Landman ACTA LAYAUT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discinisca Elslooensis Sp. N. Conglomerate

bulletin de l'institut royal des sciences naturelles de belgique sciences de la terre, 73: 185-194, 2003 bulletin van het koninklijk belgisch instituut voor natuurwetenschappen aardwetenschappen, 73: 185-194, 2003 Bosquet's (1862) inarticulate brachiopods: Discinisca elslooensis sp. n. from the Elsloo Conglomerate by Urszula RADWANSKA & Andrzej RADWANSKI Radwanska, U. & Radwanski, A., 2003. Bosquet's (1862) inarticu¬ Introduction late brachiopods: Discinisca elslooensis sp. n. from the Elsloo Con¬ glomerate. Bulletin de l'Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Bel¬ gique, Sciences de la Terre, 73: 185-194, 2 pis.; Bruxelles-Brussel, The present authors, during research on fossil repré¬ March 31, 2003. - ISSN 0374-6291 sentatives of the inarticulate brachiopods of the genus Discinisca Dall, 1871, from the Miocene of Poland (Radwanska & Radwanski, 1984), Oligocène of Austria (Radwanska & Radwanski, Abstract 1989), and topmost Cretac- eous of Poland (Radwanska & Radwanski, 1994), have been informed A revision of the Bosquet (1862) collection of inarticulate brachio¬ by Annie V. Dhondt, that well preserved pods, acquired about 140 years ago by the Royal Belgian Institute of material of these invertebrates from the original collec¬ Natural Sciences, shows that the whole collection, from the Elsloo tion of Bosquet (1862) has been acquired by the Royal Conglomerate, contains taxonomically conspecific material, despite its variable labelling and taxonomie interprétation by previous authors. Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in 1878. Annie V. The morphological features of complete shells, primarily of their Dhondt has kindly invited the present authors to revise ventral valves, clearly indicate that these inarticulate brachiopods this material to estimate its value and significance within can be well accommodated within the genus Discinisca Dall, 1871. -

A New Species of Inarticulate Brachiopods, Discinisca Zapfei Sp.N., from the Upper Triassic Zlambach Formation

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien Jahr/Year: 2001 Band/Volume: 102A Autor(en)/Author(s): Radwanski Andrzej, Summesberger Herbert Artikel/Article: A new species of inarticulate brachiopods, Discinisca zapfei sp.n., from the Upper Triassic Zlambach Formation (Northern Calcareous Alps, Austria), and a discussion of other Triassic disciniscans 109-129 ©Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 102 A 109–129 Wien, Februar 2001 A new species of inarticulate brachiopods, Discinisca zapfei sp.n., from the Upper Triassic Zlambach Formation (Northern Calcareous Alps, Austria), and a discussion of other Triassic disciniscans by Andrzej RADWANSKI1 & Herbert SUMMESBERGER2 (With 1 text-figure and 2 plates) Manuscript submitted on June 6th 2000, the revised manuscript on October 31st 2000. Abstract A new species of inarticulate brachiopods, Discinisca zapfei sp.n., is established for specimens collected by the late Professor Helmuth ZAPFE from the Zlambach Formation (Upper Triassic, Norian to Rhaetian) of the Northern Calcareous Alps (Austria). The collection, although small, offers a good insight into the morpho- logy of both the dorsal and the brachial valve of the shells, as well as into their mode of growth in clusters. The primary shell coloration is preserved, probably due to a rapid burial (? tempestite) of the clustered brachiopods in the living stage. A review and/or re-examination of other Triassic disciniscan brachiopods indicates that the newly established species, Discinisca zapfei sp.n., is closer to certain Paleogene-Neogene and/or present-day species than to any of the earlier described Triassic forms. -

