polyps with large size, morphology, at difficult location, scarring or due to recurrence, which have historically been managed by surgical segmental resection. In treating benign difficult colorectal polyps, we have to balance the operative risks and morbidities associated with surgical segmental resection. Therefore, combined endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery (CELS) has been developed to remove this subgroup of difficult benign polyps. -

Polyp Classification from the Microscope

11/12/2019 OUTLINE Serrated lesions: • Updates on terminology Polyp classification from the • Updates on sessile serrated polyposis microscope HGD / intramucosal carcinoma / carcinoma in situ: • Clarify the terminology David F. Schaeffer, MD, FRCPC • Discuss diagnostic fears of pathologists Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, UBC The subtle polyp: Head, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Vancouver Coastal Health Pathology Lead, BCCA Colon Cancer Screening Program • Are some polyps really only hidden from the pathologist? • Do additional levels help? 3 January 2018 October 2019 OUTLINE WHY CARE ABOUT SERRATED POLYPS? Serrated lesions: FIT not useful • Updates on terminology • Updates on sessile serrated polyposis HGD / intramucosal carcinoma / carcinoma in situ: • Clarify the terminology • Discuss diagnostic fears of pathologists The subtle polyp: At best moderate • Are some polyps really only hidden from the agreement between pathologist? expert GI pathologist • Do additional levels help? October 2019 October 2019 1 11/12/2019 SIMPLIFIED VIEW OF SERRATED PATHWAY TYPES OF SERRATED POLYPS UNTIL JULY 2019 65% 30% 5% Important points Hyperplastic polyp (HP) Sessile Serrated Traditional Serrated • SSPs probably develop from MVHPs: MVHPs aren’t completely Microvesicular (MVHP) adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) Adenoma (TSA) innocuous but transformation to SSP is likely a rare event (occurs Goblet cell rich (GCHP ) more commonly in the right colon) • Serrated pathway is characterized by hypermethylation of -

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Polymnia Galiatsatos, M.D., F.R.C.P.(C),1 and William D

American Journal of Gastroenterology ISSN 0002-9270 C 2006 by Am. Coll. of Gastroenterology doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00375.x Published by Blackwell Publishing CME Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Polymnia Galiatsatos, M.D., F.R.C.P.(C),1 and William D. Foulkes, M.B., Ph.D.2 1Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, The Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and 2Program in Cancer Genetics, Departments of Oncology and Human Genetics, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal-dominant colorectal cancer syndrome, caused by a germline mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, on chromosome 5q21. It is characterized by hundreds of adenomatous colorectal polyps, with an almost inevitable progression to colorectal cancer at an average age of 35 to 40 yr. Associated features include upper gastrointestinal tract polyps, congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium, desmoid tumors, and other extracolonic malignancies. Gardner syndrome is more of a historical subdivision of FAP, characterized by osteomas, dental anomalies, epidermal cysts, and soft tissue tumors. Other specified variants include Turcot syndrome (associated with central nervous system malignancies) and hereditary desmoid disease. Several genotype–phenotype correlations have been observed. Attenuated FAP is a phenotypically distinct entity, presenting with fewer than 100 adenomas. Multiple colorectal adenomas can also be caused by mutations in the human MutY homologue (MYH) gene, in an autosomal recessive condition referred to as MYH associated polyposis (MAP). Endoscopic screening of FAP probands and relatives is advocated as early as the ages of 10–12 yr, with the objective of reducing the occurrence of colorectal cancer. -

