Wirecard and Greensill Scandals Confirm Dangers of Mixing Banking and Commerce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greensill Capital (UK) Limited-V-Reuters 2020 EWHC 1325

Neutral Citation Number: [2020] EWHC 1325 (QB) Case No: QB-2019-002773 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION MEDIA & COMMUNICATIONS LIST Date: 14 May 2020 Before: THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE NICKLIN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: (1) GREENSILL CAPITAL (UK) LIMITED (2) ALEXANDER GREENSILL Claimants - and – REUTERS NEWS AND MEDIA LIMITED Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Adrienne Page QC and Jonathan Barnes (instructed by Schillings International LLP) appeared on behalf of the Claimants Catrin Evans QC (instructed by Pinsent Masons LLP) appeared on behalf of the Defendant Hearing date: 14 May 2020 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment This Transcript is Crown Copyright. It may not be reproduced in whole or in part other than in accordance with relevant licence or with the express consent of the Authority. All rights are reserved. Digital Transcription by Marten Walsh Cherer Ltd., 2nd Floor, Quality House, 6-9 Quality Court, Chancery Lane, London WC2A 1HP. Telephone No: 020 7067 2900. Fax No: 020 7831 6864 DX 410 LDE Email: [email protected] Web: www.martenwalshcherer.com The Honourable Mr Justice Nicklin Greensill Capital & Another -v- Reuters Approved Judgment 14.05.20 MR JUSTICE NICKLIN : 1. This is a claim for libel. As set out in the Particulars of Claim, the First Claimant is a financial services company that specialises in supply chain finance and securitising future guarantee cashflows. The Second Claimant founded the First Claimant in 2011 and he is its Chief Executive Officer. 2. The Defendant is a well-known international news publisher. The UK edition of its website can be found at uk.reuters.com (“the Website”). 3. From around midday on 7 July 2019, the Defendant published an article on the Website in the Business News section under the headline: “Exclusive: Greensill issued false statement on bonds sold by metals tycoon Gupta” (“the Article”). -

Treasury Committee Oral Evidence: Lessons from Greensill Capital, HC 151

Treasury Committee Oral evidence: Lessons from Greensill Capital, HC 151 Tuesday 11 May 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 11 May 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Mel Stride (Chair); Rushanara Ali; Mr Steve Baker; Harriett Baldwin; Anthony Browne; Felicity Buchan; Dame Angela Eagle; Emma Hardy; Julie Marson; Siobhain McDonagh; Alison Thewliss. Questions 84-294 Witnesses I: Alexander Greensill CBE. Examination of witness Witness: Lex Greensill. Q84 Chair: Good afternoon and welcome to the Treasury Committee evidence session on the lessons from Greensill Capital. We are very pleased to be joined by one witness this afternoon, Lex Greensill. Lex, welcome to the Committee. For the public record, could I ask you very briefly to introduce yourself to the Committee? I believe that you have a short statement that you would like to make to the Committee, so can you make your brief introduction and statement, please? Lex Greensill: My name is Lex Greensill. Thank you for the opportunity to participate in this important hearing and to answer your questions, and I hope to provide clarity and greater understanding of the issues before us. Please understand that I bear complete responsibility for the collapse of Greensill Capital. I am desperately saddened that more than 1,000 very hard-working people have lost their jobs at Greensill. Likewise, I take full responsibility for any hardship being felt by our clients and their suppliers, and indeed by investors in our programmes. It is deeply regrettable that we were let down by our leading insurer, whose actions ensured Greensill’s collapse, and indeed by some of our biggest customers. -

VISA Europe AIS Certified Service Providers

Visa Europe Account Information Security (AIS) List of PCI DSS validated service providers Effective 08 September 2010 __________________________________________________ The companies listed below successfully completed an assessment based on the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). 1 The validation date is when the service provider was last validated. PCI DSS assessments are valid for one year, with the next annual report due one year from the validation date. Reports that are 1 to 60 days late are noted in orange, and reports that are 61 to 90 days late are noted in red. Entities with reports over 90 days past due are removed from the list. It is the member’s responsibility to use compliant service providers and to follow up with service providers if there are any questions about their validation status. 2 Service provider Services covered by Validation date Assessor Website review 1&1 Internet AG Internet payment 31 May 2010 SRC Security www.ipayment.de processing Research & Consulting Payment gateway GmbH Payment processing a1m GmbH Payment gateway 31 October 2009 USD.de AG www.a1m.biz Internet payment processing Payment processing A6IT Limited Payment gateway 30 April 2010 Kyte Consultants Ltd www.A6IT.com Abtran Payment processing 31 July 2010 Rits Information www.abtran.com Security Accelya UK Clearing and Settlement 31 December 2009 Trustwave www.accelya.com ADB-UTVECKLING AB Payment gateway 30 November 2009 Europoint Networking WWW.ADBUTVECKLING.SE AB Adeptra Fraud Prevention 30 November 2009 Protiviti Inc. www.adeptra.com Debt Collection Card Activation Adflex Payment Processing 31 March 2010 Evolution LTD www.adflex.co.uk Payment Gateway/Switch Clearing & settlement 1 A PCI DSS assessment only represents a ‘snapshot’ of the security in place at the time of the review, and does not guarantee that those security controls remain in place after the review is complete. -

