Program Notes © 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haydn London Symphony

Portrait of Franz Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1791 WHAT MAKES IT GREAT?® HAYDN LONDON SYMPHONY 20 CONCERT PROGRAM Louis Babin Friday, February 10, 2017 Retrouvailles: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th* 7:30pm (TSO PREMIÈRE/TSO CO-COMMISSION) Rob Kapilow Rob Kapilow What Makes It Great?® conductor & host Haydn London Symphony Gary Kulesha* conductor Intermission Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 104 in D Major “London” I. Adagio – Allegro II. Andante III. Menuet: Allegro IV. Allegro spiritoso Audience Q&A with Rob Kapilow and Orchestra Please note that Louis Babin’s Retrouvailles is being recorded for online release at TSO.CA/CanadaMosaic. Tonight’s What Makes It Great?® program is all about listening. Paying attention. Noticing all the fantastic things in great music that race by at lightning speed, note by note, and measure by measure. Listening to a piece of music from the composer’s point of view—from the inside out. During the first half of the concert, we will look at selected passages from Franz Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 104 (“London”) and I will do everything in my power to get you inside the piece to Rob Kapilow hear what makes it tick and what makes it great. Then, after intermission, we will conductor perform the piece in its entirety, and you will hopefully listen to it with a whole & host new pair of ears. I am thrilled to be sharing this great music with you tonight. All you have to do is listen. 21 For a program note to Louis Babin’s Retrouvailles: Sesquie THE DETAILS for Canada’s 150th, please turn to pg. -

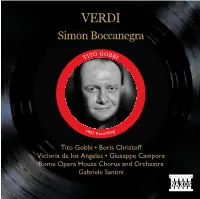

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC of BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented To

Z 2 THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC OF BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Theodore J. Albrecht, B. M. E. Denton, Texas May, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .................. iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............... ............. II. EGMONT.................... ......... 0 0 05 Historical Background Egmont: Synopsis Egmont: the Music III. KONIG STEPHAN, DIE RUINEN VON ATHEN, DIE WEIHE DES HAUSES................. .......... 39 Historical Background K*niq Stephan: Synopsis K'nig Stephan: the Music Die Ruinen von Athen: Synopsis Die Ruinen von Athen: the Music Die Weihe des Hauses: the Play and the Music IV. THE LATER PLAYS......................-.-...121 Tarpe.ja: Historical Background Tarpeja: the Music Die gute Nachricht: Historical Background Die gute Nachricht: the Music Leonore Prohaska: Historical Background Leonore Prohaska: the Music Die Ehrenpforten: Historical Background Die Ehrenpforten: the Music Wilhelm Tell: Historical Background Wilhelm Tell: the Music V. CONCLUSION,...................... .......... 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY.....................................-..145 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Egmont, Overture, bars 28-32 . , . 17 2. Egmont, Overture, bars 82-85 . , . 17 3. Overture, bars 295-298 , . , . 18 4. Number 1, bars 1-6 . 19 5. Elgmpnt, Number 1, bars 16-18 . 19 Eqm 20 6. EEqgmont, gmont, Number 1, bars 30-37 . Egmont, 7. Number 1, bars 87-91 . 20 Egmont,Eqm 8. Number 2, bars 1-4 . 21 Egmon t, 9. Number 2, bars 9-12. 22 Egmont,, 10. Number 2, bars 27-29 . 22 23 11. Eqmont, Number 2, bar 32 . Egmont, 12. Number 2, bars 71-75 . 23 Egmont,, 13. -

PDF 139.88KB Rps Abo Salomon Prize 2013

Press Release For release: Friday 10 January 2014 ‘Unsung heroine’ of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, violinist Catherine Arlidge, a “true advocate of the modern orchestral musician” awarded prestigious RPS/ABO Salomon Prize for orchestral musicians. Catherine Arlidge of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra becomes the first violinist – and only the third ever recipient – of the RPS/ABO Salomon Prize, a prestigious award celebrating the outstanding contribution of orchestral players to the UK’s musical life. The UK boasts many of the world’s finest orchestras, many of which have trophy cabinets bursting with awards in testimony to their brilliance on the concert platform and in the recording studio. Yet, the contribution of individual musicians within an orchestra often goes unnoticed. The Salomon Prize* was created by the Royal Philharmonic Society and Association of British Orchestras in 2011 to celebrate the ‘unsung heroes’ of orchestral life; the orchestral players that make our orchestras great. The award is named after Johann Peter Salomon, violinist and founding member of the Philharmonic Society in 1813. Each year, players in all orchestras across the UK are asked to nominate a colleague who has been ‘an inspiration to their fellow players, fostered greater spirit of teamwork and shown commitment and dedication above and beyond the call of duty’. Catherine Arlidge, Sub Principal of the second violins, who has played with the CBSO for over 20 years, was nominated by her fellow musicians and the CBSO’s management for her creativity, energy and “great skill for motivating and inspiring colleagues and for engaging with her audience”. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Quartet Dimensions

concert program ii: Quartet Dimensions JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)! July 21 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Sunday, July 21, 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts Fugue in E-flat Major, BWV 876, and Fugue in d minor, BWV 877, from at Menlo-Atherton Das wohltemperierte Klavier; arr. String Quartets nos. 7 and 8, K. 405 JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) PROGRAM OVERVIEW String Quartet in d minor, op. 76, no. 2, Quinten (1796) The string quartet medium, arguably the spinal column of the Allegro chamber music literature, did not exist in Bach’s lifetime. Yet Andante o più tosto allegretto Minuetto: Allegro ma non troppo even here, Bach’s legacy is inescapable. The fugues of his semi- Finale: Vivace assai nal The Well-Tempered Clavier inspired no less a genius than Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola; Mozart, who arranged a set of them for string quartet. The influ- Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello ence of Bach’s architectural mastery permeates the ingenious DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quinten Quartet of Joseph Haydn, the father of the modern Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) string quartet, and even Dmitry Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet, Prelude composed nearly two hundred years after Bach’s death. The Fugue Scherzo centerpiece of Beethoven’s Opus 132—the Heiliger Dankgesang Intermezzo CONCERT PROGRAMSCONCERT eines Genesenen an die Gottheit (“A Convalescent’s Holy Song Finale PROGRAMSCONCERT of Thanksgiving to the Divinity”)—recalls another Bachian signa- Gilbert Kalish, piano; Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; ture: the Baroque master’s sacred chorales. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season April 23, 2017 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR TILL FELLNER, PIANO FRANZ SCHUBERT Selections from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 I. Overture II. Ballet Music No. 2 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto No. 3 for Piano and Orchestra in C minor, Opus 37 I. Allegro con brio II. Largo III. Rondo: Allegro Mr. Fellner Intermission WOLFGANG AMADEUS Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, “Jupiter” MOZART I. Allegro vivace II. Andante cantabile III. Allegretto IV. Molto allegro PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA FRANZ SCHUBERT Overture and Ballet Music No. 2 from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 (1820 and 1823) Franz Schubert was born in Vienna on January 31, 1797, and died there on November 19, 1828. He composed the music for Rosamunde during the years 1820 and 1823. The ballet was premiered in Vienna on December 20, 1823 at the Theater-an-der-Wein, with the composer conducting. The Incidental Music to Rosamunde was first performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony on November 9, 1906, conducted by Emil Paur at Carnegie Music Hall. Most recently, Lorin Maazel conducted the Overture to Rosamunde on March 14, 1986. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. Performance tine: approximately 17 minutes Schubert wrote more for the stage than is commonly realized. His output contains over a dozen works for the theater, including eight complete operas and operettas. Every one flopped. Still, he doggedly followed each new theatrical opportunity that came his way. -