3. Studies of Colorectal Cancer Screening

IARC HANDBOOKS COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING VOLUME 17 This publication represents the views and expert opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer-Preventive Strategies, which met in Lyon, 14–21 November 2017 LYON, FRANCE - 2019 IARC HANDBOOKS OF CANCER PREVENTION 3. STUDIES OF COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING 3.1 Methodological considerations end-point of the RCT can be the incidence of the cancer of interest. Methods for colorectal cancer (CRC) screen- The observed effect of screening in RCTs is ing include endoscopic methods and stool-based dependent on, among other things, the partic- tests for blood. The two primary end-points for ipation in the intervention group and the limi- endoscopic CRC screening are (i) finding cancer tation of contamination of the control group. at an early stage (secondary prevention) and Low participation biases the estimate of effect (ii) finding and removing precancerous lesions towards its no-effect value, and therefore it must (adenomatous polyps), to reduce the incidence be evaluated and reported. Screening of controls of CRC (primary prevention). The primary by services outside of the RCT also dilutes the end-point for stool-based tests is finding cancer effect of screening on CRC incidence and/or at an early stage. Stool-based tests also have some mortality. If the screening modality being eval- ability to detect adenomatous polyps; therefore, a uated is widely used in clinical practice in secondary end-point of these tests is reducing the the region or regions where the RCT is being incidence of CRC. conducted, then contamination may be consid- erable, although it may be difficult and/or costly 3.1.1 Randomized controlled trials of to estimate its extent. -

Molecular Classification of Patients with Unexplained Hamartomatous and Hyperplastic Polyposis

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Molecular Classification of Patients With Unexplained Hamartomatous and Hyperplastic Polyposis Kevin Sweet, MS, CGC Context Significant proportions of patients with hamartomatous polyposis or with Joseph Willis, MD hyperplastic/mixed polyposis remain without specific clinical and molecular diagnosis Xiao-Ping Zhou, MD, PhD or present atypically. Assigning a syndromic diagnosis is important because it guides management, especially surveillance and prophylactic surgery. Carol Gallione, PhD Objective To systematically classify patients with unexplained hamartomatous or hy- Takeshi Sawada, MD, PhD perplastic/mixed polyposis by extensive molecular analysis in the context of central Pia Alhopuro, MD rereview of histopathology results. Sok Kean Khoo, PhD Design, Setting, and Patients Prospective, referral-based study of 49 unrelated patients from outside institutions (n=28) and at a comprehensive cancer center (n=21), Attila Patocs, MD, PhD conducted from May 2, 2002, until December 15, 2004. Germline analysis of PTEN, Cossette Martin, PhD BMPR1A, STK11 (sequence, deletion), SMAD4, and ENG (sequence), specific exon screen- Scott Bridgeman, BSc ing of BRAF, MYH, and BHD, and rereview of polyp histology results were performed. John Heinz, PhD Main Outcome Measures Molecular, clinical, and histopathological findings in pa- tients with unexplained polyposis. Robert Pilarski, MS, CGC Results Of the 49 patients, 11 (22%) had germline mutations. Of 14 patients with Rainer Lehtonen, BSc juvenile polyposis, 2 with early-onset disease had mutations in ENG, encoding endo- Thomas W. Prior, PhD glin, previously only associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; 1 had hemi- zygous deletion encompassing PTEN and BMPR1A; and 1 had an SMAD4 mutation. Thierry Frebourg, MD, PhD One individual previously classified with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome had a PTEN dele- Bin Tean Teh, MD, PhD tion. -

An “Expressionistic” Look at Serrated Precancerous Colorectal Lesions Giancarlo Marra

Marra Diagnostic Pathology (2021) 16:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-01064-1 RESEARCH Open Access An “expressionistic” look at serrated precancerous colorectal lesions Giancarlo Marra Abstract Background: Approximately 60% of colorectal cancer (CRC) precursor lesions are the genuinely-dysplastic conventional adenomas (cADNs). The others include hyperplastic polyps (HPs), sessile serrated lesions (SSL), and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs), subtypes of a class of lesions collectively referred to as “serrated.” Endoscopic and histologic differentiation between cADNs and serrated lesions, and between serrated lesion subtypes can be difficult. Methods: We used in situ hybridization to verify the expression patterns in CRC precursors of 21 RNA molecules that appear to be promising differentiation markers on the basis of previous RNA sequencing studies. Results: SSLs could be clearly differentiated from cADNs by the expression patterns of 9 of the 12 RNAs tested for this purpose (VSIG1, ANXA10, ACHE, SEMG1, AQP5, LINC00520, ZIC5/2, FOXD1, NKD1). Expression patterns of all 9 in HPs were similar to those in SSLs. Nine putatively HP-specific RNAs were also investigated, but none could be confirmed as such: most (e.g., HOXD13 and HOXB13), proved instead to be markers of the normal mucosa in the distal colon and rectum, where most HPs arise. TSAs displayed mixed staining patterns reflecting the presence of serrated and dysplastic glands in the same lesion. Conclusions: Using a robust in situ hybridization protocol, we identified promising tissue-staining markers that, if validated in larger series of lesions, could facilitate more precise histologic classification of CRC precursors and, consequently, more tailored clinical follow-up of their carriers. -