Global Potential for Prepaid Cards

Global Potential for Prepaid Cards Overview of Key Markets September 2018 © Edgar, Dunn & Company, 2018 Edgar, Dunn & Company (EDC) is an independent global financial services and payments strategy consultancy EDC - Independent, Global and Strategic EDC Office Locations Founded in 1978, the firm is widely regarded as a trusted advisor to its clients, providing a full range of strategy consulting services, expertise and market insight, and M&A support EDC has been providing thought leadership to its client base working with: More than 40 European banks & card issuers/acquirers London Frankfurt Most of the top 25 US banks and credit card issuers San Paris Istanbul All major international card associations / schemes & Francisco many domestic card schemes Many of the world's most influential mobile payments providers Many of the world's leading merchants, including Sydney major airlines Office locations Shaded blue countries represent markets where EDC conducted client engagements EDC Key Metrics Financial services and payments focus +1,000 projects completed Six office locations worldwide +250 clients in 40 countries & 6 continents Independent - owned and controlled by EDC Directors Confidential 2 EDC has deep expertise in across seven specialist practice areas M&A Practice Legal & Travel Regulatory Practice Practice Fintech Retail Practice Practice Issuing Acquiring Practice Practice Confidential 3 A global perspective of prepaid from a truly global strategy consulting firm Countries where Edgar, Dunn & Company has delivered projects Confidential 4 The global prepaid card market is expected to reach $3.7 trillion by 2022 - a growth of 22.7% from 2016 to 20221 $3.7tn size of global prepaid market by 2022 Confidential 1Allied Market Research 2017 5 What we will cover today…. -

How Mpos Helps Food Trucks Keep up with Modern Customers

FEBRUARY 2019 How mPOS Helps Food Trucks Keep Up With Modern Customers How mPOS solutions Fiserv to acquire First Data How mPOS helps drive food truck supermarkets compete (News and Trends) vendors’ businesses (Deep Dive) 7 (Feature Story) 11 16 mPOS Tracker™ © 2019 PYMNTS.com All Rights Reserved TABLEOFCONTENTS 03 07 11 What’s Inside Feature Story News and Trends Customers demand smooth cross- Nhon Ma, co-founder and co-owner The latest mPOS industry headlines channel experiences, providers of Belgian waffle company Zinneken’s, push mPOS solutions in cash-scarce and Frank Sacchetti, CEO of Frosty Ice societies and First Data will be Cream, discuss the mPOS features that acquired power their food truck operations 16 23 181 Deep Dive Scorecard About Faced with fierce eTailer competition, The results are in. See the top Information on PYMNTS.com supermarkets are turning to customer- scorers and a provider directory and Mobeewave facing scan-and-go-apps or equipping featuring 314 players in the space, employees with handheld devices to including four additions. make purchasing more convenient and win new business ACKNOWLEDGMENT The mPOS Tracker™ was done in collaboration with Mobeewave, and PYMNTS is grateful for the company’s support and insight. PYMNTS.com retains full editorial control over the findings presented, as well as the methodology and data analysis. mPOS Tracker™ © 2019 PYMNTS.com All Rights Reserved February 2019 | 2 WHAT’S INSIDE Whether in store or online, catering to modern consumers means providing them with a unified retail experience. Consumers want to smoothly transition from online shopping to browsing a physical retail store, and 56 percent say they would be more likely to patronize a store that offered them a shared cart across channels. -

