Beach Vitex (Vitex Rotundifolia): an Invasive Coastal Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex Rotundifolia L. F. (Lamiaceae)

Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex United States rotundifolia L. f. (Lamiaceae) – Beach Department of Agriculture vitex Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service June 4, 2013 Version 2 Left: Infestation in South Carolina growing down to water line and with runners and fruit stripped by major winter storm (Randy Westbrooks, U.S. Geological Survey, Bugwood.org). Right: A runner with flowering shoots (Forest and Kim Starr, Starr Environmental, Bugwood.org). Agency Contact: Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory Center for Plant Health Science and Technology Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service United States Department of Agriculture 1730 Varsity Drive, Suite 300 Raleigh, NC 27606 Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex rotundifolia Introduction Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ) regulates noxious weeds under the authority of the Plant Protection Act (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000) and the Federal Seed Act (7 U.S.C. § 1581-1610, 1939). A noxious weed is defined as “any plant or plant product that can directly or indirectly injure or cause damage to crops (including nursery stock or plant products), livestock, poultry, or other interests of agriculture, irrigation, navigation, the natural resources of the United States, the public health, or the environment” (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000). We use weed risk assessment (WRA)—specifically, the PPQ WRA model (Koop et al., 2012)—to evaluate the risk potential of plants, including those newly detected in the United States, those proposed for import, and those emerging as weeds elsewhere in the world. Because the PPQ WRA model is geographically and climatically neutral, it can be used to evaluate the baseline invasive/weed potential of any plant species for the entire United States or for any area within it. -

Estrogen-Like Activities in Vitex Species from China Determined by a Cell Based Proliferation Assay

ORIGINAL ARTICLES Department of Pharmacognosy1, School of Pharmacy, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China; School of Biomo- lecular Science2, Faculty of Sciences, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK Estrogen-like activities in Vitex species from China determined by a cell based proliferation assay Y. Hu1, Q.-Y. Zhang1, T.-T. Hou1, H.-L. Xin1, H.-C. Zheng1, K. Rahman2, L.-P. Qin1 Received February 14, 2007, accepted March 29, 2007 Prof. Lu-Ping Qin, Departement of Pharmacognosy, School of Pharmacy, Second Military Medical Uni- versity, 325 Guohe Road, Shanghai 200433, China [email protected], [email protected] Pharmazie 62: 872–875 (2007) doi: 10.1691/ph.2007.11.7542 Ethanolic extracts of four Chinese medicinally used Vitex species were selected and tested for their estrogen-like activities, using an ERa-positive MCF-7 cell based proliferation assay (E-screen assay) and cell cycle analysis (flow cytometry). Vitex negundo displayed the highest estrogenic-like activity, and could be useful in hormone replacement therapy (HRT). 1. Introduction 2. Investigations, result and discussion Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds with estro- In the E-Screen assay using MCF-7 cells, the proliferative genic or antiestrogenic properties (Umland et al. 2000). effect of the extracts relative to that of estradiol (1 nM, They seem to be interesting by their possible use as al- 100%) is expressed as Relative Proliferative Effect (RPE) ternative medicines for treating hormonal disorders such (Fig. 1). The results clearly indicate that the extracts from as in hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Thus, phy- V. rotundifolia and V. negundo were able to significantly toestrogens could be beneficial in treatment of the symp- stimulate MCF-7 cell proliferation at concentrations of toms of menopause and hence help to prevent bone re- 50 mg/mL to100 mg/mL (P < 0.01). -

Vitex Agnus-Castus Extracts for Female Reproductive Disorders: a Systematic Review of Clinical Trials

