Introduction John Madden Chairman: Bartons’ History Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gagingwell Oxfordshire

Gagingwell Oxfordshire Gagingwell, Oxfordshire A rarely available four bedroom stone barn conversion that has a wealth of character and fine countryside views. The property is centrally located with excellent access to the road network. Soho Farmhouse only minutes away. Master Bedroom, En-Suite Bathroom, Three Further Bedrooms, Bathroom, Sitting Room, Dining Hall, Snug, Kitchen/Breakfast Room, Utility Room, Cloakroom, Driveway, Additional Parking Space, Front and Rear Gardens. Gagingwell is a hamlet well located in rolling countryside on the edge of the Cotswolds, between Oxford and Chipping Norton. We believe that the majority of Gagingwell's few houses are late 17th or 18th century stone buildings with roofs of Stonesfield Slate or, in one case, thatch. In nearby Great Tew is an Ofsted Outstanding Primary School, with further excellent schools nearby, including Tudor Hall near Banbury, Bloxham School and the Oxford schools including Dragon School, Summer Fields, Magdalen College School and Headington School. Comprehensive shopping facilities are available in the market towns of Chipping Norton, Oxford and Banbury. Tiled porch to hard wood front door to: Entrance Hall: Stone floor. Cloakroom: Comprising white suite of low level WC, hand wash basin set on a pine plinth with cupboards below, built in airing cupboard, wooden floor. Utility Room: Stone floor, plumbing for washing machine, exposed stone wall. Dining Hall: Wooden floor, balustrade staircase to first floor level with under stairs cupboard, exposed stone wall, exposed beam. Sitting Room: Attractive open stone fireplace with tiled hearth, exposed stone walls, double glazed window to front aspect, double glazed French doors to courtyard, exposed beam. -

Archaeological Work in Oxford, 2012

Oxoniensia 78 txt 4+index_Oxoniensia 17/11/2013 12:05 Page 213 ROMANO-BRITISH VILLA AT COMBE 213 NOTES Archaeological Work in Oxford, 2012 In 2012 the Heritage and Specialist Services Team completed the Oxford Archaeological Plan (OAP). The resulting resource assessment, research agenda and characterisation reports are available on the council website, along with a six-year Archaeological Action Plan for the city. The year also saw a number of substantial city centre projects resulting from the expansion of college facilities, and some notable new information resulting from small-scale commercial and domestic development. Provisional summaries for selected sites are provided below. SELECTED PROJECTS 19 St Andrew’s Lane, Headington In January JMHS carried out an archaeological evaluation prior to the construction of a small extension at 19 St Andrew’s Lane. The evaluation recorded a post-medieval well and a series of cess pits filled with dump deposits containing animal bone, late-medieval and early post- medieval pottery and brick. At least six post holes from an unidentified structure possibly post- dating the pits were recorded. Nos. 6–7 High Street (Jack Wills, formerly Ryman’s Stationers) In February three test pits were excavated in the basement of Nos. 6–7 High Street by OA. A number of medieval pits containing domestic and butchery waste were recorded, along with a stone drain or wall foundation. The backfill of one feature contained a fired clay annular discoidal loom weight of likely early to middle Anglo-Saxon date (c.400–850). In June a lift pit was excavated in the basement revealing in section the edge of a possible wood-lined pit, potentially a ‘cellar pit’. -

Oxfordshire. Chipping Nor Ton

DIRI::CTOR Y. J OXFORDSHIRE. CHIPPING NOR TON. 79 w the memory of Col. Henry Dawkins M.P. (d. r864), Wall Letter Box cleared at 11.25 a.m. & 7.40 p.m. and Emma, his wife, by their four children. The rents , week days only of the poor's allotment of so acres, awarded in 1770, are devoted to the purchase of clothes, linen, bedding, Elementary School (mixed), erected & opened 9 Sept. fuel, tools, medical or other aid in sickness, food or 1901 a.t a. cost of £ r,ooo, for 6o children ; average other articles in kind, and other charitable purposes; attendance, so; Mrs. Jackson, mistress; Miss Edith Wright's charity of £3 I2S. is for bread, and Miss Daw- Insall, assistant mistress kins' charity is given in money; both being disbursed by the vicar and churchwardens of Chipping Norton. .A.t Cold Norron was once an Augustinian priory, founded Over Norton House, the property of William G. Dawkina by William Fitzalan in the reign of Henry II. and esq. and now the residence of Capt. Denis St. George dedicated to 1818. Mary the Virgin, John the Daly, is a mansion in the Tudor style, rebuilt in I879, Evangelist and S. Giles. In the reign of Henry VII. and st'anding in a well-wooded park of about go acres. it was escheated to the Crown, and subsequently pur William G. Dawkins esq. is lord of the manor. The chased by William Sirlith, bishop of Lincoln (I496- area is 2,344 acres; rateable value, £2,oo6; the popula 1514), by-whom it was given to Brasenose College, Ox tion in 1901 was 3so. -