A New Species of Inarticulate Brachiopods, Discinisca Steiningeri Sp

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien Jahr/Year: 1989 Band/Volume: 90A Autor(en)/Author(s): Radwanska Urszula, Radwanski Andrzej Artikel/Article: A new species of inarticulate brachiopods, Discinisca steiningeri sp. nov., from the Oligocene (Egerian) of Plesching near Linz, Austria 67-82 ©Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 90 A 67-82 Wien, Jänner 1989 A new species of inarticulate brachiopods, Discinisca steiningeri sp. nov., from the Late Oligocene (Egerian) of Plesching near Linz, Austria By U. RADWANSKA1) & A. RADWANSKI1) (With 2 textfigures and 4 plates) Manuscript submitted on January 21, 1988 Abstract A new species of inarticulate brachiopods, Discinisca steiningeri sp. n., is established for the specimens occurring in the Linz Sands (Egerian stage) exposed at Plesching near Linz, Austria. A relatively rich material of isolated dorsal valves allows the morphological variability of the new species to be recognized and to be compared with that known in other species of the genus, both modern and ancient. The specific characters of the new species are similar to some modern species of Discinisca which are typical of the western hemisphere but as yet unknown in the Tertiary deposits of Europe. A comparison with the few other species reported from the Miocene deposits of the Vienna Basin and the Fore-Carpathian Depression shows the distinctness of the new species from the remaining phyletic stocks, which are represented by occasional occurrences of the genus in the ancient sea systems of Central Europe. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS PART OF VOLUME LIII CAMBRIAN GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY No. 4.-CLASS1F1CAT10N AND TERMINOLOGY OF THE CAMBRIAN BRACHIOPODA With Two Plates BY CHARLES D. WALCOTT No. 1811 CITY OF WASHINGTON published by the smithsonian institution October 13, 1908] CAMBRIAN GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY No. 4.—CLASSIFICATION AND TERAIINOLOGY OF THE CAMBRIAN BRACHIOPODA^ By CHARLES D. WALCOTT (With Two Plates) CONTENTS Page Introduction i.^g Schematic diagram of evclution 139 Development in Cambrian time 141 Scheme of classification 141 Structure of the shell 149 Microscopic structure of the Cambrian Brachiopcda 150 Terminology relating to the shell 153 Definitions 154 INTRODUCTION My study of the Cambrian Brachiopoda has advanced so far that it is decided to pubHsh, in advance of the monograph,- a brief out- Hne of the classification, accompanied by (a) a schematic diagram of evolution and scheme of classification; (&) a note, with a diagram, on the development in Cambrian time; (c) a note on the structural characters of the shell, as this profoundly affects the classification; and (d) a. section on the terminology used in the monograph. The monograph, illustrated by 104 quarto plates and numerous text fig- ures, should be ready for distribution in the year 1909. SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM OF EVOLUTION In order to formulate, as far as possible, in a graphic manner a conception of the evolution and lines of descent of the Cambrian Brachiopoda, a schematic diagram (see plate 11) has been prepared for reference. It is necessarily tentative and incomplete, but it will serve to point out my present conceptions of the lines of evolution of the various genera, and it shows clearly the very rapid development of the primitive Atrematous genera in early Cambrian time. -

The Molluscan Fauna of the Alum Bluff Group of Florida Part V

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR THE MOLLUSCAN FAUNA OF THE ALUM BLUFF GROUP OF FLORIDA PART V. TELLINACEA, SOLENACEA, MACTRACEA MYACEA, MOLLUSCOIDEA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 142-E Please do not destroy or throw away this publication. If you have no further use for it, write to the Geological Survey at Washington and ask for a frank to return it DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Hubert Work, Secretary U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY George Otis Smith, Director Professional Paper 142 E THE MOLLUSGAN FAUNA OF THE ALUM BLUFF GROUP OF FLORIDA BY JULIA GARDNER PART v. TELLINACEA, SOLENACEA, MACTRACEA, MYACEA, MOLLUSCOIDEA Published June 5,1928 (Pages 185-249) UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON 1928 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington 2.5, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Introduction.__..___._-._______________________ .__ 185 Svstematic descriptions Continued. Systematic descriptions.___________________________ 189 Phylum Mollusca Continued. Phylum Mollusca__-_-___-_-________.________ 189 Class Pelecypoda Continued. Class Pelecypoda---_--__-_-_-___-__.______ 189 Order Teleodesmacea Continued. Order Teleodesmacea__________________ 189 Superfamily Myacea.__--__--______ 226 Superfamily Tellinacea-____________ 189 Family Corbulidae___-_--______ 226 Family Tellinidae___________ 189 Family Spheniopsidae._________ 236 Family Semelidae. ____________ 203 Family Saxicavidae. ___________ 237 Family Donacidae___--___--___ 211 Family Gastrochaenidae._______ 238 Family Psammobiidae.-.__.-___ 213 Phylum Molluscoidea.-.----------------------- 239 Superfamily Solenacea_____________ 216 Class Brachiopoda___---_-_-_--__-_-------_ 239 Family Solenidae. _____________ 217 Order Neotremata.____________________ 239 Superfamily Mactracea_____._-_.___ 218 Superfamily Discinacea____________ 239 Family Mactridae____-__-___-_ 219 Family Discinidae.____________ 239 Family Mesodesmatidae._______ 223 Index.___________________________________________ i ILLUSTRATIONS Page PLATES XXIX-XXXII. -