562 Reviews Vitex agnus-castus Extracts for Female Reproductive Disorders: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials Authors M. Diana van Die1, Henry G. Burger2, Helena J. Teede3, Kerry M. Bone 4 Affiliations 1 Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology-University, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia 2 Prince Henryʼs Institute of Medical Research, Clayton, Victoria, Australia 3 Monash University, Clayton; Southern Health, Dandenong, Victoria, Australia 4 University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales; MediHerb/Integria, Warwick, Queensland, Australia Key words Abstract (1), and magnesium oxide (1). In premenstrual l" Vitex agnus‑castus ! dysphoric disorder, one study reported Vitex to l" Verbenaceae Vitex agnus-castus L. (chaste tree; chasteberry) is be equivalent to fluoxetine, while in the other, l" premenstrual a popular herbal treatment, predominantly used fluoxetine outperformed Vitex. In latent hyper- l" mastalgia for a range of female reproductive conditions in prolactinaemia, one trial reported it to be superi- l" hyperprolactinaemia l" systematic review Anglo-American and European practice. The ob- or to placebo for reducing TRH-stimulated prolac- jective of this systematic review was to evaluate tin secretion, normalising a shortened luteal the evidence for the efficacy and safety of Vitex phase, increasing mid-luteal progesterone and extracts from randomised, controlled trials inves- 17β-oestradiol levels, while the other found Vitex tigating womenʼs health. comparable to bromocriptine for reducing serum Eight databases were searched using Latin and prolactin levels and ameliorating cyclic mastalgia. common names for Vitex and phytotherapeutic Adverse events with Vitex were mild and gener- preparations of the herb as a sole agent, together ally infrequent. The methodological quality of with filters for randomised, controlled trials or the included studies varied, but was generally clinical trials. -

Vitex Rotundifolia L.F

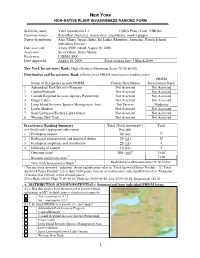

NEW YORK NON -NATIVE PLANT INVASIVENESS RANKING FORM Scientific name: Vitex rotundifolia L.f. USDA Plants Code: VIRO80 Common names: Roundleaf chastetree, beach vitex, chasteberry, monk's pepper Native distribution: Asia (China, Japan), India, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Australia, Pacific Islands (inlcuding Hawaii) Date assessed: 3 June 2009; edited August 19, 2009 Assessors: Steve Glenn, Gerry Moore Reviewers: LIISMA SRC Date Approved: August 19, 2009 Form version date: 3 March 2009 New York Invasiveness Rank: High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) Distribution and Invasiveness Rank ( Obtain from PRISM invasiveness ranking form ) PRISM Status of this species in each PRISM: Current Distribution Invasiveness Rank 1 Adirondack Park Invasive Program Not Assessed Not Assessed 2 Capital/Mohawk Not Assessed Not Assessed 3 Catskill Regional Invasive Species Partnership Not Assessed Not Assessed 4 Finger Lakes Not Assessed Not Assessed 5 Long Island Invasive Species Management Area Not Present Moderate 6 Lower Hudson Not Assessed Not Assessed 7 Saint Lawrence/Eastern Lake Ontario Not Assessed Not Assessed 8 Western New York Not Assessed Not Assessed Invasiveness Ranking Summary Total (Total Answered*) Total (see details under appropriate sub-section) Possible 1 Ecological impact 40 ( 40 ) 37 2 Biological characteristic and dispersal ability 25 ( 25 ) 20 3 Ecological amplitude and distribution 25 ( 25 ) 4 4 Difficulty of control 10 ( 10 ) 8 Outcome score 100 ( 100 )b 73.00 a † Relative maximum score 73.00 § New York Invasiveness Rank High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) * For questions answered “unknown” do not include point value in “Total Answered Points Possible.” If “Total Answered Points Possible” is less than 70.00 points, then the overall invasive rank should be listed as “Unknown.” †Calculated as 100(a/b) to two decimal places. -

(Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae) Using Two DNA Barcode Markers

J Biosci (2020)45:96 Ó Indian Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1007/s12038-020-00061-2 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) Re-evaluation of the phylogenetic relationships and species delimitation of two closely related families (Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae) using two DNA barcode markers 1 2 3 OOOYEBANJI *, E C CHUKWUMA ,KABOLARINWA , 4 5 6 OIADEJOBI ,SBADEYEMI and A O AYOOLA 1Department of Botany, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria 2Forest Herbarium Ibadan (FHI), Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria, Ibadan, Nigeria 3Department of Education Science (Biology Unit), Distance Learning Institute, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria 4Landmark University, Omu-Aran, Kwara State, Nigeria 5Ethnobotany Unit, Department of Plant Biology, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria 6Department of Ecotourism and Wildlife Management, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria *Corresponding author (Email, [email protected]) MS received 21 September 2019; accepted 27 May 2020 The families Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae comprise several closely related species that possess high mor- phological synapomorphic traits. Hence, there is a tendency of species misidentification using only the mor- phological characters. Herein, we evaluated the discriminatory power of the universal DNA barcodes (matK and rbcL) for 53 species spanning the two families. Using these markers, we inferred phylogenetic relation- ships and conducted species delimitation analysis using four delimitation methods: Automated Barcode Gap Discovery (ABGD), TaxonDNA, Bayesian Poisson Tree Processes (bPTP) and General Mixed Yule Coalescent (GMYC). The phylogenetic reconstruction based on the matK gene resolved the relationships between the families and further suggested the expansion of the Lamiaceae to include some core Verbanaceae genus, e.g., Gmelina. -

