LICADHO Human Rights Defenders Report 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collective Land Registration of Indigenous Communities in Ratanakiri Province

Briefing Note Senate Region 8 Collective Land Registration of Indigenous Communities in Ratanakiri province Researcher in charge: Mr. KHAM Vanda Assisted by: Mr. NUN Assachan Ms. CHEA Malika Ms. WIN Moh Moh Htay April, 2016 Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia Notice of Disclaimer The Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia (PIC) is an independent parliamentary support institution for the Cambodian Parliament which, upon request from parliamentarians and parliamentary commissions, offers a wide range of services. These include capacity development in the form of training, workshops, seminars and internships, as well as support for outreach activities. Parliamentary research has been a particular focus and PIC has placed an emphasis on developing the associated skills of parliamentary staff while producing the research reports needed to guide Parliamentarians in pursuing their legislation role. PIC research reports provide information about subjects that are relevant to parliamentary and constituency work including key emerging issues, legislation and major public policy topics. They do not, however, purport to represent or reflect the views of the Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia, the Parliament of Cambodia, or of any of its members. The contents of these reports, current at the date of publication, are for reference purposes only. They are not designed to provide legal or policy advice, and do not necessarily deal with every important topic or aspect of the issues they consider. The contents of this research report are covered by applicable Cambodian laws and international copyright agreements. Permission to reproduce in whole or in part or otherwise use the content of this research may be sought from the appropriate source. -

00836420 I:J~I!, A

00836420 DI07/2.1 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Transcription of interview Interviewed by: Interview granted by: Mr OEUN Tan (UUB fOB) i:J~i!, 9 October 2008 TRANSLATIONITRADUCTION iy ill [1 (Date):.~.~:~.~~~?~.~.~:.~~.:.~~. (Partial transcription of the audio file Dl07/2R) CMS/CFO: ......~.~.~.~.~.~~!:I.~~.~.!'! .... Questions (Q) - Answers (A): [00:03:00] Q: [ ... ] made a living, gained wealth and got together with children and grandchildren. Uncle, dare you swear: "I state only the truth" ? A: I state only the truth, meaning what I am sure about, I speak about it. Q: Yes, yes. Thanks a lot. A: As for what I am not sure about, I will not speak about it. Q: So, Uncle, you will swear following this! A: Yes, yes. Q: Thanks. And for another thing, I would also like to tell of your rights. As a witness, Uncle, you have the right not to respond to any questions you think, when you respond to them, will implicate you. But if you want to respond, you can do so. If you do not, it is alright. As for any questions you think, when you respond to them, may implicate you, you may not answer them - that is also possible. This is your right recognized by our law. So, Uncle, thank you. I begin to ask you officially. Uncle, your name is OEUN Tan. You do not have any alias? A: No, I don't have. Q: And how about your wife-what is her name? [00:03:47] A: SOKH Oeun (tll2 Uf)~) Q: SOKH Oeun. And how old are you, Uncle, as of this year? A: Sixty five. -

A Second Complaint

Osvaldo Gratacós Vice President Office of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman International Finance Corporation 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Tel: + 1 202-458-1973 Fax: +1 202-522-7400 e-mail: [email protected] March 12, 2019 Dear Vice President Gratacós, Re: Complaint concerning IFC investments in Tien Phong Commercial Joint Stock Bank (TPBank) and Vietnam Prosperity Joint Stock Commercial Bank (VPBank) 1. Inclusive Development International (IDI), Equitable Cambodia (EC), Highlanders Association (HA) and Indigenous Rights Active Members (IRAM) are submitting this complaint to the Office of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman on behalf of communities adversely affected by a sub-project of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) through financial intermediary clients Tien Phong Commercial Joint Stock Bank (TPBank) and Vietnam Prosperity Joint Stock Commercial Bank (VPBank). Authorizations of representation accompany this letter of complaint. 2. The complainants are 12 communities in Ratanakiri Province, Cambodia who have suffered serious harm as a result of the activities of Hoang Anh Gia Lai (HAGL), a Vietnamese company operating in Cambodia through several wholly-owned subsidiaries. 3. The villages are located in the districts of Andong Meas and O’Chum. The villages consist mainly of Jarai, Kachok, Tampuon, and Kreung peoples, who identify as and are in many cases legally recognized by the government as Indigenous Communities. They are traditionally animist, and their culture, livelihoods and identities are intimately tied to the land, forests and other natural resources of the region. The communities practice shifting cultivation and rely heavily on forest resources for their livelihoods. The name, location and other characteristics of each village are set out in Annex 1. -

