Digging Below the Water: a Bibliographical Essay on Life Before the Quabbin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of Quabbin Reservoir

International Symposium on Technology and Society Jun 1st, 4:10 PM - 4:20 PM Session 7 - Technology and the creation of wilderness: The Making of quabbin reservoir Timothy J. Farnham University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/iste Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Fresh Water Studies Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Place and Environment Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Repository Citation Farnham, Timothy J., "Session 7 - Technology and the creation of wilderness: The Making of quabbin reservoir" (2007). International Symposium on Technology and Society. 25. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/iste/2007/june1/25 This Event is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Event in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Event has been accepted for inclusion in International Symposium on Technology and Society by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Technology and the Creation of Wilderness: The Making of Quabbin Reservoir Timothy J. Farnham Department of Environmental Studies University of Nevada, Las Vegas [email protected] Abstract symbols of human domination that offend aesthetic and ethical sensibilities. -

2018 Water System Master Plan

MWRA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Matthew A. Beaton, Chairman John J. Carroll, Vice-Chair Christopher Cook Joseph C. Foti Kevin L. Cotter Paul E. Flanagan Andrew M. Pappastergion, Secretary Brian Peña Henry F. Vitale John J. Walsh Jennifer L. Wolowicz Prepared under the direction of Frederick A. Laskey, Executive Director David W. Coppes, Chief Operating Officer Stephen A. Estes-Smargiassi, Director, Planning and Sustainability Lisa M. Marx, Senior Program Manager, Planning Carl H. Leone, Senior Program Manager, Planning together with the participation of MWRA staff 2018 MWRA Water System Master Plan Table of Contents Executive Summary Chapter 1-Introduction 1.1 Overview of MWRA 1-1 1.2 Purpose of the Water Master Plan 1-1 1.3 Planning Approach, Assumptions and Time Frame 1-2 1.4 Organization of the Master Plan 1-3 1.5 Periodic Updates 1-3 1.6 MWRA Business Plan 1-3 1.7 Project Prioritization 1-4 Chapter 2-Planning Goals and Objectives 2.1 Planning Goals and Objectives Defining MWRA’S Water System Mission 2-1 2.2 Provide Reliable Water Delivery 2-2 2.3 Deliver High Quality Water 2-3 2.4 Assure an Adequate Supply of Water 2-4 2.5 Manage the System Efficiently and Effectively 2-5 Chapter 3-Water System History, Organization and Key Infrastructure 3.1 The Beginning – The Water System 3-1 3.2 The MWRA Water System Today 3-5 3.3 Water Infrastructure Replacement Asset Value 3-8 3.4 The Future Years 3-11 Chapter 4-Supply and Demand 4.1 Overview of the Water Supply System 4-1 4.2 System Capacity 4-4 4.3 Potential Impacts of Climate Change 4-6 4.4 Current -

Landmarks Preservation Commission 2007, Designation List 397 LP- 2231 GILLETT-TYLER HOUSE, 103 Circle Road, A.K.A. 103 the Circl

Landmarks Preservation Commission 2007, Designation List 397 LP- 2231 GILLETT-TYLER HOUSE, 103 Circle Road, a.k.a. 103 The Circle, Staten Island. Built c.1846, Re-constructed 1931, Additions 1932 and 1986-93. Landmark Site: Borough of Staten Island Tax Map Block 866, Lot 377 (Tentative Lot 377, approved April 4, 2007) On April 10, 2007, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Gillett-Tyler House, 103 Circle Road, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 9). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Six speakers including a representative of the owner of the building and representatives of the Preservation League of Staten Island, Historic Districts Council, the Municipal Arts Society, the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America, and the West Brighton Restoration Society testified in favor of the designation. There were no speakers in opposition to the designation. The Commission has received a letter in support of the designation from the Rego-Forest Preservation Council. Summary The Gillett-Tyler house is significant for its architectural design, for its association with an important period of American history, and for its association with three significant persons. Picturesquely sited on Todt Hill, this impressive Greek-Revival-style mansion is a fine example of the early-nineteenth-century frame buildings that were constructed in New York, New England and throughout the country. Originally built in Enfield, Massachusetts around 1846 for Daniel B. Gillett, this two-story house was reconstructed in Staten Island in 1931, when the buildings in the Swift River Valley were moved or razed to allow for the creation of the Quabbin Reservoir in western Massachusetts. -