Discinid Brachiopod Life Assemblages: Fossil and Extant

Discinid brachiopod life assemblages: Fossil and extant MICHAL MERGL Clusters of discinid brachiopod shells observed in Devonian and Carboniferous strata are interpreted as original life as- semblages. The clusters consist of Gigadiscina lessardi (from Algeria), Oehlertella tarutensis (from Libya), Orbiculoidea bulla and O. nitida (both from England). Grape-like clusters of the Recent species Discinisca lamellosa and D. laevis are described and their spacing and size-frequency distribution are discussed. The possible function of clustering as protection against grazing pressure is suggested. • Key words: Discinidae, Brachiopoda, life assemblages, palaeoecology, Devonian, Carboniferous, Libya, England, Discinisca, Orbiculoidea. MERGL, M. 2010. Discinid brachiopod life assemblages: Fossil and extant. Bulletin of Geosciences 85(1), 27–38 (7 fig- ures). Czech Geological Survey, Prague. ISSN 1214-1119. Manuscript received August 14, 2009; accepted in revised form January 18, 2010; published online March 8, 2010; issued March 22, 2010. Michal Mergl, Department of Biology, University of West Bohemia, Klatovská 51, Plzeň, 30614 Czech Republic; [email protected] Fossilized natural life assemblages of rhynchonelliform habitat is common in other extant discinids. Solitary extant brachiopods have been recognized by many authors (e.g., discinids attach to various hard substrates, such as rocky sur- Hallam 1961, Johnson 1977, Alexander 1994). Peculiar faces, pebbles, mollusc shells, whale bones, and manganese grape-like clusters of extant rhynchonelliformeans have nodules (for review see Zezina 1961). been reported from New Zealand’s fjords (Richardson Several clusters of discinids, with shells in possible 1997). A communal mode of life in monospecific clusters original life position, have been observed among Devonian may also be recognized by the presence of Podichnus trace and Carboniferous fossils. -

Permophiles International Commission on Stratigraphy

Permophiles International Commission on Stratigraphy Newsletter of the Subcommission on Permian Stratigraphy Number 66 Supplement 1 ISSN 1684 – 5927 August 2018 Permophiles Issue #66 Supplement 1 8th INTERNATIONAL BRACHIOPOD CONGRESS Brachiopods in a changing planet: from the past to the future Milano 11-14 September 2018 GENERAL CHAIRS Lucia Angiolini, Università di Milano, Italy Renato Posenato, Università di Ferrara, Italy ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Chair: Gaia Crippa, Università di Milano, Italy Valentina Brandolese, Università di Ferrara, Italy Claudio Garbelli, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, China Daniela Henkel, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Germany Marco Romanin, Polish Academy of Science, Warsaw, Poland Facheng Ye, Università di Milano, Italy SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Fernando Álvarez Martínez, Universidad de Oviedo, Spain Lucia Angiolini, Università di Milano, Italy Uwe Brand, Brock University, Canada Sandra J. Carlson, University of California, Davis, United States Maggie Cusack, University of Stirling, United Kingdom Anton Eisenhauer, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Germany David A.T. Harper, Durham University, United Kingdom Lars Holmer, Uppsala University, Sweden Fernando Garcia Joral, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain Carsten Lüter, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany Alberto Pérez-Huerta, University of Alabama, United States Renato Posenato, Università di Ferrara, Italy Shuzhong Shen, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, China 1 Permophiles Issue #66 Supplement -