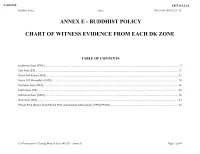

Buddhist Policy Chart of Witness Evidence from Each

ERN>01462446</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC ANNEX E BUDDHIST POLICY CHART OF WITNESS EVIDENCE FROM EACH DK ZONE TABLE OF CONTENTS Southwest Zone [SWZ] 2 East Zone [EZ] 12 Sector 505 Kratie [505S] 21 Sector 105 Mondulkiri [105S] 24 Northeast Zone [NEZ] 26 North Zone [NZ] 28 Northwest Zone [NWZ] 36 West Zone [WZ] 43 Phnom Penh Special Zone Phnom Penh Autonomous Municipality [PPSZ PPAM] 45 ’ Co Prosecutors Closing Brief in Case 002 02 Annex E Page 1 of 49 ERN>01462447</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC SOUTHWEST ZONE [SWZ] Southwest Zone No Name Quote Source Sector 25 Koh Thom District Chheu Khmau Pagoda “But as in the case of my family El 170 1 Pin Pin because we were — we had a lot of family members then we were asked to live in a monk Yathay T 7 Feb 1 ” Yathay residence which was pretty large in that pagoda 2013 10 59 34 11 01 21 Sector 25 Kien Svay District Kandal Province “In the Pol Pot s time there were no sermon El 463 1 Sou preached by monks and there were no wedding procession We were given with the black Sotheavy T 24 Sou ” 2 clothing black rubber sandals and scarves and we were forced Aug 2016 Sotheavy 13 43 45 13 44 35 Sector 25 Koh Thom District Preaek Ph ’av Pagoda “I reached Preaek Ph av and I saw a lot El 197 1 Sou of dead bodies including the corpses of the monks I spent overnight with these corpses A lot Sotheavy T 27 of people were sick Some got wounded they cried in pain I was terrified ”—“I was too May 2013 scared to continue walking when seeing these -

Pdf IWGIA Book Land Alienation 2006 EN

Land Alienation in Indigenous Minority Communities - Ratanakiri Province, Cambodia Readers of this report are also directed toward the enclosed video documentary made on this topic in October 2005: “CRISIS – Indigenous Land Crisis in Ratanakiri”. Also relevant is the Report “Workshop to Seek Strategies to Prevent Indigenous Land Alienation” published by NGO Forum in collaboration with CARE Cambodia, 28-20 March 2005. - Final Draft- August 2006 Land Alienation in Indigenous Minority Communities - Ratanakiri Province, Cambodia Table of Contents Contents............................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 4 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 5 Executive Summary – November 2004................................................................................. 6 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology...................................................................................................................... 10 The Legal Situation.............................................................................................................. 11 The Situation in January 2006 ............................................................................................ -

KINGDOM of CAMBODIA Royal Goverment of Cambodia 4Th, 5Th

Translation KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA NATION RELIGION KING 7 Royal Goverment of Cambodia th th th 4 , 5 and 6 National Report On The implementation of Convention on the Rights of the Child in Cambodia 2008-2018 Prepaired by: Cambodia National Council for Children Contents Page I. Introduction --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 A. Country Profile ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1 1. Demographic Characteristics ----------------------------------------------------------------- 1 B. Economic------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 C. Process of the report ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1 II. General Measure of Implementation --------------------------------------------------------------- 2 A. Legal Framework --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 B. Implementing Mechanism and Coordination ------------------------------------------------- 2 C. Allocation of Resource --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 D. National Action Plan ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 E. International Assistance and Development Aid ---------------------------------------------- 5 F. Independent Monitoring Institution ------------------------------------------------------------ 6 G. Dissemination and Awareness Raising -------------------------------------------------------- -

