University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan ALIENATION and IDENTITY: a COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS of BLUE-COLLAR and COUNTER-CULTURE VALUES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s}". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man. -

The Anti-Heroic Figure in American Fiction of the 1960S 1

Notes Chapter 1 The Rebel with a Cause? The Anti-Heroic Figure in American Fiction of the 1960s 1. Ihab Hassan, “The Anti-Hero in Modern British and American Fiction,” in Rumors of Change (1959; repr., Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995), 55–67, p. 55. 2. David Galloway, The Absurd Hero in American Fiction (Austin: University of Texas Printing, 1970), 9. 3. Philip Rice and Patricia Waugh, “Histories and Textuality,” in Modern Literary Theory, ed. Philip Rice and Patricia Waugh, rev. ed. (1989; repr., London: Arnold, 2001), 252–256, p. 253. 4. Helen Weinberg, The New Novel in America: The Kafka Mode in Contemporary Fiction (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1970), 11. 5. Ibid., 55. 6. Tony Tanner, City of Words (London: Jonathan Cape, 1971), 146. 7. There are of course important novels written in the 1960s that can be classified as metafiction or surfiction such as Thomas Pynchon’s V (1963), The Crying of Lot 49 (1967), and Richard Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America (1967). However, the majority of significant novels written during the 1960s still maintain an (at least ostensible) adherence to a more naturalist form and structure. 8. Thomas Berger, Little Big Man, rev. ed. (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1965; London: Harvill Press, 1999), 312. Citations are to the Harvill Press edition. 9. John Barth, “The Literature of Exhaustion,” in The Friday Book: Essays and Other Nonfiction (1984; Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1997), 62–76, p. 62. 10. Louis D. Rubin Jr., “The Great American Joke,” in What’s So Funny? Humor in American Culture, ed. -

An ERIC Paper

An ERIC Paper ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION: THE FREE SCHOOL MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES By Allen Graubard September 1972 /ssued by the ER/C Clearinghouse on Media and Technolool Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 U.S. DEPARTMLNT DF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION: THE FREE SCHOOL MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES By Allen Graubard September 1972 Issued by the ERIC Clearinghouse on Media and Technology Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Experience both within andoutside thc system makes Allen Graubard a knowledgeable author for such a paper as this. A Harvard man, Dr. Graubard was director of The Community School, a free elementary and high school in Santa Barbara, California. He served as director of the New Schools Directory Project, funded by the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and has been an editor for New Schools Exchange Newsletter. Most recently, Dr. Graubard was on assignment as Special Assistant to the President for Community-Based Educational Programs at Goddard College, Plainfield, Vermont. TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Author Introduction 1 The Free School Movement: Theory and Practice 2 Pedagogical Source 2 Political Source 3 The Current State of Free Schools 4 Kinds of Free Schools 6 Summerhillian 6 Parent-Teacher Cooperative Elementary 6 Free High Schools 6 Community Elementary 7 Political and Social Issues 9 Wain the System: Some Predictions 11 Resources 13 Journals 13 Books and Articles 13 Useful Centers, Clearinghouses, and People Involved with Free Schools 15 4 INTRODUCTION Approximately nine out of every ten children in the United States attend the public schools. -

Pete* Mcknight Selected As Lovej Oy

: 4 _ ¦' *¦ ** —* i" n r- r-- -- --r »~r _- <- _- _- «- - » - _¦ You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth. THE PROPHET "On Children" Kahlil Gibran • Friday, October 8 e 7 :00 - 8:00 P.M. Open House - Refreshments will be served. Bix- Pete* McKnight Selected ler Art and Music Center. 8 :15 P.M. Guy P. Gannett Lecture. Ralph E. Lapp, Nuclear Scientist and Author "Can a Democracy Survive Science?" As Lovej oy Recipient Nobody knows better than Dr. Lapp the wide gulf between the science laboratory and the public's awareness of what is going on be- Colbert A. McKnight, editor of the Charlotte (N.C. ) Observer, hind the scenes. Author of ten books and many articles, Dr. Lapp has will receive Colby College's 1965 Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award at a played a major contributory role in the developments that have convocation November 4. marked the atomic age - from the Manhattan Project to the reality McKnight served as a war correspondent for the "Baltimore Sun" of the H-bomb. Given Auditorium. and "Business Week Magazine" before moving to the "Charlotte (N.C.) News." In 1955, he was named editor of the Observer. He Saturday, October 9 has received numerous journalistic awards. The Lovejoy Award is annually given, to a newsman who has 8 :00 - 10:30 A.M. Registration, For those who have not received "contributed to the nation's journalistic achievement" and shows their tickets by registering in advance. Main Desk, Miller Library. "integrity craftsmanship and character." 8:30 - 10:30 A.M. -