A Case of Corporate Deceit: the Enron Way / 18 (7) 3-38

NEGOTIUM Revista Científica Electrónica Ciencias Gerenciales / Scientific e-journal of Management Science PPX 200502ZU1950/ ISSN 1856-1810 / By Fundación Unamuno / Venezuela / REDALYC, LATINDEX, CLASE, REVENCIT, IN-COM UAB, SERBILUZ / IBT-CCG UNAM, DIALNET, DOAJ, www.jinfo.lub.lu.se Yokohama National University Library / www.scu.edu.au / Google Scholar www.blackboard.ccn.ac.uk / www.rzblx1.uni-regensburg.de / www.bib.umontreal.ca / [+++] Cita / Citation: Amol Gore, Guruprasad Murthy (2011) A CASE OF CORPORATE DECEIT: THE ENRON WAY /www.revistanegotium.org.ve 18 (7) 3-38 A CASE OF CORPORATE DECEIT: THE ENRON WAY EL CASO ENRON. Amol Gore (1) and Guruprasad Murthy (2) VN BRIMS Institute of Research and Management Studies, India Abstract This case documents the evolution of ‘fraud culture’ at Enron Corporation and vividly explicates the downfall of this giant organization that has become a synonym for corporate deceit. The objectives of this case are to illustrate the impact of culture on established, rational management control procedures and emphasize the importance of resolute moral leadership as a crucial qualification for board membership in corporations that shape the society and affect the lives of millions of people. The data collection for this case has included various sources such as key electronic databases as well as secondary data available in the public domain. The case is prepared as an academic or teaching purpose case study that can be utilized to demonstrate the manner in which corruption creeps into an ambitious organization and paralyses the proven management control systems. Since the topic of corporate practices and fraud management is inherently interdisciplinary, the case would benefit candidates of many courses including Operations Management, Strategic Management, Accounting, Business Ethics and Corporate Law. -

Official Versions Vs Facts

1 This text below is inspired by a translation from a French text that was published on the website of Paul Jorion in late June 2017, ie about only 2 weeks after this website would go live. I answered here a very straight question: “how do you differ from the official version?” And here is my “story”, the only one that have conveyed since 2012. It was then meant to summarize how my website differs from all the reports that the bank and the authorities have made on the “London Whale” case. It was 143 pages long for Paul Jorion. Now it is 29 pages long. What I have added are further details on key topics like ‘profits’, like ‘orders’, like ‘valuation’, like ‘mismarking’…. Needless to say, this account vastly differs from any media reporting although some outlets are closer than others. This text below thus predated by a month or so the decisions of the DOJ as disclosed on July 21st 2017. It may well have been the “recent statements and writings” that would shake the tree. It contradicted ahead of times the WSJ subsequent article of August 3rd 2017. Yet it corroborated the statements of Dimon on August 8th 2017 to some extent and clarified ahead of times the context of the ultimate decision of the SEC in late August 2017. But, back in June 2017, this text was also displaying my ‘story’ as an anchor amid all the changing stories that would have been conveyed since 2012 and onwards… In sharp contrast to what all the authorities and the bank would do between 2012 and 2018, I will deploy only one “story” to tell all along, be that on the public stage or confidentially towards the authorities. -

A Recap of Recent Financial and Economic Market Activity. Applications for U.S

Samuel Mangiapane, CRPC®, MBA Managing Principal | Financial Advisor Chartered Retirement Planning Counselor℠ 732-807-2340 direct [email protected] email mintfinancialservicesllc.com website Mint Financial Services LLC 2-10 Broad Street, Suite 303 Red Bank, NJ 07701 July 2021 - A recap of recent financial and economic market activity. Applications for U.S. state unemployment insurance fell by more than projected, reaching a fresh pandemic low. U.S. manufacturing continued to expand at a solid, yet slightly slower pace while a measure of prices paid for materials jumped to an almost 42-year high. Year to date, cyclicals have been some better performers. Energy shares are up 44.5% with the rebound in oil prices, and financials have bounced 25.2%. In contrast, S&P 500 growth stocks are up 14.3%, lagging slightly the S&P 500’s 15.5% gain. Tech stocks are up 14.9% year-to-date. Oil jumped to the highest in more than six years after a bitter fight between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates plunged OPEC+ into crisis and blocked a supply increase. Fearful of their growing influence, China is in the middle of a sweeping crackdown on the nation's biggest tech firms. Last November, Beijing pulled the planned IPO of fintech giant Ant Group, and in April, it hit Alibaba (BABA) with a record $2.8B fine over abusing its market dominance. The Fed delivered a double-whammy after its quarterly economic forecasts showed officials expect two rate hikes in 2023 and Chair Jerome Powell announced the central bank was getting the taper debate into gear. -

