Note If It's in the Game, Is It in the Game?: Examining League-Wide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

42 BAB IV DESKRIPSI OBJEK PENELITIAN 4.1 Sejarah EA Sport

BAB IV DESKRIPSI OBJEK PENELITIAN 4.1 Sejarah EA Sport Gambar 4.1 logo EA Sports Electronic Arts rnerupakan sebuah perusahaan multinasional yang menghasilkan berbagam macam produk multimedia. Didirikan pada tahun 1982. Perusahaan ini mempekerjakan 8.000 karyawannya pada tahun 2008. Bermarkas di Redwood City, California. Perusahaan ini didirikan pada tahun 1982. Nama itu sendiri mempunyai arti: “seniman elektronik” atau “seniman perangkat lunak”. Perusahaan yang didirikan pada tanggal 28 Mei 1982 oleh Trip Hawkins, menjadi perusahaan pelopor pembuat industri video game. Awalnya EA hanya merupakan penerbit video game rumahan yang berbentuk software, namun pada awal 1990-an perusahaan ini mulai mengembangkan game dan dengan didukung oleh konsol. EA kemudian berkembang dan tumbuh melalui akuisisinya dengan beberapa developer software lainnya yang telah sukses. Pada saat ini, EA menjadi perusahaan yang paling sukses dalam menerbitkan produk permainan olahraga. Adapun beberapa game yang telah 42 diterbitkan berdasarkan lisensi film yang telah popular seperti Harry Potter dan permainan lama yang masih berjalan seperti Need for Speed, Medal of Honor, The Sims, Battlefield, dan Burnout. Berikut ini adalah beberapa video game yang telah sukses dan familiar di masyarakat seperti FIFA series (1993-sekarang), James Bond series (1999-2005), The Sims Series (2007-2008), Star Wars : The Old Republic (2011), dan masih banyak lagi. Saat ini, EA telah mengembangkan dan menerbitkan game Sport diantaranya FIFA (sepak bola), Madden NFL (american football), NHL (ice hockey), NBA Live (basket), dan UFC 3 (seni beladiri). Adapun beberapa produk waralaba yang dihasilkan oleh EA diantaranya game Battlefield, Need for Speed, The Sims, Medal of Honor, serta beberapa waralaba baru seperti Crysis, Dragon Age, Mass Effect, Titanfall, Star Wars : Knights of the Old Republic, dan Army of Two. -

NIBC First Round Case NIBC Ele Ctro N Ic Arts Contents

NIBC First Round Case NIBC Ele ctro n ic Arts Contents 1. The Scenario 2. Background Information 3. Tasks & Deliverables A. Discounted Cash Flow Analysis B. Trading Comparables Analysis C. Precedent Transactions Analysis D. LBO Analysis E. Presentation 4. Valuation & Technical Guidance A. Discounted Cash Flow Analysis B. Trading Comparables Analysis C. Precedent Transactions Analysis D. LBO Analysis 5. Rules & Regulations 6. Appendix A: Industry Overview 7. Appendix B: Precedent Transactions Legal Disclaimer: The Case and all relevant materials such as spreadsheets and presentations are a copyright of the members of the NIBC Case Committee of the National Investment Banking Competition & Conference (NIBC), and intended only to be used by competitors or signed up members of the NIBC Competitor Portal. No one may copy, republish, reproduce or redistribute in any form, including electronic reproduction by “uploading” or “downloading”, without the prior written consent of the NIBC Case Committee. Any such use or violation of copyright will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. Need for Speed Madden NFL Electronic Arts Electronic Arts Welcome Letter Dear Competitors, Thank you for choosing to compete in the National Investment Banking Competition. This year NIBC has continued to expand globally, attracting top talent from 100 leading universities across North America, Asia, and Europe. The scale of the Competition creates a unique opportunity for students to receive recognition and measure their skills against peers on an international level. To offer a realistic investment banking experience, NIBC has gained support from a growing number of former organizing team members now on the NIBC Board, who have pursued investment banking careers in New York, Hong Kong, Toronto, and Vancouver. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

