The Cadenza in Cello Concertos: History, Analysis, and Principles of Improvisation Boyan Bonev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Totalartwork

spınetL an Experiment on Gesamtkunstwerk Totalartwork Thursday–Friday October 21–22, 2004 The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art www.birgitramsauer.net/spinet 21 October 22 October Panel Discussion 6–7pm Panel Discussion 6–7pm Contemporary artists and an The Gesamtkunstwerk (Totalartwork) historical instrument in the 21st century Moderator: Moderator: Christopher McIntyre Christopher McIntyre Associate Music Curator, The Kitchen Associate Music Curator, The Kitchen Participants include: Jens Barnieck, pianist Participants include: Enrico Cocco, composer Jens Barnieck, pianist Gearoid Dolan, artist Enrico Cocco, composer Kyle Gann, composer, critic Gearoid Dolan, artist Thea Herold, word performer Thea Herold, word performer Charlie Morrow, composer Charlie Morrow, composer Aloisia Moser, philosopher Wolf-Dieter Neupert, company Wolf-Dieter Neupert, company for historical instruments for historical instruments Georg Nussbaumer, composer Georg Nussbaumer, composer Birgit Ramsauer, artist Birgit Ramsauer, artist Kartharina Rosenberger, Katharina Rosenberger, composer composer David Grahame Shane, architect, urbanist, author Concert 8pm Gerd Stern, poet and artist Gloria Coates Abraham Lincoln’s Performance 8pm Cooper Union Address* Frieder Butzmann Stefano Giannotti Soirée pour double solitaires * L’Arte des Paesaggio Charlie Morrow, alive I was silent Horst Lohse, Birgit’s Toy* and in death I do sing* Intermission Enrico Cocco, The Scene of Crime* Heinrich Hartl, Cemballissimo Aldo Brizzi, The Rosa Shocking* Katharina Rosenberger, -

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: the Success of Arthur Honeggerâ•Žs Antigone in Vichy France

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 7 2021 Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France Emma K. Schubart University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Schubart, Emma K. (2021) "Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 7 MUSICAL HYBRIDIZATION AND POLITICAL CONTRADICTION: THE SUCCESS OF ARTHUR HONEGGER’S ANTIGONE IN VICHY FRANCE EMMA K. SCHUBART, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL MENTOR: SHARON JAMES Abstract Arthur Honegger’s modernist opera Antigone appeared at the Paris Opéra in 1943, sixteen years after its unremarkable premiere in Brussels. The sudden Parisian success of the opera was extraordinary: the work was enthusiastically received by the French public, the Vichy collaborationist authorities, and the occupying Nazi officials. The improbable wartime triumph of Antigone can be explained by a unique confluence of compositional, political, and cultural realities. Honegger’s compositional hybridization of French and German musical traditions, as well as his opportunistic commercial motivations as a Swiss composer working in German-occupied France, certainly aided the success of the opera. -

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Techniques in David Popper's Hohe Schule Des Violoncello-Spiels, Op. 73

Conservatorium of Music Techniques in David Popper's Hohe Schule des Violoncello-Spiels, op. 73 by Felicity Allan-Eames Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Music (Honours) University of Tasmania (June, 2013) DECLARATION I declare that all material in this exegesis is my own work except where there is clear acknowledgement or reference to the work of others and I have read the University statement on Academic misconduct (Plagia rism) on the University website at www.utas.edu.au/plagiarism or in the Student Information Handbook. I further declare that no part of this pa per has been submitted for assessment in any other unit at this university or any other institution. I consent the authority of access to copying this exegesis. This authority is subject to any agreement entered into by the University concerning access to the exegesis. Felicity Allan-Eames 6th June 2013 ABSTRACT Virtuoso cellist, pedagogue and composer, David Popper was an instru mental figure in the development of cello technique in the late nine teenth and early twentieth centuries. Popper's technical principles and innovations are laid down in his monumental work the Hohe Schule des Violoncello-Spiels. Certainly his greatest contribution, these forty im mensely challenging and musically-rewarding etudes are now studied all over the world. A thorough understanding of the many techniques re quired in these etudes, as well as effective practice methods, are cru cial for a cellist's development of technical skills. These techniques and practice methods have been somewhat overlooked in the available liter ature. -

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Announces 2019 New Music Festival

Media contacts Linda Moxley, VP of Marketing & Communications 410.783.8020 [email protected] Devon Maloney, Director of Communications 410.783.8071 [email protected] For Immediate Release Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Announces 2019 New Music Festival Baltimore (April 18, 2019) Under the leadership of Music Director Marin Alsop, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) announces the 2019 New Music Festival. Launched by Alsop and the BSO in 2017, the New Music Festival brings contemporary classical music to Baltimore from June 19-22. The 2019 New Music Festival celebrates women composers ahead of the BSO’s 2019-20 season, which highlights women in music in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the U.S. Performances include the Baltimore premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s Low Brass Concerto, a BSO co- commission, as well as the world premiere of Anna Clyne’s cello concerto, Dance, with Inbal Segev. “I’m thrilled that this year’s New Music Festival features such an outstanding group of contemporary composers, who happen to be women!” said Alsop. “Each piece of music that we’ve programmed tells a unique and compelling story, and we are proud to present a range of voices and perspectives that showcases some of the most inspired work happening in classical composition today.” The 2019 New Music Festival kicks off on Wednesday, June 19 when composer Sarah Kirkland Snider participates in a discussion on her composition process at Red Emma’s Bookstore Café. On Thursday, June 20, Associate Conductor Nicholas Hersh leads members of the BSO and Shara Nova, also known as My Brightest Diamond, in a free concert at the Ottobar. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

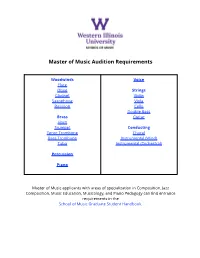

Audition Requirements

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op.