Pulse of Fintech H2 2019

Pulse of Fintech H2 2019 February 2020 Welcome message Welcome to the 2019 end-of-year edition of KPMG’s Pulse of Fintech — KPMG Fintech professionals a biannual report highlighting key trends and activities within the fintech include partners and staff in over market globally and in key jurisdictions around the world. 50 fintech hubs around theworld, working closely with financial After a massive year of investment in 2018, total global fintech institutions, digital banks and fintech investment remained high in 2019 with over $135.7 billion invested companies to help them understand globally across M&A, PE and VC deals. While the total number of fintech the signals of change, identify the deals declined, the fintech market saw median VC deal sizes grow in growth opportunities, and develop most jurisdictions around the world as maturing fintechs attracted larger and execute their strategicplans. funding rounds. Fintech-focused M&A activity was also very strong, propelled by a record-shattering quarterly high of $66.85 billion in M&A investment in Q3’19. The Americas and Europe both saw strong levels of fintech investment during 2019. In Asia, total annual fintech investment dropped compared to 2018’s massive peak high. However, on a quarterly basis it remained quite steady compared to all but the massive outlier quarter that was Q2’18. All jurisdictions saw a decline in their fintech deal volume during 2019 — a fact that reflects the growing maturity of fintech companies and the increasing focus of investors on late-stage and follow-on deals. Payments, including digital banking, remained the hottest area of fintech investment globally, with a significant amount of focus on mature startups working to expand geographically or to grow their product breadth. -

Global Fintech Biweekly Vol.18 Aug 28, 2020 Global

Friday Global FinTech Biweekly vol.18 Aug 28, 2020 Highlight of this issue – Global payment giants 2Q20 results: the pandemic accelerates payment digitalization Figure 1: PayPal outperformed peers with its online payment strength Source: Company disclosure, AMTD Research Note: 1) Square’s big loss in non-GAAP net income in 1Q20 was mainly due to the increase in provision for transaction and loan losses; if excluding the item, the 1Q20 YoY growth of non-GAAP net income would be 23%. 2) For Visa, 4Q19, 1Q20 and 2Q20 refer to 1QFY20, 2QFY20 and 3QFY20, respectively. Global payment giants beat expectations in 2Q20; online and contactless payments uplifted earnings Global payment giants’ 2Q20 results outperformed market consensus on the whole. Although the offline payments and cross-border payments experienced a heavy blow, contactless payments and online payments expanded dramatically and partially offset the declines. PayPal, which focuses on online payments, posted record growth, with its gross payment volume (GPV), adjusted net income and net margin all reaching their historic highs. As the world has entered a new phase in the fight against the pandemic, the global consumer payment market gradually recovers, and the GPVs of payment giants improve month by month since April. Online payments in the US grew rapidly in the quarter, while offline payment volume declined less than expected due to the US economic stimulus package. China's consumer spending recovery unfolded as the pandemic went under control. In both developed and developing markets, offline contactless payments and online digital payments penetration rates are fast increasing, and payment giants are strengthening their digital offerings to ride on the contactless digitalization trend. -

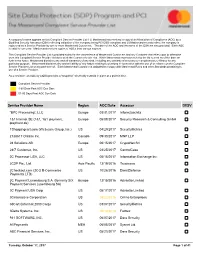

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV “BPC Processing”, LLC Europe 03/31/2017 Informzaschita 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

2 Bureaucratic Autonomy: Logic, Theory, and Design 18 2.1 Introduction

Charting a Course to Autonomy: Bureaucratic Politics and the Transformation of Wall Street by Peter Joseph Ryan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Paul Pierson, Chair Professor J. Nicholas Ziegler Professor Neil Fligstein Spring 2013 Charting a Course to Autonomy: Bureaucratic Politics and the Transformation of Wall Street Copyright c 2013 by Peter Joseph Ryan Abstract Charting a Course to Autonomy: Bureaucratic Politics and the Transformation of Wall Street by Peter Joseph Ryan Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Paul Pierson, Chair Over the past three decades, federal regulators have been at the heart of transformations that have reshaped the financial services industry in the United States and by definition, global markets. It was, for example, the Federal Reserve that initiated and developed risk- based capital standards, rules that are now at the heart of prudential regulation of financial firms across the globe. Federal regulators played a central role in preventing regulation of the emerging ‘over-the-counter’ derivatives market in the late 1980s and early 1990s, actions that later had dramatic consequences during the 2007-2008 financial crisis. The Securities and Exchange Commission took critical decisions regarding the prudential supervision of investment banks, decisions that greatly contributed to the end of the independent invest- ment banking industry in the United States in 2008. Finally regulators played an important role in setting the agenda and shaping the outcomes of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act of 2010, the most sweeping and comprehensive piece of legislation affecting the industry since the New Deal.