PAUL GOODMAN (1911-1972) Edgar Z

The following text was originally published in Prospects : the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO : International Bureau of Education), vol . XXIII, no . 3/4, June 1994, p. 575-95. ©UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 1999 This document may be reproduced free of charge as long as acknowledgement is made of the source. PAUL GOODMAN (1911-1972) Edgar Z. Friedenberg1 Paul Goodman died of a heart attack on 2 August 1972, a month short of his 61st birthday. This was not wholly unwise. He would have loathed what his country made of the 1970s and 1980s, even more than he would have enjoyed denouncing its crassness and hypocrisy. The attrition of his influence and reputation during the ensuing years would have been difficult for a figure who had longed for the recognition that had eluded him for many years, despite an extensive and varied list of publications, until Growing up absurd was published in 1960, which finally yielded him a decade of deserved renown. It is unlikely that anything he might have published during the Reagan-Bush era could have saved him from obscurity, and from the distressing conviction that this obscurity would be permanent. Those years would not have been kind to Goodman, although he was not too kind himself. He might have been and often was forgiven for this; as well as for arrogance, rudeness and a persistent, assertive homosexuality—a matter which he discusses with some pride in his 1966 memoir, Five years, which occasionally got him fired from teaching jobs. However, there was one aspect of his writing that the past two decades could not have tolerated. -

1960S Futurism and Post-Industrial Theory A

"More than Planners, Less than Utopians:" 1960s Futurism and Post-Industrial Theory A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jasper Verschoor August 2017 © 2017 Jasper Verschoor. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled "More than Planners, Less than Utopians:" 1960s Futurism and Post-Industrial Theory by JASPER VERSCHOOR has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Kevin Mattson Connor Study Professor of Contemporary History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT VERSCHOOR, JASPER, Ph.D., August 2017, History "More than Planners, Less than Utopians:" 1960s Futurism and Post-Industrial Theory Director of Dissertation: Kevin Mattson This dissertation studies the ideas of a group of thinkers described by Time Magazine in 1966 as “Futurists.” The American sociologist Daniel Bell, the French political philosopher Bertrand de Jouvenel, and the physicist Herman Kahn argued that the future could not be predicted but that forecasting certain structural changes in society could help avoid social problems and lead to better planning. In order to engage in such forecasting Jouvenel founded Futuribles, an international group that facilitated discussion about the future of advanced industrial societies. Bell chaired a Commission on the year 2000 that aimed to anticipate social problems for policy makers. The dissertation also focuses on work done by Kahn and others at the RAND Corporation and the Hudson Institute. The origin of 1960s futurism is traced to debates held under the auspices of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, especially ideas about the “end of ideology.” The supposed exhaustion of left and right-wing political ideologies produced a desire for new theories of social change. -

Agency and Other Anarchist Themes in Paul Goodman's Work

Agency and Other Anarchist Themes In Paul Goodman's Work Kevin Carson Center for a Stateless Society STRUCTURAL PREEMPTION In Growing Up Absurd, we see the first statement of a theme that continues to reappear throughout Goodman's work. ...people are so bemused by the way business and politics are carried on at present with all their intricate relationships, that they have ceased to be able to imagine alternatives.... ...[T]he system pre-empts the available means and capital; it buys up as much of the intelligence as it can and muffles the voices of dissent; and then it irrefutably proclaims that itself is the only possibility of society, for nothing else is thinkable.1 In People or Personnel, similarly: ...[T]he inevitability of centralism will be self-proving. A system destroys its competitors by pre-empting the means and channels, and then proves that it is the only conceivable mode of operating.2 So even though the system is the result of deliberate human action and serves the interests of one group of human beings at the expense of another, it is treated as an inevitable fact of nature. As an example of such "pre-empting of the means and the brains by the organization," he cites higher education, where only faculty are chosen that are "safe" to the businessmen trustees or the politically appointed regents and these faculties give out all the degrees and licenses and union cards to the new generation of students, and only such universities can get Foundation or government money for research, and research is incestuously staffed by the same sponsors and according to the same policy, and they allow no one but those they choose, to have access to either the classroom or expensive apparatus: it will then be claimed that there is no other learning or professional competence....3 1 Paul Goodman, Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized Society (New York Vintage Books, 1956), x. -