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford Mondays to Saturdays notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F Witney Market Square stop C 06.14 06.45 07.45 - 09.10 10.10 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.20 - Madley Park Co-op 06.21 06.52 07.52 - - North Leigh Masons Arms 06.27 06.58 07.58 - 09.18 10.18 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.28 17.30 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 06.35 07.06 08.07 07.52 09.27 10.27 11.32 12.32 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.37 17.40 Long Hanborough New Road 06.40 07.11 08.11 07.57 09.31 10.31 11.36 12.36 13.36 14.36 15.36 16.41 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 06.49 07.21 08.20 09.40 10.40 11.45 12.45 13.45 14.45 15.45 16.50 Eynsham Church 06.53 07.26 08.24 08.11 09.44 10.44 11.49 12.49 13.49 14.49 15.49 16.54 17.49 Botley Elms Parade 07.06 07.42 08.33 08.27 09.53 10.53 11.58 12.58 13.58 14.58 15.58 17.03 18.00 Oxford Castle Street 07.21 08.05 08.47 08.55 10.07 11.07 12.12 13.12 13.12 15.12 16.12 17.17 18.13 notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F S Oxford Castle Street E2 07.25 08.10 09.10 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.35 16.35 17.35 17.50 Botley Elms Parade 07.34 08.20 09.20 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 15.25 16.45 16.50 17.50 18.00 Eynsham Church 07.43 08.30 09.30 10.35 11.35 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.55 17.00 18.02 18.10 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 09.34 10.39 11.39 12.39 13.39 14.39 15.39 16.59 17.04 18.06 18.14 Long Hanborough New Road 09.42 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 17.07 17.12 18.14 18.22 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 07.51 08.38 09.46 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 17.11 17.16 18.18 18.26 North Leigh Masons Arms - 08.45 09.55 11.00 12.00 13.00 -

WIN a ONE NIGHT STAY at the OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always More to Discover

WIN A ONE NIGHT STAY AT THE OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always more to discover Tours & Exhibitions | Events | Afternoon Tea Birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill | World Heritage Site BUY ONE DAY, GET 12 MONTHS FREE ATerms precious and conditions apply.time, every time. Britain’sA precious time,Greatest every time.Palace. Britain’s Greatest Palace. www.blenheimpalace.com Contents 4 Oxford by the Locals Get an insight into Oxford from its locals. 8 72 Hours in the Cotswolds The perfect destination for a long weekend away. 12 The Oxfordshire Thames Path Take a walk along the Thames Path and enjoy the most striking riverside scenery in the county. 16 Film & TV Links Find out which famous films and television shows were filmed around the county. 19 Literary Links From Alice in Wonderland to Lord of the Rings, browse literary offerings and connections that Oxfordshire has created. 20 Cherwell the Impressive North See what North Oxfordshire has to offer visitors. 23 Traditions Time your visit to the county to experience at least one of these traditions! 24 Transport Train, coach, bus and airport information. 27 Food and Drink Our top picks of eateries in the county. 29 Shopping Shopping hotspots from around the county. 30 Family Fun Farm parks & wildlife, museums and family tours. 34 Country Houses and Gardens Explore the stories behind the people from country houses and gardens in Oxfordshire. 38 What’s On See what’s on in the county for 2017. 41 Accommodation, Tours Broughton Castle and Attraction Listings Welcome to Oxfordshire Connect with Experience Oxfordshire From the ancient University of Oxford to the rolling hills of the Cotswolds, there is so much rich history and culture for you to explore. -