Cambodia Municipality and Province Investment Information

Cambodia Municipality and Province Investment Information 2013 Council for the Development of Cambodia MAP OF CAMBODIA Note: While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the information in this publication is accurate, Japan International Cooperation Agency does not accept any legal responsibility for the fortuitous loss or damages or consequences caused by any error in description of this publication, or accompanying with the distribution, contents or use of this publication. All rights are reserved to Japan International Cooperation Agency. The material in this publication is copyrighted. CONTENTS MAP OF CAMBODIA CONTENTS 1. Banteay Meanchey Province ......................................................................................................... 1 2. Battambang Province .................................................................................................................... 7 3. Kampong Cham Province ........................................................................................................... 13 4. Kampong Chhnang Province ..................................................................................................... 19 5. Kampong Speu Province ............................................................................................................. 25 6. Kampong Thom Province ........................................................................................................... 31 7. Kampot Province ........................................................................................................................ -

Along the Road 76 Old Bridge Data : N/A New Bridge Data : Steel Bridge Observation Location : X = .711220 , Y =

ANNEX VIII-2 FIELD CHECK IN RATTANAK KIRI PROVINCE Field Check in Rattanak Kiri Province Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. Cover Rattanak Kiri area ( Map sheets : 6335, 6435, 6535, 6336, 6436, 6536, 6337, 6437 ) ................................................................................................................................. 1 3. Metheology : For the field check conducted two group :........................................... 2 4. Located Resources............................................................................................................ 3 5. Data correction : For the whole Rattanak Kiri province :........................................... 3 6. Data Comparition : .......................................................................................................... 4 6.1. V.I. Along the road 78 From Stueng Srae Pork bridge to Vietnam border and connected :.........4 6.1.1. From Ban Lung to Vietnam border:...................................................................... 4 6.1.2. Ban Lung to Stueng Srae Pok bridge .................................................................. 12 7. Road No. 76 From Ou Cheng to Lumphat disrict :.................................................. 13 8. Along the road 78a From banlong to Veun Sai disrict :........................................... 17 9. Along the road 76a From Banlung to Ta Veng disrict : ............................................ -

Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) CAMBODIA Grant-Support for Civil Society Organizations Project Brief No

Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) CAMBODIA Grant-support for civil society organizations Project brief no. 1 February 2017 Tuol Ta Aek Rotanak Battambang province Strengthening Commune Capacities and Institutions for Mainstreaming Climate Resilience into Commune Development Plans Commune Profile Traditional coping strategies: built waterways to direct excess water away to lower lands in the Commune: Sangkat Tuol Ta Aek and Rotanak, communities Battambang Municipality Targeted stakeholders: women, elderly and Population: 32,845 children Livelihood activities: agriculture (rice and crop farming), non-farm activities such as construction Outcome workers, guards, cleaners, and drivers Improved urban infrastructure and enhanced capacity of local authorities and communities in urban areas to integrate CCA Vulnerability Profile and DRR actions into commune investment plans/commune Climate hazards: increased intensity and development plans frequency of flooding from localized rainfall and river overflowing Outputs Impacts: decline in rice and crop yield; damage to Design of a wastewater master plan, including drainage infrastructure; inaccessibility of markets, drainage systems, developed and endorsed schools, and other services in times of floods; outbreak of vector borne diseases such as malaria Coordination among target communities and local and dengue; poor sanitation as flooding often authorities enhanced damages pit latrines Climate change knowledge products on drainage Key issues: limited capacity of drainage network to rehabilitation -