Game Developer Magazine

>> INSIDE: 2007 AUSTIN GDC SHOW PROGRAM SEPTEMBER 2007 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SAVE EARLY, SAVE OFTEN >>THE WILL TO FIGHT >>EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW MAKING SAVE SYSTEMS FOR CHANGING GAME STATES HARVEY SMITH ON PLAYERS, NOT DESIGNERS IN PANDEMIC’S SABOTEUR POLITICS IN GAMES POSTMORTEM: PUZZLEINFINITE INTERACTIVE’S QUEST DISPLAY UNTIL OCTOBER 11, 2007 Using Autodeskodesk® HumanIK® middle-middle- Autodesk® ware, Ubisoftoft MotionBuilder™ grounded ththee software enabled assassin inn his In Assassin’s Creed, th the assassin to 12 centuryy boots Ubisoft used and his run-time-time ® ® fl uidly jump Autodesk 3ds Max environment.nt. software to create from rooftops to a hero character so cobblestone real you can almost streets with ease. feel the coarseness of his tunic. HOW UBISOFT GAVE AN ASSASSIN HIS SOUL. autodesk.com/Games IImmagge cocouru tteesyy of Ubiisofft Autodesk, MotionBuilder, HumanIK and 3ds Max are registered trademarks of Autodesk, Inc., in the USA and/or other countries. All other brand names, product names, or trademarks belong to their respective holders. © 2007 Autodesk, Inc. All rights reserved. []CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2007 VOLUME 14, NUMBER 8 FEATURES 7 SAVING THE DAY: SAVE SYSTEMS IN GAMES Games are designed by designers, naturally, but they’re not designed for designers. Save systems that intentionally limit the pick up and drop enjoyment of a game unnecessarily mar the player’s experience. This case study of save systems sheds some light on what could be done better. By David Sirlin 13 SABOTEUR: THE WILL TO FIGHT 7 Pandemic’s upcoming title SABOTEUR uses dynamic color changes—from vibrant and full, to black and white film noir—to indicate the state of allied resistance in-game. -

Madden NFL 25 Makes Its Next-Gen Debut As Launch Title for Xbox One and Playstation 4

June 10, 2013 Madden NFL 25 Makes Its Next-Gen Debut as Launch Title for Xbox One and PlayStation 4 See It. Feel It. Live it. REDWOOD CITY, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Today Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: EA) has officially announced Madden NFL 25 will be coming as a launch title for Xbox One® all-in-one games and entertainment system from Microsoft, and the PlayStation®4 computer entertainment system. Madden NFL 25, powered by the new EA SPORTS IGNITE engine, ushers in the next generation of sports games by delivering the smartest, most realistic, most detailed version of the game in the franchise's 25 year history. "We've never been more ready for a console transition than we are right now," said Cam Weber, General Manager of American Football for EA SPORTS. "The development team is crafting the most impressive Madden NFL game we've ever made, and I'm extremely excited for fans to get their hands on it for themselves when the Xbox One and PS4 launch." Coupled with this announcement is the introduction of Adrian Peterson as the cover athlete for Madden NFL 25 on Xbox One and PlayStation 4. Peterson, the Minnesota Vikings running back, is a five-time Pro Bowler and the reigning NFL MVP. Last season Peterson came within 9 yards of breaking the NFL single-season rushing record set by Eric Dickerson. Madden NFL 25 on Xbox One and PlayStation 4 brings innovative new features such as True Step Locomotion, Player Sense, the War in the Trenches and more to create an experience that can only be found on next-generation consoles. -

H1 FY12 Earnings Presentation

H1 FY12 Earnings Presentation November 08, 2011 Yves Guillemot, President and Chief Executive Officer Alain Martinez, Chief Financial Officer Jean-Benoît Roquette, Head of Investor Relations Disclaimer This statement may contain estimated financial data, information on future projects and transactions and future business results/performance. Such forward-looking data are provided for estimation purposes only. They are subject to market risks and uncertainties and may vary significantly compared with the actual results that will be published. The estimated financial data have been presented to the Board of Directors and have not been audited by the Statutory Auditors. (Additional information is specified in the most recent Ubisoft Registration Document filed on June 28, 2011 with the French Financial Markets Authority (l’Autorité des marchés financiers)). 2 Summary H1 : Better than expected topline and operating income performance with strong growth margin improvement H1 : Across the board performance : Online − Casual − High Definition H2 : High potential H2 line-up for casual and passionate players, targeting Thriving HD, online platforms and casual segments H2 : Quality improves significantly Online : Continue to strenghten our offering and expertise FY12 : Confirming guidance for FY12 FY13 : Improvement in operating income and back to positive cash-flows 3 Agenda H1 FY12 performance H2 FY12 line-up and guidance 4 H1 FY12 : Sales Q2 Sales higher than guidance (146 M€ vs 99 M€) Across the board performance : Online − Casual − HD Benefits -

