Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for the Management of Hereditary Colorectal Cancer

Guidelines Guidelines for the management of hereditary Gut: first published as 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319915 on 28 November 2019. Downloaded from colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/ United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG) Kevin J Monahan ,1,2 Nicola Bradshaw,3 Sunil Dolwani,4 Bianca Desouza,5 Malcolm G Dunlop,6 James E East,7,8 Mohammad Ilyas,9 Asha Kaur,10 Fiona Lalloo,11 Andrew Latchford,12 Matthew D Rutter ,13,14 Ian Tomlinson ,15,16 Huw J W Thomas,1,2 James Hill,11 Hereditary CRC guidelines eDelphi consensus group ► Additional material is ABSTRact having a family history of a first-degree relative published online only. To view Heritable factors account for approximately 35% of (FDR) or second degree relative (SDR) with CRC.2 please visit the journal online (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ colorectal cancer (CRC) risk, and almost 30% of the While highly penetrant syndromes such as Lynch gutjnl- 2019- 319915). population in the UK have a family history of CRC. syndrome (LS), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) The quantification of an individual’s lifetime risk of and other polyposis syndromes account for account For numbered affiliations see end of article. gastrointestinal cancer may incorporate clinical and for only 5–10% of all CRC diagnoses, advances molecular data, and depends on accurate phenotypic in genetic diagnosis, improvements in endoscopic Correspondence to assessment and genetic diagnosis. In turn this may surgical control, and medical and lifestyle interven- Dr Kevin J Monahan, Family facilitate targeted risk-reducing interventions, including tions provide opportunities for CRC prevention and Cancer Clinic, St Mark’s endoscopic surveillance, preventative surgery and effective treatment in susceptible individuals. -

Polyp Classification from the Microscope

11/12/2019 OUTLINE Serrated lesions: • Updates on terminology Polyp classification from the • Updates on sessile serrated polyposis microscope HGD / intramucosal carcinoma / carcinoma in situ: • Clarify the terminology David F. Schaeffer, MD, FRCPC • Discuss diagnostic fears of pathologists Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, UBC The subtle polyp: Head, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Vancouver Coastal Health Pathology Lead, BCCA Colon Cancer Screening Program • Are some polyps really only hidden from the pathologist? • Do additional levels help? 3 January 2018 October 2019 OUTLINE WHY CARE ABOUT SERRATED POLYPS? Serrated lesions: FIT not useful • Updates on terminology • Updates on sessile serrated polyposis HGD / intramucosal carcinoma / carcinoma in situ: • Clarify the terminology • Discuss diagnostic fears of pathologists The subtle polyp: At best moderate • Are some polyps really only hidden from the agreement between pathologist? expert GI pathologist • Do additional levels help? October 2019 October 2019 1 11/12/2019 SIMPLIFIED VIEW OF SERRATED PATHWAY TYPES OF SERRATED POLYPS UNTIL JULY 2019 65% 30% 5% Important points Hyperplastic polyp (HP) Sessile Serrated Traditional Serrated • SSPs probably develop from MVHPs: MVHPs aren’t completely Microvesicular (MVHP) adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) Adenoma (TSA) innocuous but transformation to SSP is likely a rare event (occurs Goblet cell rich (GCHP ) more commonly in the right colon) • Serrated pathway is characterized by hypermethylation of -

