Atopic Children in General Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emerging Evidence for a Central Epinephrine-Innervated A1- Adrenergic System That Regulates Behavioral Activation and Is Impaired in Depression

Neuropsychopharmacology (2003) 28, 1387–1399 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0893-133X/03 $25.00 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Perspective Emerging Evidence for a Central Epinephrine-Innervated a1- Adrenergic System that Regulates Behavioral Activation and is Impaired in Depression ,1 1 1 1 1 Eric A Stone* , Yan Lin , Helen Rosengarten , H Kenneth Kramer and David Quartermain 1Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA Currently, most basic and clinical research on depression is focused on either central serotonergic, noradrenergic, or dopaminergic neurotransmission as affected by various etiological and predisposing factors. Recent evidence suggests that there is another system that consists of a subset of brain a1B-adrenoceptors innervated primarily by brain epinephrine (EPI) that potentially modulates the above three monoamine systems in parallel and plays a critical role in depression. The present review covers the evidence for this system and includes findings that brain a -adrenoceptors are instrumental in behavioral activation, are located near the major monoamine cell groups 1 or target areas, receive EPI as their neurotransmitter, are impaired or inhibited in depressed patients or after stress in animal models, and a are restored by a number of antidepressants. This ‘EPI- 1 system’ may therefore represent a new target system for this disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology (2003) 28, 1387–1399, advance online publication, 18 June 2003; doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300222 Keywords: a1-adrenoceptors; epinephrine; motor activity; depression; inactivity INTRODUCTION monoaminergic systems. This new system appears to be impaired during stress and depression and thus may Depressive illness is currently believed to result from represent a new target for this disorder. -

Marie Louise De Bruin Drug Induced Arrhythmias

Marie Louise De Bruin drug induced arrhythmias Quantifying the problem Cover design: Tom Frantzen CIP-gegevens Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag De Bruin, Marie Louise Drug-induced arrhythmias, quantifying the problem / Marie Louise De Bruin Thesis Utrecht - with ref.- with summary in Dutch ISBN: 90-808203-3-4 © Marie Louise De Bruin drug-induced arrhythmias, quantifying the problem Geneesmiddel-geïnduceerde hartritmestoornissen, kwantificering van het probleem (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Utrecht op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. dr W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 1 december 2004 des namiddags om 14.30 uur door Marie Louise De Bruin Geboren op 1 april 1974 te Haarlem promotores Prof. dr H.G.M. Leufkens Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (UIPS), Department of Pharmaco- epidemiology and Pharmacotherapy, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands Prof. dr A.W. Hoes Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands The work in this thesis was performed at the Department of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacotherapy of the Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (Utrecht) and the Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care (Utrecht), in collabo- ration with the PHARMO Institute (Utrecht), the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb (‘s-Hertogenbosch), the WHO-Uppsala Monitoring Centre (Uppsala, Sweden) and the Academic Medical Center (Amsterdam). The research presented in this thesis was funded by the Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, and an unrestricted grant from the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board. The study presented in chapter 3.1 was funded by an unrestricted grant from Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium. -

Cocaine Intoxication and Hypertension

THE EMCREG-INTERNATIONAL CONSENSUS PANEL RECOMMENDATIONS Cocaine Intoxication and Hypertension Judd E. Hollander, MD From the Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. 0196-0644/$-see front matter Copyright © 2008 by the American College of Emergency Physicians. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.11.008 [Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:S18-S20.] with cocaine intoxication is analogous to that of the patient with hypertension: the treatment should be geared toward the Cocaine toxicity has been reported in virtually all organ patient’s presenting complaint. systems. Many of the adverse effects of cocaine are similar to When the medical history is clear and symptoms are mild, adverse events that can result from either acute hypertensive laboratory evaluation is usually unnecessary. In contrast, if the crisis or chronic effects of hypertension. Recognizing when the patient has severe toxicity, evaluation should be geared toward specific disease requires treatment separate from cocaine toxicity the presenting complaint. Laboratory evaluation may include a is paramount to the treatment of patients with cocaine CBC count; determination of electrolyte, glucose, blood urea intoxication. nitrogen, creatine kinase, and creatinine levels; arterial blood The initial physiologic effect of cocaine on the cardiovascular gas analysis; urinalysis; and cardiac marker determinations. system is a transient bradycardia as a result of stimulation of the Increased creatine kinase level occurs with rhabdomyolysis. vagal nuclei. Tachycardia typically ensues, predominantly from Cardiac markers are increased in myocardial infarction. Cardiac increased central sympathetic stimulation. Cocaine has a troponin I is preferred to identify acute myocardial13 infarction. cardiostimulatory effect through sensitization to epinephrine A chest radiograph should be obtained in patients with and norepinephrine. -

Atopic Children and Use of Prescribed Medication: a Comprehensive Study in General Practice

RESEARCH ARTICLE Atopic children and use of prescribed medication: A comprehensive study in general practice David H. J. Pols1*, Mark M. J. Nielen2, Arthur M. Bohnen1, Joke C. Korevaar2, Patrick J. E. Bindels1 1 Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2 NIVEL, Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research, Utrecht, The Netherlands a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 Purpose A comprehensive and representative nationwide general practice database was explored to study associations between atopic disorders and prescribed medication in children. OPEN ACCESS Citation: Pols DHJ, Nielen MMJ, Bohnen AM, Korevaar JC, Bindels PJE (2017) Atopic children Method and use of prescribed medication: A All children aged 0±18 years listed in the NIVEL Primary Care Database in 2014 were comprehensive study in general practice. PLoS ONE 12(8): e0182664. https://doi.org/10.1371/ selected. Atopic children with atopic eczema, asthma and allergic rhinitis (AR) were journal.pone.0182664 matched with controls (not diagnosed with any of these disorders) within the same general Editor: Anthony Peter Sampson, University of practice on age and gender. Logistic regression analyses were performed to study the differ- Southampton School of Medicine, UNITED ences in prescribed medication between both groups by calculating odds ratios (OR); 93 dif- KINGDOM ferent medication groups were studied. Received: March 24, 2017 Accepted: July 13, 2017 Results Published: August 24, 2017 A total of 45,964 children with at least one atopic disorder were identified and matched with Copyright: © 2017 Pols et al. This is an open controls. Disorder-specific prescriptions seem to reflect evidence-based medicine guide- access article distributed under the terms of the lines for atopic eczema, asthma and AR. -

Evaluating Onco-Geriatric Scores and Medication Risks to Improve Cancer Care for Older Patients

Evaluating onco-geriatric scores and medication risks to improve cancer care for older patients Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von IMKE ORTLAND aus Quakenbrück Bonn 2019 Angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn. Diese Dissertation ist auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn elektronisch publiziert. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:5-58042 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Jaehde Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Andreas Jacobs Tag der Promotion: 28. Februar 2020 Erscheinungsjahr: 2020 Danksagung Auf dem Weg zur Promotion haben mich viele Menschen begleitet und in ganz unterschiedlicher Weise unterstützt. All diesen Menschen möchte ich an dieser Stelle ganz herzlich danken. Mein aufrichtiger Dank gilt meinem Doktorvater Prof. Dr. Ulrich Jaehde für das in mich gesetzte Vertrauen, sowie für die Überlassung dieses spannenden Dissertationsthemas. Die uneingeschränkte Unterstützung, wertvollen Diskussionen und die mitreißende Begeisterung für die Wissenschaft haben mich während aller Phasen der Dissertation stets motiviert, unterstützt und sehr viel Wertvolles gelehrt. Prof. Dr. Andreas Jacobs danke ich herzlich für die Initiierung dieses interessanten Projekts, für die stetige Begeisterung und Unterstützung, sowie für das mir entgegengebrachte Vertrauen. Die ausgezeichnete Zusammenarbeit mit dem Johanniter Krankenhaus Bonn hat ganz maßgeblich zum Gelingen dieser Arbeit beigetragen. Auch danke ich Prof. Dr. Andreas Jacobs herzlich für die Bereitschaft, das Koreferat dieser Arbeit zu übernehmen. Ebenfalls danke ich herzlich Prof. Dr. Yon-Dschun Ko für seine fortwährende Motivation und seinen Einsatz, sowie für das mir geschenkte Vertrauen, dieses Projekt am Johanniter Krankenhaus zu realisieren. Ebenfalls danke ich Prof. -

Medication Risks in Older Patients with Cancer

Medication risks in older patients with cancer 1 Medication risks in older patients (70+) with cancer and their association with therapy-related toxicity Imke Ortland1, Monique Mendel Ott1, Michael Kowar2, Christoph Sippel3, Yon-Dschun Ko3#, Andreas H. Jacobs2#, Ulrich Jaehde1# 1 Institute of Pharmacy, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, University of Bonn, An der Immenburg 4, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Department of Geriatrics and Neurology, Johanniter Hospital Bonn, Johanniterstr. 1-3, 53113 Bonn, Germany 3 Department of Oncology and Hematology, Johanniter Hospital Bonn, Johanniterstr. 1-3, 53113 Bonn, Germany # equal contribution Corresponding author Ulrich Jaehde Institute of Pharmacy University of Bonn An der Immenburg 4 53121 Bonn, Germany Phone: +49 228-73-5252 Fax: +49-228-73-9757 [email protected] Medication risks in older patients with cancer 2 Abstract Objectives To evaluate medication-related risks in older patients with cancer and their association with severe toxicity during antineoplastic therapy. Methods This is a secondary analysis of two prospective, single-center observational studies which included patients ≥ 70 years with cancer. The patients’ medication was investigated regarding possible risks: polymedication (defined as the use of ≥ 5 drugs), potentially inadequate medication (PIM; defined by the EU(7)-PIM list), and relevant potential drug- drug interactions (rPDDI; analyzed by the ABDA interaction database). The risks were analyzed at two different time points: before and after start of cancer therapy. Severe toxicity during antineoplastic therapy was captured from medical records according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). The association between Grade ≥ 3 toxicity and medication risks was evaluated by univariate regression. -

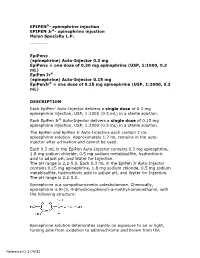

Epipen Injection Label

EPIPEN®- epinephrine injection EPIPEN Jr®- epinephrine injection Mylan Specialty L.P. ---------- EpiPen® (epinephrine) Auto-Injector 0.3 mg EpiPen® = one dose of 0.30 mg epinephrine (USP, 1:1000, 0.3 mL) EpiPen Jr® (epinephrine) Auto-Injector 0.15 mg EpiPenJr® = one dose of 0.15 mg epinephrine (USP, 1:2000, 0.3 mL) DESCRIPTION Each EpiPen® Auto-Injector delivers a single dose of 0.3 mg epinephrine injection, USP, 1:1000 (0.3 mL) in a sterile solution. Each EpiPen Jr® Auto-Injector delivers a single dose of 0.15 mg epinephrine injection, USP, 1:2000 (0.3 mL) in a sterile solution. The EpiPen and EpiPen Jr Auto-Injectors each contain 2 mL epinephrine solution. Approximately 1.7 mL remains in the auto- injector after activation and cannot be used. Each 0.3 mL in the EpiPen Auto-Injector contains 0.3 mg epinephrine, 1.8 mg sodium chloride, 0.5 mg sodium metabisulfite, hydrochloric acid to adjust pH, and Water for Injection. The pH range is 2.2-5.0. Each 0.3 mL in the EpiPen Jr Auto-Injector contains 0.15 mg epinephrine, 1.8 mg sodium chloride, 0.5 mg sodium metabisulfite, hydrochloric acid to adjust pH, and Water for Injection. The pH range is 2.2-5.0. Epinephrine is a sympathomimetic catecholamine. Chemically, epinephrine is B-(3, 4-dihydroxyphenyl)-a-methyl-aminoethanol, with the following structure: Epinephrine solution deteriorates rapidly on exposure to air or light, turning pink from oxidation to adrenochrome and brown from the Reference ID: 3176782 formation of melanin. -

Patients on Beta-Blockers

Systemic Allergic & Immunoglobulin Disorders Bryan L. Martin, DO, MMAS, FACAAI, FAAAAI, FACP, FACOI Emeritus Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics President, American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Disclosures . None 2 Objectives . Pass the boards! . Recognize anaphylaxis and understand the new guidelines for the treatment of anaphylaxis . Compare and contrast anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions 3 The Patient . 45 year old woman goes to lunch with her friends . While eating she develops GI upset, dizziness, shortness of breath and hives . Her friends drive her to your nearby clinic Initial Evaluation . Your nurse gets the history of sudden onset of GI upset, dizziness, shortness of breath and hives while eating a shrimp salad. The patient now has audible wheezing, tachycardia, and a blood pressure of 110/60 . Your initial response . Take a detailed history of everything the patient had to eat for lunch . Ask if she has a history of any medical issues such as asthma, diabetes or heart disease . Give nebulized beta agonist . Give 50 mg of oral diphenhydramine . Give 0.3 ml of IM epinephrine Anaphylaxis presentation . Your nurse gets the history of sudden onset of GI upset, dizziness, shortness of breath and hives while eating lunch. The patient now has audible wheezing, tachycardia, and a blood pressure of 110/60 . Your initial response . Take a detailed history of everything the patient had to eat for lunch . Ask if she has a history of any medical issues such as asthma, diabetes or heart disease . Give nebulized beta agonist . Give 50 mg of oral diphenhydramine . Give 0.3 ml of IM epinephrine Initial Response to anaphylaxis . -

Diphenhydramine (Systemic) Epinephrine (Systemic)

DIPHENHYDRAMINE (SYSTEMIC) ^ Diphenhist [OTC] see DiphenhydrAMINE (Systemic) on page 34 Insomnia, occasional: Oral: Children 2 to 12 years, weighing 10 to 50 kg (off-label use): DiphenhydrAMINE (Systemic) Limited data available: 1 mg/kg administered 30 minutes before bedtime; maximum single dose: 50 mg (Russo, 1976) Brand Names: US Aler-Dryl [OTC]; Allergy Relief Childrens Children ≥12 years and Adolescents: Refer to adult dosing. [OTC]; Allergy Relief [OTC]; Altaryl [OTC]; Anti-Hist Allergy [OTC]; Motion sickness: Banophen [OTC]; Benadryl Allergy Childrens [OTC]; Benadryl Prophylaxis: Oral: Allergy [OTC]; Benadryl Dye-Free Allergy [OTC]; Benadryl [OTC]; Manufacturer's labeling: Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Complete Allergy Medication [OTC]; Complete Allergy Relief [OTC]; Note: Administer 30 minutes before motion Dicopanol FusePaq; Dicopanol RapidPaq; Diphen [OTC]; Diphenh- Weight-directed dosing: 5 mg/kg/day divided into 3 to 4 doses; ist [OTC]; Genahist [OTC]; Geri-Dryl [OTC]; GoodSense Allergy maximum: 300 mg daily Relief [OTC]; Naramin [OTC]; Nighttime Sleep Aid [OTC]; Nytol Fixed dosing: 12.5 to 25 mg 3 to 4 times daily Maximum Strength [OTC]; Nytol [OTC]; Ormir [OTC]; PediaCare Alternate dosing: Children 2 to 12 years: Limited data available: Childrens Allergy [OTC]; Pharbedryl; Pharbedryl [OTC]; Q-Dryl 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/dose every 6 hours; maximum single dose: [OTC]; QlearQuil Nighttime Allergy [OTC]; Quenalin [OTC] [DSC]; 25 mg. First dose should be administered 1 hour before travel Scot-Tussin Allergy Relief [OTC]; Siladryl -

Oral Immunosuppressive Drugs in the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis

Oral immunosuppressive drugs in the treatment of atopic dermatitis IMPROVING PERFORMANCE AND SAFETY FLOOR M. GARRITSEN Colofon Oral immunosuppressive drugs in the treatment of atopic dermatitis Improving performance and safety Thesis with a summary in Dutch, Utrecht University, the Netherlands © Floor Garritsen, 2018 No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author. ISBN: 978-90-393-6931-9 Cover design and layout: Die Jongens Printed and published by: Proefschriftmaken.nl Oral immunosuppressive drugs in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: improving performance and safety Orale immunosuppressiva bij de behandeling van constitutioneel eczeem: het verbeteren van effectiviteit en veiligheid (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 8 februari 2018 des middags te 2.30 uur door Floralie Maria Garritsen geboren op 22 oktober 1986 te Beek en Donk Promotor: Prof. dr. C.A.F.M. Bruijnzeel-Koomen Copromotoren: Dr. M.S. de Bruin-Weller Dr. M.P.H. van den Broek Table of contents Chapter 1 General introduction 7 Part I – Qualitative and quantitative exploration of oral immunosuppressive drug use in the Netherlands Chapter 2 Ten years experience with oral immunosuppressive treatment 23 in adult patients with atopic dermatitis in two -