2010 Ware River Watershed Access Plan

Public Access Management Plan Update – 2010 Ware River Watershed December 2009 Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Water Supply Protection Office of Watershed Management Abstract The Public Access Management Plan Update 2010 - Ware River Watershed explains DCR- Watershed’s obligation to manage public access on its drinking water supply lands, the process used in developing the management plan, and its policies. The update process included an intensive public input component which collected survey data from 274 stakeholders from a period of May 2009-September 2009. This management plan contains six sections 1) an introduction to DCR-Watershed, with a revised Master Policy statement ; 2) a brief history of the Ware River Watershed and existing conditions; 3) the methodology used in the update and development of the policies in the plan; 4) Fact Sheets, with maps where appropriate, for 29 individual public access policies; 5) the description of related operational activities; and 6) an Implementation Schedule, including a new annual policy review process. The revisions and updates made to the 2010 plan have clarified existing policies. Eight policies were modified and one policy was added. DCR will begin implementation of the Public Access Management Plan Update starting January 2010. DCR will conduct an annual report to evaluate the Plan in general, as well as any policy concerns or conflicts that arose during the year beginning with its first report in 2011. DCR-Watershed intends to conduct another Plan update by 2020, or earlier, if needed. Citation Public Access Management Plan Update 2010 - Ware River Watershed. Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Water Supply Protection, Belchertown, MA. -

5-17Uqentire.Pdf

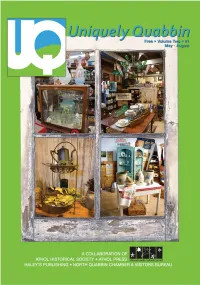

Uniquely Quabbin magazine serving THE NORTH QUABBIN: Athol • Erving • New Salem • Orange • Petersham • Phillipston • Royalston • Templeton • Warwick • Wendell THE SOUTH QUABBIN: Barre • Belchertown • Hardwick (Gilbertville) • Hubbardston • Leverett • New Braintree • Oakham • Pelham • Rutland • Shutesbury • Ware CONTENTS volume 2, number 1 • May-August 2017 this issue features antique shops, consignment stores, history, events, and sights to see in the uniquely Quabbin heart of Massachusetts the importance of bees . 5 Quabbin water levels . 6 what happens to water . 8 Boy Scout and YMCA camps . 11 Quabbin region farmers markets . 12 “Come fly with me!” . 16 Quabbin Reservation tracker . 18 (continued on page 2) Like other Quabbin region shops, fairs, flea markets, and auctions, SteepleAntiques in Templeton, upper left, highlights yesteryear. maps, bottom, show Quabbin towns past and present • photo © David Brothers / maps © Casey Williams MAY-AUGUST 2017 • UNIQUELY QUABBIN MAGAZINE 1 CONTENTS a note of thanks from Athol Historical Society (continued from Page 1) Dear local cultural councils of the Quabbin region, On behalf of Athol Historical Society, thank you for hat-making flourished . 22 funding Uniquely Quabbin magazine. Quabbin region eateries . 26 In addition to generous individual donors who supported our winter fundraisers, we want to thank Athol Nature’s Nuances . 27 Cultural Council, Erving Cultural Council, Hubbardston vineyards and wineries . 28 Cultural Council, New Salem Cultural Council, Oakham Cultural Council, and Orange Cultural Council. discovering consignment shops . 30 Also, Pelham Cultural Council, Petersham Cultural Council, Phillipston Cultural Council, Royalston Cultural haunts for antique hounds . 32 Council, Ware Cultural Council, Warwick Cultural everything old is new again . 36 Council, and Wendell Cultural Council. -

Spencer Family Dental

SPENCER FAMILY DENTAL GUZIK MOTOR SALES For CELEBRATING OUR 50TH Anniversary as a Family Owned Business! Gentle Caring State of the Art Dentistry For The Whole Family Cosmetic Dentistry • Restorative Dentistry • Preventative Dentistry CROWNS • CAPS • BRIDGES • COMPLETE and PARTIAL DENTURES Best Deals of The Year advertising New We Strive NON SURGICAL GUM TREATMENT • ROOT CANAL THERAPY on 2012 Jeeps! Patients SURGICAL SERVICES For Painless information Welcome BREATH CLINIC-WE TREAT CHRONIC BAD BREATH Dentistry HERBAL DENTAL PRODUCTS • All Instruments Fully Sterilized • Most Insurances Accepted Never a Document Fee 2012 Never A Dealer Prep Fee Jeep call June Dr. Nasser S. Hanna Liberty Never An Interest Rate Mark Up Conveniently Located On Route 9 • (Corner of Greenville St. & Main St.) PLUS 5 year / 100,000 mile powertrain warranty today, 284 Main St., Spencer 508-885-5511 PLUS interest rates at historic lows 1941-2011 (509)909-4062 E. Main St., Rtes. 9 & 32, Ware Just Over the West Brookfield Line TheHeartOfMassachusetts.com 413-967-4210 or 800-793-2078 • www.guzikmotors.com Mailed free to requesting homes in East Brookfield, West Brookfield, North Brookfield, Brookfield, Leicester and Spencer Vol. XXXV, No. 47 PROUD MEDIA SPONSOR OF RELAY FOR LIFE OF THE GREATER SOUTHBRIDGE AREA! Complimentary to homes by request ONLINE: WWW.SPENCERNEWLEADER.COM Friday, November 23, 2012 THIS WEEK’S QUOTE ‘O little town of North Brookfield’ Third-largest “It is better to look ahead and prepare ‘solar farm’ in than to look back and regret.” Mass. eyed Jackie Joyner-Kersee INSIDE for Spencer BY ELISA KROCHMALNYCKYJ farm in the state, officials Obituaries ....B Section NEW LEADER CORRESPONDENT said. -

