Evaluation of UNESCO's Action to Revitalize and Promote Indigenous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marie Laing M.A. Thesis

Conversations with Young Two-Spirit, Trans and Queer Indigenous People About the Term Two-Spirit by Marie Laing A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Social Justice Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Marie Laing 2018 Conversations with Young Two-Spirit, Trans and Queer Indigenous People About the Term Two-Spirit Marie Laing Master of Arts Department of Social Justice Education University of Toronto 2018 Abstract Since the coining of the term in 1990, two-spirit has been used with increasing frequency in reference to Indigenous LGBTQ people; however, there is rarely explicit discussion of to whom the term two-spirit refers. The word is often simultaneously used as both an umbrella term for all Indigenous people with complex genders or sexualities, and with the specific, literal understanding that two-spirit means someone who has two spirits. This thesis discusses findings from a series of qualitative interviews with young trans, queer and two-spirit Indigenous people living in Toronto. Exploring the ways in which participants understand the term two-spirit to be a meaningful and complex signifier for a range of ways of being in the world, this paper does not seek to define the term two-spirit; rather, following the direction of research participants, the thesis instead seeks to trouble the idea that articulating a definition of two-spirit is a worthwhile undertaking. ii Acknowledgments There are many people without whom I would not have been able to complete this research. Thank you to my supervisor, Dr. -

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 The first UN Infantry Battalion was deployed as part of United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF-I). UN infantry soldiers march in to Port Said, Egypt, in December 1956 to assume operational responsibility. asdf ‘The United Nations Infantry Battalion is the backbone of United Nations peacekeeping, braving danger, helping suffering civilians and restoring stability across war-torn societies. We salute your powerful contribution and wish you great success in your life-saving work.’ BAN Ki-moon United Nations Secretary-General United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual ii Preface I am very pleased to introduce the United Nations Infantry Battalion Man- ual, a practical guide for commanders and their staff in peacekeeping oper- ations, as well as for the Member States, the United Nations Headquarters military and other planners. The ever-changing nature of peacekeeping operations with their diverse and complex challenges and threats demand the development of credible response mechanisms. In this context, the military components that are deployed in peacekeeping operations play a pivotal role in maintaining safety, security and stability in the mission area and contribute meaningfully to the achievement of each mission mandate. The Infantry Battalion con- stitutes the backbone of any peacekeeping -

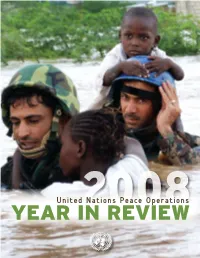

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Aboriginal Two-Spirit and LGBTQ Mobility

Aboriginal Two-Spirit and LGBTQ Mobility: Meanings of Home, Community and Belonging in a Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Interviews by Lisa Passante A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2012 by Lisa Passante ABORIGINAL TWO-SPIRIT & LGBTQ HOME, COMMUNITY, AND BELONGING Abstract This thesis reports on a secondary analysis of individual and focus group interviews from the Aboriginal Two-Spirit and LGBTQ Migration, Mobility and Health research project (Ristock, Zoccole, and Passante, 2010; Ristock, Zoccole, & Potskin, 2011). This was a community-based qualitative research project following Indigenous and feminist methods, involving two community Advisory Committees, and adopting research principles of Ownership Control Access and Possession (OCAP) (First Nations Centre, 2007). This analysis reviews data from 50 participants in Winnipeg and Vancouver and answers: How do Aboriginal Two-Spirit and LGBTQ people describe home, community and belonging in the context of migration, multiple identities, and in a positive framework focusing on wellbeing, strengths and resilience? Findings demonstrate how participants experience marginalization in both Aboriginal and gay communities. Their words illustrate factors such as safety required to facilitate positive identities, community building, belonging, and sense of home. For participants in this study home is a place where they can bring multiple identities, a geographical place, a physical or metaphorical space (with desired tone, feeling), and a quality of relationships. Community is about places, relationships, participation, and shared interests. Belonging is relational and interactive, feeling safe, accepted, and welcome to be yourself. -

The Vocabulary of Inanimate Nature As a Part of Turkic-Mongolian Language Commonness

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 6 S2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy November 2015 The Vocabulary of Inanimate Nature as a Part of Turkic-Mongolian Language Commonness Valentin Ivanovich Rassadin Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor, Department of the Kalmyk language and Mongolian studies Director of the Mongolian and Altaistic research Scientific centre, Kalmyk State University 358000, Republic of Kalmykia, Elista, Pushkin street, 11 Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n6s2p126 Abstract The article deals with the problem of commonness of Turkic and Mongolian languages in the area of vocabulary; a layer of vocabulary, reflecting the inanimate nature, is subject to thorough analysis. This thematic group studies the rubrics, devoted to landscape vocabulary, different soil types, water bodies, atmospheric phenomena, celestial sphere. The material, mainly from Khalkha-Mongolian and Old Written Mongolian languages is subject to the analysis; the data from Buryat and Kalmyk languages were also included, as they were presented in these languages. The Buryat material was mainly closer to the Khalkha-Mongolian one. For comparison, the material, mainly from the Old Turkic language, showing the presence of similar words, was included; it testified about the so-called Turkic-Mongolian lexical commonness. The analysis of inner forms of these revealed common lexemes in the majority of cases allowed determining their Turkic origin, proved by wide occurrence of these lexemes in Turkic languages and Turkologists' acknowledgement of their Turkic origin. The presence of great quantity of common vocabulary, which origin is determined as Turkic, testifies about repeated ancient contacts of Mongolian and Turkic languages, taking place in historical retrospective, resulting in hybridization of Mongolian vocabulary. -