The Anarchist Writings of Paul Goodman

Redrawing The Line: The Anarchist Writings of Paul Goodman Paul Comeau Spring, 2012 A review of Drawing The Line Once Again: Paul Goodman’s Anarchist Writings, PM Press, 2010, 122 pages, trade paperback, $14.95 While relatively unknown today, Paul Goodman was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. In books like Growing Up Absurd, published in 1960, Goodman captured the zeitgeist of his era, catapulting himself to the forefront of American intellectual life as one of the leading dissident thinkers inspiring the burgeoning New Left. Goodman, who passed away in 1972 at the age of 60, was an iconoclastic radical with a wide ranging scope of intellectual vision and a multi-faceted character. He was an anarchist, a family man, openly bisexual in a sexually repressive era, a psychologist (one of the founders of Gestalt Therapy), and a poet. He saw himself as a classical man of letters, and at his peak output, released nearly a book ayear. PM Press has recently reprinted some of Goodman’s writings in three volumes. The first, Drawing The Line Once Again: Paul Goodman’s Anarchist Writings, col- lects short essays from throughout Goodman’s lifetime including “The May Pam- phlet,” one of his earliest pieces. Many of these pieces were later incorporated into his longer works. “The May Pamphlet” is in many ways Goodman’s manifesto, outlining someof his basic principles. From advocating a free society, to discussing the nature of language, to an examination of the education system and its function as a system of coercion, the themes and principles outlined in it are revisited time and again throughout his writings. -

University Microfilms. a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

I I 72-4474 EDMONDS, Victor Earl, 1942- DEFINITION OF THE FREE SCHOOLS MOVEMENT IN AMERICA, 1967-1971. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, curriculum development University Microfilms. A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan (c) Copyright by Victor Earl Edmonds 1971 DEFINITION OF THE FREE SCHOOLS MOVEMENT IN AMERICA 1967-1971 DISSERTATION presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University 3y Victor Earl Edmonds, B.S. in Ed., M.A. The Ohio State University 197.1 Approved by c Adviser College of Education PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to Professor Paul ICLohr for making this possible. And to Eric for nearly making it impossible by continually reminding me that kids are more important than education. Thanks to Faith for taking care of everything else in our lives while I wrote. And thanks to my sister Nina for much of the work on the bibliog~ raphy• VITA March 24, 1971* . • Born - Covington, Kentucky 1 9 6 4 . ........... .. B.S. in Ed., University of Dayton, Dayton, Ohio 1964-1968 ......... Teacher and Counselor, Grades 6-12, Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Chicago 1968-1969 ......... Counselor, The Ohio Youth Commission, Columbus, Ohio 1969. ....... M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1969-1971 ..... Teaching Associate, Department of Curriculum and Foundations, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio PUBLICATIONS “Rock Music and the Political Scene." Interface, No. 1, Fall, 1968. “The Beaties' New Album." Interface, No. 2, Winter, 1969, FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: Curriculum Studies in Curriculum: Professors Paul R. -

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

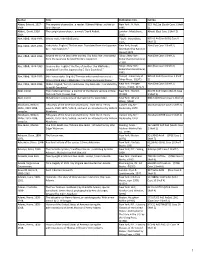

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

COMPULSORY MISEDUCATION Paul Goodman

COMPULSORY MISEDUCATION Paul Goodman When at a meeting, I offer that perhaps we already have too much formal schooling and that under present conditions, the more we get the less education we will get, the others look at me oddly and proceed to discuss how to get more money for schools and how to upgrade the schools. I realize suddenly that I am confronting a mass superstition. The mass superstition in question, which is the target of this classic and iconoclastic work, is that education can only be achieved by the use of institutions like the school. Paul Goodman argues that on the contrary subjecting young people to institutionalized learning stunts and distorts their natural intellectual development makes them hostile to the very idea of education and finally turns out regimented competitive citizens likely only to aggravate our current social ills. He prescribes an increased involvement in the natural learning patterns of family and community and of the sort of relationships fostered in master-apprentice situations. A great neurologist tells me that the puzzle is not how to teach reading, but why some children fail to learn to read. Given the amount of exposure that any urban child gets, any normal animal should spontaneously catch on to the code. What prevents it is almost demonstrable that, for many children, it is precisely going to school that prevents -- because of the school’s alien style, banning of spontaneous interest, extrinsic rewards and punishments. (In many underprivileged schools, the IQ steadily falls the longer they go to school). Many of the backward readers might have had a better chance on the streets Compulsory Miseducation Paul Goodman Paul Goodman was born in New York City in 1911, graduated from City College and received his PhD.