Table of Contents

HARDWICK, MASSACHUSETTS OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN PREPARED BY THE HARDWICK MASTER PLAN COMMITTEE APRIL, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Plan Summary........................................................................................................................... 1 B. Introduction............................................................................................................................... 3 B1. Statement of Purpose ....................................................................................................................3 B2. Planning Process and Public Participation....................................................................................3 C. Community Setting................................................................................................................... 5 C1. Regional Context ..........................................................................................................................5 C2. History of the Community ............................................................................................................6 C3. Population Characteristics.............................................................................................................8 Environmental Justice Neighborhoods.......................................................................................13 C4. Growth and Development Patterns .............................................................................................13 Patterns and Trends ....................................................................................................................13 -

Annual Report of the Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission

Public Document No» 147 ^ASS. ©I|^ (Unmmnnmtultli nf MtxmutiinstttB DOCS. :OLL. ! ANNUAL REPORT OF THE METROPOLITAN DISTRICT WATER SUPPLY COMMISSION FOR THE Year Ending November 30, 1938 Publication of this Document Approved by the Commission on Administration and Finance Im-l-MO. D-1S23. REPORT OF THE METROPOLITAN DISTRICT WATER SUPPLY COMMISSION To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives of the Common- zuealth of Massachusetts in General Court Assembled. The Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission, established under the provisions of Chapter 375 of the Acts of 1926, respectfully presents for the year ending November 30, 1938 its THIRTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT I. Organization and Administration Eugene C. Hultman continued as Chairman of the Commission and Thomas D. Lavelle and Edward J. Kelley as Associate Commissioners. R. Nelson Molt continued as Secretary. During the past year the Administrative functions of the Commission have been greatly increased by new construction work authorized by Chapter 460 as amended by Chapter 501 of the Acts of 1938. This new construction was made possible because of the saving by the Com- mission estimated from $12,000,000.00 to $14,0000,000.00 from the appropriation of $65,000,000.00 authorized in 1926 and 1927 by the Legislature and these Acts were passed after consideration of the special report which, prepared under Chapter 48, Resolves of 1936, by a joint board consisting of this Commis- sion and the Department of Public Health relative to improvements in distribu- tion and to adequate prevention of pollution of sources of water supply of the Metropolitan water district and printed as House document No. -

Long-Range Water Supply Planning

, , ' ;, ,,'" ~i~ ~ ~I :~ . '\ -' -.- ',.,.'" -.."..~ .-. ~ ::-- -.'\ i" \ CaseAnalysis . ~ . .. Long-Range Surface Water Supply Planning consideredto representthe "safe yield" from . .. the Quabbin and WachusettReservoirs, the Recent projections Indicate that principalsources of supply. eastern Massachusetts must Aftera droughtthat occurredduring the expand its surface water supply mid-1960sthat se~~edas a warnin? to the . area water authorItIes, several studies were system to deuver an adequate undertaken.In 1969,the U.S.Army Corpsof supply during the coming Engineersestimated a potentialshortage of decades. Understanding the up to 140 mgd in the MDC/MWRA supply . area by 1990} In 1977,the now defunct New relatIonships among system EnglandRiver Basin Commission projected storage,reliability and yield is a shortageof 77 mgd by 1990.3In 1978,the essential to the solution of this MassachusettsExecutive Office of Environ- . mental Affairs estimated a shortfall of 70 long-range plannIng problem. mgd by 1990 for communities serviced by the MDC/MWRA.4A current study by the RICHARDM. VOGEL& DAVIDI. HELLSTROM MDC/MWRA, initiated in 1981, projects a shortfall of approximately 120 mgd by the A REPORTdeveloped by the Metro- year 2020.1 politan District Commission(MDC) A principal ingredient of the MDC/MWRA and the Massachusetts Water study was to determinethe "safe yield" that ResourceAuthority (MWRA)entitled, "Water the water supply system can deliver until Supply Study and Environmental Impact the year 2020.The choice of water sources Report," describes an enormous project to augmentthe existingwater supply system which, if and when completed, will identify depends primarily on the knowledge of the the preferred alternative(s) for meeting the "safe yield" of both the existing system and projected water supply needs of the areas the sourcesunder consideration,in addition . -

How Do They Mow That Slope?