3. Studies of Colorectal Cancer Screening

IARC HANDBOOKS COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING VOLUME 17 This publication represents the views and expert opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer-Preventive Strategies, which met in Lyon, 14–21 November 2017 LYON, FRANCE - 2019 IARC HANDBOOKS OF CANCER PREVENTION 3. STUDIES OF COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING 3.1 Methodological considerations end-point of the RCT can be the incidence of the cancer of interest. Methods for colorectal cancer (CRC) screen- The observed effect of screening in RCTs is ing include endoscopic methods and stool-based dependent on, among other things, the partic- tests for blood. The two primary end-points for ipation in the intervention group and the limi- endoscopic CRC screening are (i) finding cancer tation of contamination of the control group. at an early stage (secondary prevention) and Low participation biases the estimate of effect (ii) finding and removing precancerous lesions towards its no-effect value, and therefore it must (adenomatous polyps), to reduce the incidence be evaluated and reported. Screening of controls of CRC (primary prevention). The primary by services outside of the RCT also dilutes the end-point for stool-based tests is finding cancer effect of screening on CRC incidence and/or at an early stage. Stool-based tests also have some mortality. If the screening modality being eval- ability to detect adenomatous polyps; therefore, a uated is widely used in clinical practice in secondary end-point of these tests is reducing the the region or regions where the RCT is being incidence of CRC. conducted, then contamination may be consid- erable, although it may be difficult and/or costly 3.1.1 Randomized controlled trials of to estimate its extent. -

An “Expressionistic” Look at Serrated Precancerous Colorectal Lesions Giancarlo Marra

Marra Diagnostic Pathology (2021) 16:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-01064-1 RESEARCH Open Access An “expressionistic” look at serrated precancerous colorectal lesions Giancarlo Marra Abstract Background: Approximately 60% of colorectal cancer (CRC) precursor lesions are the genuinely-dysplastic conventional adenomas (cADNs). The others include hyperplastic polyps (HPs), sessile serrated lesions (SSL), and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs), subtypes of a class of lesions collectively referred to as “serrated.” Endoscopic and histologic differentiation between cADNs and serrated lesions, and between serrated lesion subtypes can be difficult. Methods: We used in situ hybridization to verify the expression patterns in CRC precursors of 21 RNA molecules that appear to be promising differentiation markers on the basis of previous RNA sequencing studies. Results: SSLs could be clearly differentiated from cADNs by the expression patterns of 9 of the 12 RNAs tested for this purpose (VSIG1, ANXA10, ACHE, SEMG1, AQP5, LINC00520, ZIC5/2, FOXD1, NKD1). Expression patterns of all 9 in HPs were similar to those in SSLs. Nine putatively HP-specific RNAs were also investigated, but none could be confirmed as such: most (e.g., HOXD13 and HOXB13), proved instead to be markers of the normal mucosa in the distal colon and rectum, where most HPs arise. TSAs displayed mixed staining patterns reflecting the presence of serrated and dysplastic glands in the same lesion. Conclusions: Using a robust in situ hybridization protocol, we identified promising tissue-staining markers that, if validated in larger series of lesions, could facilitate more precise histologic classification of CRC precursors and, consequently, more tailored clinical follow-up of their carriers. -

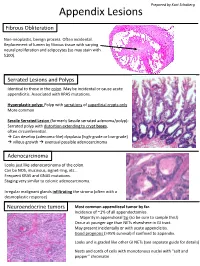

Appendix Lesions

Prepared by Kurt Schaberg Appendix Lesions Fibrous Obliteration Non-neoplastic, benign process. Often incidental. Replacement of lumen by fibrous tissue with varying neural proliferation and adipocytes (so may stain with S100). Serrated Lesions and Polyps Identical to those in the colon. May be incidental or cause acute appendicitis. Associated with KRAS mutations. Hyperplastic polyp: Polyp with serrations of superficial crypts only More common Sessile Serrated Lesion (formerly Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp): Serrated polyp with distortion extending to crypt bases, often circumferential. → Can develop (adenoma-like) dysplasia (high-grade or low-grade) → villous growth → eventual possible adenocarcinoma Adenocarcinoma Looks just like adenocarcinoma of the colon. Can be NOS, mucinous, signet-ring, etc… Frequent KRAS and GNAS mutations. Staging very similar to colonic adenocarcinoma. Irregular malignant glands infiltrating the stroma (often with a desmoplastic response) Neuroendocrine tumors Most common appendiceal tumor by far. Incidence of ~1% of all appendectomies. Majority in appendiceal tip (so be sure to sample this!) Occur at younger age than NETs elsewhere in GI tract. May present incidentally or with acute appendicitis. Good prognosis (>95% survival) if confined to appendix. Looks and is graded like other GI NETs (see separate guide for details) Nests and cords of cells with monotonous nuclei with “salt and pepper” chromatin Unique Appendiceal Lesions Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms Low-grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (LAMN): -

Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines 2020

Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines 2020 Released 2020 health.govt.nz Citation: Ministry of Health. 2020. Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Published in September 2020 by the Ministry of Health PO Box 5013, Wellington 6140, New Zealand ISBN 978-1-99-002937-0 (online) HP 7469 This document is available at health.govt.nz This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. In essence, you are free to: share ie, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format; adapt ie, remix, transform and build upon the material. You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the licence and indicate if changes were made. Contents Introduction 1 Purpose of this advice 3 Audience for these guidelines 3 Associated documents 4 Equity 4 Clinical advice 5 High-risk polyps 6 Notes on clinical context 6 Definitions 7 High-quality colonoscopy in New Zealand 7 Serrated polyposis syndrome 7 High-quality polypectomy 8 Multiple Adenoma referral criteria to the New Zealand Familial Gastrointestinal Cancer Service 8 Boston Bowel Preparation Scale 9 UPDATE ON POLYP SURVEILLANCE GUIDELINES iii Introduction Te Aho o Te Kahu (the Cancer Control Agency) in partnership with the National Screening Unit, Ministry of Health endorses this advice on surveillance colonoscopy for follow-up after removal of polyps. This advice sets out appropriate practice for clinicians to follow subject to their own judgement. It has been developed to help them make decisions in this area. The advice was developed to align with recent publications from the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and Europe.1,2,3,4 These publications, based on updated available evidence up to June 2019, indicated that previous guidelines would now recommend over surveillance for some groups. -

What's New in GI (PDF)

WHAT’S NEW IN PATHOLOGY? Issue 12 || February 2020 on “other tumors” covering mucosal • High grade appendiceal mucinous melanoma, germ cell tumors and neoplasm (HAMN) is added as a THE LATEST metastases. diagnostic entity similar to LAMN but showing high grade dysplasia. NEWS IN GI • Goblet cell carcinoid is renamed By Raul S. Gonzalez, M.D. Esophagus goblet cell adenocarcinoma, with • Gastroesophageal junction a new grading system. High grade examples represent what was he 5th Edition of the WHO Clas- carcinomas have been incorporated into the esophagus chapter. previously termed “adenocarcinoma Tsification of Tumours: Digestive ex goblet cell carcinoid” (Figure 1). System Tumours “blue book” was • Undifferentiated carcinoma is released in mid-2019. Key updates separated into its own entity rather are below. than a squamous cell carcinoma subtype. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma is considered a subtype of General updates this entity. • The classification of digestive neuro- endocrine neoplasms is revised. They are categorized as neuroendocrine Stomach tumors (NETs, formerly “carcinoids”) • Undifferentiated carcinoma is now or neuroendocrine carcinomas its own separate entity with many (NECs) based primarily on histology. subtypes (large cell carcinoma with • NETs can be grade 1, 2 or 3, with rhabdoid phenotype, pleomorphic Figure 1: Goblet cell carcinoid of a Ki67 of less than 3% qualifying as the appendix is renamed goblet cell carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma adenocarcinoma. grade 1 (formerly 0 - 2%). Mitotic and carcinoma with osteoclast-like rate is counted per 2 mm2, not per 10 giant cells). • Tubular carcinoid and L-cell high power fields. • Micropapillary adenocarcinoma carcinoid are renamed tubular NET • NECs are always high grade and is added as an aggressive subtype of and L-cell NET, respectively. -