Appendix Lesions

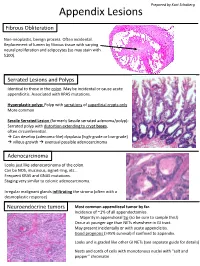

Prepared by Kurt Schaberg Appendix Lesions Fibrous Obliteration Non-neoplastic, benign process. Often incidental. Replacement of lumen by fibrous tissue with varying neural proliferation and adipocytes (so may stain with S100). Serrated Lesions and Polyps Identical to those in the colon. May be incidental or cause acute appendicitis. Associated with KRAS mutations. Hyperplastic polyp: Polyp with serrations of superficial crypts only More common Sessile Serrated Lesion (formerly Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp): Serrated polyp with distortion extending to crypt bases, often circumferential. → Can develop (adenoma-like) dysplasia (high-grade or low-grade) → villous growth → eventual possible adenocarcinoma Adenocarcinoma Looks just like adenocarcinoma of the colon. Can be NOS, mucinous, signet-ring, etc… Frequent KRAS and GNAS mutations. Staging very similar to colonic adenocarcinoma. Irregular malignant glands infiltrating the stroma (often with a desmoplastic response) Neuroendocrine tumors Most common appendiceal tumor by far. Incidence of ~1% of all appendectomies. Majority in appendiceal tip (so be sure to sample this!) Occur at younger age than NETs elsewhere in GI tract. May present incidentally or with acute appendicitis. Good prognosis (>95% survival) if confined to appendix. Looks and is graded like other GI NETs (see separate guide for details) Nests and cords of cells with monotonous nuclei with “salt and pepper” chromatin Unique Appendiceal Lesions Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms Low-grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (LAMN): -

Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines 2020

Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines 2020 Released 2020 health.govt.nz Citation: Ministry of Health. 2020. Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Published in September 2020 by the Ministry of Health PO Box 5013, Wellington 6140, New Zealand ISBN 978-1-99-002937-0 (online) HP 7469 This document is available at health.govt.nz This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. In essence, you are free to: share ie, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format; adapt ie, remix, transform and build upon the material. You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the licence and indicate if changes were made. Contents Introduction 1 Purpose of this advice 3 Audience for these guidelines 3 Associated documents 4 Equity 4 Clinical advice 5 High-risk polyps 6 Notes on clinical context 6 Definitions 7 High-quality colonoscopy in New Zealand 7 Serrated polyposis syndrome 7 High-quality polypectomy 8 Multiple Adenoma referral criteria to the New Zealand Familial Gastrointestinal Cancer Service 8 Boston Bowel Preparation Scale 9 UPDATE ON POLYP SURVEILLANCE GUIDELINES iii Introduction Te Aho o Te Kahu (the Cancer Control Agency) in partnership with the National Screening Unit, Ministry of Health endorses this advice on surveillance colonoscopy for follow-up after removal of polyps. This advice sets out appropriate practice for clinicians to follow subject to their own judgement. It has been developed to help them make decisions in this area. The advice was developed to align with recent publications from the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and Europe.1,2,3,4 These publications, based on updated available evidence up to June 2019, indicated that previous guidelines would now recommend over surveillance for some groups.