Quabbin Voices The Friends of Quabbin Newsletter How Do They Mow that Slope? Edited by Paul Godfrey from an article in “Downstream,” a DCR biannual newsletter, by Scott Campbell, DCR Regional Engineer at Quabbin Reservoir supplemented by additional information from Nancy Huntington, DCR Visitor Services Supervisors Summer 2015 Vol.28 No.2 Winsor Dam and the Goodnough Dike, con- visual inspections of slope and ground condi- structed between 1933 and 1939, are two tions. It may also provide habitat and shelter- earthen dam structures that together impound ing for burrowing animals. If left unchecked We must hear and listen about 412 billion gallons of water from the and uncontrolled, deep penetrations from to all of Quabbin’s many Swift River Valley and Ware River Diversion. roots of woody vegetation or burrowing Voices. Voices of the Past, Winsor Dam, the larger of the two structures, animals could penetrate and structurally as well as Voices of the spans 2,640 feet in length and rises 17 0 feet compromise components of the dam. Mowing Present and of the Future. above the original bed of the Swift Riv er. and other vegetation management efforts are Voices of the Trees, the Goodnough Dike is only slightly smaller, span- critical components of the dam maintenance Sky, the Rain that falls, ning 2,140 feet and rising 135 feet abo ve the and inspection programs that DCR implements and all the Wild Things; original bed of Beaver Brook. Combined, the to ensure the safety and long-term dependabil- two structures contain more than 55 acres of ity of the infrastructure holding back billions of Voices of the People who grassed landscape areas, roughly eight acres gallons of drinking water. -

Metropolitan District Commission Water Supply Study and Environmental Impact Report-2020

Metropolitan District Commission Water Supply Study and Environmental Impact Report-2020 TASK 18.20: A HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE METROPOLITAN DISTRICT COMMISSION WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM Submitted to: Metropolitan District Commission Prepared by: Wallace, Floyd, Associates Inc. September, 1984 Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 Boston's Early Water Supply 4 The Metropolitan Water District 5 The 1895 Board of Health Study ~ 6 Population Projections 1895-1930 7 Water Demand Projections 1895-1930 10 Unaccounted-for Water and Leakage 11 Alternative Water Supply Sources 14 The Establishment of the Metropolitan District Commission 15 The 1922 Joint Board Study 16 Population Projections 1920-1970 18 Water Demand Projections 1920-1970 20 Conservation and Demand Management 21 Alternative Water Supply Sources 23 Recommendations of the Joint Board 23 The Minority Report 26 Comparison of Historic Trends with the Water Supply Study and EIR-2020. List of Tables Tables Page Table 1 4 Chronology of Development of Boston and MDC Water Supply Sources Table 2 9 Water Consumption, 1895-1930 Table 3 10 Breakdown of Water Use by Sector, 1895 and 1980 Table 4 12 1985 Evaluation of Water Supply Alternatives Table 5 13 Cost of Reservoir Storage Table 6 16 MDC Population, Projected and Actual, 1920- 1970 Table 7 17 Chronology of Growth of MDC Service Area Table 8 19 Comparison of Water Use Growth Rates List of Figures Figures Page Figure 1 3 Boston/MDC Cumulative Reservoir Storage Capacity Figure 2 7 MDC Population and Projections 1895-1930 and 1925-1970 Figure 3 8 Boston/Metropolitan Water District Per Capita Water Consumption Figure 4 9 Historic and Projected MDC Service Population, 1850-2020 Figure 5 18 Boston/MDC Water Use and Projections 1850- 2020 INTRODUTCTION Boston, one of the oldest cities in the United States, has one of the oldest public water supply systems, dating back to 1652. -

Barre Open Space and Recreation Plan

Barre Open Space and Recreation Plan Barre, Massachusetts September 2010 With Assistance from 2 2 Washington Square Union Station Worcester, MA 01604 www.cmrpc.org Approval granted through October 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 ‐ PLAN SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 1 SECTION 2 – INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 3 A ‐ Statement of Purpose ............................................................................................................ 3 B ‐ Planning Process and Public Participation ............................................................................. 4 SECTION 3 ‐ COMMUNITY SETTING ............................................................................................... 7 A ‐ Regional Context .................................................................................................................... 7 B ‐ History of Community ............................................................................................................ 8 C ‐ Population Characteristics .................................................................................................... 11 D ‐ Growth and Development Patterns ..................................................................................... 15 SECTION 4 ‐ ENVIRONMENTAL INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS ...................................................... 23 A ‐ Geology, Soils, and Topography ..........................................................................................