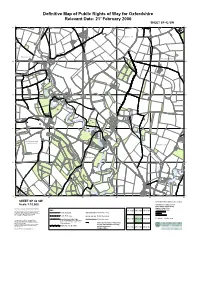

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 42 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 42 SW 40 41 42 43 44 45 0004 8900 9600 4900 7100 0003 0006 2800 0003 2000 3700 5400 7100 8800 3500 5500 7000 8900 0004 0004 5100 8000 0006 25 365/1 Woodmans Cottage 25 Spring Close 9 202/31 365/3 202/36 1392 365/2 8891 365/17 202/2 400/2 8487 St Mary's Church 5/23 4584 36 0682 8381 Drain 202/30 CHURCH LANE 7876 2/56 20 8900 7574 365/2 2772 Westcot Barton CP 5568 2968 1468 1267 365/3 9966 4666 202/ 0064 8964 0064 5064 5064 202/29 Drain Spring 1162 0961 11 202/31 202/56 1359 0054 0052 365/1 0052 5751 0050 Oathill Farm Oathill Lodge 264/8 0050 264/7 6046 The Folly 0044 0044 6742 264/8 202/32 264/7 3241 7841 0940 7640 1839 2938 Drain 3637 7935 0033 0032 0032 0033 1028 4429 El Sub Sta 3729 7226 202/11 3124 6423 6023 Pond 0022 202/30 365/28 8918 0218 2618 7817 9217 4216 0015 0015 Spring 8214 2014 Willowbrook Cottage 9610 Radford House Enstone CP Radford 0001 House 202/32 Charlotte Cottage 224/1 Spring Steeple Barton CP Reservoir Nelson's Cottage 0077 6400 2000 3900 6200 2400 5000 7800 0005 3800 6400 0001 1300 3900 6100 0005 RADFORD Convent Cottage 8700 2600 6400 2000 3900 0002 1300 24 Convent Cottage 0002 5000 7800 0005 3800 4800 6400 365/4 0001 3900 6100 0005 24 Holly Tree House Brook Close 0005 Brook Close White House Farm Radford Lodge 365/3 365/5 365/4 8889 Radford Farm 0084 6583 8083 0084 202/33 4779 0077 0077 0077 8976 3175 202/45 9471 224/1 Barton Leys Farm Pond 2669 8967 Mill House Kennels 7665 Pond 202/44 2864 6561 6360 Glyme The -

Long Cottage, 15 Fox Lane, Westcott Barton OX7 7BS

Long Cottage, 15 Fox Lane, Westcott Barton OX7 7BS Long Cottage, 15 Fox Lane, Westcott Barton OX7 7BS An attractive detached cottage set in beautiful gardens and offering spacious accommodation with off-road parking. The property briefly comprises an entrance hall, cloakroom, sitting room, dining room, kitchen, utility room, breakfast room, master bedroom, dressing room, shower room, guest bedroom, two further bedrooms, family bathroom and has central heating Westcott Barton is at the Western end of the Bartons. It has a Parish Church with Saxon origins and the well regarded Fox Inn. Within walking distance are the local Post Office/village shop and Primary School. The village sits just seven miles from Chipping Norton and the gateway to the Cotswolds. The location offers an ideal combination of rural values and tranquility together with the convenience of good commuting connections that enable relatively easy travel to further afield. Attractive Detached Cottage Sitting Room Dining Room Breakfast Room Kitchen & Utility Room Downstairs Cloakroom Master Bedroom "DoubleClick Insert Picture" Dressing Room Shower Room Guest Bedroom Two Further Bedrooms Family Bathroom Garage, Garden Shed & Greenhouse Guide Price: £750,000 Local Authority C Dn West Oxfordshire District Council Long Cottage, 15 Fox Lane, Dr essing Room Bedr oom 3.60m x 2.92m 3.32m x 2.93m Band F 11'10 x 9'7 Bedr oom Bedr oom 10'11 x 9'7 Westcott Barton, O X7 7BS 3.10m x 2.37m 2.72m x 2.37m 10'2 x 7'9 8'11 x 7'9 T C C W Tenure C C Freehold Bedr oom 4.97m x 3.53m 16'4 x 11'7 Additional Information C First Floor C Deddington c. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Initial Document Template