International Rivers Completion Report, August 2013 O

OM 4.5.4 (Rev) CEPF FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT Organization Legal Name: Save Cambodia’s Wildlife Community Empowerment for Biodiversity Conservation Project Title: along Seasan and Srepok Rivers of Mekong Basin Date of Report: August 30, 2013 Mr. Mean Chamreoun, Project Officer Report Author and Contact Email: [email protected] Information Mobile: 012 23 10 74 Acronym 3SPN 3S Rivers Protection Network CC Commune Councils CDP Commune Development Plan CEPF Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund CIP Commune Investment Program/Plan DIW District Integration Workshop NRM Natural Resource Management RCC Rivers Coalition in Cambodia SCW Save Cambodia’s Wildlife CEPF Region: Indo-Burma Strategic Direction: 3: engage key actors in reconciling biodiversity conservation and development objectives, with a particular emphasis on the Mekong River and its tributaries. Grant Amount: $108,330 Project Dates: 1 July, 2010 to 30 June, 2013 Implementation Partners for this Project (please explain the level of involvement for each partner): SCW has coordinated the meetings with 3SPN, Fishery Administration and Lumphath Wildlife Sanctuary to develop quarterly action plan of 3S community network and trainings on participatory approach of community biodiversity conservation such as natural resource management, Fishery Law, commune investment program (CIP) and good governance and advocacy. Linked affected communities to RCC for Peace Walk in Kampongcham Province to against the dam project in Mekong mainstream. International Rivers Completion Report, August 2013 Page 1 Conservation Impacts Please explain/describe how your project has contributed to the implementation of the CEPF ecosystem profile. As a conservation organization, SCW has implemented its project in the area along the main tributaries of the Mekong rivers, where is called the Sesan and Srepok rivers. -

Electricity of Vietnam Power Engineering Consulting Company No

www.sweco.no Electricity of Vietnam Power Engineering Consulting Company no. 1 FINAL REPORT Environmental Impact Assessment on the Cambodian part of the Se San River due to Hydropower Development in Vietnam December 2006 SWECO Grøner in association with Norwegian Institute for Water Research, ENVIRO-DEV, and ENS Consult Environmental Impact Assessment on the Cambodian part of the Se San River December 2006 due to hydropower development in Vietnam Final Report SWECO Grøner in association with Final Report 2/187 NIVA, ENVIRO-DEV, and ENS Consult Environmental Impact Assessment on the Cambodian part of the Se San River December 2006 due to hydropower development in Vietnam Final Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................7 1. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY.............................................................................18 1.1 .....BACKGROUND .........................................................................................................................18 1.2 .....OBJECTIVES OF THE PROJECT ..................................................................................................19 1.3 .....BASELINE DESCRIPTION ..........................................................................................................20 1.4 .....DATA, METHODS AND LIMITATIONS .......................................................................................20 -

Sociolinguistic Survey of Jarai in Ratanakiri, Cambodia

Sociolinguistic survey of Jarai in Ratanakiri, Cambodia Eric Pawley Mee-Sun Pawley International Cooperation Cambodia November 2010 2007-02 Jarai Survey Report v1.2.odt Printed 9. Oct. 2013 i Abstract Eric Pawley [Phnom Penh, Cambodia] This paper presents the report of a sociolinguistic survey of the Jarai variety spoken in Ratanakiri province, Cambodia. Jarai is one of the major “Montagnard” groups of the Vietnamese southern highlands. While Jarai numbers in Cambodia are much smaller, it is still one of the largest highland minority groups. This paper investigates the dialects used among the Jarai speakers in Ratanakiri province, their abilities in Khmer, and their attitudes towards language development. The data indicates that a minority of Jarai can speak some Khmer, but very few can read or write in either Khmer or Jarai. Nearly everyone interviewed expressed interest in learning to read and write Jarai. While many prefer the Roman script used by Jarai in Vietnam over the creation of a new Khmer- based script, most said that they would still be interested in learning a new script if it were made. There are only minor dialect differences between Jarai in Cambodia, but much greater differences with some varieties of Jarai spoken in Vietnam. ii Table of Contents 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Geography.................................................................................................................................1