Brachiopods from the Eocene La Meseta Formation of Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula

BRACHIOPODS FROM THE EOCENE LA MESETA FORMATION OF SEYMOUR ISLAND, ANTARCTIC PENINSULA MARIA ALE KSA NDRA BITNER Bitner, M.A. 1996. Brachi opods from the Eoce ne La Meseta Formation of Sey mo ur Island , Antarc tic Peninsul a. In: A. Gai dz icki (ed .) Palaeon tological Result s of the Polish A ntarctic Exped itions. Part 11. - Palaeont ologia Polonica SS, 65-100. Th e rem arkabl y diverse brachi opod assemblage fro m the Eocene La Meseta Formatio n of Seymour (Murarnbio) Islan d, Antarctic Penin sul a, co nta ins nineteen ge nera and twent y four spec ies. Four genera and eight spec ies are new, i.e. Basiliola minuta sp. n., Tegu lorhynchia ampullacea sp. n., Parapli cirhvn chia gazdz icki! ge n. et sp. n.. Seymourella ow eni ge n. et sp. n., Ge n. et sp. n., Mu rravia foster! sp. n., Macandrevia cooperi sp. n., and Laquethiris curiosa gen . et sp. n. A new subfamily Sey mo urinae is prop osed for the species Seymo u rella oweni. Genera Basiliola. Hemithiris, Parapli cirhynchia. Seymourella, Murravia, Ma gel/a, Stetho thyris, Macandrevia, and Laqu ethiris are reported for the first tim e from the La Meseta Formatio n, although Hemithiris and Magella have been already noted from the Terti ary strata of adjacent Coc kburn Island. So me of the ge nera tBasiliola, Hemithiris. Notosaria, Murra via, Stethothyri s, Macand revia i described herein represent the oldest OCC UITences of the genus, thu s ex ten ding their stratig raphical ranges, which suggests that Sey mo ur Island might play an important role in the evolution of man y bruchi opod taxa from where they spread north wards before the development of the circum-A ntarc tic current in the Oligoccne time. -

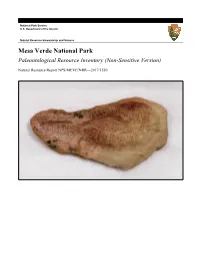

Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version)

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version) Natural Resource Report NPS/MEVE/NRR—2017/1550 ON THE COVER An undescribed chimaera (ratfish) egg capsule of the ichnogenus Chimaerotheca found in the Cliff House Sandstone of Mesa Verde National Park during the work that led to the production of this report. Photograph by: G. William M. Harrison/NPS Photo (Geoscientists-in-the-Parks Intern) Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resources Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version) Natural Resource Report NPS/MEVE/NRR—2017/1550 G. William M. Harrison,1 Justin S. Tweet,2 Vincent L. Santucci,3 and George L. San Miguel4 1National Park Service Geoscientists-in-the-Park Program 2788 Ault Park Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 45208 2National Park Service 9149 79th St. S. Cottage Grove, Minnesota 55016 3National Park Service Geologic Resources Division 1849 “C” Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 4National Park Service Mesa Verde National Park PO Box 8 Mesa Verde CO 81330 November 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Ecology of Inarticulated Brachiopods

ECOLOGY OF INARTICULATED BRACHIOPODS CHRISTIAN C. EMIG [Centre d’Océanologie de Marseille] INTRODUCTION need to be analyzed carefully at the popula- tion level before using them to interpret spe- Living inarticulated brachiopods are a cies and genera. highly diversified group. All are marine, with Assemblages with lingulides are routinely most species extending from the littoral wa- interpreted as indicating intertidal, brackish, ters to the bathyal zone. Only one species and warm conditions, but the evidence for reaches abyssal depths, and none is restricted such assumptions is mainly anecdotal. In to the intertidal zone. Among the living fact, formation of lingulide fossil beds gen- brachiopods, the lingulides, which have been erally occurred during drastic to catastrophic most extensively studied, are the only well- ecological changes. known group. Both living lingulide genera, Lingula and BEHAVIOR Glottidia, are the sole extant representatives INFAUNAL PATTERN: LINGULIDAE of a Paleozoic inarticulated group that have evolved an infaunal habit. They have a range Burrows of morphological, physiological, and behav- Lingulides live in a vertical burrow in a ioral features that have adapted them for an soft substrate. Their burrow has two parts endobiont mode of life that has remained (Fig. 407): the upper part, oval in section, remarkably constant at least since the early about two-thirds of the total length of the Paleozoic. The lingulide group shares many burrow, in which the shell moves along a features that are characteristic of this mode single plane, and the cylindrical lower part in of life including a shell shape that is oblong which only the pedicle moves (EMIG, 1981b, oval or rectangular in outline with straight, 1982). -