Reputation As a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected]

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2019 Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2035 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, Organizations Law Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Daugirdas, Kristina. "Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations." Am. J. Int'l L. 113, no. 2 (2019): 221-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2019 by The American Society of International Law doi:10.1017/ajil.2018.122 REPUTATION AS A DISCIPLINARIAN OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS By Kristina Daugirdas* ABSTRACT As a disciplinarian of international organizations, reputation has serious shortcomings. Even though international organizations have strong incentives to maintain a good reputation, reputational concerns will sometimes fail to spur preventive or corrective action. Organizations have multiple audiences, so efforts to preserve a “good” reputation may pull organizations in many different directions, and steps taken to preserve a good reputation will not always be salutary. Recent incidents of sexual violence by UN peacekeepers in the Central African Republic illustrate these points. On April 29, 2015, The Guardian published an explosive story based on a leaked UN document.1 The document described allegations against French troops who had been deployed to the Central African Republic pursuant to a mandate established by the Security Council. -

Reconstructing the Population History of the Largest Tribe of India: the Dravidian Speaking Gond

European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 493–498 & 2017 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 1018-4813/17 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Reconstructing the population history of the largest tribe of India: the Dravidian speaking Gond Gyaneshwer Chaubey*,1, Rakesh Tamang2,3, Erwan Pennarun1,PavanDubey4,NirajRai5, Rakesh Kumar Upadhyay6, Rajendra Prasad Meena7, Jayanti R Patel4,GeorgevanDriem8, Kumarasamy Thangaraj5, Mait Metspalu1 and Richard Villems1,9 The Gond comprise the largest tribal group of India with a population exceeding 12 million. Linguistically, the Gond belong to the Gondi–Manda subgroup of the South Central branch of the Dravidian language family. Ethnographers, anthropologists and linguists entertain mutually incompatible hypotheses on their origin. Genetic studies of these people have thus far suffered from the low resolution of the genetic data or the limited number of samples. Therefore, to gain a more comprehensive view on ancient ancestry and genetic affinities of the Gond with the neighbouring populations speaking Indo-European, Dravidian and Austroasiatic languages, we have studied four geographically distinct groups of Gond using high-resolution data. All the Gond groups share a common ancestry with a certain degree of isolation and differentiation. Our allele frequency and haplotype-based analyses reveal that the Gond share substantial genetic ancestry with the Indian Austroasiatic (ie, Munda) groups, rather than with the other Dravidian groups to whom they are most closely related linguistically. European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 493–498; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2016.198; published online 1 February 2017 INTRODUCTION material cultures, as preserved in the archaeological record, were The linguistic landscape of India is composed of four major language comparatively less developed.10–12 The combination of the more families and a number of language isolates and is largely associated rudimentary technological level of development of the resident with non-overlapping geographical divisions. -

Hip-Hop, Language, and Indigeneity in the Americas

CRS0010.1177/0896920515569916Critical SociologyNavarro 569916research-article2015 Article Critical Sociology 1 –15 WORD: Hip-Hop, Language, and © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Indigeneity in the Americas sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0896920515569916 crs.sagepub.com Jenell Navarro California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, USA Abstract Indigenous hip-hop artists throughout the Americas are currently challenging cultural genocide and contemporary post-racial discourse by utilizing ancestral languages in hip-hop cultural production. While the effects of settler colonialism and white supremacy have been far-reaching genocidal projects throughout the Americas, one primary site of resistance has been language. Artists such as Tall Paul (Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe), Tolteka (Mexica), and Los Nin (Quecha), who rap in Ojibwe, Nahuatl, and Kichwa respectively, trouble the pervasive structure of U.S. cultural imperialism that persists throughout the Americas. As a result, Indigenous hip-hop is a medium to engage the process of decolonization by 1) disseminating a conscious pan-indigeneity through lyricism and alliance building, 2) retaining and teaching Indigenous languages in their songs, and 3) implementing a radical orality in their verses that revitalizes both Indigenous oral traditions/ storytelling and the early message rap of the 1970s and 1980s. Keywords decolonization, hip-hop, Indigenous language, Indigenous studies, post-racial Introduction When asserting the political importance of Indigenous hip-hop, it is important to begin by thinking about the context for the emergence of hip-hop music and culture in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the South Bronx. In the 1970s, the United States witnessed a reaction directly against the Civil Rights movements and the gains that it made for racial equality. -

Lost for Words Maria Mikulcova

Lost for Words Effects of Soviet Language Policies on the Self-Identification of Buryats in Post-Soviet Buryatia Maria Mikulcova A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of MA Russian and Eurasian Studies Leiden University June 2017 Supervisor: Dr. E.L. Stapert i Abstract Throughout the Soviet rule Buryats have been subjected to interventionist legislation that affected not only their daily lives but also the internal cohesion of the Buryat group as a collective itself. As a result of these measures many Buryats today claim that they feel a certain degree of disconnection with their own ethnic self-perception. This ethnic estrangement appears to be partially caused by many people’s inability to speak and understand the Buryat language, thus obstructing their connection to ancient traditions, knowledge and history. This work will investigate the extent to which Soviet linguistic policies have contributed to the disconnection of Buryats with their own language and offer possible effects of ethnic language loss on the self-perception of modern day Buryats. ii iii Declaration I, Maria Mikulcova, declare that this MA thesis titled, ‘Lost for Words - Effects of Soviet Language Policies on the Self-Identification of Buryats in Post-Soviet Buryatia’ and the work presented in it are entirely my own. I confirm that: . This work was done wholly while in candidature for a degree at this University. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. -

Horizontal Inequality in Chiapas – 25 Years After the Zapatista Movement

Master’s Programme in Economic Growth, Development and Population Horizontal Inequality in Chiapas – 25 years after the Zapatista Movement by Juliane Koch [email protected] Abstract: The International Development Community places individuals at the center of concern for policy making. This study investigates why group analyses are crucial for the welfare of individual and social stability, and claims that the concept of Horizontal Inequality (group-based inequality) is important but widely neglected. The group of investigation is the indigenous population in Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest state. Since their initial protests in 1994, they demand more rights and a more equal society. The research at hand shows that little has changed since then as the indigenous population still lags behind in terms of socio- economic indicators. Apart from providing patterns over time, this study finds that the indigenous population in Chiapas is worse off than in other Mexican states. This demonstrates that the prevalence of high economic and social inequality patterns still hinder Chiapas’ indigenous population from improving their poor living standards. Thus, this thesis concludes with policy implications and a call for strengthening efforts on behalf of the Mexican government. Key words: horizontal inequality, indigenous population, poverty, chiapas EKHS21 Master’s Thesis (15 credits ECTS) 29-05-2019 Supervisor: Edoardo Altamura Examiner: Word Count: 15,971 Acknowledgements I am highly grateful to Frances Stewart and Alicia Puyana for their valuable advice and comments about the concept of this thesis and its methodology. Furthermore, I thank the National Council for Evaluation of Social Development Policy in Mexico for providing me with extensive datasets and clarifications. -

Official Journal C327

ISSN 1725-2423 Official Journal C 327 of the European Union Volume 49 English edition Information and Notices 30 December 2006 Notice No Contents Page I Information EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2006/C 327/01 WRITTEN QUESTIONS WITH ANSWER List of titles of Written Questions by Members of the European Parliament indicating the number, original language, author, political group, institution addressed, date submitted and subject of the question .................................... 1 (See notice to readers) EN Price: 34 EUR Note to readers Written questions with answers tabled during the sixth parliamentary term are no longer available in all the official languages; the title only is translated into 19 languages (not Maltese). P and E questions are translated by Parliament into the 11 ‘old’ languages and into the author’s language if it is one of the 2004 enlargement languages. As regards answers to questions, the situation is more complicated: — Answers prepared by the Commission are supplied only in the author’s language and in either English or French, as requested; — The Council gives answers only in the 11 old Union languages. In the light of this situation, readers seeking details of the substance of questions and answers should go to Parliament’s website (Europarl) and, more specifically, the ‘Parliamentary questions’ heading: http://www. europarl.europa.eu/QP-WEB. Should the language version the reader is seeking not be available, Europarl will propose an alternative. ABBREVIATIONS USED FOR POLITICAL GROUPS PPE-DE Group of the European People’s -

Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities

Dr. K. Warikoo 1 © Vivekananda International Foundation 2020 Published in 2020 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg | Chanakyapuri | New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764 | Fax: 011-66173415 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vifindia.org Follow us on Twitter | @vifindia Facebook | /vifindia All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher Dr. K. Warikoo is former Professor, Centre for Inner Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is currently Senior Fellow, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi. This paper is based on the author’s writings published earlier, which have been updated and consolidated at one place. All photos have been taken by the author during his field studies in the region. Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities India and Eurasia have had close social and cultural linkages, as Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia, Mongolia, Buryatia, Tuva and far wide. Buddhism provides a direct link between India and the peoples of Siberia (Buryatia, Chita, Irkutsk, Tuva, Altai, Urals etc.) who have distinctive historico-cultural affinities with the Indian Himalayas particularly due to common traditions and Buddhist culture. Revival of Buddhism in Siberia is of great importance to India in terms of restoring and reinvigorating the lost linkages. The Eurasianism of Russia, which is a Eurasian country due to its geographical situation, brings it closer to India in historical-cultural, political and economic terms.