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Agenda Item No. 5 Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3REG County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4REG County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Discharge of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing CLASSM Change of Use – Agriculture to CND Discharge of Conditions Commercial PDET28 Agricultural Prior Approval HAZ Hazardous Substances Application PN56 Change of Use Agriculture to Dwelling PN42 Householder Application under Permitted POROW Creation or Diversion of Right of Way Development legislation. TCA Works to Trees in a Conservation Area PNT Telecoms Prior Approval TPO Works to Trees subject of a Tree NMA Non Material Amendment Preservation Order WDN Withdrawn FDO Finally Disposed Of Decision Description Decision Description Code Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection P1REQ Prior Approval Required P2NRQ Prior Approval Not Required P3APP Prior Approval Approved P3REF Prior Approval Refused P4APP Prior Approval Approved P4REF Prior Approval Refused West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 17/02767/CND Milton Under Wychwood APP Discharge of condition 5 Highway details (15/03128/OUT). Land South Of High Street Milton Under Wychwood Mr Andrew Smith 2. 18/02366/FUL Burford APP Affecting a Conservation Area Change of use of land for the permanent siting of one caravan for use by the Site Warden at the Wysdom Touring Park (Retrospective). -

Members of West Oxfordshire District Council 1997/98

MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL 2020/2021 (see Notes at end of document) FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT COUNCILLORS SEE www.westoxon.gov.uk/councillors Councillor Name & Address Ward and Parishes Term Party Expires ACOCK, JAKE 16 Hewitts Close, Leafield, Ascott and Shipton 2022 Oxon, OX29 9QN (Parishes: Ascott under Mob: 07582 379760 Wychwood; Shipton under Liberal Democrat Wychwood; Lyneham) [email protected] AITMAN, JOY *** 98 Eton Close, Witney, Witney East 2023 Oxon, OX28 3GB Labour (Parish: Witney East) Mob: 07977 447316 (N) [email protected] AL-YOUSUF, Bridleway End, The Green, Freeland and Hanborough 2021 ALAA ** Freeland, Oxon, (Parishes: Freeland; OX29 8AP Hanborough) Tel: 01993 880689 Conservative Mob: 07768 898914 [email protected] ASHBOURNE, 29 Moorland Road, Witney, Witney Central 2023 LUCI ** Oxon, OX28 6LS (Parish: Witney Central) (N) Mob: 07984 451805 Labour and Co- [email protected] operative BEANEY, 1 Wychwood Drive, Kingham, Rollright and 2023 ANDREW ** Milton under Wychwood, Enstone Oxon, OX7 6JA (Parishes: Enstone; Great Tew; Tel: 01993 832039 Swerford; Over Norton; Conservative [email protected] Kingham; Rollright; Salford; Heythrop; Chastleton; Cornwell; Little Tew) BISHOP, Glenrise, Churchfields, Stonesfield and Tackley 2021 RICHARD ** Stonesfield, Oxon, OX29 8PP (Parishes: Combe; Stonesfield; Tel: 01993 891414 Tackley; Wootton; Glympton; Mob: 07557 145010 Kiddington with Asterleigh; Conservative [email protected] Rousham) BOLGER, ROSA c/o Council Offices, -

Volume 08 Number 02

CAKE & COCKHORSE BA4NBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SPRING 1980. PRICE 50p. ISSN 0522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman: J. S.W. Gibson, Harts Cottage, Church Hanborough, Oxford. Magazine Editor: D. E. M. Fiennes, Woadmill Farm, Broughton, Banbury. Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: t Mrs N.M. Clifton, Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Senendone House, The Halt, Shenington, Banbury. Hanwell, Banbury, (Tel: Edge Hill 262) (Tel: Wroxton St. Mary 545) Hon. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, J. S. W. Gibson, Banbury Museum, Harts Cottage, Marlborough Road. Church Hanborough, (Tel: Banbury 2282) Oxford OX7 2AB. Hon. Archaeological Adviser: J.H. Fearon, Fleece Cottage, Bodic.nt.e, Einb1iry. Committee Members: Dr E. Asser, Miss C.G. Bloxham, Mrs G.W. Brinkworth, Mr A. DonaIdson, Mr N. Griffiths, Miss F.M. Stanton Details about the Society’s activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover Our cover picture shows Broughton church and its tower, and is reproduced, by kind permission of the artist, from “Churches of the Ban- bury Area n, by George Graham Walker. CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 8 Number 2 Spring 1980 J. P. Brooke-Little Editorial 25 D.E.M. Fiennes A Study in Family Relationships: 27 William Fiennes and Margaret Wykeham Nicholas Cooper Book Review: 'Broughton Castle 46 Sue Read and Icehouses: An Investigation at Wroxton 48 John Seagrave With a most becoming, but I dare to suggest, unnecessary modesty, the Editor of Take and Cockhorse" has invited me to write this Editorial as he himself is the author of the principal article in this issue. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner