NS Design CR Electric Cello Owner's Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Color in Your Own Cello! Worksheet 1

Color in your own Cello! Worksheet 1 Circle the answer! This instrument is the: Violin Viola Cello Bass Which way is this instrument played? On the shoulder On the ground Is this instrument bigger or smaller than the violin? Bigger Smaller BONUS: In the video, Will said when musicians use their fingers to pluck the strings instead of using a bow, it is called: Piano Pizazz Pizzicato Potato Worksheet 2 ALL ABOUT THE CELLO Below are a Violin, Viola, Cello, and Bass. Circle the Cello! How did you know this was the Cello? In his video, Will talked about a smooth, connected style of playing when he played the melody in The Swan. What is this style with long, flowing notes called? When musicians pluck the strings on their instrument, does it make the sounds very short or very long? What is it called when musicians pluck the strings? What does the Cello sound like to you? How does that sound make you feel? Use the back of this sheet to write or draw what the sound of the Cello makes you think of! Worksheet 1 - ANSWERS Circle the answer! This instrument is the: Violin Viola Cello Bass Which way is this instrument played? On the shoulder On the ground Is this instrument bigger or smaller than the violin? Bigger Smaller BONUS: In the video, Will said when musicians use their fingers to pluck the strings instead of using a bow, it is called: Piano Pizazz Pizzicato Potato Worksheet 2 - ANSWERS ALL ABOUT THE CELLO Below are a violin, viola, cello, and bass. -

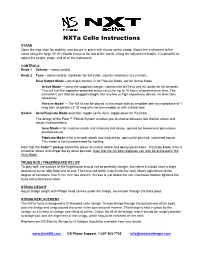

Nxta Cello Instructions STAND Open the Legs Wide for Stability, and Secure in Place with Thumb Screw Clamp

NXTa Cello Instructions STAND Open the legs wide for stability, and secure in place with thumb screw clamp. Mount the instrument to the stand using the large (5/16”) thumb screw at the top of the stand. Using the adjustment knobs, it is possible to adjust the height, angle, and tilt of the instrument. CONTROLS Knob 1 Volume – rotary control Knob 2 Tone – rotary control, clockwise for full treble, counter-clockwise to cut treble. Dual Output Mode – push-pull control, in for Passive Mode, out for Active Mode. Active Mode – Using the supplied charger, connect the NXTa to any AC outlet for 60 seconds. This will fuel the capacitor-powered active circuit for up to 16 hours of performance time. The instrument can then be plugged straight into any low or high impedance device, no direct box necessary. Passive Mode* – The NXTa can be played in this mode with an amplifier with an impedance of 1 meg ohm or greater (3-10 meg ohm recommended) or with a direct box. Switch Arco/Pizzicato Mode selection, toggle up for Arco, toggle down for Pizzicato The design of the Polar™ Pickup System enables you to choose between two distinct attack and decay characteristics: Arco Mode is for massive attack and relatively fast decay, optimal for bowed and percussive plucked sound. Pizzicato Mode is for a smooth attack and long decay, optimal for plucked, sustained sound. This mode is not recommended for bowing. Note that the Polar™ pickup allows the player to control attack and decay parameters. Pizzicato Mode is for a smoother attack and longer decay when plucked. -

The Use of Scordatura in Heinrich Biber's Harmonia Artificioso-Ariosa

RICE UNIVERSITY TUE USE OF SCORDATURA IN HEINRICH BIBER'S HARMONIA ARTIFICIOSO-ARIOSA by MARGARET KEHL MITCHELL A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE aÆMl Dr. Anne Schnoebelen, Professor of Music Chairman C<c g>'A. Dr. Paul Cooper, Professor of- Music and Composer in Ldence Professor of Music ABSTRACT The Use of Scordatura in Heinrich Biber*s Harmonia Artificioso-Ariosa by Margaret Kehl Mitchell Violin scordatura, the alteration of the normal g-d'-a'-e" tuning of the instrument, originated from the spirit of musical experimentation in the early seventeenth century. Closely tied to the construction and fittings of the baroque violin, scordatura was used to expand the technical and coloristlc resources of the instrument. Each country used scordatura within its own musical style. Al¬ though scordatura was relatively unappreciated in seventeenth-century Italy, the technique was occasionally used to aid chordal playing. Germany and Austria exploited the technical and coloristlc benefits of scordatura to produce chords, Imitative passages, and special effects. England used scordatura primarily to alter the tone color of the violin, while the technique does not appear to have been used in seventeenth- century France. Scordatura was used for possibly the most effective results in the works of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (1644-1704), a virtuoso violin¬ ist and composer. Scordatura appears in three of Biber*s works—the "Mystery Sonatas", Sonatae violino solo, and Harmonia Artificioso- Ariosa—although the technique was used for fundamentally different reasons in each set. In the "Mystery Sonatas", scordatura was used to produce various tone colors and to facilitate certain technical feats. -

Season 2012-2013

27 Season 2012-2013 Thursday, December 13, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, December 14, at 8:00 Saturday, December 15, Gianandrea Noseda Conductor at 8:00 Alisa Weilerstein Cello Borodin Overture to Prince Igor Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 I. Adagio—Moderato— II. Lento—Allegro molto III. Adagio IV. Allegro—Moderato—[Cadenza]—Allegro, ma non troppo—Poco più lento—Adagio—Allegro molto Intermission Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 29 (“Polish”) I. Introduzione ed allegro: Moderato assai (tempo di marcia funebre)—Allegro brillante II. Alla tedesca: Allegro moderato e semplice III. Andante elegiaco IV. Scherzo: Allegro vivo V. Finale: Allegro con fuoco (tempo di polacca) This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. The December 14 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and also those who enjoy the a strong partnership with The Philadelphia Orchestra’s other area the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Orchestra has cultivated performances at the Mann Festival. -

Historical Development of the Cello

Historical development of the cello The cello emerged in Italy in the mid 16th century. The chief predecessor of the modern cello was the bassa viola da braccio. The term “violoncello” was used from the mid 17th century. The earliest cellos had three strings. When four strings became used, they were initially tuned a tone lower than the present day cello (i.e. Bb, F, C and G). Occasionally, cellos were made with five strings. The violin family (including the cello but excluding the double bass) developed independently of the viol family (which flourished in the 15th to 17th centuries, until it became eclipsed by the popularity of the violin family). A consort of viols would consist of treble, tenor and bass (the latter also known as viola da gamba), although other sizes did exist (such as the contrabass, or violone). Viols are fretted, and held on or between the knees when played. They typically have six strings, with a flatter bridge than the violin’s or cello’s, making chord playing easier. Other differences, when compared with the violin family, include a flatter back, sloping shoulders, and thinner wood and strings. The bow used for the viol is slightly convex, unlike the concave bow now used by violinists and cellists. Early violin and cello makers, mostly based in northern Italy, included Giovan Giacomo Dalla Corna, Zanetto de Michelis da Montechiaro, Gasparo da Salò, Giovanni Paolo Maggini, and, most notably, Andrea Amati (c.1505-c.1576; there are surviving Amati violins dating from 1564). The tradition was continued by Andrea’s sons Antonio and Girolamo, Girolamo’s son Nicolo (1596-1684), and Nicolo’s students Andrea Guarneri and Antonio Stradivari. -

Vibration Modes of the Cello Tailpiece Eric Fouilhe, Giacomo Goli, Anne Houssay, George Stoppani

Vibration Modes of the Cello Tailpiece Eric Fouilhe, Giacomo Goli, Anne Houssay, George Stoppani To cite this version: Eric Fouilhe, Giacomo Goli, Anne Houssay, George Stoppani. Vibration Modes of the Cello Tailpiece. Archives of Acoustics, Committee on Acoustics PAS, PAS Institute of Fundamental Technological Research, Polish Acoustical Society, 2011, 36 (4), pp.713-726. 10.2478/v10168-011-0048-2. hal- 00804249 HAL Id: hal-00804249 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00804249 Submitted on 28 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License ARCHIVES OF ACOUSTICS DOI: 10.2478/v10168-011-0048-2 36, 4, 713–726 (2011) ( ) Vibration Modes of the Cello Tailpiece ∗ Eric FOUILHE(1), Giacomo GOLI(2), Anne HOUSSAY(3), George STOPPANI(4) (1)University of Montpellier 2 Laboratory of Mechanics and Civil Engineering French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) France e-mail: [email protected] (2)University of Florence Department of Economics, Engineering, Agricultural and Forestry Science and Technology (DEISTAF) Florence, Italy (3)Music Museum, City of Music Paris, France (4)Violin maker, acoustician researcher Manchester, United Kingdom (received January 16, 2011; accepted September 20, 2011) The application of modern scientific methods and measuring techniques can ex- tend the empirical knowledge used for centuries by violinmakers for making and adjusting the sound of violins, violas, and cellos. -

The Cello Bow Held the Viol

Chelys 24, article 4 [47] THE CELLO BOW HELD THE VIOL- WAY; ONCE COMMON, BUT NOW ALMOST FORGOTTEN Mark Smith Ample evidence can be found tO show that many early cellists, including some of the most distinguished, held the bow with the hand under. It seems likely that hand-under bow-holds were more cOmmon than hand-over bow- holds for cellists (at least outside of France) until about 1730, and it is certain that some important solO cellists used a hand-under bow-hold not only until 1730, but well intO the second-half of the eighteenth century. TherefOre, a significant part of the early cellO repertory (perhaps some of it well-known today) must have been first played with the hand under the bow. Until now, hand-under bow-holds have been discussed only superficially by historians of the cello.1 With more information, I hope that some cellists may try such a bow-hold in the cOmpositions which were or may have been originally played that way. Iconographic evidence Little written information about any aspect of cellO technique is known earlier than the oldest dated cellO method, that of Corrette in 1741.2 However, there are hundreds of pictures Of cellists earlier than 1741, and these provide the bulk of information about bow-holds up tO that time (see Table 1). 1 have studied 259 paintings, drawings, engravings and other works of art depicting cellists, from the earliest-known example, dating from about 1535, up tO 1800.3 The number Of depictions is probably tOO small tO give an accurate estimation of the actual number and distributiOn of cellists using the twO bow-holds. -

The Cadenza in Cello Concertos: History, Analysis, and Principles of Improvisation Boyan Bonev

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 The Cadenza in Cello Concertos: History, Analysis, and Principles of Improvisation Boyan Bonev Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE CADENZA IN CELLO CONCERTOS – HISTORY, ANALYSIS, AND PRINCIPLES OF IMPROVISATION By BOYAN BONEV A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Boyan Bonev defended on May 7, 2009. __________________________________ Gregory Sauer Professor Directing Treatise ___________________________________ Jane Piper Clendinning Outside Committee Member __________________________________ Eliot Chapo Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my major professor Gregory Sauer, and my committee members Jane Piper Clendinning and Eliot Chapo, for their help and support. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures………………………………………………………………………………... v Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………. vi INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………... 1 I. HISTORY OF CADENZAS IN CELLO CONCERTOS ………………………………..... 4 II. ANALYSIS OF AD LIBITUM CADENZAS …………………………………………….. 15 Biographical Sketch of the Authors of the Cadenzas……………………………….... 18 Analyses of Cadenzas for the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in C Major by Joseph Haydn……………………………………………………………………….... 19 Analyses of Cadenzas for the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in D Major by Joseph Haydn……………………………………………………………………….... 22 III. PRINCIPLES OF IMPROVISATION…..……………………………………………….. 30 CONCLUSION……………. ………………………………………………………………... 40 APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………………... 41 1. CADENZAS FOR THE CONCERTO FOR CELLO AND ORCHESTRA IN C MAJOR BY JOSEPH HAYDN …………………………………………………………………………… 41 2. -

In Short Tortheater in Vienna

Cello Concerto in C major, Hob. VIIb:1 Joseph Haydn t is more than a little ironic that Haydn’s deposited in the National Museum of Prague. Isplendid Cello Concerto in C major, which The parts were uncovered there by musicol- is today one his most popular concertos, lay ogist Oldřich Pulkert as recently as 1961. in oblivion for almost two centuries. Haydn In the first movement, this work unrolls at did enter it in his Entwurf-Katalog (Draft a spacious pace, without calling attention to Catalogue), an inventory he began around the considerable virtuosity required for its ex- 1765, so the piece must have been written by ecution. Pairs of oboes and horns add body to that year at the latest. This was therefore a the tutti sections, although Haydn limits the work of the composer’s first years at the Es- accompaniment to a string orchestra when terházy Court, which makes sense given the the cello is playing. The wisdom of his deci- prominent solo-cello writing he employed sion to keep the textures light is confirmed in some of his other pieces of that time; the by later cello concertos (by other composers) well-known Symphonies Nos. 6–8 come im- in which the soloist can be seen playing but mediately to mind, as well as the Sympho- can scarcely be heard. Of course, problems nies Nos. 13, 31, 36, and 72 — all, despite their of balance between soloist and orchestra are eventual numbering, from 1765 or earlier. considerably reduced when the “symphonic” The cellist all these works were meant to forces are hardly larger than a chamber group spotlight was Joseph Franz Weigl, one of — as they were when this piece was new.