Colon Polyps Prepared by Kurt Schaberg

Colon Polyps Prepared by Kurt Schaberg “Picket fence” nuclei: Elongated, Pencillate, pseudostratified, hyperchromatic Adenoma Nuclei retain basal orientation (bottom 1/2 of cell) Low grade dysplastic changes should involve at least the upper half of the crypts and the luminal surface Tubular Tubulovillous Villous Tubules >75% 25-75% <25% High-grade dysplasia (“carcinoma in situ”) Villi <25% 25-75% >75% Significant cytologic pleomorphism Rounded, heaped-up cells, ↑ nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio Nuclei: “Open” chromatin, prominent nucleoli Lose basal orientation, extend to luminal half of cell Architectural complexity Cribriforming, solid nests, intraluminal necrosis Absence of definite breach of basement membrane Intramucosal Carcinoma Neoplastic cells through basement membrane Into lamina propria but not through muscularis mucosae Single cell infiltration, small and irregular/angulated tubules Marked expansion of back-to-back cribriform glands No metastatic risk (paucity of lymphatics in colonic mucosa) Invasion into submucosa → implied by Desmoplastic response Chromosomal Instability Pathway (most common): APC → KRAS→ p53 (also often β-Catenin and SMAD4) Lynch Microsatellite Instability Pathway: Germline MMR mutation → Loss of heterozygosity → Microsatellite instability Serrated Polyps Hyperplastic polyp (HP): Superficial mucosal outgrowth characterized by elongated crypts lined by nondysplastic epithelium with surface papillary infoldings → serrated luminal contour (like a knife) Sessile serrated lesion (SSL): (formerly sessile serrated -

Download Download

JOURNAL OF THE ITALIAN SOCIETY OF ANATOMIC PATHOLOGY AND DIAGNOSTIC CYTOPATHOLOGY, ITALIAN DIVISION OF THE INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY OF PATHOLOGY Periodico trimestrale - Aut. Trib. di Genova n. 75 del 22/06/1949 ISSN: 1591-951X (Online) The GIPAD handbook of the gastrointestinal pathologist (in the Covid-19 era) - Part II 01VOL. 113 Edited by Paola Parente and Matteo Fassan FEBRUARY 2021 Editor-in-Chief C. Doglioni G. Pelosi M. Barbareschi San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan University of Milan Service of Anatomy and M. Fassan F. Pierconti University of Padua Pathological Histology, Trento Catholic University of Sacred G. Fornaciari Heart, Rome Associate Editor University of Pisa M. Chilosi M.P. Foschini S. Pileri Department of Pathology, Verona Bellaria Hospital, Bologna Milano European Institute of University, Verona G. Fraternali Orcioni Oncology, Milan S. Croce e Carle Hospital, Cuneo 01Vol. 113 P. Querzoli Managing Editor E. Fulcheri St Anna University Hospital, Ferrara University of Genoa February 2021 P. N oz za L. Resta M. Guido Pathology Unit, Ospedali Galliera, University of Bari Genova, Italy University of Padua S. Lazzi G. Rindi Catholic University of Sacred Italian Scientific Board University of Siena L. Leoncini M. Brunelli Heart, Rome University of Siena E.D. Rossi University of Verona C. Luchini G. Bulfamante Catholic University of Sacred University of Verona University of Milano G. Magro Heart, Rome G. Cenacchi University of Catania A.G. Rizzo University of Bologna E. Maiorano “Villa Sofia-Cervello” Hospital, C. Clemente University of Bari Aldo Moro Palermo San Donato Hospital, Milano A. Marchetti G. Rossi M. Colecchia University of Chieti-Pescara Hospital S. -

Evolving Pathologic Concepts of Serrated Lesions of the Colorectum

Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine 2020; 54: 276-289 https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2020.04.15 REVIEW Evolving pathologic concepts of serrated lesions of the colorectum Jung Ho Kim1,2, Gyeong Hoon Kang1,2 1Department of Pathology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul; 2Laboratory of Epigenetics, Cancer Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Here, we provide an up-to-date review of the histopathology and molecular pathology of serrated colorectal lesions. First, we introduce the updated contents of the 2019 World Health Organization classification for serrated lesions. The sessile serrated lesion (SSL) is a new diagnostic terminology that replaces sessile serrated adenoma and sessile serrated polyp. The diagnostic criteria for SSL were revised to require only one unequivocal distorted serrated crypt, which is sufficient for diagnosis. Unclassified serrated adenomas have been -in cluded as a new category of serrated lesions. Second, we review ongoing issues concerning the morphology of serrated lesions. Minor morphologic variants with distinct molecular features were recently defined, including serrated tubulovillous adenoma, mucin-rich vari- ant of traditional serrated adenoma (TSA), and superficially serrated adenoma. In addition to intestinal dysplasia and serrated dysplasia, minimal deviation dysplasia and not otherwise specified dysplasia were newly suggested as dysplasia subtypes of SSLs. Third, we summarize the molecular features of serrated lesions. The critical determinant of CpG island methylation development in SSLs is patient age. Interestingly, there may be ethnic differences in BRAF/KRAS mutation frequencies in SSLs. The molecular pathogenesis of TSAs is divided into KRAS and BRAF mutation pathways. -

Importance of Sessile Serrated Lesions in a Patient with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-021-01498-0 CASE REPORT Importance of sessile serrated lesions in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis Motoki Watanabe1 · Hideki Ishikawa1 · Shingo Ishiguro2 · Michihiro Mutoh1 Received: 16 May 2021 / Accepted: 6 August 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract A 28-year-old male visited hospital because his mother had been diagnosed with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) with a pathological variant of the APC gene. Total colonoscopy showed that he has more than 100 polyps distributed throughout the colorectum, and the APC gene variant was also detected. After he was diagnosed with FAP, he received information that surgery was currently the only way to prevent the development of colorectal cancer. However, he frmly declined to undergo surgical procedures and decided to have strict follow-up with frequent endoscopic polypectomy to prevent the development of colorectal cancer. At the frst endoscopy, polypectomy was performed on 52 polyps. Histological analysis of the dissected polyps showed that they were all adenomas, but adenocarcinoma was not detected. The second endoscopic polypectomy was performed after 4 months later. We found a pale 20 mm wide fat, elevated type polyp in the ascending colon with an adherent mucus cap that was resistant to washing of. After endoscopic mucosal resection, histological analysis revealed that there were two lesions in the polyps, a sessile serrated lesion (SSL) and SSL with dysplasia. SSL is a high-risk lesion for colorectal cancer, but it was reported to be rare in patients with FAP, and the existence of SSL suggested another car- cinogenesis pathway in patients with FAP in addition to the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. -

Hyperplastic Polyp Or Sessile Serrated Lesion? the Contribution of Serial Sections to Reclassification Diana R

Jaravaza and Rigby Diagnostic Pathology (2020) 15:140 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-01057-0 RESEARCH Open Access Hyperplastic polyp or sessile serrated lesion? The contribution of serial sections to reclassification Diana R. Jaravaza1* and Jonathan M. Rigby1,2 Abstract Background: The histological discrimination of hyperplastic polyps from sessile serrated lesions can be difficult. Sessile serrated lesions and hyperplastic polyps are types of serrated polyps which confer different malignancy risks, and surveillance intervals, and are sometimes difficult to discriminate. Our aim was to reclassify previously diagnosed hyperplastic polyps as sessile serrated lesions or confirmed hyperplastic polyps, using additional serial sections. Methods: Clinicopathological data for all colorectal hyperplastic polyps diagnosed in 2016 and 2017 was collected. The slides were reviewed and classified as hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated lesion, or other, using current World Health Organization criteria. Eight additional serial sections were performed for the confirmed hyperplastic polyp group and reviewed. Results: Of an initial 147 hyperplastic polyps from 93 patients, 9 (6.1%) were classified as sessile serrated lesions, 103 as hyperplastic polyps, and 35 as other. Of the 103 confirmed hyperplastic polyps, 7 (6.8%) were proximal, and 8 (7.8%) had a largest fragment size of ≥5 mm and < 10 mm. After 8 additional serial sections, 11 (10.7%) were reclassified as sessile serrated lesions. They were all less than 5 mm and represented 14.3% of proximal polyps and 10.4% of distal polyps. An average of 3.6 serial sections were required for a change in diagnosis. Conclusion: Histopathological distinction between hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated lesions remains a challenge.