Cooper Plays Mozart April 2017

Imogen Cooper Plays Mozart Jane Glover, conductor Imogen Cooper, piano Sunday, April 23, 2017, 7:30 PM North Shore Center for the Performing Arts, Skokie Monday, April 24, 2017, 7:30 PM Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Chicago Ballet Music from Idomeneo, K. 367 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Chaconne—Larghetto—La Chaconne, qui reprend Pas seul: Largo—Allegretto—più Allegro Piano Concerto No. 25 in C Major, K. 503 Mozart Allegro maestoso Andante Allegretto INTERMISSION Symphony No. 101 in D Major (Clock) Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Adagio—Presto Andante Menuet: Allegretto—Trio Finale: Vivace These performances are generously underwritten by the Elizabeth F. Cheney Foundation. Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra Jane Glover, Music Director Violin 1 Flute Gina DiBello, Mary Stolper, principal concertmaster Alyce Johnson Kevin Case, assistant concertmaster Oboe Kathleen Brauer, Anne Bach, principal assistant Erica Burtner Anderson concertmaster Teresa Fream Clarinet Michael Shelton Steve Cohen, principal Martin Davids Daniel Won Violin 2 Bassoon Sharon Polifrone, William Buchman, principal principal Ann Palen Lewis Kirk Rika Seko Paul Vanderwerf Horn François Henkins Oto Carrillo, principal Samuel Hamzem Viola Elizabeth Hagen, Trumpet principal Barbara Butler, principal Terri Van Valkinburgh Channing Philbrick Claudia Lasareff- Mironoff Timpani Benton Wedge Douglas Waddell Cello Barbara Haffner, principal Judy Stone Matt Agnew Bass Collins Trier, principal Andrew Anderson Biographies Acclaimed British conductor Jane Glover has been Music of the Baroque’s music director since 2002. She made her professional debut at the Wexford Festival in 1975, conducting her own edition of Cavalli’s L’Eritrea. She joined Glyndebourne in 1979 and was music director of Glyndebourne Touring Opera from 1981 until 1985. -

SILVANA SINTOW Roberto Scandiuzzi Bass

Silvana Sintow Classicalia International Promotions & Management Schleibingerstrasse 8 - 81669 München - Germany • Tel: + 49-89- 44 21 89 00 e-mail: [email protected] • www.classicalia-international.com • Fax: + 49-89- 44 21 89 03 Roberto Scandiuzzi Bass Roberto Scandiuzzi studied with Anna Maria Bicciato in his native Treviso and made his debut at La Scala in Milan in 1982 with „Le nozze di Figaro“ under the direction of Riccardo Muti. Shortly thereafter he achieved his first great international success as Fiesco in „Simon Boccanegra“ at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden conducted by Georg Solti. Today he is one of the most renowned singers of the operatic world and enthuses the audience with his vocal beauty, his round and noble timbre and his electrifying stage presence. He is often compared with famous basses such as Ezio Pinza and Cesare Siepi, by whom he was strongly influenced. Roberto Scandiuzzi frequently appears at the most prestigious opera houses worldwide: at the Metropolitan Opera, the Opéra-Bastille in Paris, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, State Operas of Vienna and Munich, the San Francisco Opera and Zürich Opera House as well as with the leading symphonic orchestras such as the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Orchestras of Chicago, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Boston and Los Angeles, the Orchestra Filarmonica della Scala, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Orchestre National de Paris and Orchestre National de France, the Symphony Orchestra of Bavarian Radio and the Munich Philharmonic. The vast list of conductors he worked with includes celebrities such as Claudio Abbado, Sir Colin Davis, Valéry Gergiev, Christoph Eschenbach, Gian Luigi Gelmetti, James Levine, Fabio Luisi, Lorin Maazel, Zubin Mehta, Riccardo Muti, Seiji Ozawa, Myung Whun Chung, Giuseppe Sinopoli, Georges Prêtre, Marcello Viotti and Wolfgang Sawallisch. -