Middle Ordovician Phosphatic Inarticulate Brachiopods from Våstergotland and Dalarna, Sweden

Middle Ordovician phosphatic inarticulate brachiopods from Våstergotland and Dalarna, Sweden Lars E. Hollller FOSSILS AND STRATA Editor files(t he editorwill provide the necessary information on request) . Stefan Bengtson, Institute of Palaeontology, Box 558, S-751 22 Manuscript processing is designed to ensure rapid and inexpensive Uppsala, Sweden. production without compromising quality. Proofs are produced from the edited text files using desk-top-publishing techniques. Editonal and administrativeboard Galley proofs are sent to the au thors to provide opportunity to Stefan Bengtson (Uppsala) , Fredrik Bockelie (Oslo), Valdemar check the editor's changes and to revise the text if needed. Page Poulsen (Copenhagen) . proofs let the authors check the page layout, cross-references, word-breaks, etc., and to correct any remaining errors in the text. Publisher The final type will be produced on a high-resolution phototypeset Universitetsforlaget, Postboks 2959, Tøyen, N-0608 Oslo 6, Norway. ter, and both text and illustrations are printed on high-quality coated paper. Fossils and Strata is an international series of monographs and Although articles in German and French may be accepted, the memoirs in palaeontology and stratigraphy, published in coopera use of English is strongly preferred. An English abstract should tion between the Scandinavian countries. It is issued in Numbers always be provided, and non-English articles should have English with individual pagination, listed cumulatively on the back of each versions of the figure captions. Abstracts or summaries in one or cover. more additional languages may be added. Fossils and Strataforms part of the same structured publishing Many regional or systematic descriptions and revisions contain programme as the journals Lethaia and Boreas. -

A New Giant Discinoid Brachiopod from the Lower Devonian of Algeria

A new giant discinoid brachiopod from the Lower Devonian of Algeria MICHAL MERGL and DOMINIQUE MASSA Mergl, M. and Massa, D. 2005. A new giant discinoid brachiopod from the Lower Devonian of Algeria. Acta Palaeonto− logica Polonica 50 (2): 397–402. A new discinoid brachiopod Gigadiscina gen. nov., with the type species G. lessardi sp. nov., is described from the Lower Devonian (Siegenian) of the Tamesna Basin (South Ahaggar Massif, South Algeria). It is characterised by large size and convexo−planar profile of the shell, with a subcentral pedicle foramen. Micro−ornament is typically discinoid, with small cir− cular pits in radial rows on the post−larval shell surface. Related species of Malvinokaffric Realm origin from South Africa, Falkland Islands, Antarctica, South America, and Libya are reviewed, including the poorly known Discina anomala from the Lower Devonian of Germany. The giant size and convexo−planar shells of these discinoids, remarkably similar to recent lim− pets, are interpreted as adaptation to a habitat in proximity of sandy and gravel beaches in a high−energy environment. Most likely, the conical dorsal valve suppressed drag in turbulent waters, whereas fixation of shell by large, sucker−like pedicle eliminated peeling from the substrate. Key words: Brachiopoda, Discinoidea, Devonian, Algeria, Germany. Michal Mergl [[email protected]], Department of Biology, University of West Bohemia, Klatovska 51, 30614, Plzeň, Czech Republic; Dominique Massa, 6 Rue J.J. Rousseau, Suresnes, 92150 France. Introduction Genus Gigadiscina nov. Type species: Gigadiscina lessardi sp. nov.: Lower Devonian, Pragian The evolution of Silurian and Devonian discinoids is poorly (Siegenian); Tamesna Basin, Algeria.