Xylocaine® (Lidocaine Hcl and Epinephrine Injection, USP) for Infiltration and Nerve Block Rx Only

XYLOCAINE MPF- lidocaine hydrochloride injection, solution XYLOCAINE - lidocaine hydrochloride injection, solution XYLOCAINE MPF- lidocaine hydrochloride,epinephrine bitartrate injection, solution XYLOCAINE - lidocaine hydrochloride,epinephrine bitartrate injection, solution Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC ---------- Xylocaine® (lidocaine HCl Injection, USP) Xylocaine® (lidocaine HCl and epinephrine Injection, USP) For Infiltration and Nerve Block Rx only DESCRIPTION Xylocaine (lidocaine HCl) Injections are sterile, nonpyrogenic, aqueous solutions that contain a local anesthetic agent with or without epinephrine and are administered parenterally by injection. See INDICATIONS AND USAGE section for specific uses. Xylocaine solutions contain lidocaine HCl, which is chemically designated as acetamide, 2- (diethylamino)-N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-, monohydrochloride and has the molecular wt. 270.8. Lidocaine HCl (C 14H 22N 2O • HCl) has the following structural formula: Epinephrine is (-) -3, 4-Dihydroxy-α-[(methylamino) methyl] benzyl alcohol and has the molecular wt. 183.21. Epinephrine (C 9H 13NO 3) has the following structural formula: Dosage forms listed as Xylocaine-MPF indicate single dose solutions that are Methyl Paraben Free (MPF). Xylocaine MPF is a sterile, nonpyrogenic, isotonic solution containing sodium chloride. Xylocaine in multiple dose vials: Each mL also contains 1 mg methylparaben as antiseptic preservative. The pH of these solutions is adjusted to approximately 6.5 (5.0 to 7.0) with sodium hydroxide and/or hydrochloric acid. Xylocaine MPF with Epinephrine is a sterile, nonpyrogenic, isotonic solution containing sodium chloride. Each mL contains lidocaine hydrochloride and epinephrine, with 0.5 mg sodium metabisulfite as an antioxidant and 0.2 mg citric acid as a stabilizer. Xylocaine with Epinephrine in multiple dose as an antioxidant and 0.2 mg citric acid as a stabilizer. -

Part1 Gendiff.Qxp

Sex Differences in Health Status, Health Care Use, and Quality of Care: A Population-Based Analysis for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities November 2005 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba Randy Fransoo, MSc Patricia Martens, PhD The Need to KnowTeam (funded through CIHR) Elaine Burland, MSc Heather Prior, MSc Charles Burchill, MSc Dan Chateau, PhD Randy Walld, BSc, BComm (Hons) This report is produced and published by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). It is also available in PDF format on our website at http://www.umanitoba.ca/centres/mchp/reports.htm Information concerning this report or any other report produced by MCHP can be obtained by contacting: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Dept. of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba 4th Floor, Room 408 727 McDermot Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3E 3P5 Email: [email protected] Order line: (204) 789 3805 Reception: (204) 789 3819 Fax: (204) 789 3910 How to cite this report: Fransoo R, Martens P, The Need To Know Team (funded through CIHR), Burland E, Prior H, Burchill C, Chateau D, Walld R. Sex Differences in Health Status, Health Care Use and Quality of Care: A Population-Based Analysis for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities. Winnipeg, Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, November 2005. Legal Deposit: Manitoba Legislative Library National Library of Canada ISBN 1-896489-20-6 ©Manitoba Health This report may be reproduced, in whole or in part, provided the source is cited. 1st Printing 10/27/2005 THE MANITOBA CENTRE FOR HEALTH POLICY The Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) is located within the Department of Community Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba.