Download and Complete the Most Invasive Paperwork of My Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

Roy Thomas ’Merry Mar vel Comics Fan zine No. 50 July 2005 $ In5th.e9U5SA Sub-Mariner, Thing, Thor, & Vision TM & ©2005 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Conan TM & ©2005 Conan Properties, Inc.; Red Sonja TM & ©2005 Red Sonja Properties, Inc.; Caricature ©2005 Estate of Alfredo Alcala Vol. 3, No. 50 / July 2005 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Roy Thomas Associate Editors Shamelessly Celebrates Bill Schelly 50 Issues of A/E , Vol. 3— Jim Amash & 40 Years Since Design & Layout Christopher Day Modeling With Millie #44! Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Contents Mike Friedrich Production Assistant Writer/Editorial: Make Mine Marvel! . 2 Eric Nolen-Weathington “Roy The Boy” In The Marvel Age Of Comics . 4 Cover Artists Jim Amash interviews Roy Thomas about being Stan Lee’s “left-hand man” Alfredo Alcala, John Buscema, in the 1960s & early ’70s. & Jack Kirby Jerry Ordway DC Comics 196 5––And The Rest Of Roy’s Cover Colorist Color-Splashed Career . Flip Us! Alfredo Alcala (portrait), Tom Ziuko About Our Cover: A kaleidoscopically collaborative combination of And Special Thanks to: three great comic artists Roy worked with and admired in the 1960s and Alfredo Alcala, Jr. Allen Logan ’70s: Alfredo Alcala , John Buscema , and Jack Kirby . The painted Christian Voltan Linda Long caricature by Alfredo was given to him as a birthday gift in 1981 and Alcala Don Mangus showed Rascally Roy as Conan, the Marvel-licensed hero on which the Estelita Alcala Sam Maronie Heidi Amash Mike Mikulovsky two had labored together until 1980, when R.T. -

Fudge the Elf

1 Fudge The Elf Ken Reid The Laura Maguire collection Published October 2019 All Rights Reserved Sometime in the late nineteen nineties, my daughter Laura, started collecting Fudge books, the creation of the highly individual Ken Reid. The books, the daily strip in 'The Manchester Evening News, had been a part of my childhood. Laura and her brother Adam avidly read the few dog eared volumes I had managed to retain over the years. In 2004 I created a 'Fudge The Elf' website. This brought in many contacts, collectors, individuals trying to find copies of the books, Ken's Son, the illustrator and colourist John Ridgeway, et al. For various reasons I have decided to take the existing website off-line. The PDF faithfully reflects the entire contents of the original website. Should you wish to get in touch with me: [email protected] Best Regards, Peter Maguire, Brussels 2019 2 CONTENTS 4. Ken Reid (1919–1987) 5. Why This Website - Introduction 2004 6. Adventures of Fudge 8. Frolics With Fudge 10. Fudge's Trip To The Moon 12. Fudge And The Dragon 14. Fudge In Bubbleville 16. Fudge In Toffee Town 18. Fudge Turns Detective Savoy Books Editions 20. Fudge And The Dragon 22. Fudge In Bubbleville The Brockhampton Press Ltd 24. The Adventures Of Dilly Duckling Collectors 25. Arthur Gilbert 35. Peter Hansen 36. Anne Wilikinson 37. Les Speakman Colourist And Illustrator 38. John Ridgeway Appendix 39. Ken Reid-The Comic Genius 3 Ken Reid (1919–1987) Ken Reid enjoyed a career as a children's illustrator for more than forty years. -

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony Tahanie Aboushi | New York, New York I am counsel for Dounya Zayer, the protestor who was violently shoved by officer D’Andraia and observed by Commander Edelman. I would like to appear with Dounya to testify at this hearing and I will submit written testimony at a later time but well before the June 15th deadline. Thank you. Marissa Abrahams | South Beach Psychiatric Center | Brooklyn, New York As a nurse, it has been disturbing to see first-hand how few NYPD officers (present en masse at ALL peaceful protests) are wearing the face masks that we know are preventing the spread of COVID-19. Demonstrators are taking this extremely seriously and I saw NYPD literally laugh in the face of a protester who asked why they do not. It is negligent and a blatant provocation -especially in the context of the over-policing of Black and Latinx communities for social distancing violations. The complete disregard of the NYPD for the safety of the people they purportedly protect and serve, the active attacks with tear gas and pepper spray in the midst of a respiratory pandemic, is appalling and unacceptable. Aaron Abrams | Brooklyn, New York I will try to keep these testimonies as precise as possible since I know your office likely has hundreds, if not thousands to go through. Three separate occasions highlighted below: First Incident - May 30th - Brooklyn - peaceful protestors were walking from Prospect Park through the streets early in the day. At one point, police stopped to block the street and asked that we back up. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Political Intelligibility and the Performative Force of Assembly Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/62t2t12z Author Liou, Stacey Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Political Intelligibility and the Performative Force of Assembly DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Political Science by Stacey Liou Dissertation Committee: Professor Kevin Olson, Chair Professor Simone Chambers Associate Professor Keith Topper © 2020 Stacey Liou DEDICATION To Ryan sine non qua ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii VITA vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 How Materiality Matters 21 CHAPTER 2 Collectivity as Performative Force 51 CHAPTER 3 Publicity and the Disorders of Desire 93 CHAPTER 4 Affect and Horizons of Concern 128 CONCLUSION 164 BIBLIOGRAPHY 170 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have been waiting a long time for this opportunity to acknowledge the generosity, guidance and company of friends, colleagues and family. A life spent between books and screen can be lonely, and I’m lucky that you all have made it richer and more rewarding for your presence. My first thanks are to Kevin Olson, Simone Chambers and Keith Topper. Kevin, Simone and Keith have challenged me to think coherently, precisely and creatively, and my intellectual development results in no small part from their tireless efforts in this regard. They model a form of scholarship committed to thoughtful, lively and fun conversation, and I only hope to follow the examples they have set. -

A Look at How Stan Lee Helped Create the Modern Superhero Movie. P4-5

Community Community The Day Precious That Went Gudza, P7Missing is P16 Zimbabwean a profoundly hairstylist in Doha, talks moving study of about her journey to memory, denial modern hairstyles and her and grief. future goals and aspirations. Thursday, November 15, 2018 Rabia I 7, 1440 AH Doha today: 240 - 320 COVER Lee’s legacy STORY A look at how Stan Lee helped create the modern superhero movie. P4-5 REVIEWS SHOWBIZ Widows elevates pulpy political All of us are here thriller to high art. to do a job: Sara. Page 14 Page 15 2 GULF TIMES Thursday, November 15, 2018 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 4.31am Shorooq (sunrise) 5.50am Zuhr (noon) 11.18am Asr (afternoon) 2.24pm Maghreb (sunset) 4.48pm Isha (night) 6.18pm USEFUL NUMBERS Bohemian Rhapsody turn Freddie, surrounded by darker infl uences, shuns Queen DIRECTION: Bryan Singer in pursuit of his solo career. Having suff ered greatly without CAST: Rami Malek, Lucy Boynton, Joseph Mazzello the collaboration of Queen, Freddie manages to reunite with SYNOPSIS: Bohemian Rhapsody is a foot-stomping his bandmates just in time for Live Aid. While bravely facing celebration of Queen, their music and their extraordinary a recent Aids diagnosis, Freddie leads the band in one of the lead singer Freddie Mercury. Freddie defi ed stereotypes and greatest performances in the history of rock music. Queen shattered convention to become one of the most beloved cements a legacy that continues to inspire outsiders, dreamers Emergency 999 entertainers on the planet. The fi lm traces the meteoric rise and music lovers to this day. -

THE STOR Y Rarjer

THE STORy rArJER JAl\.LARY 1954 COLLECTOR No. 51 :: Vol. 3 6th Chri,tma' J,,ue, The Magner, i'o. 305, December 13, 191 "l From the Editor's NOTEBOOK HAVE Volume I, the first 26 name pictured in The Srory Paper issues, of the early Harms Collet!or No. 48, but the same I worth weekly paper for publisher, Rrett), a "large num· women, Forger-Me-Nor, which ber" of S11rpris�s, Plucks, Union was founded, I judge - for the Jacks, Marwls, and True Blues cover-pages are missing-late in were offereJ at one shilling for 1891. In No. 12, issued probably 48, post free to any address. Un in January 1892, there is mention like Forgec-Me-Nors in 1892, these of a letter from a member of papers must have been consi The Forget-Me-Not Club. ln the dered of little value in 1901. words of the Editress (as she What a difference today! calls herself): IF The Amalgamated Press A member of the Clul> tt•rites IO had issued our favorite papers inform me rha1 she inserted an ad in volumes, after the manner of vertisement in E x change and Mart, Chums in its earlier years, there offering Rider Haggard's "Jess" and would doubtless he a more Longfellow's poems for a copy of plentiful supply of Magnets and No. 1 of Forget-Me-Not, l>ut she Gems and the rest today. They did not receive an offer. This speaks did not even make any great 1'0lumes for 1he value of the earl: prndicc of providing covers for numbers of Forger-Me-Not. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

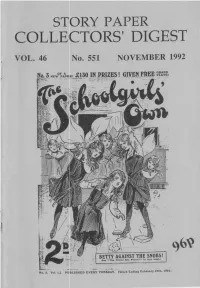

Colle1ctors' Digest

S PRY PAPER COLLE 1CTORS' DIGEST VOL. 46 No. 551 NOVEMBER 1992 BETTY AGAINST THE SNOBSI 8M u TIH Fri ... d atie ,..,,.,,d I'' II\ thi• IHllt.) - • ..a.... - No, 3, Vol . I ,) PU81. I SH£0 £VER Y TUESDAY, [Wnk End•nll f'~b,.,&ry l&th, 191 1, ONCORPORATING NORMAN SHAW) ROBIN OSBORNE, 84 BELVEDERE ROAD, LONDON SE 19 2HZ PHONE (BETWEEN 11 A.M . • 10 P.M.) 081-771 0541 Hi People, Varied selection of goodies on offer this month:- J. Many loose issues of TRIUMPH in basically very good condition (some staple rust) £3. each. 2. Round volume of TRIUMPH Jan-June 1938 £80. 3. GEM . bound volumes· all unifonn · 581. 620 (29/3 · 27.12.19) £110 621 . 646 (Jan· June 1920) £ 80 647 • 672 (July · Dec 1920) £ 80 4. 2 Volumes of MAGNET uniformly bound:- October 1938 - March 1939 £ 60 April 1939 - September 1939 £ 60 (or the pair for £100) 5. SWIFT - Vol. 7, Nos.1-53 & Vol. 5 Nos.l-52, both bound in single volumes £50 each. Many loose issues also available at £1 each - please enquire. 6. ROBIN - Vol.5, Nos. 1-52, bound in one volume £30. Many loose issues available of this title and other pre-school papers like PLA YHOUR, BIMBO, PIPPIN etc. at 50p each (substantial discounts for quantity), please enquire. 7. EAGLE - many issues of this popular paper. including some complete unbound volumes at the following rates: Vol. 1-10, £2 each, and Vol. 11 and subsequent at £1 each. Please advise requirements. 8. 2000 A.D. -

Viktoria Tolstoy & Viktoria Tolstoy & Jacob Karlzon Jacob

Viktoria Tolstoy & Jacob Karlzon A Moment Of Now ACT 97279727- ---2222 German Release Date: October 25, 2013 Though there are many beautiful singing voices in jazz ttoday,oday, Thanks to Tolstoy's father, who suggested Phil Collins' Viktoria Tolstoy is one of a kind. A great melodramatist of jazz "Against All Odds", the entire history of Genesis is who is also bipolar, she makes happiness sound fragile and represented, so to speak, with "Taking It All Too Hard" and threatened, and bitterness sweet and enchanting. She has Peter Gabriel's "Red Rain" also rebooted on the album. framed and perfected this art on a conceptual level since becoming an ACT artist in 2003, whether concentrating on Beyond global hits like these or Alanis Morissette's biggest material from Esbjörn Svensson – whose e.s.t. began to some success "Hand In My Pocket", the album also includes new extent as her accompanying trio – or, most recently, on Herbie discoveries like "Satisfied" from the almost-forgotten funk Hancock, classical originals, Swedish standards or repertoire virtuoso Lewis Taylor and "Deep River" from Norwegian jazz from Russia, the home of her ancestors. saxophonist Benedik Hofseth. Among the pieces, three were originally instrumentals; namely "Apres Un Reve" (based on Her latest album ""AA Moment Of NowNow"" is her most frank Faurè's "Apres Un Reve"), the Pat Metheny revamp "A recording yet – for one simple reason: "Jacob [Karlzon] and I Moment Of Now", and Karlzon's own composition "Scent Of are the concept this time," says Viktoria. Indeed it is an intimate Snow”. For these, Anna Alerstedt, the fantastic songwriter who album by the duo that focuses on their musical partnership. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

The Song of the Prairie Land 101 Pauline Johnson

CONTENTS PAGE A TOAST TO BEAUTY 17 PRELUDE 18 TIrE CRY OF THE SONG CHILDREN 20 A SONG TO CANADA 24 A POET STOOD FORLORN 27 SONG OF THE SNOWSHOE TRAMP 34 ADVERSITY. 40 WHOM SHALL MY HEART CONDEMN? • 42 FIRST SONG WITHOUT A NAME 49 THE WHIP-POOR-WILL 51 TRAPPER ONE AND TRAPPER Two; OR, THE GHOST OF UNGAVA. 57 REED SONGS 69 A SONG OF BROTHERHOOD 74 BARBARY 78 To THE UNCROWNED KINGS 80 I FEEL NOR UNDERSTAND 83 AT THE PIANO 85 THE WAKING THOUGHT 87 OTUS AND RISMEL (A BALLADE OF THE LONG SEA LANES) PAG! THE SONG OF THE PRAIRIE LAND 101 PAULINE JOHNSON. 107 THE HAUNT OF A LoST LoVE. 108 AT THE FORD • 109 THE ROSE AND THE WILDFLOWER 112 SECOND SONG WITHOUT A NAME 116 BRITISH COLUMBIA. 117 A SONG TO THE SINGERS. 119 ALONE 120 A SONG OF BETTER UNDERSTANDING 121 THE MONGREL. 126 WHIST-WHEE 132 THIRD SONG WITHOUT A NAME. 134 THE CONVICT MARCH. 135 MARY MAHONE. 137 SAINT ELIAS 141 AT BROOKSIDE MANOR. 144 SOMEWHERE, SOMETIME THE GLORY. 146 FRANCE • 148 GIFTS 149 By HOWE SOUND 150 PEACE 152 6 Prelude PRELUDE wo jugs upon a table stood; 1 am Caneo; T One ample of girth and sweet of cavern, And my skin is brown from the comrade sun. But a shapeless bit of homely wood And my heart is a cluster of grapes; each one That .you would scorn in the poorest tavern; I ip and ready to flow together The other traced and interlaced In the channel sweet of a purple song.