Ernani Giuseppe Verdi Operas and Revision

Ernani Giuseppe Verdi Operas and Revision • Oberto, conte di San Bonifacio • First performance: Milan, Scala, 17 Nov 1839. • Un giorno di regio (Il Finto Stanislao) • First performance: Milan, Scala, 5 Sept 1840; alternative title used 1845 • Nabuccodonosor (Nabucco) • first performance: Milan, Scala, 9 March 1842 • Lombardi alla prima crociata • First performed: Milan, Scala, 11 Feb 1843 • Ernani • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 9 March 1844 • I due Foscari • First performance: Rome, Argentina, 3 Nov 1844 • Giovanna d’Arco • First performance: Milan, Scala, 15 Feb 1845 • Alzira • First performance: Naples, S Carlo, 12 Aug 1845 • Macbeth • First performance: Florence, Pergola, 14 March 1847 • I masnadieri • First performance: London, Her Majesty’s, 22 July 1847 • Jérusalem • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 26 Nov 1847 • Il Corsaro • First performance: Trieste, Grande, 25 October 1848 • La battaglia di Legnano • First performance: Rome, Argentina, 27 Jan 1849 • Luisa Miller • First performance: Naples, S Carlo, 8 Dec 1848 • Stiffelio • First performance: Trieste, Grnade, 16 Nov 1850; autograph used for Aroldo, 1857 • Rigoletto • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 11 March 1851 • Il trovatore • First performance: Rome, Apollo, 19 Jan 1853 • La Traviata • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 6 March 1853 • Les vêpres siciliennes • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 13 June 1855 • Simon Boccanegra • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 12 March 1857, rev. version Milan, Scala, 24 March 1881 • Aroldo • First performance: Rimini, Nuovo, 16 Aug 1857 • Un ballo in maschera • First performance: Rome, Apollo, 17 Feb 1859 • La forza del destino • First performance: St Petersburg, Imperial, 10 Nov 1862, rev. version Milan, Scala, 27 Feb 1869 • Don Carlos • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 11 March 1867, rev. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program 4, Christopher Taylor

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL Part Four: Christopher Taylor, Piano December 17, 2020 ~ 8:00 pm The Library of Congress Virtual Event We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. Conversation with the Artist Join us online at https://loc.gov/concerts/christopher-taylor.html for a conversation with the artist, and find additional resources related to the concert, available starting at 10am on Thursday, December 17. Facebook Chat Want more? Join other concert goers and Music Division curators after the concert for a chat that may include the artists, depending on availability. You can access this during the premiere and for a few minutes after by going to facebook.com/pg/libraryofcongressperformingarts/videos How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc 3) Watch the premiere of the concert on Facebook: facebook.com/libraryofcongressperformingarts/videos Videos may not be available on all three platforms, and some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. The Library of Congress Virtual Event December 17, 2020 — 8:00 pm Friends of Music (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL Part Four Page 4) Christopher Taylor, piano 1 (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL Welcome to the (Re)Hearing Beethoven Festival, a series of unique concerts pre- sented virtually by Concerts from the Library of Congress. -

VERDI Also Available Simon Boccanegra

8.110119-20 bk Boccanegra_EU 12/12/08 1:42 PM Page 12 VERDI Also Available Simon Boccanegra O GOB TIT BI 8.111334-35 8.111240-41 1 g 957 Recordin Tito Gobbi • Boris Christoff Victoria de los Angeles • Giuseppe Campora 8.111284-85 8.111332-33 Rome Opera House Chorus and Orchestra Gabriele Santini 8.110119-20 12 8.110119-20 bk Boccanegra_EU 12/12/08 1:42 PM Page 2 Great Opera Recordings pleads for death and Amelia is moved by his great love, whom he had thought dead. Boccanegra forgives him, seeking to heal old enmities. £ He returns, as a ghost, to avenge outrage. The lights & Shouts are heard outside and calls to arms, the start of begin to go out in the piazza outside. Boccanegra, Giuseppe the rebellion against the Doge, who bids Gabriele join his however, is relieved at Fiesco’s appearance and can friends. The latter demurs, now loyal to Boccanegra and announce peace between them. He tells him that his own VERDI rewarded with the hand of Amelia. daughter and Fiesco’s grand-daughter is Amelia Grimaldi. (1813 - 1901) Act 3 ¢ Fiesco weeps at the revelation. He hears in Boccanegra’s words the voice of Heaven. Boccanegra * From the Doge’s palace Genoa can be seen, seeks to embrace him, the father of his beloved Maria. Simon Boccanegra illuminated as for a festival. The shouts of the crowd are Fiesco tells Boccanegra of the poison. The latter is Opera in a Prologue and Three Acts heard, praising the Doge. growing weaker and collapses onto a seat, as Amelia, Text by Franceso Maria Piave as modified by Arrigo Boito ( A captain of the bowmen gives Fiesco back his sword Gabriele, ladies, gentlemen, senators and pages with and tells him he is free.