NVEO 2017, Volume 4, Issue 4, Pages 14-27

Nat. Volatiles & Essent. Oils, 2017: 4(4): 14-27 Celep & Dirmenci REVIEW Systematic and Biogeographic overview of Lamiaceae in Turkey Ferhat Celep1,* and Tuncay Dirmenci2 1 Mehmet Akif Ersoy mah. 269. cad. Urankent Prestij Konutları, C16 Blok, No: 53, Demetevler, Ankara, TURKEY 2 Biology Education, Necatibey Education Faculty, Balıkesir University, Balıkesir, TURKEY *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Lamiaceae is the third largest family based on the taxon number and fourth largest family based on the species number in Turkey. The family has 48 genera and 782 taxa (603 species, 179 subspecies and varieties), 346 taxa (271 species, 75 subspecies and varieties) of which are endemic (ca. 44%) (data updated 1th February 2017) in the country. There are also 23 hybrid species, 19 of which are endemic (82%). The results proven that Turkey is one of the centers of diversity for Lamiaceae in the Old World. In addition, Turkey has about 10% of all Lamiaceae members in the World. The largest five genera in the country based on the taxon number are Stachys (118 taxa), Salvia (107 taxa), Sideritis (54 taxa), Phlomis (53 taxa) and Teucrium (49 taxa). According to taxon number, five genera with the highest endemism ratio are Dorystaechas (1 taxon, 100%), Lophantus (1 taxon, 100%), Sideritis (54 taxa, 74%), Drymosiphon (9 taxa, 67%), and Marrubium (27 taxa, 63%). There are two monotypic genera in Turkey as Dorystaechas and Pentapleura. Turkey sits on the junction of three phytogeographic regions with highly diverse climate and the other ecologic features. Phytogeographic distribution of Turkish Lamiaceae taxa are 293 taxa in the Mediterranean (37.4%), 267 taxa in the Irano-Turanian (36.7%), 90 taxa in the Euro-Siberian (Circumboreal) phytogeographic region, and 112 taxa in Unknown or Multiregional (14.3%) phytogeographical elements. -

A Taxonomic Revision of the Genus Vi7ex L

J. Adelaide Sot. Gard. 10(1): 31-79(1987) A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE GENUS VI7EX L. (VERBENACEAE)* IN AUSTRALIA Ahmad Abid Munir State Herbarium, Botanic Gardens, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000 Abstract A taxonomic revision of Vitex in Australia is presented. The following eight species are recognised: V. acuminata, V. bentlzamiana, V. glabrata, V. helogiton, V. melicopea, V. rotundifolia, V. trifolia and V. velutinifolia. V. velutinifolia (from Western Australia) is described as new. V. melicopea and V. helogiton are reinstated, with V. helogiton being recorded from Australia for the first time. V. rotundifolia is reinstated as the oldest valid name for the 1-foliolate species previously often named V. ovata, V. tnfolia var. ovata, V. &Oita var. unifoliolata, V. trifolia var. simplicifolia or V. trtfolia subsp. littoralis. V. tnfolia var, bicolor is placed in synonymy of V. trifolia var. trifolia. The following four species are typified: V. acuminata, V. benthamiana, V. helogiton and V. melicopea. A mnge of material of the non- endemic species was examined from Malesia. Affinities and distribution are considered for each species. A key to the species is provided and a detailed description of each species is supplemented by a habit sketch of a flowering branch and analytical drawings of the flower. Taxonomic History of the Genus The genus Vitex was described by Linnaeus (1753) with four species, V. agnus-castus, V trifolio, V. negundo and V. pinnata. The syntypes of the first named species came from Sicily and Naples, the second and third from India, and the fourth type from Ceylon. The genus was placed together with Clerodendrum, Gmelina and a few other genera of present Verbenaceae in "Didynamia Angiospermia", where it was retained by Murray (1774), Reichard (1778), Loureiro (1793), Schreber (1791), Gmelin (1792), Persoon (1797, 1807), Willdenow (1800), Link (1822), Lamarck & Poiret (1823), Sprengel (1825), Roxburgh (1832), Dietrich (1842) and a few others. -

Preference and Suitability of Nigerian Grown Gmelina Arborea Linn. Roxb

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 5, May-2014 1484 ISSN 2229-5518 Preference and Suitability of Nigerian Grown Gmelina arborea Linn. Roxb. and Vitex doniana Sweet Woods for Beekeeping in Imeko, Nigeria Adedeji, G. A. and A.A. Aiyeloja. Abstract It has been observed that Apis mellifera native to tropical Africa has special preferential nesting behaviour for white and yellow woods’ cavities in Nigeria. In contrast, the use of brown coloured wood like Milicia excelsa for beekeeping on the ground of its durability has been recommended in Ghana. In response to this, the study investigated the suitability of one exotic white coloured wood species (Gmelina arborea), one indigenous white coloured wood species (Vitex doniana) and one indigenous brown coloured wood species (Erythrophleum suaveolens) for beekeeping in Imeko between February, 2009 and April, 2012. A total of 9 hives comprising 3 each of Erythrophleum suaveolens, Gmelina arborea and Vitex doniana woods were placed at three different sites (1,2,3) within Nazareth High School Compound Imeko. At each site, 3 hives placed comprised the mixture of the 3 wood species’ hives. Colonisation of hives made of G. arborea and V. doniana woods within two months of placement at the 3 sites were observed. Honeybees colonized E. suaveolens wood hive at site 3 and absconded in the same month of colonisation (October, 2010). Quantitative analysis of the wood samples’ extracts indicated the presence of 39.62mg/g total alkaloids, 1.38mg/g total flavonoids, 84.19mg/g total phenol, 366.52mg/g total Saponins and 101.18mg/g total tannins in E. -

Antineoplastic Potential of the Vitex Species: an Overview

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas BOLETÍN LATINOAMERICANO Y DEL CARIBE DE PLANTAS MEDICINALES Y AROMÁTICAS 17 (5): 492 - 502 (2018) © / ISSN 0717 7917 / www.blacpma.usach.cl Revisión | Review Antineoplastic potential of the Vitex species: An overview [Potencial antineoplásico de la especie Vitex: una visión general] Manisha Nigam1, Sarla Saklani2, Sergey Plygun3,4 & Abhay Prakash Mishra2 1Department of Biochemistry, H. N. B. Garhwal (A Central) University, Srinagar Garhwal, 246174, Uttarakhand, India 2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, H. N. B. Garhwal (A Central) University, Srinagar Garhwal, 246174, Uttarakhand, India 3All Russian Research Institute of Phytopathology, Moscow Region, Russia 4European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Basel, Switzerland Contactos | Contacts: Abhay Prakash MISHRA - E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract: Irrespective of progressive treatments, cancer remains to have the utmost rate of treatment failure due to numerous reasons associated. In recent years, the use of traditional medicine in cancer research has established considerable interest. Natural products represent an amazing source for cancer therapy and combating associated side-effects. More than thousand plants have been found to possess significant anticancer properties. Vitex is the largest genus in the family Lamiaceae which comprises 250 species distributed throughout world and several species have been reported to have anticancer properties. Despite a long tradition of use of some species, the genus has not been explored properly in terms of its anticancer profile. Here we are reporting the updated knowledge of the antineoplastic profile of this genus available so far. -

RESEARCH ARTICLE Vitex Rotundifolia Fractions Induced

DOI:10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.12.3555 Vitex Rotundifolia Fractions Induced Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer T-47D Cell Line RESEARCH ARTICLE Editorial Process: Submission:09/05/2018 Acceptance:11/29/2019 Vitex Rotundifolia Fractions Induced Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer T-47D Cell Line via Activation of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Pathway Gul-e-Saba Chaudhry1*, Rehmat Jan1, Muhammad Naveed Zafar2, Habsah Mohammad1, Tengku Sifzizul Tengku Muhammad1* Abstract Objective: Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide. The main objective of the present study was to evaluate the cytotoxic effects and mechanism of cell death induced by the extract and fractions of Vitex rotundifolia (leaves) in breast cancer cell line, T-47D. Methods: The cytotoxicity activity was measured using MTS assay. The mode of cell death was analysed by early (phosphatidylserine externalization) and late apoptosis (DNA fragmentation). The caspases 8, 9, 3/7 and apoptotic proteins bax, bcl-2 study were done by western blot and ELISA method. Results: The methanol extract was found to inhibit 50% growth of T-47D cells at the concentration of 79.43µg/ ml respectively after 72hr. From seven fractions, fraction F1, F2 and F3 produced cytotoxicity effects in T-47D cell line with IC50 (72hr) < 30µg/ml. The results obtained by Annexin V/PI apoptosis detection assay and TUNEL assay suggest that active fractions of Vitex rotundifolia induced early and late apoptosis (DNA fragmentation) in T-47D cell line. Moreover, western blot analysis and Caspase GloTM luminescent assay demonstrated that fractions F2 and F3 triggered apoptotic cell death via activation of caspases -8, -9 and -3/7 and up-regulation of Bax and down-regulation of Bcl-2 protein. -

Lamiales – Synoptical Classification Vers

Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.6.2 (in prog.) Updated: 12 April, 2016 A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales Version 2.6.2 (This is a working document) Compiled by Richard Olmstead With the help of: D. Albach, P. Beardsley, D. Bedigian, B. Bremer, P. Cantino, J. Chau, J. L. Clark, B. Drew, P. Garnock- Jones, S. Grose (Heydler), R. Harley, H.-D. Ihlenfeldt, B. Li, L. Lohmann, S. Mathews, L. McDade, K. Müller, E. Norman, N. O’Leary, B. Oxelman, J. Reveal, R. Scotland, J. Smith, D. Tank, E. Tripp, S. Wagstaff, E. Wallander, A. Weber, A. Wolfe, A. Wortley, N. Young, M. Zjhra, and many others [estimated 25 families, 1041 genera, and ca. 21,878 species in Lamiales] The goal of this project is to produce a working infraordinal classification of the Lamiales to genus with information on distribution and species richness. All recognized taxa will be clades; adherence to Linnaean ranks is optional. Synonymy is very incomplete (comprehensive synonymy is not a goal of the project, but could be incorporated). Although I anticipate producing a publishable version of this classification at a future date, my near- term goal is to produce a web-accessible version, which will be available to the public and which will be updated regularly through input from systematists familiar with taxa within the Lamiales. For further information on the project and to provide information for future versions, please contact R. Olmstead via email at [email protected], or by regular mail at: Department of Biology, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA. -

Lectin Prospecting in Colombian Labiatae. a Systematic-Ecological Approach – Iii

www.unal.edu.co/icn/publicaciones/caldasia.htm Caldasia 31(2):227-245. 2009 LECTIN PROSPECTING IN COLOMBIAN LABIATAE. A SYSTEMATIC-ECOLOGICAL APPROACH – III. MAINLY EXOTIC SPECIES (CULTIVATED OR NATURALISED) Prospección de lectinas en especies de Labiadas colombianas. Un enfoque sistemático-ecológico – III. Principalmente especies exóti- cas cultivadas o naturalizadas JOSÉ LUIS FERNÁNDEZ-ALONSO Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Apartado 7495, Bogotá D.C., Colombia. [email protected] Real Jardín Botánico CSIC, Plaza de Murillo 2, 28014 Madrid, España, [email protected] NOHORA VEGA Chemistry Department, Biochemistry Laboratory, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. Colombia. [email protected] GERARDO PÉREZ Chemistry Department, Biochemistry Laboratory, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. Colombia. [email protected] ABSTRACT This is the third study of lectin and mucilage detection in Labiatae nutlets from Colombia. It was carried out on 30 taxa; 15 of them belonging to 14 genera in which no previous studies have been carried out in this fi eld, the other 15 belonging to previously studied genera. A differential response was observed in the group of genera and species studied in terms of mucilage presence as well as lectin activity which consistently increased after extract treatment with Pectinex. Lectin activity was detected in 26 species, being important (more than 60% activity) in at least 75% of them. Genera such as Aegiphila, Agastache, Ballota, Mentha and Origanum, whilst not presenting mucilage, did present lectin activity, with high activity in most cases. This is the fi rst time that a lectin has been reported in these genera. Salvia (in all but Salvia sections studied) presented mucilage and important lectin activity.