Pre-Conference Newsletter 2018

UPDATED Southwest Association of College and University Housing Officers FEBRUARY 18-20, 2018 SAN MARCOS, TX Registration is still See you in San Marcos! available at $240 Newsletter–Pre-conference 2018 REGISTER ONLINE NOW AT: www.swacuho.org SWACUHO 2018 Pre-conference 2018 In This Issue From The President .............................................................................3 From The President-Elect .....................................................................4 We want to hear from you! ................................................................5 Newsletter and Communications Committee .........................................5 Executive Board 2017–2018 ...............................................................6 Committee Chairs ...............................................................................7 Connections That Spark! SWACUHO 2018 .........................................9 Southern Placement Exchange is Happening Soon! .............................10 Greetings from Mid-Level Committee! ................................................11 Excellence in all That We Do .............................................................12 Give Back to the Local Community .....................................................13 Research, Assessment, and Information Committee .............................14 SWACUHO Texas State Director ........................................................15 Engaging in Research and Assessment the Kaizen Way ........................................................................16 -

EA Sports Challenge Series Powered by Virgin Gaming Launches Today

EA Sports Challenge Series Powered by Virgin Gaming Launches Today Virtual Athletes Compete for a Chance to Win Over $1-Million in Cash and Prizes in New Sports Video Game Tournament Exclusively on PlayStation 3 REDWOOD CITY, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Pro athletes will not be the only ones cashing in on their highlight reel moves in 2012, as Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS) today announced the EA SPORTS™ Challenge Series, a sports video game tournament series that will determine the most skilled Madden NFL 12, NHL®12 and FIFA 12 gamers. Powered by Virgin Gaming and exclusive to the PlayStation®3 (PS3TM) computer entertainment system, participants will compete for over $1- million in cash and prizes — the largest prize money of any console-based sports gaming tournament ever. Available online at www.virgingaming.com, new technology allows gamers to participate in the tournament online at their leisure by pairing up gamers playing on the site at the same time. "Virgin Gaming is earning a reputation for hosting the biggest gaming tournaments, but our members have been asking for even larger prize pools. That's what drove the creation of the EA SPORTS Challenge Series; the idea came from them," said Rob Segal, CEO of Virgin Gaming. "This is also the perfect opportunity to bring our unique tournament format to the masses, giving gamers the freedom to compete whenever they want, instead of according to a set schedule. Those who make it through the online qualifier phase will then earn a seat to play in the live finals for huge cash prizes and true e-sport star status." Players that want to compete in the EA SPORTS Challenge Series can register and participate immediately. -

Fifa-13-Xbox-360-Manual.Pdf

CCONTENTSontents COACHING TIP: SHIELDING 1 COMPLete ContROLS 22 Seasons To protect the ball from your marker, release and hold . Your player moves between 16 GaMEPLAY: TIPS anD TRICKS 22 CAREER his marker and the ball and tries to hold him off. 17 SettING UP THE GaME 25 SKILL GaMes SHooTING 18 PLAYING THE GaME 25 ONLINE Shoot/Volley/Header 19 EA SPORTS FootBALL CLUB 26 Kinect® Finesse/Placed shot + MatcH DAY 29 OTHER GaME ModeS Chip shot + 19 EA SPORTS FootBALL CLUB 30 CustoMIZE FIFA Flair shot (first time only) + 20 FIFA ULTIMate TeaM 31 MY FIFA 13 PassING Choose direction of pass/cross COMPLete ContROLS Short pass/Header (hold to pass to further player) NOTE: The control instructions in this manual refer to the Classic controller configuration. Lobbed pass (hold to determine distance) Once you’ve created your profile, select CUSTOMISE FIFA > SETTINGS > CONTROLS > XBOX Through ball (hold to pass to further player) 360 CONTROLLER to adjust your control preferences. Bouncing lob pass (hold to determine + AttacKING distance) DRIBBLING Lobbed through ball + (hold to pass to further player) Move player/Jog/Dribble Give and go + Sprint (hold) Finesse pass + Precision dribble (hold) Face up dribble + (hold) + COACHING TIP: GIVE AND GO Stop ball (when unmarked) (release) + To initiate a one-two pass, press while holding to make your player pass to a nearby teammate, and move to continue his run. Then press (ground pass), Stop ball and face goal (release) + (through ball), (lobbed pass), or + (lobbed through ball) to immediately return Shield ball (when marked) (release) + the ball to him, timing the pass perfectly to avoid conceding possession. -

