Memphis Rap in the 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Intellectual Property Into Their Own Hands

Taking Intellectual Property into Their Own Hands Amy Adler* & Jeanne C. Fromer** When we think about people seeking relief for infringement of their intellectual property rights under copyright and trademark laws, we typically assume they will operate within an overtly legal scheme. By contrast, creators of works that lie outside the subject matter, or at least outside the heartland, of intellectual property law often remedy copying of their works by asserting extralegal norms within their own tight-knit communities. In recent years, however, there has been a growing third category of relief-seekers: those taking intellectual property into their own hands, seeking relief outside the legal system for copying of works that fall well within the heartland of copyright or trademark laws, such as visual art, music, and fashion. They exercise intellectual property self-help in a constellation of ways. Most frequently, they use shaming, principally through social media or a similar platform, to call out perceived misappropriations. Other times, they reappropriate perceived misappropriations, therein generating new creative works. This Article identifies, illustrates, and analyzes this phenomenon using a diverse array of recent examples. Aggrieved creators can use self-help of the sorts we describe to accomplish much of what they hope to derive from successful infringement litigation: collect monetary damages, stop the appropriation, insist on attribution of their work, and correct potential misattributions of a misappropriation. We evaluate the benefits and demerits of intellectual property self-help as compared with more traditional intellectual property enforcement. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38KP7TR8W Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. -

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Luvin' a Certified Thug 3 by K.C. Mills

Luvin' A Certified Thug 3 By K.C. Mills READ ONLINE If searching for a ebook Luvin' A Certified Thug 3 by K.C. Mills in pdf form, in that case you come on to the correct site. We present full release of this book in DjVu, ePub, doc, txt, PDF formats. You may read Luvin' A Certified Thug 3 online by K.C. Mills or downloading. In addition to this book, on our site you may reading instructions and different artistic books online, or downloading theirs. We will to draw on your consideration what our website does not store the book itself, but we grant reference to site wherever you may downloading or reading online. So that if you have must to load pdf Luvin' A Certified Thug 3 by K.C. Mills, then you've come to correct site. We have Luvin' A Certified Thug 3 doc, PDF, txt, DjVu, ePub forms. We will be glad if you will be back again and again. [b7a.book] free download love, sex and staying warm: creating a Book] Free Download Loving Harder: Our Family's Odyssey through Adoption and Reactive .. [II5.Book] Free Download Luvin' A Certified Thug 3 By K.C. Mills. Stats: nicki minaj: the receipts - classic atrl to get the number you see. - Spotify and Youtube data were last updated January 15, 2016. Last edited by Truffle. 1/21/2016 at 1:16 PM. 5/11/2013, 3:06 AM Where my loyalties lie 2 by k.c. mills http://www.amazon.com/dp BWWM Romance: Crossing The Line 3: Interracial Romance / Wealthy Love Luvin' A Certified Thug 2, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B015MBRRJ8/ref= Luvin' a certified thug ebook: k.c. -

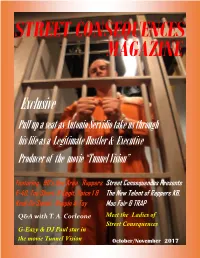

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

Underground Volume 16 for Da Summa Free Download DJ Paul Underground Volume 17 - for Da Summa

underground volume 16 for da summa free download DJ Paul Underground Volume 17 - For Da Summa. The newest DJ Paul album, "Underground Volume 17 - For Da Summa", was released on September 15th, 2017. The LP features guest appearances from artists such as Dave East, Yelawolf, Lil Jon, Lil Wyte, Riff Raff, and Lord Infamous (R.I.P.). Track list: 1. Fresh Out da Crazy House 2. Bitch Move (feat. Lil Jon, Lord Infamous & Layzie Bone) 3. Go Buck 4. Hell 2 da Naw 5. No High Enough (feat. Lil Wyte) 6. Headshot Hair Do 7. Tryin' to Get It (Album Mix) [feat. Dave East & Jon Connor] 8. Spend Sum (Album Mix) [feat. Weirdo King] 9. Me Too (Skit) [feat. Computer Russell Resthaven] 10. Me Too 11. Crazy Off da Bud (Remix) [feat. Lord Infamous] 12. Poe Up Wetty (feat. Lil Wyte) 13. Litty Up (Album Mix) [feat. Yelawolf] 14. No Sex, No Cryin' (Skit) [feat. Joe Judah] 15. No Sex, No Cryin' 16. Real Fake (feat. Riff Raff) 17. Ain't Gone Love It (Album Mix) [feat. Weirdo King] 18. Side Figga 19. My Shadow (feat. Seed of 6ix) 20. Outro. Days to release. Add News & Media Report Leak or stream. Album details. Hype: 0 Artist: DJ Paul Album: Underground Volume 17 - For Da Summa Official Release: Sep 15, 2017 Genre: HipHop, Rap. Visit Has it Leaked but for movies, Where You Watch. Slaughter To Prevail . Iron Maiden : Senjutsu Dream Theater : A View. The Killers : Pressure. Kanye West : DONDA Between The Buried And. Lorna Shore : …And I Re. Lorde : Solar Power Deafheaven : Infinite G. -

PDF (1.41 Mib)

B2 ARCADE WWW.THEHULLABALOO.COM THREE 6 MAFIA, 15 YEARS· LATER: .. :r '» THE INFLUENCE OF MYSTIC STYLEZ f t' BY ZACH YANOWITZ rel couldn't tell you half about this antichrist/Look into my eyes ASSISTANT ARCADE EDITOR tell me what you see/1he demonic man about s 」 。 イ ・ 」 イ ッ キ ゥ ウ ュ セ The J vast majority of Mystic Stylez is far too offensive for publication: • i.i There's something intrinsically off about a white boy from the These guys (and singular gal) were not messing around. Massachusetts suburbs reviewing what might be the hardest rap Despite the shocking lyrics and underground production, Tri- h'lbum of all time, but I'm going to give it a shot ple-6 made the most of its low budget 'lhe eerie minimalist beats _.. ,: The members of 'lhree 6 Mafia had a long journey before they sample church bells and graveyard ・ ヲ ヲ ・ 」 セ N producing sounds that '&gan winning Academy Awards and hanging out with Andy could be the score to a horror movie. Chopped-and-screwed vocals Milonakis. Brothers DJ Paul and Juicy J formed the group, which and minor piano chords emphasize the rising tension throughout %iginally included Lord Infamous (Da Scarecrow), Gangsta Boo, the album that settles with laidback '90s hoodrat tunes such as 't<oopsta Knicca and Crunchy Black Since then, they've lost all "Da Summa," a song about the simple yet still explicit pleasures of 1nembers but Paul and J - and most of their street creel, too - Memphis life. Call-and-response choruses and the high-cadence 'lfiut their early music is a very· different creature. -

Three 6 Mafia, We 'Bout to Ride

Three 6 Mafia, We 'Bout To Ride [DJ Paul: talking] yeah nigga the mother fuckin two time two time motherfuckin champions in this bitch I got another motherfuckin gold plaque on the wall now nigga now tell me what you think about that look me in my eyes and tell me nigga bitch bitch bitch bitch hoe hoe hoe nigga [Juicy J] (background mixed through various parts of whole song) drop em in the trunk lock em in trunk real fast you'll be flying [Crunchy Black] we bout to ride on these fools cock these nines on these fools [x2] [DJ Paul] like thisssssssssss now in my city its so real in my city its so fake got some niggas that's gone play got some niggas that gone hate got some niggas that's gone dis the treal niggas on the tape but them the ones who want the streets so they start to evaporate that's why them niggas ain't around no more cause them niggas could sell no more without the Hypnotize or the Prophet nigga you is no more got plaques up on my walls got twenties on my cars keep coming like you coming and I'm gonna show you I ain't fucked up bout no charge nigga [Juicy J] can you niggas feel my pain catch me standing in the rain holding on a rusty 2 bout to act a fuckin fool is the 6 the devil though make you wanna powder your nose have you smoking hydro weed satisfaction guaranteed bucking wild and throwing signs knowing these niggas done loss they minds blame it on Coriddy and Ooh when we cock them thangs and shoot thinking somebody had seen my face now I'm gonna catch a murder case just gonna beat him round for round and leave him in -

Three 6 Mafia, Flashes

Three 6 Mafia, Flashes [Chorus x3] I keep on havin' these flashes Murder by the masses Sick off human ashes Hatas passion [dj paul] We motherfuckin' whole mothas Glock huggas Rob till we rob each other, facked on any motherfucka nigga .40 cal's got me dangery Like jj fad icredible hoe don't make me anga-ry We prophet posse got you in the cross We done gotcha In the motherfuckin' scope We done shot cha We get more wilder than a chicken with his head cut off Three 6 mafia hypnotizin' don't make me set it off [gangsta boo] Screamin' notha fuckin' murder, murder, murder on my mind Gettin' wild with these hella fied rhymes on ya mind Never the on be mistaken Never the one takin' a loss I always be the fuckin' one who to be the damn doubt Watcha say, nigga what You wanna get up in my shit Shit gonna get your ass in trouble Shit gonna get your head split Stay focused stay rollin' when i'm ridin' dirty nigga Gettin' twisted off some nigga Dedicated to you killa [Chorus x3] [juicy j] Guess who was scared Niggas stalkin' in the memphis streets The triple 6 them mafia niggas you don't wanna meet Creep up on your ass and let the barrel sweep Sweep and let the blast take you from off your feet And to your family and your friends i know them hoes will miss you You should have warned them that the three 6 mafia out to get cha Would you walk to his house with a pistol Could you let the heat go like you shouldn't have missed him [koopsta knicca] It's the blue lights in the night When i go for ridin' I'm seein' headlights on the right creepin' up from behind Ran that trick hit the d Fuckety-fuck with the hennessy Leavin' that third, need reserve Droppin' on the curve to by to my (??) See by a chance that he may touch me it's a hint that he gonna miss Cause i will take some plastic man and rip this skin up off this Motherfuckin' piece So now he diss me No one can play hey, now tell me wha'ts next Come here play he say (??) [Chorus...till fade] Three 6 Mafia - Flashes w Teksciory.pl. -

Three 6 Mafia, 44 Killerz

Three 6 Mafia, 44 Killerz (dj paul and juicy j) I'm bout to blow them boys ass off (whatcha niggas wanna do? ) I'm bout to blow them boys ass off (talkin all that f**kin shit) I'm bout to blow them boys ass off (coward ass bitches) I'm bout to blow them boys ass off (whatcha niggas wanna do? ) I'm bout to blow them boys ass off (talkin all that f**king shit) I'm bout to blow them boys ass off (fighting niggas over a bitch) I'm bout to blow them boys ass off (f**k you motherf**kin hoes) I'm bout to blow them boys ass off (juicy j) To you haters I'm the predator Set em up, wet em up When I'm in the hood, I'm like a drug-dealer regular Coke poppin, bird shoppin, droppin don'tcha step ta tha Triple six, guns click, bitch we the murderers (crunchy black) Triple six is the clique, why y'all niggas keep hatin me Y'all gone make a nigga posse up and come and getcha bitch Grab that nigga by his throat, if he hollas, let em go I ain't gon' let that nigga go, i'ma hit it at em wit da fourty-four (lord infamous) I'ma sic' em, heat em, leave em bleedin, fill em fulla millimeter Bitch ass nigga, torture treat em, creature feature, coke and weed Soze, two-l o y d, sippin ounces of that liter Ask me if I worship satan, i'ma send yo ass ta see em (dj paul) Now tell me how you boys talk wit all that shit in yo mouth And how the hell you down ta key that open doors for tha mid-south? I put half of you haters on, make half of you haters groan Left half of you haters alone And watched you die all on your own and feel for ya (dj paul and juicy j) I'm bout -

Petey Pablo Is Crazy

Call your cable provider to request MTV Jams Comcast Cable 1-800-COMCAST www.comcast.com Atlanta, GA Comcast ch. 167 Augusta, GA Comcast ch. 142 Charleston, SC Comcast ch. 167 Chattanooga, TN Comcast ch. 142 Ft. Laud., FL Comcast ch. 142 Hattiesburg, MS Comcast ch. 142 Houston, TX Comcast ch. 134 Jacksonville, FL Comcast ch. 470 Knoxville, TN Comcast ch. 142 Little Rock, AR Comcast ch. 142 Miami, FL Comcast ch. 142 Mobile, AL Comcast ch. 142 Montgomery, AL Comcast ch. 304 Naples, FL Comcast ch. 142 Nashville, TN Comcast ch. 142 Panama City, FL Comcast ch. 142 Richmond, VA Comcast ch. 142 Savannah, GA Comcast ch. 142 Tallahassee, FL Comcast ch. 142 Charter Digital 1-800-GETCHARTER www.charter.com Birmingham, AL Charter ch. 304 Dallas, TX Charter ch. 227 Greenville, SC Charter ch. 204 Ft. Worth, TX Charter ch. 229 Spartanburg, SC Charter ch. 204 Grande Communications www.grandecom.com Austin, TX Grande ch. 185 PUBLISHERS: Julia Beverly (JB) Chino EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Julia Beverly (JB) MUSIC REVIEWS: ADG, Wally Sparks CONTRIBUTORS: Bogan, Cynthia Coutard, Dain Bur- roughs, Darnella Dunham, Felisha Foxx, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Katerina Perez, Keith Kennedy, K.G. Mosley, King Yella, Lisa Cole- man, Malik “Copafeel” Abdul, Marcus DeWayne, Matt Sonzala, Maurice G. Garland, Natalia Gomez, Ray Tamarra, Rayfield Warren, Rohit Loomba, Spiff, Swift SALES CONSULTANT: Che’ Johnson (Gotta Boogie) LEGAL AFFAIRS: Kyle P. King, P.A. (King Law Firm) STREET REPS: Al-My-T, B-Lord, Bill Rickett, Black, Bull, Cedric Walker, Chill, Chilly C, Control- ler, Dap, Delight, Dereck Washington, Derek Jurand, Dwayne Barnum, Dr. -

The Beautiful Struggle: an Analysis of Hip-Hop Icons, Archetypes and Aesthetics

THE BEAUTIFUL STRUGGLE: AN ANALYSIS OF HIP-HOP ICONS, ARCHETYPES AND AESTHETICS ________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ________________________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________________ by William Edward Boone August, 2008 ii © William Edward Boone 2008 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The Beautiful Struggle: an Analysis of Hip-Hop Icons, Archetypes and Aesthetics William Edward Boone Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Nathaniel Norment, Ph.D. Hip hop reached its thirty-fifth year of existence in 2008. Hip hop has indeed evolved into a global phenomenon. This dissertation is grounded in Afro-modern, Afrocentric and African-centered theory and utilizes textual and content analysis. This dissertation offers a panoramic view of pre-hip hop era and hip hop era icons, iconology, archetypes and aesthetics and teases out their influence on hip hop aesthetics. I identify specific figures, movements and events within the context of African American and American folk and popular culture traditions and link them to developments within hip hop culture, iconography, and aesthetics. Chapter 1 provides an introduction, which includes a definition of terms, statement of the problem and literature review. It also offers a perfunctory discussion of hip hop -

Download File

Get Crunk! The Performative Resistance of Atlanta Hip-Hop Party Music Kevin C. Holt Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 ©2018 Kevin C. Holt All rights reserved ABSTRACT Get Crunk! The Performative Resistance of Atlanta Hip-Hop Party Music Kevin C. Holt This dissertation offers an aesthetic and historical overview of crunk, a hip- hop subgenre that took form in Atlanta, Georgia during the late 1990s. Get Crunk! is an ethnography that draws heavily on methodologies from African-American studies, musicological analysis, and performance studies in order to discuss crunk as a performed response to the policing of black youth in public space in the 1990s. Crunk is a subgenre of hip-hop that emanated from party circuits in the American southeast during the 1990s, characterized by the prevalence of repeating chanted phrases, harmonically sparse beats, and moderate tempi. The music is often accompanied by images that convey psychic pain, i.e. contortions of the body and face, and a moshing dance style in which participants thrash against one another in spontaneously formed epicenters while chanting along with the music. Crunk’s ascension to prominence coincided with a moment in Atlanta’s history during which inhabitants worked diligently to redefine Atlanta for various political purposes. Some hoped to recast the city as a cosmopolitan tourist destination for the approaching new millennium, while others sought to recreate the city as a beacon of Southern gentility, an articulation of the city’s mythologized pre-Civil War existence; both of these positions impacted Atlanta’s growing hip-hop community, which had the twins goals of drawing in black youth tourism and creating and marketing an easily identifiable Southern style of hip-hop for mainstream consumption; the result was crunk.