Rock Music in Video Games

These three very different video games illustrate some of the many ways rock music has been incorporated into ROCK MUSIC recent video games. In the early days of video games, technological limitations prevented the use of prerecorded music: games simply didn’t have the necessary memory IN VIDEO space to store it, and consoles or computers didn’t have the hardware capabilities to play it back. But now, in the era of DVD and Blu-Ray discs, massive hard drives, and GAMES cloud computing, the amount and sound quality of game music is virtually unlimited. Even setting aside the many music-based games, such as the Rock Band, Guitar Hero, by William Gibbons and Dance Dance Revolution craze of the 2000s and early 2010s (discussed by Mark Katz in his “Backstage Pass”), we must acknowledge that rock has become an integral Consider these three moments from video games: (1) While part of the soundtracks to video games in a wide variety taking my “borrowed” car for a spin in Grand Theft Auto V of genres. (2013), I spend some time searching for the right in- game There are many reasons game designers and audio radio station. Elton John’s “Friday Night’s Alright for Fight- specialists might choose to include either well-known or ing” (1973) doesn’t seem quite right, and I switch through newly written rock music in their products. Most obvious Smokey Robinson’s “Cruisin’” (1979) and Rhianna’s “Only are the aesthetic benefits, or how music can enhance Girl (in the World)” (2010) before finally settling on Stevie players’ experiences by creating a particular emotional Wonder’s “Skeletons” (1987). -

Margaret W. Wong & Associates

TOLEDO COLUMBUS SALES: 419-870-6565 DETROIT, Since 1989. www. l a p r ensa1.com FREE! TOLEDO: TINTA CON SABOR Margaret W. Wong & Associates Attorneys at Law Tending to all your immigration needs, Margaret W Wong & Assoc. has 60 years of combined experience in immigration law. We assist clients with all types of work visas, green cards, J-1 waivers, I-601A, labor certifications, deportation cases, asy- CLEVELAND • LORAIN lum, motion to reopen, circuit court ap- COLUMBUS peals, and many others. Our firm has offices in Cleveland, OH; Ohio & Michigan’s Oldest & Largest Latino Weekly Columbus, OH; New York, NY; Chicago, IL; Atlanta, GA; and Nashville, TN. We have assisted clients within the state of Classified? Email [email protected] Ohio, throughout the rest of the USA, and internationally. Contact us today to get our experience and compassion on August/agosto 2, 2013 Weekly/Semanal 20 Páginas Vol. 53, No. 22 About Margaret W Wong: your side. • Author The Immigrant’s Way • U.S. News and World Report Se Habla Español Best Law Firm • Law Professor of Case EDUCATION IS THE ANSWER! Western Reserve University (216) 566-9908 • Ohio Leading Lawyer www.imwong.com • 2012 Ohio Asian Legend Cleveland Office: Atlanta Office: Chicago Office: 3150 Chester Ave, 5425 Peachtree Parkway 2002 S. Wentworth Ave., Suite 200 Cleveland, OH 44114 Norcross, GA 30092 Chicago, IL 60616 Phone: (216) 566-9908 Phone: (678) 906-4061 Phone: (312) 463-1899 Fax: (216) 566-1125 New York Office: Nashville Office: Columbus Office: 139 Centre Street, By Appointment Only By Appointment Only PH112, 301 S. -

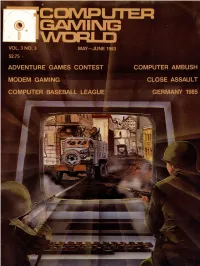

Computer Gaming World Issue

VOL. 3 NO. 3 MAY -JUN 1983 FEATURES CLOSE ASSAULT 6 Review and Analysis Bob Proctor FillADVENTURE GAME CONTEST 7 in the Crossword Puzzle COMPUTER AMBUSH 10 Review and Analysis David Long PINBALL CONSTRUCTION SET 12 A Toy for AH Ages John Besnard WHEN SUPERPOWERS COLLIDE 14 Part 1 Germany 1985 Maj Mike Chamberlain GALACTIC ATTACK! 19 Sir-tech's Space Combat Game Dick Richards TELE-GAMING 20 A New Column Patricia Fitzgibbons THE NAME OF THE GAME 22 A New Column by Jon Freeman TWO COMPUTER BASEBALL LEAGUES 23 Two leagues for SSI's Computer Baseball Stanley Greenlaw CHESS 7.0 33 Odesta's Program Evaluated Floyd Mathews Departments Inside the Industry 2 Hobby and Industry News 3 Taking a peek 4 Silicon Cerebrum 13 Atari Arena 28 The Learning Game 30 Microcomputer Mathemagic 34 Route 80 35 Micro-Reviews 36 Reader Input Device 47 INSIDE THE INDUSTRY by Dana Lombardy, Associate Publisher Game Merchandising This issue we're going to look at the order them in the quantities they can with one of his new games, when another nearly thirty computer games that have handle. publisher may be selling twice as many been on the best-sellers lists for months. of his slowest-selling game! Because they As you can see, wholesalers are im- There was a time when a new game really are in the "middle" of things, portant to the software industry. And program came out, sold out, and then wholesalers can provide a much more because of their unique position, they the next new program came along to accurate picture of the overall software have a perspective on what's happening replace it and repeat the cycle.